Paradise lost? Falling foreign investments in China

The People’s Bank of China has reported that the third quarter of 2023 saw an outflow of foreign direct investment (FDI); this is the first time this has happened in at least 25 years. However, these data do not fully reflect real economic processes. Foreign companies have long appreciated China due to the appealing business conditions on offer. However, the investment climate in this country has been deteriorating in recent years due to Beijing’s domestic policy and its escalating rivalry with Washington. The People's Republic of China led by Xi Jinping has given special priority to economic security, introducing a number of regulations that have adversely affected foreign investors. However, business circles, encouraged by the US and EU authorities to de-risk, have responded to the mounting challenges in different ways. Some companies are cutting investments to reduce the risks associated with their strong ties to the Chinese market, others are increasing expenditure to strengthen and isolate their Chinese operations. Getting the proportions right is a challenge, but a complex mosaic of data paints a picture of a structural decline in FDI in China. FDI indicators may improve in the coming years, but structural processes motivated by economic calculation and political pressure will probably lead to further restrictions on investments in China as part of a gradual, comprehensive reduction of the dependence of foreign business on the Chinese industrial base.

China became one of the world’s largest recipients of foreign direct investment (FDI)[1] during the ‘reform and opening up’ period that began in the late 1970s. Inclusion in global supply chains was the key to China’s immense economic success in recent decades. The inflow of capital not only created millions of jobs but also contributed to the transfer of knowledge, skills and technologies that formed the foundation of development. However, foreign business has gradually become ever more dependent on China as a key production site and source of supplies, and in later years also as an important outlet.

As relations between Washington and Beijing became extremely strained, the West realised that its economic dependence on China was a serious problem, which has both economic and political implications. US President Donald Trump started calling for a so-called decoupling, which meant cutting off economic ties with China. This met with strong resistance from the business community, which argued that this solution would be at best unprofitable, and at worst impossible. In the following years, this term was replaced (also in the statements from European Union leaders) with the term de-risking, which means the more precise identification and restriction of potentially dangerous dependencies.[2]

Analogous, though much more advanced, processes that are underway in China have also gained momentum. The overriding goal of Beijing’s economic policy has[3] and therefore, indirectly, also by its representatives: companies and citizens who can be used in the political game.

In the past, political risk was compensated by bright economic prospects for foreign business, but now this ratio is becoming less favourable to investors. The increasing risk in China – as a result of both the way the international situation is developing and the moves made by Beijing itself – has a clear impact on foreign businesses, and this is reflected in investment decisions.

The mosaic of data

While the quality and reliability of Chinese statistics raise serious doubts, all sources suggest there has been a decline in Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) inflow into China recently, although there is a clear divergence in terms of the scale and assessment of the onset of this process. Similar trends are also reflected in surveys conducted by American and European chambers of commerce among foreign enterprises operating in the People’s Republic of China. Direct statements from companies and media reports echo this trend. All of these confirm that an increasing percentage of firms are seeking to reduce their dependence on China, including scaling back new investments in the country and increasing expenditures in competitive locations, such as Southeast Asian countries. However, this is compounded by several other processes that obscure the statistical picture, such as capital flight or strictly financial flows, which in the Chinese context are often disguised as Foreign Direct Investments.

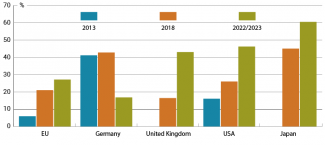

Chart 1. Share of firms that are not planning to increase investment in China within two years

Source: A. Kratz, C. Boullenois, ‘Irrational Expectations: Long-Term Challenges of Diversification Away from China’, Rhodium Group, 13 September 2023, rhg.com.

In recent months, particular attention has been drawn to data from the People's Bank of China, which reported that in the third quarter of last year, for the first time in at least 25 years, there was an outflow of Foreign Direct Investment (FDI), amounting to 84.6 billion yuan. However, this result sharply contrasted with statistics published by the Ministry of Commerce of the People’s Republic of China, indicating that ‘utilised FDI’ during the same period amounted to 216 billion yuan, compared to 280 billion yuan in the corresponding period of 2022.

