Fiala’s government halfway through its term: security reinforcement overshadowed by economic problems

Petr Fiala’s cabinet, which has been in power in the Czech Republic since December 2021, is facing a record decline in support at the halfway point. This is an effect of its waiting too long to address the issues caused by inflation and breaking its promise not to raise taxes. Although living standards in the country have deteriorated, the governing centre-right coalition is pushing through its unpopular budget consolidation package. The backdrop for the government’s poor ratings is the substandard economic performance – the Czech Republic is the only EU country whose GDP has still not reached pre-pandemic levels. This is also partly a result of the country’s very strong trade and investment ties with Germany, which is struggling with numerous economic problems.

At the same time, the Fiala government has undertaken a series of effective actions in areas that had been neglected for years. Ambitious plans for modernising the military are being implemented, and there are successful efforts to radically reduce the dependence on Russian hydrocarbons and nuclear fuel, while the state’s expansion in the energy sector enhances the country’s security. However, cracks are appearing in the strongly diversified five-party government coalition, as individual factions are distancing themselves from the increasingly unpopular Fiala ahead of the European, regional and (partial) Senate elections, all scheduled for this year. Although there are still nearly two years left until the end of the government’s tenure, it is quite unlikely that the centre-right will regain popularity, while the ANO party led by the former Prime Minister Andrej Babiš stands a great chance of becoming the frontrunner in the elections.

The successes

- The energy sector

Improving the country’s energy security is one of the greatest achievements of the Fiala cabinet at the halfway point of its term. At the start of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the Czech Republic was fully dependent on Russian gas and nuclear fuel imports and around 50% dependent on Russian oil imports. Many of its major energy companies were controlled by foreign capital. After two years of the Fiala government’s rule, the Czech Republic gradually ceased importing gas from Russia – in 2023, Russian gas accounted for only 7% of total gas imports. Moreover, gas was not procured through contracts with Gazprom but only through ad hoc purchases on Austrian, Slovak or Hungarian markets, carried out by private Czech gas traders. These companies seize opportunities in price fluctuations and respond to the occasional increases in domestic demand.

An important step towards gas independence was reserving capacity (by ČEZ, which is 70% state-owned) at the FSRU terminal in the Dutch port of Eemshaven for 2022–7. This made it possible to satisfy one-third of the Czech Republic’s demand.[1] This deal was complemented with a contract for capacity at the land-based LNG terminal in Stade near Hamburg that is set to be operational in 2027 and which was announced in November 2023. The latter contract was signed for a 15-year term (and can be extended for a further ten) and allows for the coverage of 25% of the country’s current demand. The state has gained control of the gas pipeline operator Net4Gas,[2] and media reports suggest that ČEZ is about to acquire the largest gas distributor, GasNet. However, the growing role of the state in the fuel sector has been criticised by the press, especially regarding acquisitions made by the state-owned company Čepro, which has become the third-largest owner of fuel stations (EuroOil network) as a result.

Regarding oil, the government (through the state-owned company Mero) has initiated efforts to increase the capacity of the TAL pipeline, which should make the Czech Republic independent of Russian oil by 2025.[3] Since mid-2023, the share of oil imports from Russia has been significantly reduced: from about two-thirds to just over one-third, which was partly a result of the measures taken to adapt the Litvínov refinery (owned by Orlen Unipetrol) to process other types of oil, with a significant portion coming from Guyana and Iraq. The expected increase in the amount of oil transported through the TAL pipeline may also be facilitated by Mero’s anticipated acquisition of shares (32.5%) in Germany’s largest refinery in Karlsruhe, which is connected to the TAL pipeline.

