Unequal competition. The consequences of the liberalisation of EU–Ukraine road carriage for Central Europe

An agreement between the EU and Ukraine on the partial liberalisation of the carriage of freight by road, which was signed in June 2022, has caused a major transformation of this market. On the one hand, it accelerated the Ukrainian economy’s shift towards the West, which resulted in an increase in Ukraine’s trade with the EU. On the other hand, it contributed to a rapid rise in the quantity of the bilateral carriage of freight by road carried out by Ukrainian freight forwarders. This, in turn, affected the segment of Central European transport companies, which concentrated on handling trade with Eastern European countries.

The protests organised by EU transport companies, which took the form of blockades of important EU–Ukraine border crossing points, often lasting many weeks, are an example of what form the negotiation process regarding this country’s EU accession may take. To avoid further protests, it is necessary for the governments to identify the interests of specific branches of the EU’s economy, devise mechanisms to defuse tensions and to reach difficult compromises, and prepare a system of compensation to be paid to those sectors which will be most affected by the competition from Ukrainian companies.

Accession talks are an optimal instrument to attain these goals. They should formulate a set of requirements for Kyiv to meet, for example as regards the appropriate social standards for drivers (in compliance with the so-called mobility package) in order to restore the rules of equal competition. It is in the Central European states’ vital interest to gain a strong influence on this process. Otherwise, the process of Ukraine’s European integration may transform into a permanent cycle of disputes which could undermine public support in Central Europe for Ukraine’s accession to the EU.

The genesis of the liberalisation of freight carriage by road

On 30 June 2022, as part of an agreement between the EU and Ukraine, a partial liberalisation of freight carriage by road was introduced. This decision was mainly motivated by the war (Russia blocking the Ukrainian Black Sea ports, the closing of air space, granting priority to passenger rail carriage). The European Commission openly declared that its proposal was also intended to facilitate the transport of Ukrainian exports to the EU, which was to be achieved by increasing the number of carriage operations in excess of the limits applied to date[1] (see below). Alongside this, it stipulated that the period of liberalisation should be limited, although it could be extended. It argued that the agreement was in line with the valid legal framework because Ukraine’s association agreement with the EU (DCFTA), which was signed in June 2014, envisages the possibility of liberalising the carriage of goods by road.

To understand the consequences of this liberalisation, it is important to comprehend the rules which govern the international road transportation market. Prior to liberalisation, the carriage of freight from one location to another in two signatory countries, including transit, was subject to strict regulation in the form of quotas. For example, during the annual meetings of a specially formed joint committee, Poland and Ukraine agreed the number of licences for freight forwarders from both states; in 2021 it was 160,000.[2] However, these licenses did not include a further two types of operations, that is cabotage, which involves a foreign carrier transporting cargo between locations in another country, and cross-trade operations, which involve cargo transportation between two locations in two different foreign countries.

The EU–Ukraine agreement has only abolished the requirement for Ukrainian companies to obtain a licence for bilateral carriage. It did not enable Ukrainian transport companies to freely carry out cabotage and cross-trade operations in the EU. The rights to perform cross-trade services are distributed on the basis of multilateral agreements concluded by way of negotiations carried out by the European Conference of Ministers of Transport (ECMT) under the auspices of the International Transport Forum. For example, for 2024 Ukraine obtained around 5,500 annual licences. Each of these authorises one randomly selected vehicle belonging to a company from a specific state to perform, in a given year, an unlimited amount of cross-trade carriage between 43 ECMT[3] member states (this also includes transit to the final destination). Other rules are applied to those EU member states, where the cargo transportation market is almost fully liberalised, and cabotage and cross-trade operations can be carried out by EU freight forwarders without the requirement to hold a relevant licence.

Causes of the increased activity of Ukrainian transport companies

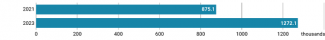

The liberalisation introduced in 2022 has resulted in significant market transformations. As a consequence, 2021–3 saw a major increase (45.3%) in the number of border crossings by trucks. The magnitude of this increase would have been much greater, had Polish transport companies not organised protests. In November and December 2023, the monthly number of border crossings by trucks fell by around a third compared with figures from October.