This discrepancy can be easily explained: central bank data includes not only new investments but also divestments (such as the selling of shares), reinvested profits[4] and financial flows between companies within the same capital group.[5] If both sets of information are considered reliable, it would lead to the conclusion that foreign companies which have previously invested in China are withdrawing funds from the country (selling assets or choosing not to reinvest profits), while new investors are deciding to enter the Chinese market. This situation has been ongoing for almost two years, primarily due to higher interest rates in the USA. Investors are therefore transferring idle funds from their Chinese companies to their other companies operating in other countries. They consider placing them in higher-yielding investments outside China more attractive than increasing capital commitment in the People’s Republic of China, especially in light of the worsening prospects of the Chinese economy.

While international reactions to the latest central bank data may appear to be overly alarmist, the statistics provided by the Ministry of Commerce likely underestimate the extent of the slowdown in Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) inflow into China. Official readings have consistently shown an almost uninterrupted, gradual increase in the ‘utilisation’ of FDI for years. Given the nature of the investment process and economic cycles, it is unlikely that such linear growth would be observed and it suggests a distortion of statistics. Only in 2023 do they reveal a slight decrease: in the first three quarters, the ‘utilisation’ of FDI was over 8% lower than in the same period of the previous year. Like other macroeconomic indicators published by the Chinese government, this one is intended to serve propaganda purposes rather than to provide reliable information. Furthermore, data on the size of investments in a specific year lags behind the change in investor sentiment: the inflow is not recorded when the decision to start the investment process is made, but often many months later, when the funds are transferred.

It is even more difficult to analyse the data in a reliable manner, given the fact that both the central bank’s information and the Commerce Ministry’s data on FDI include not only investments by foreign entities but also those originating from China. Chinese companies invest funds at home through offshore financial centres, such as Hong Kong, the Virgin Islands or the Cayman Islands (this practice is known as ‘round-tripping’), to take advantage of the incentives offered to ‘foreign’ investors and to conceal ownership titles. The noticeable outflow, as indicated in the data from the People’s Bank of China, could therefore be further proof suggesting capital flight and an intensification of attempts by Chinese citizens to withdraw funds from the country.

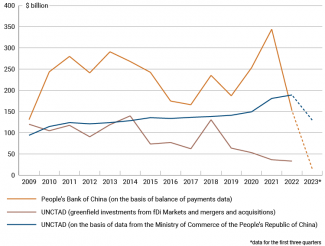

Macroeconomic data published by the Chinese government indicate a shift in the trend and a reduction in FDI inflow in 2022 and 2023. However, economic logic suggests that this process began earlier: due to the escalation of the conflict between Beijing and Washington during the Trump presidency or following the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic which disrupted business operations, for example, as a result of restrictions on travel to and from China. The likelihood of this scenario is supported by statistics published by credible foreign entities, such as an annex to the World Investment Report by UNCTAD.[6] They reveal a gradual decrease in FDI inflow since 2015, with the exception of 2018 (see chart 2).

Chart 2. FDI inflow to China in 2009−2023

Source: author’s own calculations based on data from the People’s Bank of China, United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) and the Ministry of Commerce of the People’s Republic of China.

Paradise lost

This means that the lower interest rates in China compared to developed economies were the main reason behind the unusual outflow of FDI seen in the central bank’s data for IIIQ 2023. Additionally, investments are currently declining due to the suspension of associated processes in the face of the coronavirus pandemic and Beijing’s ‘zero COVID’ strategy. However, within the mosaic of macroeconomic data and the moves made by individual companies, it is also possible to perceive more significant long-term processes, primarily stemming from business considerations: attempts at a diversification of operations and reducing dependence on China.

