Crisis as an opportunity. A new stage in EU-Central Asia relations

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has changed the European Union’s approach to Central Asia (Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan). Over the last two years, it has become more important for the EU to maintain this region’s stability and harness its potential in energy and transportation. During this period, both sides have developed a model of regular political contacts at the highest level, updated their strategy for cooperation and launched new economic projects. These moves have been reinforced by complementary steps of the EU’s individual member states, mainly Germany and France. EU-Central Asia relations have been deepening despite the EU’s consistent criticism of the authoritarian nature of Central Asian governments.

These closer relations have presented the Central Asian states with an opportunity to avoid marginalisation in the wake of the war in Ukraine. They have perceived this as an attractive initiative in economic terms and, to some extent, in political terms, as a way of strengthening the region. Cooperation with the EU has complemented, but not replaced or undermined, Central Asia’s strong ties with Russia and China. These two countries have made it clear that they want to maintain their dominance over this region, but so far they have not made any clearly hostile moves against the EU’s cooperation projects and have even recognised some aspects of these projects as beneficial to themselves.

Under the current conditions, there is scope for the EU and the Central Asian states to further deepen their cooperation. This will depend on international developments, including the outcome of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the level of determination of the EU and the regional countries, and on Russia’s and China’s decisions on whether to maintain their restrained attitude.

Central Asia in EU policy to 2022

Despite the firm diplomatic basis, the dynamic of political relations between the EU and the five Central Asian states over the past two decades has been relatively low.[1] In a step aimed at revitalising the EU’s course, in 2019 the Council of the EU adopted a new strategy towards the region,[2] which described the nature of mutual relations as a “non-exclusive partnership.” This indicated that the EU was searching for an idea for this region but was also reluctant to compete with China and Russia there.

The strategy defined three broad areas of the EU’s interest: resilience (promoting democracy, strengthening border and migration management, protecting the environment and managing water resources), prosperity (supporting economic reforms, intra- and inter-regional trade and investment, promoting sustainable connectivity) and regional cooperation (strengthening partnerships between civil societies and parliaments, raising the EU’s profile in the region). After the EU adopted this document, the scope of mutual consultation was extended to include formats on civil society and trade.

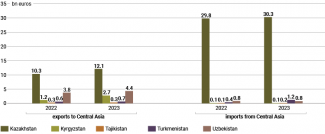

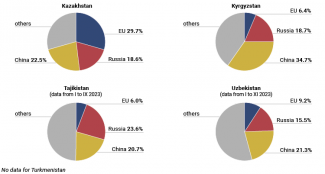

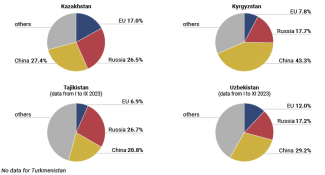

Until 2022, the EU-Central Asia Ministerial Meetings (at the level of the EU High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy and the foreign ministers of individual countries) were the main forum of political dialogue between the EU and the Central Asian states.[3] The economic and trade agreements that these countries concluded with the EU were not expanded, which largely stemmed from their failure to make any progress on democratisation. It was not until 2020 that the Enhanced Partnership and Cooperation Agreement (EPCA) with Kazakhstan come into force, and this is the EU’s only such agreement in this part of the world to date. The Central Asian states were insignificant trading partners for the EU. The EU’s member states markets are the main export destination for Kazakhstan (largely due to oil sales), but this country was down in 29th place in the ranking of the EU’s trade partners in 2022.[4] At the same time, the EU has long been one of Central Asia’s three largest partners alongside China and Russia (see charts below) as well as the largest investor and provider of development assistance to this region.

Chart 1. The value of the EU’s and Central Asian countries’ exports/imports in 2022-23

Source: author’s own compilation based on data from Eurostat.

Chart 2. The share of the Central Asian countries’ trade with the EU, Russia and China in the structure of their foreign trade in 2023

Source: author’s own compilation based on data from the state statistical offices of the Central Asian countries (including a correction from the National Bank of Tajikistan).

