A lot of effort, not many results. Latvia’s belated de-Sovietisation

The Russian invasion of Ukraine marked the beginning of a new chapter in the Latvian state’s policy towards the Russian-speaking minority which accounts for around a third of the country’s population. The shock caused by the Russia’s attack and the crimes it perpetrated drove Riga to decide to reorganise Latvian society and to eliminate all things Russian alongside the remnants of the colonial Soviet past. The government’s long-term goal is to put an end to the disputes which Moscow constantly stokes and which have been dividing the public for decades. The main instrument of these activities involves rapid legislative amendments regarding issues such as education, culture, migration policy and citizenship legislation.

However, due to the fact that the new laws were frequently prepared under emotional and time-related pressure, their implementation has not proceeded as intended. Some remain partly defunct due to their insufficient adaptation to social realities, while others have lost their edge due to subsequent amendments. Problems with the implementation of the enacted laws indicate that former disputes over language, education and memory policy have not only remained unresolved, but have actually paved the way for the increased radicalisation and alienation of extremist groups.

Two different worlds

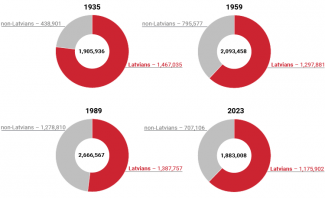

Latvian society’s division into the Latvian-speaking part and the Russian-speaking one has always been one of the key challenges for the state. This unique dualism is a legacy of the colonisation of Latvian lands during the Soviet era. Back then, Moscow pursued a policy which involved settling Russians and Russified representatives of other nationalities hailing from various regions of the Soviet empire in what is now Latvia. As a consequence, in the final years of the Soviet Union, ethnic Latvians accounted for just over half (52%) of the population of the Latvian Soviet Socialist Republic.

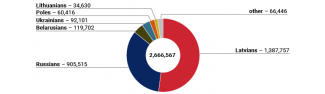

Chart 1. Latvia’s ethnic composition according to the 1989 census

Source: figures compiled by the Latvian statistical office, data.stat.gov.lv.

Over the last three decades, the proportion on ethnic Latvians in Latvia’s society has risen to 62%. Compared with the Soviet era and the 1990s, the importance of Latvia’s culture, language and ethnos has also risen. The number of descendants of ethnic Russians, Belarusians and Ukrainians, collectively referred to as the Russian-speaking population, has declined significantly and their social status has also changed. At present, in political, symbolic and even economic terms,[1] it is much less highly regarded than back in the Soviet era, when in many aspects these individuals were more privileged than ethnic Latvians.

Source: figures compiled by the Latvian statistical office, stat.gov.lv.

Although the Russian-speaking population is scattered across Latvia, its biggest clusters are located in the eastern part of the country (around 54% of the residents of Latgale are members of national minorities) and in Riga (around 53%). Some representatives of the Russian-speaking minority still do not hold Latvian citizenship and are referred to as so-called ‘non-citizens’ (around 10% of the population) or are citizens of a third country (around 3%, mainly Russia or another state which emerged following the collapse of the USSR). Non-citizens do not have voting rights and are not allowed to apply for specific positions in the public administration.

Internal divisions, especially as regards the politics of memory, education, language and symbols displayed in the public space, usually ran along the lines of ethnicity. For many years, the non-Latvian electorate was represented by the Social Democratic Party ‘Harmony’ (Sociāldemokrātiskā partija ‘Saskaņa’, SDPS). From 2011 until autumn 2022, this party (which operated under the name ‘Harmony Centre’ until 2014) came first in every parliamentary election, but was never able to join the government.[2] ‘Harmony’, which presents itself as a centre-left party and is viewed by the majority of the centre-right parties as a pro-Russian grouping, was successfully excised from the rest of the political scene by a unique political ‘cordon sanitaire’ for a decade. Alongside this, its strong position, for example in the local governments, enabled it to act as a brake on some socio-political processes which the government endorsed. For example, it pursued a separate policy regarding the use of symbols in the public space and organised its own celebrations of historical anniversaries.

Alongside this, another strongly pro-Russian party has operated on the margins of Latvia’s political life: the Latvian Russian Union (Latvijas Krievu savienība, LKS), a long-term extra-parliamentary grouping. The For Stability! (Stabilitātei!, S!) party established in 2021 has been a new political organisation bringing together a section of radical Russian-speaking voters. It was founded by a group of dissenting members of ‘Harmony’ who had left their party. At present, its level of support is around 9% depending on the specific poll.