In recent years, ensuring business security has become increasingly prominent, overshadowing the traditionally dominant focus on cost reduction in globalisation processes. The COVID-19 pandemic and the West’s response to Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine clearly demonstrated the importance of supply chain diversification and resilience. This conviction is reinforced by growing concerns about the consequences of escalating conflicts in the Taiwan Strait and the rivalry between Washington and Beijing. According to the US-China Business Council, one in four American companies surveyed cited “rising costs or uncertainties resulting from tensions between the USA and China” as a reason for reducing or suspending their investments in China in 2022.

Moreover, there has been a shift in the balance of the potential costs and benefits associated with doing business in China. The Chinese economy is experiencing a structural slowdown, and the competition for market share is escalating. Xi Jinping has redefined the priorities of the Chinese government, with the primary objective being to ensure comprehensive national security, including economic security. Concurrently, the West, in particular the United States, is perceived as the primary threat. This perception is not only evident in the rhetoric but also in concrete actions that adversely affect the investment climate in China. In the pursuit of national security, Beijing has implemented measures such as restricting the transfer of data abroad and restricting prospective investors’ access to information, for example, by launching investigations into the operation of foreign consulting firms,[7] restricting access to corporate and macroeconomic databases and censoring negative economic analyses. Formally, government agencies have been given more extensive access to internal company data. Additionally, increasing numbers of government agencies and state-owned enterprises are prohibiting employees from using iPhones and other foreign electronic devices at work. The government has also restricted access for Tesla vehicles to specific areas, particularly when Xi Jinping is present there.

From a business viewpoint, the expansive scope and ambiguity of regulations are the source of the greatest challenges.[8] Coupled with the widespread practice of arbitrary law enforcement and using economic dependencies for political purposes, this adds to the uncertainty and risk associated with doing business in China, especially amidst the escalating rivalry between Washington and Beijing. Investor sentiment is further impacted by unexpected reports of investigations initiated against a key partner of Apple, the Taiwanese company Foxconn,[9] as well as the arrests and disappearances of high-profile businessmen. Additional factors which contribute to a challenging environment include: travel bans for individuals loosely associated with those suspected of committing crimes, anti-spying campaigns encouraging citizens to report any ‘suspicious’ behaviour from foreigners, the establishment of party cells within private companies, growing nationalism, the closure of the accounts of economic commentators on social media, and increased media activity by the Ministry of Public Security. Given all this, it is increasingly challenging to find competent personnel willing to work for foreign companies operating in China; and this concerns both foreign and local employees.

Foreign businesses have not been the primary target of the Chinese government’s several major campaigns in recent years, including the one targeted against the consumer technology sector, the anti-corruption campaign or the one linked with the ‘zero COVID’ strategy. However, they have strongly felt the effects and have become aware of the growing, arbitrary and often unpredictable interference of the Communist Party of China in the operations of the private sector, which is expected to become more committed to achieving the goals set by Beijing rather than focus on profitability. A record-high percentage (64%) of respondents in last year’s survey by the European Chamber of Commerce in China admitted that doing business in the country had become more challenging in the past year.

Due to the Chinese government’s financial problems triggered by the real estate market crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic, potential investors can no longer count on access to such favourable incentives. In the past, they would usually be offered generous subsidies, and inexpensive land and tax exemptions. Furthermore, labour costs in China have obviously risen dramatically in recent decades.

In China for China

Despite these factors, not all potential investors are deterred. China still has much to offer them: a large consumer market, well-established networks of suppliers and subcontractors, a significant pool of well-trained, determined, flexible and cost-effective workers, world-class infrastructure, relatively low energy prices, a weaker currency, conditions facilitating a dynamic production process, relatively low tax burdens, lax accounting standards and a blind eye turned to workers being abused by their employers.