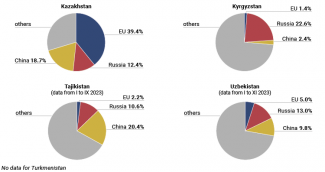

Chart 3. The share of exports to the EU, Russia and China in the Central Asian countries’ structure of exports in 2023

Source: author’s own compilation based on data from the state statistical offices of the Central Asian countries (including a correction from the National Bank of Tajikistan).

Chart 4. The share of imports from the EU, Russia and China in the Central Asian countries’ structure of imports in 2023

Source: author’s own compilation based on data from the state statistical offices of the Central Asian countries (including a correction from the National Bank of Tajikistan).

In a major development, Central Asia was included in the Global Gateway strategy that the EU launched in December 2021 with the aim of supporting investment projects in the area of connectivity, which encompasses transport, and digital and energy links based on the principles of the European Green Deal.

The EU’s new approach: more interests, more relevance

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine prompted the EU to significantly increase its activity in the post-Soviet area.[5] Among the Central Asian states, the Russian assault in February 2022 sparked concerns about their own sovereignty and opened a ‘window of opportunity’ for drawing closer to the EU. The main stated motives of the EU’s policy in Central Asia include its concern for the region’s stability and a desire to obtain greater influence over the processes taking place there.[6] At the same time, the EU has been seeking to expand its cooperation with these countries in the area of raw materials and energy in a bid to find alternative suppliers to Russia.

These plans have been reflected in intensive political dialogue (including visits by high-ranking EU politicians), in efforts to find optimal forms of cooperation and in the launches of new projects. Over time, it has become an important goal for the EU to convince the Central Asian states to comply with its sanctions regime against Russia, as Central Asia is a convenient channel for circumventing these restrictions. The EU has also been working with these countries to develop transport initiatives bypassing Russia.

Almost two years of work on a new approach to the region culminated in October 2023 when the Council of the European Union adopted the Joint Roadmap for Deepening Ties between the EU and Central Asia, which envisages enhanced cooperation in five key areas (see Appendix).[7] In fact, it is an update to the 2019 strategy that reflects the interests of both sides. Before it was drafted, the EU and Central Asia had raised their political dialogue to a higher level. Notably, they held two unprecedented ‘high-level meetings’ with the participation of the President of the European Council, Charles Michel, and most of the region’s leaders.

Economic issues, which are strongly linked to energy, climate/environmental and transport cooperation, feature prominently in the Joint Roadmap. At present, they can be regarded as the most important aspects of mutual relations, and may also be considered as the forward-oriented ‘vehicles’ of EU-Central Asia cooperation. The ties in these areas are those which have been strengthened the most. In November 2022, the EU launched two flagship initiatives for Central Asia as part of the Global Gateway: the Team Europe Initiative on Water, Energy and Climate and the Team Europe Initiative on Digital Connectivity.

In another important step, in late January 2024 the EU committed to provide €10 billion using various financial instruments to develop the Trans-Caspian International Transport Route (TITR, the so-called Middle Corridor), which connects Europe to China via Central Asia, the Caspian Sea and the Caucasus or Turkey, bypassing Russia.[8] In November 2022, the EU signed an agreement with Kazakhstan on a strategic partnership in the area of critical raw materials, batteries and renewable hydrogen; more recently, in April 2024, it reached a similar agreement with Uzbekistan in the field of critical raw materials. These steps have been part of the EU’s efforts to implement its Action Plan on Critical Raw Materials, which was adopted in 2020.

The EU’s objectives for Central Asia are in keeping with the interests and policies of its prominent members, mainly Germany and France. In particular, Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan have become more important for these countries as sources of raw material supplies. Shipments of Kazakh oil to Germany via the Druzhba pipeline have begun under a contract that was signed in June 2023; 993,000 tonnes of crude had been delivered along this route by the end of last year. Kazakhstan has also strengthened its position as one of the three largest exporters of oil to France, shipping 5.47 million tonnes there last year. France has also been increasing its imports of uranium from Central Asia under agreements from 2023. In fact, even in 2022, more than 50% of uranium supplies to the French market came from Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan.[9] Investments in renewable energy sources, such as the German-Swedish Svevind Energy Group’s $50bn wind and solar power plant in Kazakhstan and the France's TotalEnergies SE’s $1.4bn wind energy complex (also in Kazakhstan) are another important component of these bilateral relations.