The Czech Republic is also clearly reducing its nuclear energy dependence on Russia. This is demonstrated by the state regaining control of the key Czech nuclear company Škoda JS from the Kremlin-linked corporation OMZ, as well as efforts to replace the Russian nuclear fuel supplier. As part of the latter initiative, the role of Rosatom’s subsidiary (Tvel) will be taken over by the American-Canadian company Westinghouse in 2025 or 2026: independently for the Dukovany Nuclear Power Plant (NPP) and in cooperation with Framatome for the Temelín NPP. However, during the initial phase (for approximately five years), the French company will still supply fuel based on the Russian Tvel’s license (production will be in Germany).

Another point in favour of the government is the relatively efficient implementation of the tender for the expansion of the country’s nuclear energy sector, a task that several previous administrations failed to complete. As a result, by the middle of this year, the general contractor will be selected not only for the fifth unit of the Dukovany NPP but also for three additional units in both the Czech nuclear power plants. However, there is still no comprehensive investment model for this project, which means there may be delays.

- Security and defence

The centre-right government has significantly stepped up the process of modernising the Czech army, which previous administrations had neglected. This year, the Czech Republic is expected to meet NATO’s target of allocating 2% of GDP to defence spending for the first time in over two decades. The government successfully enshrined this commitment into law last spring. Since then, every subsequent cabinet must allocate at least 2% of GDP for defence-related purposes in the draft budget law. This represents a significant change compared to most of the past decade, when defence spending in the Czech Republic ranged from 0.9% to 1.4% of GDP, only reaching 1.5% in 2023. In comparison to 2019, the defence budget increased by 121% in 2024, while the overall nominal growth of budget expenditures was 43%, and nominal GDP reached 34%.

The government has also made its first decisions regarding major contracts for the modernisation of the Czech army. When ANO and the left were in power, these issues were often stalled, partly due to concerns about corrupt ties, which their right-wing predecessors had been unable to avoid. The most infamous example concerned the approved purchase in 2009 of over 100 Austrian Pandur II armoured personnel carriers by the government led by Mirek Topolánek from ODS (his advisor allegedly demanded a bribe from the manufacturer). The unprecedented security challenges in the region caused by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine have helped break the deadlock on military modernisation. Another major factor is the determination manifested by the Defence Minister Jana Černochová, who advocated for maintaining the government’s planned level of defence spending despite general budget cuts. In September 2023, the Fiala cabinet approved the purchase of 24 F-35 fighter jets, which will be supplied to the Czech army between 2031 and 2035. With a cost of just under $5 billion (plus infrastructure construction), this deal constitutes the largest arms contract in the country’s history. The centre-right has thus broken its own record set in May 2023, when the government approved the purchase of 246 Swedish CV90 infantry fighting vehicles for approximately $2.6 billion (with at least 40% of this amount allocated to Czech companies collaborating on the order). The first vehicles are scheduled to enter service in the Czech army in 2026.

- Support for Ukraine

In the past two years, the Czech Republic has been among the world leaders in terms of political and military support for Ukraine. Even before the Russian invasion, it provided artillery ammunition to Kyiv without charge.[4] Fiala, along with the prime ministers of Poland and Slovenia, was among the first leaders to visit the invaded country, heading to the besieged Kyiv. The Czech Republic, alongside Poland, pioneered allied deliveries of tanks to Ukraine (89 T-72M1; the first ones were supplied in spring 2022) and attack helicopters (four Mi-24s). Prague also provided Kyiv with 187 infantry fighting vehicles (131 BMP-1s and 56 PBV-501As), eighteen 2S1 Gvozdika self-propelled howitzers, twelve RM-70 multiple rocket launchers, six 9K35 Strela-10M self-propelled anti-aircraft missile launchers and two batteries of 2K12 Kub guided surface-to-air missiles.[5] The Czech Republic has also supplied significant amounts of small arms for free, or helped train Ukrainian military personnel on its territory. The good intergovernmental relations likely facilitated numerous commercial agreements for the strong Czech defence industry.