Given the increasing market competition, a shift in Beijing’s approach to the economy and business and the escalating rivalry between China and the West, new foreign investments now have a more defensive character. They are primarily aimed at safeguarding existing investments, so as to protect not only financial capital but also the human resources: knowledge, organisational know-how, network connections, etc. Companies are making efforts to fortify their presence in China and to separate local operations from the broader scope of their global activities, implementing an ‘In China, for China’ strategy. The objective is to manufacture goods primarily for the Chinese market and thus protect themselves against the potential loss of access to this market or increased costs due to a possible implementation of protectionist measures by Beijing, Washington or Brussels. This strategy is primarily adopted by large companies with a relatively strong position in the Chinese market.[10]

Among them, German automotive giants[11] have adopted a unique strategy. The CEO of Mercedes-Benz has stated that the company is undergoing a de-risking process by increasing, not decreasing, its presence in China. Volkswagen announced investments in China totalling nearly $5 billion last year. Car manufacturers argue that this is part of their strategy to maintain competitiveness in the face of Chinese expansion in the electromobility sector.[12] If they focus on development in the Chinese market, they will be able to catch up with their competitors and reduce the negative impact of potential disruptions (such as punitive tariffs or other sanctions) in the international flow of components and finished products, especially if their attempts to isolate the company’s operations in China from the rest of its business prove successful. However, this strategy poses the risk that the company’s Chinese branch may be taken over by Chinese entities in the event of a clear escalation of political conflict between Beijing and Berlin, for example, due to an attack on Taiwan.[13]

Local authorities are making efforts to support this trend. Foreign investments are currently very important at the local level due to the poor condition of public finances and low economic growth.[14] In turn, the central government definitely prioritises security, even though it must contend with the consequences of capital outflow[15] and the negative perception of the state and economic prospects, and therefore also of the way the Communist Party governs the country. Beijing continues to seek investments that guarantee the inflow of knowledge and technology, particularly in advanced production and the biomedicine sectors, which are essential for reducing China’s dependence on foreign supplies. It also strives to gain additional allies who would support its interests in Washington, including representatives of the financial sector who have political influence in the US and who account for a significant share of the American economy. In August, the Chinese government announced a 24-point plan aimed at attracting investments and improving the business environment, and continued reiterating its commitment to addressing the needs of entrepreneurs in the following months. In response to a wave of criticism from foreign investors in September, it presented a project to ease regulations concerning the international flow of data. Chinese senior officials, including Xi Jinping, regularly meet with business representatives, such as Apple’s CEO Tim Cook and Microsoft’s founder Bill Gates.

Prospects

China plays a central role in global supply chains, and this is impossible to change in the short run. No other country provides investors with such conditions for expanding production: access to a workforce, infrastructure, supplier networks and such a large market. Therefore, businesspeople are not underestimating the warning signals and are more often tending to choose the ‘China+1’ strategy: companies continue their operations in China while also working to set up independent supply chains in other countries for added diversification. However, this is a costly and time-consuming process.

Transferring specific components of the value chain to other countries does not always lead to a substantial reduction in dependence on China. Even with new factories outside China, companies will still have to rely on deliveries of materials or components from this country. However, this scenario is expected to change gradually in coming years. Countries attracting significant investments will emulate China by internalising a growing portion of supply chains, and thus enhancing their role in the creation of added value.

Growing political pressure and increased awareness of the costs of insufficient diversification will discourage investors from investing funds in China. While this may not be the main economic challenge for Beijing, it may still have adverse political consequences. It will limit the Chinese government’s ability to exert influence on other countries by applying pressure on business circles. China is no longer as dependent on the influx of capital and knowledge from abroad as during the ‘reform and opening-up’ period, when they played a fundamental role in driving the growth and development of what was an underdeveloped state. In its pursuit to enhance national security, Beijing will intensify efforts to attract investments that guarantee the transfer of modern technologies, since China still does not have them and has to rely on the transfer of them from abroad. The governments of developed countries will increasingly counteract this, both through prohibitions and incentives to develop operations in the home country or in a ‘friendly’ one.[16]

Beijing will continue its attempts to play Western companies against Western governments, while also declaring its support and openness to foreign investors as well as strong opposition to protectionist practices. However, business representatives should take these assurances and promises with a grain of salt, and be aware of the risks associated with the policy aimed at enhancing security amid the escalating rivalry between China and the West.