Chart 1. The number of border crossings by trucks on the border between Poland and Ukraine in 2021 and 2023

Source: the author’s own analysis based on statistics compiled by the Polish Border Guard.

The magnitude of the increase in freight carriage following the Russian invasion has also resulted from both the supply of these services in Ukraine and the demand for this type of transportation. It should be noted that June 2022 saw not only the liberalisation of road carriage, as tariffs and quotas specified in the DCFTA agreement pertaining to Ukraine’s exports were unilaterally lifted for one year (the period of application of the new rules was subsequently extended until 30 June 2024). As a consequence, a rapid acceleration of the process of Ukrainian trade turning westwards was noted. This process has made dynamic progress over the last decade. This resulted in the quick and large-scale inflow of Ukrainian-made goods to the neighbouring countries, including Poland. Since the adopted solutions did not envisage any transition periods, this disrupted these countries’ markets.

Since 2022, we have seen a dynamic increase not only in Ukrainian exports, but also in its imports from EU countries. The reasons include the need to ensure continuous supplies of goods to the Ukrainian market, including fuels. The rise in exports also resulted from the increased sale of Ukrainian-made goods on the Polish market and from the transit of Ukrainian products via the territory of Poland, Slovakia, Hungary and Romania to the Western European markets or, via Polish and Romanian sea ports, to the global market. In 2023, the EU had a 66% share in Ukraine’s exports, and a 53% share of its imports. Poland has played the key part in these statistics, not only because it is Ukraine’s biggest trade partner but also due to the fact that almost 50% of Ukraine’s imports from the EU and 42% of its exports to the EU passes through Poland.[4] Rail transport was unable to fully take over this rapid increase in cargo flows due to its border infrastructure, which was not adjusted to this increased traffic intensity, and in particular to the difference in the rail gauge in Ukraine and in the EU member states (with a few exceptions such as railway line no. 65 running from Hrubieszów to Sławków in the Silesia region, which is operated by PKP Linia Hutnicza Szerokotorowa).

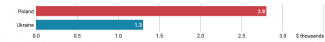

Chart 2. A comparison of the average monthly salary earned by international truck drivers in Poland and Ukraine

Source: author’s own calculation based on Zarobki kierowców zawodowych w Polsce. Rynek pracy w branży TSL, PITD, March 2023, pitd.org.pl and figures compiled by the State Statistics Service of Ukraine, after: Водій-міжнародник: середня зарплата в Україні, work.ua.

An equally dynamic change was recorded for the supply of transport services. After market liberalisation, Ukrainian freight forwarders gained a significant competitive advantage over the companies from Central Europe, mainly resulting from their lower labour cost and exemption from strict EU regulations. The average monthly salary offered to Ukrainian international truck drivers is 45,000–50,000 hryvnias (around $1,200–$1,300), which is much less than the salary earned, for example, by Polish international truck drivers, which is PLN 10,800 ($2,750).[5]

However, it should be noted that competition posed by Ukrainian companies (at least at present) is limited and affects only around 1,000 Polish transport companies (out of more than 100,000 companies operating in this sector). The majority of the Polish freight forwarding sector focuses on operating on the Western markets, whereas the group of companies which provide their transport services on the Eastern markets forms a small, although important, niche. According to Eurostat data, for example in 2021 Russia’s share in the services provided by the Polish freight forwarding sector was 1.5% in imports and 1.7% in exports.

Chart 3. A comparison of the number of tractor units in Poland and in Ukraine prior to the Russian invasion

Source: author’s own calculation based on figures published by Statistics Poland and by the former Ukrainian Ministry of Infrastructure.