The Czech Minister of Defence revealed at the end of 2023 that the country had provided Ukraine with military assistance worth CZK 6.2 billion (approximately $270 million). The ministry also issued licences for commercial deliveries to the Ukrainian army worth CZK 117 billion ($5.1 billion), of which just under half ($2.2 billion) were implemented by the end of 2023.[6] The country’s largest private arms manufacturer, the Czechoslovak Group, doubled its turnover and profits in 2022 largely due to deliveries to Ukraine, and the results for the first half of 2023 indicated further improvement for the entire year. Another Czech arms manufacturing group, STV, increased its turnover fivefold in 2022.

- Presidency of the Council of the European Union

The successful Presidency of the Council of the European Union in the second half of 2022 was, undoubtedly, one of the Fiala government’s achievements. As a smaller state, the Czech Republic found it easier to play the role of a neutral arbiter than larger states like France, which had preceded it. Consequently, it was able to make progress on key issues. The Fiala administration made particularly intensive and effective moves in Brussels to improve energy security, especially as EU members were distancing themselves from Russian hydrocarbon supplies at that time, and to mitigate the surge in energy prices (during this period, a total of 12 meetings were convened in the format of ministers in charge of energy issues).

It was also important that support for Ukraine retained a high priority on Brussels’ agenda, while Prague’s hosting of the first summit of the European Political Community, a forum for strategic discussions that brings together leaders of most European countries, not just EU leaders, provided a helpful stage to put forward this key topic. The Czech Republic achieved one of its greatest successes in EU enlargement policy: it helped Bosnia and Herzegovina gain candidate status, Kosovo’s membership application was accepted, and the long-delayed visa liberalisation for Kosovo was agreed upon. During the Czech presidency, Croatia’s accession to the Schengen area was approved from 2023. However, Romania and Bulgaria were not approved as Schengen area member states due to opposition from Austria and the Netherlands.

The smooth running of the presidency helped the Czech Republic improve its image, which had been tarnished during the previous EU presidency in 2009, when Mirek Topolánek’s government fell (and was replaced by a caretaker government). However, the incumbent government failed to sufficiently promote its successes at home, and as a result, the presidency was evaluated as average by most Czechs in an opinion poll carried out at that time.[7]

The setbacks

- Controversial reforms

The main reasons for the falling popularity of the Fiala government are economic problems and the unpopular measures it has made to address these problems, some of which meant breaking pre-election promises. Although the government argued it had no other way out, a more comprehensive analysis raises doubts as to whether such radical steps were necessary. The government’s flagship project is the so-called ‘consolidation package’, aimed at reducing the country’s debt level. This issue was prioritised because the ideology of economic liberalism has a strong influence within the main coalition party, ODS in the smaller TOP 09 party and generally in the mainstream media debate. During the Covid pandemic in 2020–1 (when the previous coalition was still in power), the budget deficit as a percentage of GDP was the highest since the establishment of the Czech Republic in 1993 largely due to emergency expenditure (though it still was not among the most largest in the EU – in 2021, ten other member states had larger budget shortfalls). When the centre-right was in opposition, it repeatedly emphasised this fact, and one of its main promises was to reduce the deficit once in power. However, it also compromised on development spending in order to fulfil this promise. The declining standard of living – also a result of the cuts – continues to stifle the economy, and non-competitive VAT rates on essential goods are one of the reasons for mass cross-border shopping tourism (especially to Poland).[8] At the same time, the Czech Republic is one of the least indebted EU countries, as its public debt relative to GDP stands at 44%, well below the EU average (83%), and is in a better position than any of its neighbouring countries, including Germany (65%) and Poland (49%).