The waves of de-Sovietisation prior to 2022

Since 1991, when Latvia regained independence, there have been several waves of de-Sovietisation. The biggest wave happened in the early 1990s and involved the removal of the relics of the Communist system which Latvians viewed as oppressive, of which there were many at that time. The most radical changes concerned monuments and the rules of granting Latvian citizenship. The 1990s saw the removal of statues of Lenin,[3] as well as monuments to Soviet soldiers and Latvian Communists, from the public space. The oldest ‘monuments of architecture’ dating from the Stalinist era were demolished because they were in danger of collapse.[4] Further radical moves were blocked by the agreement Latvia signed with the Russian Federation in 1994.[5] Riga’s priorities at that time were to avoid exacerbating its relations with the Kremlin and to have the Russian troops withdrawn by autumn 1994, while its main goals included a quick integration with the EU and NATO. Moscow repeatedly attempted to influence Latvia’s minority policy by organising information campaigns, including ones targeted at the West.[6]

The situation stabilised to some degree, when a law on citizenship was enacted in 1994. In its repeatedly amended wording it continues to regulate the life of Latvian society. On the basis of this law, passports were only issued to those individuals whose ancestors had held Latvian citizenship on 17 June 1940 (that is, on the day preceding the launch of the Soviet occupation). Alongside this, additional laws were enacted to establish the category of non-citizens. In response to this move, in subsequent years the Kremlin carried out a passportisation campaign, which resulted in numerous non-citizens being granted Russian citizenship. It is difficult to provide an exact figure for the number of Latvian residents who have obtained Russian citizenship over the last two decades. The Latvian statistical office and the Office for Citizenship and Migration Affairs indicate that in 2022 around 25,000 out of the 40,000 Russian citizens living in Latvia held a Russian passport issued as part of that passportisation campaign.

The early 1990s also saw a process of the Latvianisation of the other most important spheres of the state’s operation. This included the introduction of the country’s own currency (the lats) and the adoption of Latvian as the only official language. The reinstatement in 1993 of the amended version of the constitution adopted back in the interwar period was viewed as a breakthrough because it enabled Latvia to maintain continuity with the pre-war Latvian republic.[7] For many years, the problem of Soviet-era monuments which remained undismantled in the final decade of the 20th century, the Communist crimes which remained unpunished and the role of the Russian culture and language were the subject of endless domestic disputes which were impossible to resolve (this also concerned international disputes, albeit to a lesser degree).

The demolition of monuments as the epilogue of de-Sovietisation

The most recent wave of de-Sovietisation occurred after 24 February 2022. All Latvian political forces and social organisations, including the Social Democratic Party ‘Harmony’, strongly condemned the Russian invasion of Ukraine, and the ruling centre-right coalition decided to end long-term social tensions by introducing revolutionary changes to the public space and education system and by enacting a series of laws on citizenship.

A large portion of the decisions made then, especially those regarding the state’s legal system, was inspired by the logic of the campaign ahead of the parliamentary election held on 1 October 2022. Effectively, this meant that some of the adopted laws were characterised by maximalism and radicalism, which in many instances prevented them from being effectively implemented. It transpired that the main obstacle to a complete de-Sovietisation was not Russia’s former pressure but hasty actions, the absence of comprehensive consultations with social partners, and the failure to take into account the opinions voiced by historians and sociologists on the planned reforms and methods for their implementation.

Resolving the problem of the politics of memory can be viewed as a major success for Riga, as the Russian invasion of Ukraine and the related war crimes have ultimately eliminated the previous modicum of tolerance for celebrating some anniversaries and for cherishing the memories of the Russian-speaking population, which were full of sentiment for the bygone Soviet era.

The May 2022 decision of the central- and local-level authorities to remove the monument located in Victory Park in Riga, which was colloquially referred to as the victory monument or the ‘occu-monument’, was of symbolic significance.[8] The direct motivation for the decision to immediately dismantle this monument involved a response to an illegal gathering organised in front of this landmark (as in previous years the protestors intended to celebrate the USSR’s victory in the Second World War, despite a ban on such celebrations introduced in spring 2022). The removal carried out in September 2022 did not spark any strong public or political resistance. The extremist extra-parliamentary Latvian Russian Union alone organised small protest actions. Nor did the Kremlin offer a particularly strong response (aside from several threats)[9] and this was what Riga and the Latvian media had feared most. The absence of strong objection from the Russian-speaking population and Russia’s insignificant response both suggested that the government’s subsequent decisions would not trigger any serious conflict. Over a hundred more monuments were removed across Latvia and the government launched further, more comprehensive actions focused on the Orthodox Church, the rights of foreigners residing in Latvia and the rule of stripping Latvian citizenship from certain individuals.

