Running on European tracks. Modernising the rail network in western Ukraine during wartime

The Ukrainian government has used the ongoing war as an opportunity to carry out a rapid transformation of the railway infrastructure in the western part of the country. This process is expected to both increase the capacity of the railway lines leading to the EU in the short term, and to result in the local logistical hubs taking over a significant share of the added value generated by rail transhipment operations. The construction of a large hub at Sknyliv near Lviv is the key element of the government’s plan. Due to the building of the standard-gauge railway to the border, plans have been made to connect the future hub to the rail networks of Poland and Romania as soon as possible, alongside the terminal at Mostyska which operates nearby.

Kyiv’s actions fit well with the EU transport plans. However, if Ukraine decides to carry them out unilaterally and fails to take the interests of its neighbours into account, the railway issue may become another source of tensions in the trade sector and provoke protests from the Central European rail and logistics industry. Therefore, the ideal scenario would involve the immediate launch of consultations between the region’s states and Ukraine regarding the model of transport relations based on border infrastructure. EU companies should be granted equal access to development and business opportunities in the hubs which are currently being built in Ukraine, as part of the liberalisation of the railway market within the framework of the process of Ukraine’s accession to the EU.

The Russian invasion has forced Ukraine to rapidly modernise and transform its rail links with its EU neighbours and Moldova to increase the capacity of cargo transport and passenger traffic. This has boosted the importance of cross-border infrastructure links with the Central European states, which played a much less significant role in handling Ukraine’s foreign trade after the collapse of the Soviet Union. Previously, Ukraine’s economy had largely relied on trade with the East and on dispatching its exports to global markets via its own ports on the Black Sea. It has proved necessary to accelerate the modernisation of Ukraine’s rail links both in the context of the Russian blockade of these ports (which has partially been lifted), and the prospect of EU membership. Ukraine’s current priorities include a plan to extend standard-gauge railways (that is, the 1435-mm gauge used in the vast majority of the EU, as opposed to the 1520-mm broad-gauge railway which predominates in Russia and the post-Soviet states) from the EU member states into its territory, to increase the number of passenger trains and to ensure the usability of the existing broad-gauge links.

The government in Kyiv has announced that its long-term goal is to replace the broad-gauge railway with a standard-gauge one throughout the country. However, this will take many years and will cost at least tens of billions of euros. So for the time being, the plan is to extend the standard-gauge railway, especially from the Polish border to the Ukrainian railway junctions in Sknyliv near Lviv and in Mostyska. In the longer term, this railway will connect Lviv with Uzhhorod, Kovel and Chernivtsi, and ultimately to establish connections via this railway to Kyiv and the eastern part of the country.

Since the outbreak of the war, Kyiv has successfully carried out numerous investment projects which are elements of this plan (see Appendix), including the links leading to Poland (Izov–Kovel, the Khyriv railway junction), Romania (Rakhiv–Berlebash–the state border and Teresva to the state border) and Moldova (Berezyneto the border crossing point at Basarabeasca). It should be expected that the railway lines connecting Ukraine with Poland and Romania will become the primary routes for transporting local goods. Ukraine’s decisions have come in response to the economic processes triggered by the Russian invasion and to the emergence of new logistical chains, as these two directions have proved to be the most important for sustaining Ukraine’s economy and war effort (as regards Romania, this mainly involves the supply of cereals and bulk cargo; as regards Poland, bulk, containerised cargo, humanitarian and military aid). If the capacity of the rail network in these regions improves, this could also significantly bolster Poland’s connectivity through Ukraine with countries such as Romania and Moldova (via the Przemyśl/Lublin–Lviv–Suceava corridor), as well as Slovakia and Hungary (via the Chop railway junction in Zakarpattia).

At present, Hungary and Slovakia are not particularly interested in developing rail infrastructure with Ukraine (see Appendix). The government in Bratislava is not seeking to modernise these links, although it may modify its stance should the EU allocate more funds for this purpose. Hungary, for its part, has extensive and recently upgraded rail and terminal infrastructure on the Ukrainian border, which could be used to transport goods to the Adriatic ports and on to the Italian market. However, cooperation in this area has so far been insignificant for several reasons, probably including political tensions between the two countries.

At least since the Lugano conference on Ukraine’s reconstruction, Kyiv’s intention has been to shift the transshipment operations carried out at Polish and Ukrainian cross-border terminals to logistical hubs in the vicinity of Lviv (Sknyliv and Mostyska). Thus, the extension of the standard-gauge railway will not only ensure increased railway network capacity, but will also facilitate the transfer of profits from the freight forwarding operations (which at present are carried out at Polish hubs on the Polish-Ukrainian border and in other locations) to Ukrainian hubs located in Lviv oblast.