The increase in some taxes as part of the ‘consolidation package’ came as a shock to many liberal centre-right voters. This move was in blatant contradiction to the pre-election promise of not raising fiscal burdens, which was reiterated during the first year of the coalition’s rule. Corporate Income Tax (CIT) has risen from 19% to 21% since the beginning of 2024. Additionally, property tax and excise duties on tobacco and alcohol products have increased. Moreover, as part of the changes in VAT rates (three rates have been replaced with two: 12% and 21%), the VAT rate on certain products (such as most beverages) and services (such as hairdressing) has been raised. The government had to search for additional budget revenues partly due to these falling significantly since the income tax was reduced by the previous parliament with votes from ANO as well as ODS itself.[9]

ODS’s dogmatic approach to budgetary issues dictated its cautious approach to mitigating the effects of inflation, including limiting the rise in energy prices. As a result, the Czech Republic was the EU country most affected by the consequences of the global energy crisis. In the second half of 2022, no other country in the EU experienced such significant increases in gas prices (231% y/y) as the Czech Republic did, while the increase of the price for electricity (97%) was lower only to Romania (in Germany, the increases were 36% and 4%, respectively).[10] Other public policies have also suffered due to the government’s actions or failure to act. The government’s agenda included ambitious declarations that education would be prioritised, meanwhile expenditure in this area is expected to increase by only 1.5% nominally this year. Earlier, in the budget for 2023, an increase of 4% in funds for this sector was envisaged, even though inflation hit double digits throughout the year. It is this sector that has protested most of all since the elections – last November, one of the largest strikes since 1989 affected 74% of educational institutions: kindergartens as well as primary and secondary schools. The protesters demanded wage increases for support staff – from kitchen staff to psychologists and teacher’s assistants. Although it is already difficult to find workers for these positions due to low wages (and negligible unemployment), the government has proposed to actually cut funds for their salaries by 2% next year.

Prime Minister Fiala rejected the protesters’ demands, claiming that they were politically motivated, and concluded that “there is no room for concessions” because the austerity package was necessary (the government only agreed to assign relatively small additional funds for this purpose at the end of January this year). The media has expressed surprise at this treatment of education sector by a cabinet that is sometimes dubbed the ‘government of teachers’, because every third member of the cabinet has teaching experience or has been trained as a teacher, and Fiala himself used to serve as the rector of the Masaryk University in Brno, the second-largest university in the Czech Republic.[11]

- Economic stagnation and declining living standards

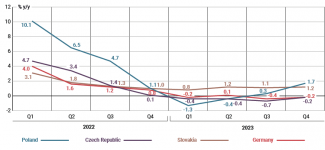

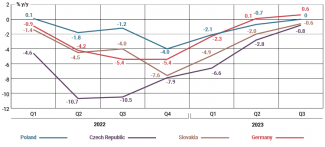

The Czech economy is the only one in the EU not yet to have reached pre-Covid GDP levels (see chart 1). Household consumption has experienced a decline (y/y) in six out of the last seven quarters; its value is currently at the level of 2016, and 9% below pre-pandemic levels. Real wages in 2022 decreased most sharply in the region in the Czech Republic (by 8%, compared to Poland and Germany where it was a 2–2.5% fall), and the downward trend continued during the first three quarters of 2023 (-3.4% y/y; see chart 2).

Chart 1. Changes in the Czech Republic’s GDP in 2022–2023 as compared to selected neighbours

Source: author’s own estimates based on data from individual countries’ statistical offices. GDP, adjusted for seasonal variations, in constant prices.

Chart 2. Real wage changes in the Czech Republic in 2022–2023 as compared to selected neighbours

Source: author’s own estimates based on data from individual countries’ statistical offices.

The Czech public is blaming the government’s policies for the deterioration of living standards, but the government’s actions (or lack thereof) have had only a partial impact on this situation. Consumption has been dampened to a certain extent due to the central bank’s tight monetary policy, which began raising interest rates from the so-called technical zero as early as spring 2021, while, for example, Poland did so only at the end of that year, and the European Central Bank followed suit in mid-2022. At the same time, the level of the reference interest rate (lowered to 6.25% as late as February) is higher in the Czech Republic than in Poland (5.75%) and the eurozone (4.5%), but still lower than in Hungary (10%). Despite these measures, the Czech Republic had the highest level of inflation in the EU in December 2023 (7.6% y/y).