The legislative sprint

In 2022, the coalition led by the New Unity party (Jaunā Vienotība, JV) focused on drafting laws to ultimately abandon Latvia’s Soviet past and to sever its remaining social links with Russia. In April 2022, the parliament enacted the law on citizenship, which authorises the state to strip those individuals who openly support the regime in Moscow of Latvian citizenship. Over several weeks preceding the election to the Saeima (1 October 2022) the government carried out numerous reforms. These included Latvia unilaterally disconnecting its Orthodox Church from the Moscow Patriarchate by amending the law ‘On the Latvian Orthodox Church’ (see below). Then, in September 2022, an accelerated reform of the education system was carried out and changes were made to the immigration law was amended. The parliament also amended the immigration law, which resulted in forcing around 25,000 of the 40,000 Russian citizens residing in Latvia to once again legalise their stay and to pass an exam to prove their basic command of the state’s official language (level A2).

Officially, these measures had one specific goal: to sever the ties with Russia in some aspects of life and to consolidate the feeling of Latvianness among the public. However, effectively, the legislative sprint ahead of the election served not only to implement stable and effective reforms to alter Latvian realities, but also to increase the level of support for New Unity.

The Latvian state has encountered numerous difficulties when implementing the laws adopted in 2022, which can collectively be referred to as the de-colonisation laws. Some amendments to the law ‘On the Latvian Orthodox Church’ transforming the local Orthodox Church (which until then had enjoyed autonomy as part of the Moscow Patriarchate of the Russian Orthodox Church) into a fully independent religious organisation turned out to be defunct. The legislators intended the Latvian Orthodox Church to obtain autocephaly[10] without having to carry out a complex canonical process to obtain this status from Moscow or from the Patriarch of Constantinople, who is ‘first among equals’. In autumn 2022, the Latvian Orthodox council adjusted its statutes to the legal requirements and requested Moscow to grant autocephaly to the Latvian Orthodox Church. However, the Moscow Patriarchate, which supervised the Latvian Orthodox Church, rejected both the decisions issued by Latvia’s government and the request submitted by its religious leaders. As a consequence, the Latvian Orthodox Church found itself in an unclear legal and theological situation, as on the one hand it had met the government’s expectations by adjusting its statutes, but on the other hand it had failed to obtain genuine autocephaly.[11] It should be noted in this context that neither the state, nor the Latvian Orthodox Church have openly requested the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople to recognise the Church’s new status.

The new law on citizenship has also proved flawed. In line with the presently valid legislation, the government is entitled to strip anyone who provides non-cash, propaganda and financial support enabling the perpetration of war crimes in Ukraine, of Latvian citizenship. However, on the basis of the 1961 Convention on the Reduction of Statelessness, which is valid in Latvia, such an individual is required to hold citizenship of another country. Thus, Russian oligarch Pyotr Aven (Latvian: Pjotrs Avens), who became a naturalised citizen in 2016, resides in Latvia and has been covered by the EU’s personal sanctions regime, cannot be stripped of his Latvian citizenship. In autumn 2023, inspired by Aven’s case, the government launched work on further amendments to make the law more robust. The coalition led by New Unity has proposed that the government should be entitled to reinstate the status of non-citizens to naturalised Latvians, such as Aven.[12]

A difficult Latvianisation

The immigration law, which was amended in autumn 2022 and required Russian citizens residing in Latvia to once again apply for legalisation of their stay, was subject to several further amendments introduced over the next months. As already mentioned, on the basis of the initial changes, around 25,000 Russians residing in Latvia had to pass a Latvian language exam. Around 1,000 of them have so far not applied for an extension of their stay in Latvia in line with these rules.

Before the present legislation became valid, ‘amended amendments’ were adopted twice: in spring and autumn 2023. Both packages postponed the deadline for submitting the applications and the second package also contained a provision that all individuals who have declared their readiness to take a Latvian language exam will be granted the right to reside legally in Latvia for a further two years. The Constitutional Court is analysing the compliance of these regulations with the Latvian basic law. It is expected to announce its decision on this matter in the first quarter of 2024.