Cooperation with the EU as leverage for the region?

The Central Asian states, especially Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, have taken the risk of broadening their cooperation with the EU. Their political dialogue with Brussels has moved to a higher level. In addition to regular meetings with the President of the European Council in the region and visits by the leaders of Germany and France, this has been reflected in visits by the Kazakh and Uzbek presidents to Paris and Berlin for the Germany-Central Asia summit along with the three other Central Asian leaders.[10] This has resulted in closer regional political coordination, since the EU, as is the case with the US and China, prefers to hold meetings with all the five countries at the same time. Both in their joint activities and diplomatic relations with the EU, the Central Asian states have avoided making any commitments or moves that would explicitly target Russia (with the exception of declarations to comply with the sanctions) or China. For Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan, where government repression has increased the most over the past two years, cooperation with Russia and China is clearly a priority. They have focused on selective cooperation with the EU: Kyrgyzstan has sought to ensure that it will not be subjected to sanctions and has made efforts to boost trade, while Tajikistan has focused on absorbing development funds and protecting its borders.

Over the past two years, the Central Asian states have been determined to develop their economic ties with the EU. They have been working to build their credibility as suppliers of raw materials amid global changes in this market. In the energy sector, Kazakhstan has secured agreement from the EU to exclude the exports of goods and services for the maintenance and operation of the Caspian Pipeline Consortium’s (CPC) oil pipeline from its sanctions regime. This piece of infrastructure connects Kazakhstan’s oil fields to Russia’s Novorossiysk terminal on the Black Sea and acts as a pillar of the Kazakh economy: 80% of its production headed abroad is shipped through this pipeline.[11] Kazakhstan has also started supplying oil to Germany via the Druzhba pipeline.[12] Moreover, it has improved its position as a supplier of crude to the European markets, primarily France, Romania and Italy (in late 2023, it was the third largest seller of oil to the EU).[13] The isolationist Turkmenistan, for its part, has been exploring the possibility of exporting gas to the EU, but it appears that it will be unable to actually start supplies any time soon. Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan have consolidated their position as key suppliers of uranium to France by expanding their cooperation in the extraction and export of uranium.

The Central Asian states are interested in obtaining greater preferences in trade with the EU. For example, Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan have been seeking to expand their bilateral trade agreements. The countries of Central Asia have also offered their political support for the transport initiatives they have been developing in cooperation with the EU (such as those around the Middle Corridor). These form part of the EU’s efforts to build alternative transport links to routes running through Russia. From the Central Asian perspective, projects of this kind are raising the region’s attractiveness for trade and investment and speeding up the development of both hard (ports, railways, roads) and soft (for example, in the area of digitisation) infrastructure. Kazakhstan, the most determined country in this regard, has managed to secure China’s support for the Middle Corridor.[14] Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan have been seeking to expand their cross-border cooperation with Kazakhstan with a view to benefiting from the development of this route, the main part of which runs entirely through the Kazakh territory. At the same time, the two countries, as well as Turkmenistan, have been striving to develop their own infrastructure. This includes efforts to build the China-Kyrgyzstan-Uzbekistan railway, and investments in the port of Türkmenbaşy.

Russia and China's reaction to the EU’s stepped-up activity: making a counter offer and leveraging their advantages

Russia and China have interpreted the EU’s growing ambitions in the region since February 2022 as a challenge. The EU’s stepped-up activity, both political and economic (notably in the energy sector), could potentially undermine their interests. Therefore, at first they jointly signalled their aversion to the EU’s, and more broadly the West’s, reinvigorated engagement in Central Asia. However, as the situation unfolded, they came to see these moves as a development that does not undermine their strategic role. In some areas, such as transport and trade, this cooperation has even indirectly benefited them.

In the political dimension, the Kremlin initially responded to the Central Asian countries’ moves towards closer ties with the EU by putting pressure on them, especially Kazakhstan. An example of this was Russia halting shipments of Kazakh oil via the CPC pipeline on four occasions in 2022. It subsequently reduced its pressure under China’s influence. At the September 2022 summit of the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation in Samarkand, China expressed its support for the Central Asian countries’ sovereignty and territorial integrity while also reaffirming the sustainability of its cooperation with Russia and the existing order in the region, with China and Russia as the dominant actors.