2022 saw the inauguration of a new terminal in Mostyska. It is 50% owned by Lemtrans, Ukraine’s biggest private rail carrier, which is a component of the SCM holding company controlled by the country’s richest oligarch Rinat Akhmetov. The facility offers transhipment of containerised, general and bulk cargo (dry cargo, mainly cereals, and liquid cargo, including sunflower oil) between the broad-gauge and standard-gauge railways. Its annual capacity is 5 mn tonnes of various types of cargo, including cereals (60,000 tonnes monthly).

Both the central- and the local-level authorities are interested in establishing a transport hub in Sknyliv, which in the future could be capable of serving the trans-European corridors leading to Kraków, Warsaw, Constanța, Budapest and Bratislava (see Appendix). Plans have also been made to establish a railway link to the nearby Lviv airport, which before the war was used by almost 2 million passengers annually. According to Yevhen Lashchenko, the CEO of the Ukrzaliznytsia company, a new railway station, intended to handle traffic incoming from Poland, and a logistical terminal are to be built in Sknyliv by 2026.[1]

The EU’s vision of the Ukrainian rail link

The European Commission also views Ukraine’s shift to the standard-gauge railway as a gradual process. In July 2023, the EC published a feasibility study in cooperation with the European Investment Bank (EIB) analysing the possible scenarios for implementing this plan.[2] According to the document, at the beginning it would be economically rational to build a standard-gauge railway to handle international passenger traffic and container transport (especially in the east–west direction) and then to modify the track gauge nationwide. The EC has endorsed this model of transition since the outbreak of the war, although at the same time it is increasingly aware that the individual activities need to be carried out in stages to the high cost of this initiative.[3]

According to the study, the estimated cost of modernisation of one kilometre of a broad-gauge railway is €1–1.1 mn, while full transition to the standard gauge may cost up to eight times more. This means that the refurbishment of the railway running from Medyka to Kyiv could cost around €600–700 mn, while its full transition may cost up to €5–6 bn.

It cannot be ruled out that Kyiv will need to bear this cost, as it is likely that for security reasons it will be unable to reduce the infrastructure’s capacity during the period of its modernisation, and will thus decide to build a new standard-gauge track on the most important sections of the route. One provisional solution, which will most likely be applied during the transition period, could involve transforming one of the two parallel broad-gauge tracks into a standard-gauge track.

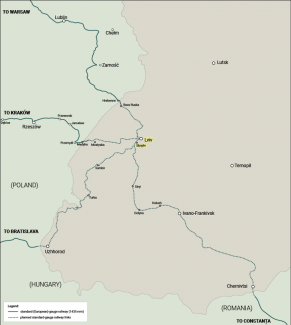

The EC proposal announced in July 2022, amending the regulation on the TEN-T network and relating to the expansion of four transport corridors to Ukraine and Moldova, is expected to facilitate the implementation of this vision.[4] It involves the Baltic Sea–Adriatic Sea, North Sea–Baltic Sea, Rhine–Danube corridors and the recently established Baltic–Black–Aegean Seas corridor (see Map 2). In line with the amended regulation, priority will be given to the construction of a standard-gauge rail link from Rzeszów via Medyka to Lviv and further on to Romania and Moldova. This link was also included in the TEN-T core network, which means that it should be built by 2030. As a result of a revision carried out in December 2023, the EC decided to raise the status of the route from Lublin via the border crossing point in Dorohusk to Kyiv by including it in the TEN-T extended core network which is expected to be built by 2040.[5]

Due to the revision of the TEN-T, Ukraine should gain easier access to European funds for the expansion of standard-gauge rail infrastructure of trans-European importance. Although since as early as 2022 the EC has signalled its disapproval of using these funds to modernise broad-gauge railway links, the ban will probably only apply to new projects. Several projects involving the modernisation of broad-gauge railways have already been launched using funds from Ukraine’s state budget, which is co-funded by the EU. For example, the report compiled by the EC and the EIB contains a proposal to increase the capacity of the Broad Gauge Metallurgy Line (LHS) running from Ukraine to the town of Sławków in Poland’s Silesia region.[6]

Financial challenges

The lack of funds is an obstacle preventing Kyiv from carrying out its planned initiatives. At present, Ukraine can hope to receive assistance, and that rather insignificant, from the EU and the US alone. On 25 November 2023, Ukrzaliznytsia and the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) signed a memorandum regarding this matter; the initial stage of its implementation will involve a feasibility study (previously it was stated that this document had already been compiled). According to a press release published on 4 December, USAID intends to earmark $225 mn for this purpose.[7] Kyiv’s initial cost estimate regarding the construction of a standard-gauge railway link between Mostyska and Lviv stood at 1.8 bn hryvnias (around $50 mn), which is several times less than the value of the USAID’s planned assistance.