A group of around 1,000 residents, who failed to meet the requirements of this legal act, faced deportation. Deportations were to be carried out after 30 November 2023, that is after the final non-extendable deadline for applying for a residence permit in line with the new rules.[13] Although the individuals in question have received written summonses to leave Latvia, this document does not serve as confirmation that a deportation procedure has been launched.[14] Statements of the Border Guard and the Office for Citizenship and Migration Affairs indicate that in the future any situation concerning deportation will be considered on an individual basis (which means that deportation decisions will not be automatic). In addition, lawyers linked with ‘Harmony’ are planning to block this mechanism. They intend to file requests with the courts to overrule the deportation decisions, or to postpone or block them.[15] Finally, the deportations planned for December 2023 did not take place. In January 2024, employees of the migration office stated that the procedure was difficult to carry out. They thus admitted that, despite earlier announcements, no deportations will be carried out this year either. In addition, as noted earlier, the Constitutional Court may soon annul the provisions of this law, as it is currently analysing their compliance with the basic law.

The crowning achievement of the legislative offensive carried out in autumn 2022 involved the unification of education with Latvian as the language of instruction launched in the 2023/24 school year. Pupils starting their education in that year will study in the official language alone, as the former bilingual system will be cancelled at the beginning of the 2025/26 school year. Alongside this, a reform of foreign language learning has been carried out. Its purpose was to limit the practice of learning Russian as an additional foreign language by replacing Russian with an EU language. Restrictions on learning Russian as an additional foreign language will come into effect at the beginning of the 2025/26 school year.

These initiatives will likely face numerous obstacles. The biggest one will involve the ongoing crisis in the education sector, which is linked with the shortfall of teachers, their low salaries and the reorganisation of the school network outside Riga, which de facto means that small schools in towns and villages are being closed. These problems will be aggravated by other difficulties such as the shortage of teaching staff with sufficient linguistic knowledge to be able to teach in both Latvian and foreign languages. Another problem involves numerous Russian-speaking teachers quitting their jobs. It is likely that the government will only be able to tackle some of these challenges in Riga, and the crisis will particularly affect schools operating far away from big cities.

Summary: inertia instead of a revolution

The de-Sovietisation initiatives the Latvian government has launched since 2022 are encountering numerous obstacles. This is due to the sluggish implementation of the enacted laws, including those regarding citizenship and immigration, and the fact that they contain substantial flaws. The introduced amendments are sometimes defunct or very difficult to implement. The transformation of the public space and the reform of the education sector are likely to be the only fully implemented modifications. The removal of monuments is irreversible, as is the decision to unify the education system, although the ultimate result of the education sector transformation will only be visible in a few years.

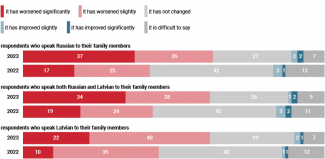

The overall assessment of the ongoing transformation is fairly negative. Contrary to the government’s initial assumptions, they will likely fail to bring the planned result, that is an acceleration of social integration. On the contrary, some reforms may actually widen the former rifts among Latvia’s residents and result in a radicalisation of attitudes. At present, the ethnic Latvians’ narrative targeting their Russian-speaking neighbours contains numerous views which until recently were mainly supported by the local nationalists (see Appendix). Although the Russian-speaking population has expressed concern about the recent reforms, this has not sparked any large-scale protest actions and the government critics remain passive. In the longer term, one manifestation of social discontent will involve a change to the voting preferences of the minority electorate which will become increasingly radicalised. The conciliatory approach promoted by the Social Democratic Party ‘Harmony’ will no longer be popular with Latvians and the public will start to support those movements which will represent the radical and pro-Russian electorate.

Russia has taken note of Latvia’s recent legal amendments. Russian propaganda is mainly focusing on the possible deportation of some Russian citizens residing in Latvia. Although so far no deportation procedure on the basis of the amended immigration law has been launched, Moscow has exaggerated this problem.[16] Regardless of the actual situation, it should be expected that the Kremlin will launch retaliatory propaganda actions, for example another campaign targeting the Baltic states.

APPENDIX

Has the ethnic Latvians’ attitude towards Latvia’s Russian-speaking population changed since the launch of the Russian invasion of Ukraine?

Source: R. Krumm, K. Šukevičs, T. Zariņš, Under Pressure. An Analysis of the Russian-Speaking Minority in Latvia, Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung, Riga, July 2023, library.fes.de.