The Czech economy has also suffered due to structural and cyclical problems in the German economy, with which it is most strongly connected in the region. One-third of Czech exports go to Germany (for comparison, the same figure for Poland is 28% and for Slovakia, it is 21%). As demonstrated by an analysis by the Erste Group Bank, no other country in the region has been affected by Germany’s economic troubles as acutely: a 0.5% decrease in Germany’s GDP leads to a nearly 0.25% reduction in the Czech Republic’s GDP (in Poland, the decrease is half that rate).[12]

- The government’s low support ratings and poor communication

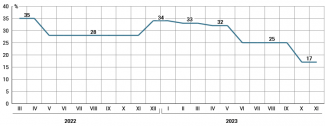

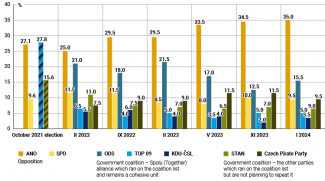

Due to all these problems, public support for the government has plummeted. A survey by the CVVM agency conducted last December has revealed that only 17% of Czechs trust the Fiala cabinet.[13] This is not only the worst result among the eight so-called constitutional institutions (for comparison, the president is trusted by 52% of citizens). It is also the worst rating for the government since 2013, when Petr Nečas, Fiala’s direct predecessor as ODS leader, headed a centre-right cabinet. The government should be equally concerned by the speed with which it is losing popularity: it more than halved over the past year (see chart 3). In turn, the total support rating for the five parties of the government coalition is about 3.5 percentage points lower than during the elections, while ANO’s ratings are just under 8 percentage points higher (see chart 4).

Chart 3. Public trust in Petr Fiala’s government

Source: author’s own estimates based on data from the CVVM agency.

Chart 4. Support for the political parties present in the Chamber of Deputies since the election in autumn 2021

Source: author’s own estimates based on data from the Kantar agency.

The governments ratings, in addition to its specific actions or lack thereof, are also adversely affected by the strategy of its communication with the public. The academic language used by the prime minister, who is a political science professor, seems to be more suited for international rather than domestic communication. It starkly contrasts with Babiš’s straightforward messages to the electorate which often refer to Czechs’ everyday lives as well as purely entertainment issues. In his public statements Fiala typically focuses on more abstract macroeconomic problems or issues concerning the international situation.

At the same time, Fiala showed little understanding for the worsening living conditions of the country’s residents. In a professorial tone, he reminded his fellow citizens that, on a global scale, the Czech Republic is among the countries with the highest standard of living, which they should be grateful for. Furthermore, he claimed that support for the government was falling due to excessive scepticism among the Czech public rather than the government’s actions. A video of the prime minister filmed in a German supermarket, in which he ‘discovers’ that many products there are cheaper and of better quality than in his own country, was a symbol of his PR disaster. Since this is common knowledge, many Czechs realised how much he was out of touch with their daily concerns, especially since his ‘discoveries’ were not followed by actions that could change the situation.

Prospects for the Fiala cabinet

It is unlikely that the parties of the government coalition will manage to regain public trust by the parliamentary elections scheduled for autumn 2025. The probable winner is ANO, whose shift in communication strategy has enabled it to also reach the youngest generation of voters, not only the elderly, who have traditionally formed the core of Babiš’s electorate. Additionally, the increasing discord within the coalition does not bode well for the centre-right parties.

The second-largest party in the coalition, the centrist STAN (Mayors and Independents), sees the halfway point of the government’s term as an opportune moment to distance itself from the rest of the coalition parties. Its leader is currently touring the country, subtly criticising Fiala in his speeches. Furthermore, STAN politicians independently created the position of a Euro Adoption Commissioner who would closely cooperate with the minister representing the STAN party, but they eventually had to give up this idea under pressure from the ODS, which is opposed to introducing the euro in the Czech Republic. It cannot be ruled out, however, that in 2025, another rival will emerge who will challenge the parties from the incumbent government coalition, since Miroslav Kalousek, a former finance minister in centre-right governments associated with austerity policy, aims to appeal to disillusioned centre-right voters. Paradoxically, he criticises the government for being insufficiently ambitious with its austerity package, and his party is set to be named the Fiscal Responsibility Party (SRO).