In Ukraine, the road transportation sector’s importance for the country’s economy is incomparably smaller than for example in Poland. Before the war, around 43,000 tractor units were registered in Ukraine (according to statistics compiled by the former Ukrainian ministry of infrastructure), whereas in Poland in 2021 their number was estimated at more than 500,000 (according to Statistics Poland). However, the situation is rapidly changing because Ukraine has taken note of the window of opportunity which its transport sector is facing. As a consequence, numerous new businesses emerged there, whose owners began to buy sometimes very old tractor units and trailers in order to offer road transport services. Investors from Western Europe have also begun to incorporate freight forwarding companies on the Ukrainian market. Moreover, numerous Ukrainian freight forwarders, who have lost their opportunities to provide transport services on the Belarusian and Russian markets, have now moved to the Western markets. The last two years have seen a surge in the export of tractor units and trailers from Poland to Ukraine. In 2023, it increased by 65% (compared with the already very significant figures recorded in 2022), and its value stood at PLN 591 mn. At present, the estimated number of tractor units registered in Ukraine is around 50,000.

The consequences of the liberalisation for the region’s transportation sector

In 2021, Polish and Ukrainian carriers obtained an equal number of licences for bilateral transportation operations (100,000) and for transit operations (60,000). However, there was a significant difference in how these licences were used. Ukrainian freight forwarders used up almost 100% of their licences, whereas the Polish ones used just 35–40%. Since the number of Ukrainian licences to carry out transportation operations to handle trade between Ukraine and the EU was insufficient, a significant amount of carriage was performed by Polish companies, despite their higher prices.

Chart 4. The share of Polish carriers in transportation operations between Poland and Ukraine in 2021 and 2023

Source: author’s own analysis based on figures compiled by the Ministry of Infrastructure of the Republic of Poland.

Following the June 2022 liberalisation, the situation changed. According to statistics published by the Polish Border Guard, the share of Polish companies in transportation operations between Poland and Ukraine fell from 38% in 2021 to 8% in 2023. This decrease was not only due to the Polish carriers’ less competitive prices. Numerous carriers were unable to provide their services on the Ukrainian market due to safety concerns, difficulties with obtaining insurance for their vehicles and cargo, and to controversy linked with the operation of the Ukrainian electronic border queue system known as eQueue (eCherha). Organisations grouping Polish road carriers for example highlighted the problem of this system being non-transparent, as in their view it has failed to eliminate the practice of corruption on the border. The Ukrainian side, for its part, has accused the Central European freight forwarders of abusing the eQueue by repeatedly registering in the system in order to accelerate their clearance.

Increased competition on the part of Ukrainian carriers coincided with a slump in the EU’s economic situation, which resulted, among other things, from the rise in the inflation rate and in energy prices. According to the TIMOCOM logistics services marketplace, in 2023 the number of freight offers fell by 30%, including by as much as 40% in Germany alone. In the Polish road transportation sector, which generates revenues of PLN 190 bn, employs 500,000 individuals and handles 20% of the EU’s carriage operations, the sentiment is increasingly negative. A report published by the Transport i Logistyka Polska organisation indicates that as many as 48% of freight forwarding companies are expecting a decline in their revenues in the coming two years.[6] Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, cabotage and cross-trade operations were the driving force of this sector, while at present domestic operations are more important. The change brought about due to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has particularly affected the transport market segment which handled trade with the eastern partners. This is because it not only lost its opportunity to serve the Belarusian and Russian markets, but also it experienced the negative consequences of the increased competition posed by Ukrainian companies.

Protests in the region’s states

Increased competition on the part of Ukrainian carriers has sparked concern in the Central European transportation sector. Following the region states’ accession to the EU, freight forwarders from these countries gained a strong position on the European road transportation market. At present, this sector generates a value-added of 4–6% to the GDP of the individual states of the region, and in the case of Poland, Slovakia, Hungary and Romania is also an important source of their trade surplus. The expansion of Central European carriers was so fast that the Western European states pushed through the introduction of the so-called mobility package, which in 2020–26 imposes gradual limitations on the provision of cabotage and cross-trade transportation operations. Thus, the sector was sceptical about the liberalisation of the EU–Ukraine carriage, and at present, when it is facing an economic slump, it has become particularly sensitive to the potential threat posed by Ukrainian freight forwarders performing cabotage and cross-trade transportation operations from which they have so far been banned.