Russia and China stressed their willingness to strengthen their coordination in this part of the world even more strongly in a statement after Xi Jinping’s visit to Moscow in March 2023. In reality, however, they have not exerted heavy pressure on the region to inhibit its cooperation with the EU. They have instead adjusted their own course towards it and updated their economic offer for the Central Asian states. As part of these efforts, Russia and China held summits with these countries at a formally higher level than the EU’s ‘high-level meetings’.[15]

In the energy dimension, even though the region has expanded its cooperation with the EU, the entrenched interests of Russia and China have not been directly affected. For example, projects have not been launched that would permanently bind the EU to Central Asia, such as gas exports from Turkmen deposits via the Caspian Sea to Europe. Moreover, during this period, Russia has strengthened its gas relations with Uzbekistan as a consumer and with Kazakhstan as a transit state under an agreement from June 2023. This process has followed new patterns: the usual direction of supplies has been reversed and, most importantly, Russia has sought to win contracts by acting as a constructive partner that takes into account the interests of both sides rather than negotiating from a position of strength. In this context, the Central Asian countries rejected the Kremlin’s initial offer that would give it access to the local transmission infrastructure (the Central Asia-China gas pipeline). Indeed, they did so out of fear of losing control of this route, which carries Turkmen, Kazakh and Uzbek gas to China.[16] At the same time, Russia has retained the option of effectively stopping Kazakh oil exports via the CPC pipeline to the Novorossiysk terminal and onwards to the west. The rising sales of Kazakh crude to the EU (from 36.7 million tonnes in 2022 to 44.3 million tonnes a year later) have deepened Kazakhstan’s dependence on Russian infrastructure.[17]

At this stage, neither Russia nor China has come to see the EU’s transport ambitions in the region as a direct threat. For China, Central Asia’s largest trading partner, the development of transport corridors and infrastructure between this region and Europe aligns with its interests; for example, it expressed its support for the Trans-Caspian International Transport Route at the Belt and Road Forum in October 2023. For Russia, the new trade routes offer an opportunity to gain access to sanctioned goods through this region.

China and Russia have adopted a cautious, wait-and-see approach concerning the intensifying cooperation between Central Asia and the EU. China in particular sought an effective way to boost its own attractiveness in the region and to leverage its advantages that stem from its existing engagement in Central Asia and geographical proximity. At the same time, we can assume that the current approach which both China and Russia are taking regarding closer links between the EU and Central Asia is temporary and that they have retained the option of blocking these ties as an important instrument at their disposal.

Conclusions and prospects

As a result of the war in Ukraine, Central Asia has become more important for the EU. The change in the EU’s course on this region can be seen in the bloc’s political engagement, stated objectives and new initiatives. This is part of the EU’s broader effort to step up its activity in the post-Soviet area. Its priorities include maintaining stability in this area, developing effective political dialogue and pursuing transport and energy cooperation. France and Germany have supported this attitude through actions motivated by their own economic interests.

Closer relations with the EU have presented the Central Asian states with an opportunity to strengthen their own sovereignty and speed up modernisation. This is important for Kazakhstan as well as the other Central Asian countries which are in the early stages of economic reform, notably Uzbekistan. They are focused on reaping both the immediate benefits (trade) and the strategic benefits (diversification of markets and transport routes, access to technology) of this opportunity. Turkmenistan, for its part, has pursued more active gas diplomacy with the EU. This marks a significant shift in the approach of Central Asia’s most authoritarian state, which has previously firmly isolated itself from the international arena. Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan have been less engaged in cooperation with the EU, which shows the asymmetry in this field among the Central Asian states.

In the foreseeable future, Central Asia’s relations with the EU will not undermine Russia’s or China’s position in the region, especially in the security dimension.[18] However, closer ties between Central Asia and the EU have generated challenges for Russia and China and driven them to make their offer to the region more attractive. Paradoxically, Central Asia’s rising importance, partly stimulated by the EU’s policy, is one of the factors that have contributed to its present stability.