The parties participating in Fiala’s government will face their first electoral tests in 2024, as the European Parliament (EP) elections are scheduled in spring, while in autumn regional councillors as well as one-third of the Senate will be elected. The European elections have no direct impact on domestic policy and typically do not attract much interest in the Czech Republic (turnout has never exceeded 30%), but the autumn elections could be a stronger signal for a shift in support. At the same time, some consolidation has been seen within a section of the government coalition comprising three parties forming the Spolu (Together) alliance: namely ODS, TOP 09 and the Christian Democrats. Despite significant differences in their approach to European policy, they have decided to create a joint list for the EP elections. However, both opponents and proponents of closer European integration (including adopting the euro) are on the list, which may discourage voters with clear views on this issue and redirect their attention to lists representing a more consistent approach.

Fiala himself has suggested that some adjustments will be made, at least in terms of communication with the public, by announcing that a period of sacrifices will be followed by a time of reward. However, economic forecasts for the Czech Republic (and Germany, upon which its economy heavily relies) are only moderately optimistic. After a GDP decline in 2023 (-0.4%), slight growth is projected for 2024: ranging from 0.6% (the Czech central bank) to 1.4% (the European Commission). With a strong dependency on exports and thus on the condition of the global economy, the government has limited options to reverse negative trends. Nevertheless, the centre-right will have to make some adjustments for the sake of political pragmatism. Therefore, on the one hand, changes in communication with the public can be expected, and on the other, attempts will be made to expose the ‘human face’ of the government coalition along with some pro-social gestures. However, this carries the risk of deepening rifts within the coalition, and a bad result in this year’s European, regional and Senate elections may further undermine Prime Minister Fiala’s position.

[1] See K. Dębiec, A. Łoskot-Strachota, ‘Czechy z udziałem w holenderskim terminalu LNG EemsEnergyTerminal’, OSW, 16 September 2022, osw.waw.pl.

[2] See K. Dębiec, ‘Czechy: Net4Gas w rękach państwa’, OSW, 28 September 2023, osw.waw.pl.

[3] Idem, ‘The TAL is expanding: the Czech Republic is gaining independence from Russian oil supplies’, OSW, 7 December 2022, osw.waw.pl.

[4] Idem, ‘Czechy w awangardzie wsparcia dla Ukrainy’, OSW, 28 January 2022, osw.waw.pl.

[5] See Deliveries of major categories of military equipment to Ukraine, osw.waw.pl.

[6] ‘‚Vzpruha pro obranný průmysl.‘ Česko vydalo licence na komerční dodávky zbraní Ukrajině za 117 miliard’, iROZHLAS, 12 December 2023, irozhlas.cz.

[7] The ratings in the Media agency survey conducted on 17–18 December 2022 indicate that this period was not generally evaluated as being out of the ordinary: in the opinion of 12% of respondents the presidency was perfect, 21% very good, 22% good, 17% acceptable and 13% poor (15% of respondents had no opinion).

[8] In 2023, the VAT rate on basic food products was 15%, and since the beginning of this year it has been reduced to 12%, whereas in Poland, the zero rate still applies.

[9] See K. Dębiec, ‘The Czech fiscal reform: a major income tax cut’, OSW, 27 November 2020, osw.waw.pl.

[10] Eurostat data.

[11] M. Čaban, ‘Komentář: Vláda učitelů škrtí školství. Nepochopitelné’, Seznam Zprávy, 8 September 2023, seznamzpravy.cz.

[12] CEE Special Report | To what extent is CEE resilient to German slowdown?, Erste Group, 3 November 2023, erstegroup.com.

[13] Důvěra ústavním institucím – podzim 2023, CVVM, 14 December 2023, cvvm.soc.cas.cz.