In June 2023, Ukraine and the EU signed an agreement on including this country in the Connecting Europe Facility (CEF). This will enable Ukrainian companies operating in the transport and other sectors to apply for EU funding, despite the fact that these funds come from a pool allocated to the member states and Moldova. In the CEF Transport programme unveiled in September 2023, in which the deadline for submitting proposals was the end of January 2024, the pool of funds available to be disbursed is €7 bn. Ukrzaliznytsia has launched negotiations with the Directorate-General for Mobility and Transport (DG MOVE) on receiving support from this programme. Kyiv is hoping to receive funds for three or four projects, including the priority project involving the construction of the Mostyska–Sknyliv railway link. In the CEF’s first call for proposals, in which Ukraine was allowed to take part, two projects involving the construction of road and railway border crossing points between Poland and Ukraine have been selected. These investment projects envisage several initiatives including the modernisation of around 57 kilometres of railway lines, which is intended to streamline the operation of the border crossing points in Yagodyn and Mostyska.

The European Bank of Reconstruction and Development is another possible source of funding. In June 2023, Ukrzaliznytsia signed a €200 mn loan agreement with this bank. These funds will mainly be spent on boosting the capacity of the railway border crossing points between Ukraine and EU member states and on modernisation of the rolling stock. The United States, the Netherlands and France have declared their intention to co-fund these projects, as has the EU (separately).

The future of railway links via the border with Poland

The wartime transformation of Ukraine’s railways has resulted in both a boost to the infrastructure capacity and a new distribution of added value from handling foreign trade. On the basis of previous experiences regarding cooperation between Poland and Ukraine in the area of rail transport, it can be stated that the key challenge will involve finding a mutually beneficial solution as regards the location of transshipment and logistical hubs to handle trade. The connection between the standard- and broad-gauge tracks will no longer be located in the vicinity of the border but will move closer to Lviv and Kovel, and thus Kyiv will earn additional income on the transshipment of goods and their logistical handling.

As compensation, the Polish transport sector will probably expect to be allowed to open its own terminals in the new hubs. It would also like Ukraine to ensure it equal access to the local rail and transshipment facilities, the so-called ‘level playing field’. The liberalisation of the railway market and the introduction of investor-protecting regulations, which will be devised as part of the process of Ukraine’s accession to the EU (negotiation clusters 2: Internal Market, and 4: Green Agenda and Sustainable Connectivity), will be among the factors which could help to achieve this goal. Due to the need to maintain the stability of supplies across the border, it is also very important for the Ukrainian side to guarantee the smooth operation of the LHS, as there have been disputes between Warsaw and Kyiv over this issue in the past.

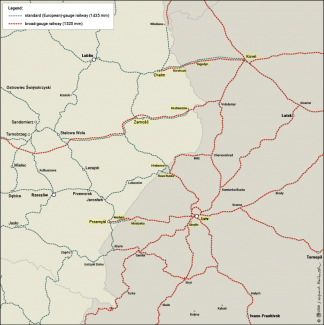

At present, 7 out of the 15 formally existing railway border crossing points between Ukraine and the EU are located on the border with Poland (see Map 1), although only four are currently operational: Hrubieszów–Izov (the only one equipped with a broad-gauge track; PKP LHS is its operator and the only carrier operating on the Polish side), Medyka–Mostyska, Werchrata–Rava Ruska and Dorohusk–Yagodyn. In the long term, they will play the key part in Ukraine’s post-war reconstruction and its economic integration into the EU. In the case of six of the other border crossing points, the junction between the standard- and broad-gauge track is located in the border belt, which is economically favourable to Polish logistical hubs, including those located in the vicinity of Chełm, Zamość, Przemyśl-Medyka and Hrebenne. Revenue earned from the logistical and warehousing operations, which involve the stopping of cargo trains, changing the track gauge and the transshipment of goods, is an important source of income for the local economies. In this context, the LHS is of particular importance. Several important and dynamically developing logistical and transhipment hubs have been located along its route of around 400 km.