[1] Although there are many individuals of Russian/minority origin in Latvia’s financial elite, the average Latvian resident of Russian or Belarusian origin is less well-off than the average ethnic Latvian. This is seen on the basis of statistics regarding unemployment, average income earned by the residents of regions inhabited by non-Latvians, the mean age and death rate.

[2] In 2010, ‘Harmony’ came second and won 26.61% of the vote, while in a snap election held in 2011 it came first with 28.62% of the vote. It also won the subsequent elections in 2014 (23.15%) and 2018 (19.92%). In the most recent election held in 2022 it garnered 4.86% of the vote and failed to cross the electoral threshold. For more see B. Chmielewski, ‘Latvian parliamentary elections: victory for the centre-right’, OSW, 3 October 2022, osw.waw.pl.

[3] In the 1990s, around 60 statues of Lenin were removed across Latvia. The total number of all Soviet-era monuments removed back then is unknown.

[4] This happened to the monument to the liberators in Cēsis, which was the first such monument in Latvia. It was designed at the end of the 1940s by Latvian sculptor Kārlis Jansons and built in the town’s Maija park. At the beginning of the 1990s it was in a very bad state of repair. Back in the 1990s, the local government decided against modernising it. Its remains were removed in 2003. In the 1990s, elements of monuments such as the one located in Cēsis were often stolen and sold or recycled.

[5] Article 13 of the Latvian-Russian inter-state agreement ‘On the social welfare protection of retired military personnel residing in the Republic of Latvia and their family members’ signed in 1994 regulates the protection of Soviet symbols of remembrance in Latvia. This protection was increased on the basis on another agreement signed in 2007, which continues to be valid. It concerns places of interment and monuments located at cemeteries; ‘Saeima decides to legally allow Soviet monument demolition’, Eng.LSM.lv, 12 May 2022.

[6] These resulted, among other things, in pressure from EU member states and institutions, which was intended to persuade Latvia to liberalise its approach to ethnic minorities. This pressure, including from France, Luxembourg and the EU, was most intense ahead of Latvia’s accession to the bloc. See M. Jankowiak, ‘Integracja czy dezintegracja państwa? Polityka niepodległej Łotwy wobec mniejszości narodowych (nieobywateli)’ [in:] J. Diec (ed.), Rozpad ZSRR i jego konsekwencje dla Europy i świata. Kontekst międzynarodowy, Kraków 2011, p. 428, after: academia.edu.

[7] The independent Latvian state was proclaimed on 18 November 1918 and continued to exist until 1940, when the USSR cancelled it.

[8] Latvian: okupeklis, its full name is ‘A monument to Red Army soldiers – liberators of Soviet Latvia and Riga from the hands of Nazi German occupiers’. For more, see B. Chmielewski et al, ‘Łotewskie batalie o pomniki’, Komentarze OSW, no. 458, 24 June 2022, osw.waw.pl.

[9] These threats mainly involved announcing vague retaliatory measures (e.g. “Latvia should be brought to its senses”). The key figures of Russia’s administrations, such as foreign ministry spokesperson Maria Zakharova, published offensive social media posts targeting Latvian MPs. M. Шустрова, ‘„Латвию надо вразумить”. Чем Россия ответит на снос памятника Освободителям Риги’, Газета.ru, 12 May 2022, gazeta.ru.

[10] If an Orthodox Church has this status, its head is not supervised by another higher-ranking hierarch.

[11] Although the Latvian Orthodox Church ordains its own bishops without asking Russia for consultation and approval, it continues to be formally (canonically) supervised by the Russian Orthodox Church.

[12] ‘Citizenship revocation for naturalized ‘traitors’ considered’, Eng.LSM.lv, 3 October 2023.

[13] ‘Russian Federation citizens can still apply for a residence permit until 30 November’, Office for Citizenship and Migration Affairs, 16 November 2023, pmlp.gov.lv.

[14] ‘Imigrācijas likuma prasību dēļ 3255 Krievijas pilsoņiem var nākties pamest Latviju’, TVNET, 5 October 2023, tvnet.lv.

[15] ‘Ministrs neizslēdz tiesvedības par iespējamiem lēmumiem saistībā ar Latvijas pamešanu Imigrācijas likuma prasību dēļ’, TVNET, 18 October 2023, tvnet.lv.

[16] The few instances of Russian citizens being deported from Latvia, which Russia has taken note of, were carried out on the basis of a decision issued by the interior ministry and were motivated by security reasons.