[1] Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) is defined as the total or partial takeover of ownership of an existing business entity abroad or the creation of a new one to conduct business there. The IMF and the OECD believe that an investment may be considered direct if, as a result, the investor’s share in the company will be no less than 10% of the voting power in the business.

[2] See P. Uznańska, M. Kalwasiński, ‘Technologiczny de-risking. Europejska lista technologii krytycznych’, OSW, 9 October 2023, osw.waw.pl.

[3] See M. Bogusz, ‘China after the 20th CCP Congress: a new stage in Xi Jinping's revolution’, OSW Commentary, no. 475, 7 November 2022, osw.waw.pl.

[4] The People’s Bank of China, unlike other key central banks, does not specify the level of profits reinvested by foreign investors in the balance of payments. These profits may decrease not only due to the transfer of earnings to the foreign parent company but also as a result of reduced income. In the first three quarters of 2023, the profits of foreign-invested companies in China declined by over 10% y/y.

[5] This discrepancy is also partly due to the different methodologies used – see N.R. Lardy, ‘Foreign direct investment is exiting China, new data show’, Peterson Institute for International Economics, 17 November 2023, piie.com.

[6] fDi Markets publishes data on greenfield investments (building businesses from scratch in different countries). Several organisations aggregate data on mergers and acquisitions, which are not directly comparable with Chinese data. fDi Markets relies on announcements when investments are declared, and they are typically implemented over a period of several years and are subject to change. It does not take into account subsequent stages of business development, including reinvesting profits. As with mergers and acquisitions, the value of transactions in greenfield investments is sometimes concealed, not only for commercial reasons but also, in recent years, for political ones (businesses are unwilling to expose themselves to either Washington or Beijing). As a result, providers rely on estimates of the investment scale.

[7] They play a fundamental role in the investment process as they provide essential risk analyses, compliance assessments and evaluations of market potential. In recent months, law enforcement agencies have raided the Beijing office of Mintz Group, arresting several of its employees, and the company was fined $1.5 million for illegally obtaining data. Another company under investigation by the Chinese government is Capvision, which has been alleged to have aided in espionage.

[8] The counterintelligence law of the People’s Republic of China includes terms such as “acts harmful to the national interests of China” and “data that may pose a threat to national security”.

[9] The Chinese authorities initiated several investigations into Foxconn’s operations when candidates in the presidential race in Taiwan were presented. Terry Gou, the founder of Foxconn, was mentioned as a potential contender. It was believed that his participation could divert votes from the Kuomintang (KMT) party’s candidate, who was favoured by Beijing. The launch of the investigation precisely at this moment was interpreted as an attempt to pressure Gou to withdraw from the electoral race, which he eventually did.

[10] The negative changes have a stronger impact on smaller organisations, which are more inclined to withdraw from the country.

[11] According to calculations by the Institut der deutschen Wirtschaft, German companies invested over €10 billion in the Chinese market in the first half of 2023. This is the second-highest result in history (the highest was achieved in 2022). China’s share in German Foreign Direct Investments increased to 16.4% as compared to 11.6% in 2022 and 5.1% in 2019.

[12] See K. Popławski, ‘Can the global battle for electromobility pose a threat to Central Europe?’, OSW Commentary, no. 504, 30 March 2023, osw.waw.pl.

[13] See M. Bogusz, The silicon shield. Taiwan amid the superpowers’ rivalry, OSW, Warsaw 2023, osw.waw.pl.

[14] See M. Kalwasiński, ‘Disappointing post-COVID-19 recovery. China on the path of protracted slowdown’, OSW Commentary, no. 522, 7 July 2023, osw.waw.pl.

[15] According to Goldman Sachs analysts’ estimates, capital outflow in September stood at $75 billion, and so was the highest since 2016.

[16] See P. Uznańska, M. Kalwasiński, ‘Technologiczny de-risking. Europejska lista technologii krytycznych’, op. cit.