Thus far, the biggest road carrier protests have occurred in Poland, where between 6 November 2023 and 16 January 2024 representatives of these companies blocked border crossing points between Poland and Ukraine. Their demands included a return to the system of granting licences, a ban on Poland issuing carriage licences to companies with non-EU capital, the establishment of separate tracks in the Ukrainian eQueue (an obligatory electronic system for trucks which enables their customs and border clearance) for vehicles with EU licence plates and for those which have no cargo.

As regards Slovakia, in a gesture of solidarity with the Polish transport sector, one Slovak carrier association blocked the border with Ukraine, first on 16 November 2023 and then on 1–4 December. Its main demand was a return to the practice of issuing licences to Ukrainian freight forwarders. In addition, Slovak associations organised coordination meetings with their counterparts from other Central European states. The Robert Fico government has demonstrated that it understands the demands voiced by the Slovak carriers. It has promised to step up inspections of Ukrainian trucks and to endeavour to have the system of issuing road carriage licences to Ukrainian carriers reinstated by 30 June 2024, when the decision will need to be made regarding the potential extension of the liberalisation.

The situation is very similar in Hungary, where the transport sector is protesting against what it views as the practice of Ukrainian carriers illegally carrying out cabotage operations. It is also demanding a return to the licence system.[7] Starting from 11 December 2023, for ten days blockades of the border with Ukraine were set up (in the vicinity of the village of Győröcske). In response to these developments, the Hungarian government devised a package of solutions to support the Hungarian transport sector (it became valid on 28 January 2024). The main instruments include the introduction of a minimum fee for a transport service, the loading and sorting of pallets, as well as parking fees, and the reduction in the number of sub-contractors involved in performing transport operations. Other solutions are being prepared, including the plan to reduce the bureaucratic burden shouldered by Hungarian carriers and to offer compensations for some excise duties.

Also in Romania, in January a three-week protest of the transport industry was held. This involved blockades of the main highways, ring roads and, temporarily, some border crossing points with Ukraine. Unlike in other states of the region, Romanian carriers mainly highlighted the instances of representatives of the Romanian border services favouring the Ukrainian drivers. Allegedly, representatives of these services were more lenient during inspections of Ukrainian trucks (for example when it was discovered that the vehicle’s weight with cargo was in excess of the specified limit or when the vehicle’s state of repair was insufficient). Romanian carriers also complained about problems with access to the country’s ports. As a result of a compromise reached with the protesters, the authorities decided to offer compensation for a portion of the excise duty and to reduce the cost of vehicle insurance.

The tension over the liberalisation of freight carriage by road was least intensive in the Czech Republic. Although the Czech transport sector has expressed its increasing concern about the expansion of Ukrainian carriers, the magnitude of the problem is not great because this country does not border Ukraine and in the Czech Republic the freight forwarding sector is not as significant as it is in other states of the region.

The prevailing sentiment among the region’s road carriers is their feeling of injustice linked with the fact that they had to bear a considerable cost of adjusting to the competition on the EU market. At present, they do not trust the Ukrainian freight forwarders and suspect them, in the situation of an economic decline, of carrying out cross-trade operations, especially cabotage, by performing jobs obtained via transport bidding platforms. Industry associations argue that the absence of an effective system of supervision of cabotage and cross-trade operations may encourage some Ukrainian carriers to enter Poland unladen and then perform these operations in the EU illegally.

Searching for a long-term solution

An acceleration in the westward shift of Ukrainian trade is a consequence of the Russian invasion and is also the only way to sustain the operation of the Ukrainian economy. Experience gained in recent months clearly shows that while it remains uncontrolled and does not envisage compensation mechanisms, the liberalisation of the EU’s freight carriage by road and trade with Ukraine will spark increasing protest from consecutive sectors of the Central European economy, which have complained about unfair competition. It seems that without slowing down and organising this process, the level of support for Ukraine’s accession to the EU may begin to erode in the region’s states.