While the implementation of these projects may foster the process of logistical activity shifting from border regions closer to the Ukrainian hubs, it has also created opportunities to attract Ukrainian cargo flows to Polish ports. Due to the low level of security in eastern Ukraine, the country’s economic activity is increasingly shifting westwards. As part of the ongoing revision of the TEN-T network, the EC has also recommended that Ukraine’s production facilities should be located in the western part of the country, in the vicinity of the standard-gauge railway. Since the distance between Lviv and Gdańsk is the same as between Lviv and Odesa (around 800 km), there is no doubt that even after the end of the war Polish ports will continue to play an important part in serving the Ukrainian market, for example as regards the transport of containerised cargo to the UK, Scandinavia and the US.

It should be assumed that when the war is over, the specially adjusted Ukrainian ports will continue to handle bulk goods with small profit margins, such as cereals and ores. A return to these trends has been evident since the launch of the new Black Sea corridor in September 2023, which comprises the three ports of the so-called greater Odesa.[8] However, the Ukrainian ports’ present potential as regards handling container trade is relatively small. Prior to the Russian invasion, they transhipped a total of 1 mn TEUs annually (only a third of the figure for Polish ports), and increasing their capacity in this sphere would both require major financial outlays and take time.

APPENDIX

Progress in the modernisation of transport links between Ukraine and the EU

Completed investments

- In June 2022 Ukrzaliznytsia completed the electrification of a 94-km long railway section running from Kovel via Izovto the Polish border.

- In 2022 the Kovel–Yagodyn–Polish border standard-gauge railway was modernised.

- On 17 February 2023 Ukrzaliznytsia finished the refurbishment of railway lines along the following routes: Polish border–Staryava–Khyriv and Polish border–Nyzhankovychi–Khyriv. A standard- and a broad-gauge track have been built there.

- October 2023 saw the launch of passenger service from Warsaw to Lviv. Although for the time being passengers change trains in Rava Ruska (where the standard-gauge railway ends), Ukrzaliznytsia is planning to build a standard-gauge railway between Rava Ruska and Lviv. This will be the first standard-gauge link with a Ukrainian oblast capital.

- On 25 March 2023 a railway border running from the Berezyne–Basarabeasca (Moldova) crossing point was opened. As part of this initiative, 23 km of track on both sides of the border were modernised. This route will facilitate the transport of cargo to the ports of Reni and Izmail.

- August 2022 saw the inauguration of two new railway sections: Rakhiv–Berlebash–the Romanian border and Teresva to the Romanian border.

Planned investments

- Ukrzaliznytsia has announced its plan to build a standard-gauge railway on the Mostyska–Sknyliv section (near Lviv). On 25 November 2023, it signed a memorandum with USAID regarding this project. According to a press release published on 4 December 2023, USAID intends to earmark $225 mn for this purpose.

- Plans have been made to build a standard-gauge railway between Lviv and Chop (on the Hungarian border), Uzhhorod and Matovce in Slovakia.

- In May 2023 Ukrzaliznytsia and Calea Ferată din Moldova (the Moldovan national rail company) signed a memorandum to modernise the railway from Vălcineț (which borders on Vinnytsia oblast) to the town of Căinari, which is linked with the port of Reni on the Danube. The agreement is expected to facilitate the logistical handling of Ukrainian agricultural produce which is transited via Moldovan territory. The cost of the project stands at €32 mn, and its expected completion date is the end of 2024.

- There are plans to build a 585-km long section of a standard-gauge railway between Kyiv and the Polish border in order to launch a high-speed rail service between Warsaw and Kyiv. The project is to be carried out in 2026–2032.

- In January 2023 Ukrzaliznytsia signed a memorandum with the Polish CPK Sp. z o.o. company (which is planning to build the Solidarity Transport Hub (STH) near Warsaw) regarding the construction of a high-speed rail link (with a maximum speed of 250 km/h) on the Warsaw–Lublin–Lviv–Kyiv route (via Rava Ruska), which will be an extension of the STH’s ‘spoke’ no. 5 leading to Lviv. The agreement envisages several joint projects including the preparation of a feasibility study for the planned new railway line between Ukraine and Poland.

- On 20 November 2023 Ukrzaliznytsia signed a cooperation memorandum with representatives of the South Korean ministry of infrastructure and transport, the Korea Railroad Corporation and Korea National Railway. The document is a declaration of support for the implementation of seven projects: these include the construction of high-speed railway to the Polish border (no details have been provided), the plan to increase the capacity of the Odesa–Izmail–Reni railway line and the construction of a new rail traffic control centre.[9] In addition, the Korean Hyundai Rotem company will be responsible for the organisation and maintenance of the rolling stock and for equipping the repair facility in Ukraine.