Accession talks should serve as a key mechanism to resolve all such disputes. This is because they will set a number of commitments for Ukraine to fulfil in order to be allowed to become a fully-fledged EU member state without undermining the single market’s cohesion. For the Central European states, it will be important to create a relevant platform for influencing the talks, especially their third chapter regarding competitiveness and inclusive growth. To be able to speak in a strong voice during these negotiations, it is necessary to properly define common interests and to agree specific proposals to prevent abuse and to ensure equal operating conditions on the EU market (known as the level-playing field). For example, the Central European transportation industry will find it difficult to accept that it needs to fulfil the commitments resulting from the so-called mobility package, while its Ukrainian competitors are exempt from it.

It is also important to convince freight forwarders from Central Europe that there have been no violations of the EU–Ukraine agreement involving Ukrainian carriers carrying out cabotage and cross-trade operations without the relevant licences. It seems that to properly monitor the cabotage operations it would be sufficient to bolster the national inspection bodies (road traffic inspection as well as labour inspection which is authorised to check the working conditions of drivers who are subject to worker posting regulations) and to ensure the cargo tracking systems are functioning correctly. To supervise the cross-trade operations, it will be necessary to step up cooperation regarding data exchange in the EU. In addition, due to the fact that the Central European carriers have not been offered any transition period to adjust to the market transformation, it seems justified that they should be offered certain solutions in the form of compensation, especially given that there are sectors which have profited significantly from the liberalisation of trade with Ukraine. This decision could involve compensating them for the losses they have suffered in previous years. Another proposed solution would involve enacting a law to commit Polish principals to ensure that a specific number of transport operations to Ukraine are performed by Polish road transport companies.

Despite the problems resulting from liberalisation, at present trade between some Central European states and Ukraine is highly positive. For example, in 2023 Poland’s exports to Ukraine totalled PLN 51.6 bn, up 13.4%, while its imports were PLN 20.3 bn, down 28%. This indicates that in 2023 the Ukrainian market generated a trade surplus for Poland of PLN 31.3 bn (the fifth biggest result among Poland’s trade partners). This demonstrates the magnitude of the potential faced by Central Europe, which is linked with the prospective resolution of contentious issues in the region’s relations with Ukraine. In the long term, this country could be an important market for Central European producers selling their moderately technologically advanced industrial products and weapons.

[1] Proposal for a Council Decision on the conclusion, on behalf of the European Union, of the Agreement between the European Union and Ukraine on the carriage of freight by road, COM(2022) 308 final, European Commission, 17 June 2022, eur-lex.europa.eu.

[2] Protokół z posiedzenia polsko-ukraińskiej Komisji Mieszanej ds. międzynarodowych przewozów drogowych, Lviv, 3–4 August 2021, gov.pl.

[3] ECMT Road Transport Platform, International Transport Forum, itf-oecd.org.

[4] S. Matuszak, ‘A key partner. Ukraine–EU trade in 2023’, OSW, 4 March 2024, osw.waw.pl.

[5] Zarobki kierowców zawodowych w Polsce. Rynek pracy w branży TSL, PITD, March 2023, pitd.org.

[6] Transport drogowy w Polsce 2023, Transport i Logistyka Polska, SpotData, July 2023, tlp.org.pl.

[7] It is difficult to assess the credibility of the presented accusations because, with no licencing system, it is not easy for representatives of road traffic inspection to prove that a specific carrier is illegally performing cabotage operations and in particular cross-trade operations, especially in a foreign country. However, Ukrainian freight forwarders can easily obtain these jobs from transport bidding platforms, which significantly increases their revenue from carriage operations. Moreover, in many countries the penalties for illegally carrying out such carriage operations are relatively small compared to the potential profits.