Slovakia’s and Hungary’s plans regarding the modernisation of their rail links with Ukraine

Aside from Poland and Romania, at present Ukraine’s neighbours do not have any major plans regarding the expansion of their rail links with that country, although it cannot be ruled out that this will change in the future. In Slovakia, the government led by PM Fico, which came to power in autumn 2023, has announced its intention to give priority to the expansion and modernisation of rail infrastructure, and to seek to obtain EU funds to carry out its investments in the regions bordering on Ukraine. However, while no detailed plans have so far been unveiled, the assumptions of this programme seem to suggest that the government will focus on domestic rail links. Expansion of the rail links in border regions will depend on decisions coordinated with Brussels as regards the spending of possible additional funds to support Kyiv. Bratislava intends to use a portion of these funds for this purpose. At present, the only major railway line linking the two states runs from Košice via Čierna nad Tisou in south-eastern Slovakia to the Chop railway junction in Zakarpattia and further on to Mukachevo. This route (in the opposite direction) is used to transport 10–15% of Ukraine’s agricultural exports as part of the so-called Solidarity Lanes via the EU. Čierna hosts a transshipment terminal for cargo transported via the broad-gauge railway (this is where the trains are switched to standard-gauge tracks). It is involved in several current and future investment projects (mostly CEF projects), mainly aimed at facilitating the transport of Ukrainian grain. In the past, Slovakia intended to extend the broad-gauge railway line and to take over a portion of cargo transit incoming from China. However, these plans have now become irrelevant as Ukraine’s border regions seek to shift to standard-gauge railways.

Hungary has sought opportunities to expand its railway junction in the vicinity of the Ukrainian border for many years. January 2021 saw the launch of the construction of the East-West Gate intermodal terminal at a location around 20 km from the village of Fényeslitke. It was inaugurated in October 2022, and has five 1520-mm gauge tracks and five 1435-mm gauge tracks. Its target transshipment capacity is around 200,000 TEUs annually; it has also been equipped with the 5G network (built by Vodafone Hungary and Huawei Technologies Hungary). The investment, which is an element of the project to modernise the dry transhipment port in Záhony, was intended to attract cargo from China incoming via the railroad system of the Belt and Road Initiative, which was expanded during the pandemic. However, for the time being, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has annulled the business assumptions of this investment. At present, the terminal is being used for the transshipment of Ukrainian grain to the Adriatic ports, and is one of the fastest supply routes. However, the Hungarian government is hoping that the initial purpose of this dry port, that is to expand links with China, will be reinstated as soon as possible.

Map 1. Polish-Ukrainian railway infrastructure in border regions

Source: the authors’ own analysis.

Map 2. TEN-T connections in Ukraine

Source: the authors’ own analysis.

Map 3. Rail links around the terminal in Sknyliv

Source: the authors’ own analysis.

[1] M. Szymajda, ‘UZ: Budowa torów 1435 mm od granicy do Lwowa możliwa w 2024 roku’, Rynek Kolejowy, 8 November 2023, rynek-kolejowy.pl

[2] Strategy for the EU integration of the Ukrainian and Moldovan rail systems, European Commission, European Investment Bank, 11 July 2023, jaspers.eib.org.

[3] Solidarity Lanes: study on EU rail connections with Ukraine and Moldova suggests deploying European track gauge on key linesets out step-by-step plan for better EU, European Commission, 10 July 2023, transport.ec.europa.eu.

[4] Commission amends TEN-T proposal to reflect impacts on infrastructure of Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine, European Commission, 27 July 2022, transport.ec.europa.eu.

[5] ‘Trans-European transport network (TEN-T): Council and Parliament strike a deal to ensure sustainable connectivity in Europe’, Council of the European Union, 18 December 2023, consilium.europa.eu.

[6] Strategy for the EU integration of the Ukrainian and Moldovan rail systems, op. cit., pp. 111–112.

[7] ‘Партнерство USAID з «Укрзалізницею» сприятиме інтеграції України до Транс’європейської транспортної мережі ЄС’, USAID, 4 December 2023, usaid.gov.

[8] S. Matuszak, J. Ber, ‘Ukraine: the new Black Sea corridor is a success’, OSW, 22 December 2023, osw.waw.pl.

[9] J. Newton, ‘Korea steps in to help Ukraine reconstruct railway’, International Railway Journal, 23 November 2023, railjournal.com.