The last two years have shown that ties between Central Asia and the EU can develop despite the existence of authoritarian regimes in Central Asia and severe international tensions that have affected the policies of individual countries and the EU. The prospects for and importance of this cooperation will be determined by the outcome of the war in Ukraine, the degree of stability in the region and in the South Caucasus (which links the EU and Central Asia), and also by the West’s future relations with Russia and China. Another important factor is whether the EU will change its course after this year’s elections to the European Parliament; in particular regarding whether the EU’s institutions will be willing to continue this active policy and potentially develop a new strategy towards this region.

It is unlikely that relations with the EU will become a priority for Central Asia. Therefore, it is even more unlikely that Central Asia will emerge as a significant focus of the EU’s foreign policy. Contacts between the two sides will still be based on energy, trade and transport as the main areas of cooperation. Nevertheless, as these ties continue to deepen, the EU’s importance for Central Asia will grow due to the associated benefits for the region’s modernisation and economy.

APPENDIX

The main areas of cooperation between the EU and Central Asia under the Joint Roadmap

The intensification of political dialogue includes steps to raise the profile of this relationship and consolidate it at the highest level. The best example of this is the ‘high-level meetings’ with the participation of President of the European Council Charles Michel and the Central Asian leaders. The first such meeting took place on 27 October 2022 in Astana, followed by another gathering on 2 June 2023 in Cholpon-Ata, Kyrgyzstan. The first EU-Central Asia Summit was scheduled to take place in Uzbekistan in 2024.

The two sides aim to strengthen their economic ties by consolidating the EU-Central Asia Economic Forum (which has existed since 2021 and was last held in May 2023) and by expanding their trade and political agreements. The EU concluded negotiations on the Enhanced Partnership and Cooperation Agreement (EPCA) with Kyrgyzstan in July 2019 and with Uzbekistan three years later; however, it has failed to ratify either of them. It launched talks on the EPCA with Tajikistan in February 2023.

Cooperation is being pursued under the Global Gateway strategy in the areas of: energy, climate/the environment and transport. The impetus for developing these ties came from the first EU-Central Asia Connectivity Conference that was held in Samarkand in November 2022. At the European Commission’s request, the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development also produced a study entitled ‘Sustainable transport connections between Europe and Central Asia‘, which was published in June 2023. The aforementioned inaugural Investors Forum for EU-Central Asia Transport Connectivity took place in January 2024.

In the area of security, the EU’s longest-running programmes for Central Asia (launched in 2003), the Border Management Programme in Central Asia (BOMCA) and the Central Asian Drug Action Programme (CADAP), form the basis for further cooperation. These two initiatives relate to border protection and measures to counter drug trafficking. The EU has also made it possible to provide the Central Asian states with expertise on hybrid threats and to include them in training conducted by the European Security and Defence College (ESDC).

The EU considers the development of the EU-Central Asia Civil Society Forum (which has functioned since 2019) to have played a significant role in the improvement of people-to-people relations and mobility, alongside its own training and education programmes, Horizon Europe and Erasmus+. The EU has announced that it will expand its educational and scholarship opportunities for independent researchers from the region as well as its training for Central Asian diplomats.

[1] The EU has delegations in all the Central Asian countries. Its first delegation in the region was opened in Kazakhstan in 1999, and the last one in Turkmenistan in 2019. The EU Special Representative for Central Asia, who reports to the EU High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, was appointed in 2005.

[2] ‘The EU and Central Asia: New Opportunities for a Stronger Partnership’, The European Commission, 15 May 2019, eeas.europa.eu. The previous strategy from 2007, which was updated several times, prioritised a securitised approach to the region. See The European Union and Central Asia: The New Partnership in action, The European Commission, June 2009, eeas.europa.eu.

[3] The 19th meeting in this format took place in October 2023. For the first time ever, the foreign ministers of all the EU member states attended it, which signalled their willingness to strengthen relations with the region. A lower-level format called the High-Level Political and Security Dialogue was launched in 2013. Meetings of the Cooperation Councils between the EU and the individual countries play a consultative role in the bloc's relations with four of the Central Asian states; the EU and Turkmenistan hold meetings of the Joint Committee.

[4] ‘European Union, Trade in goods with Kazakhstan’, The European Commission, Directorate-General for Trade, 19 April 2023, ec.europa.eu.

[5] In addition to support for Ukraine and Moldova, this includes the EU's involvement in political and security issues in the South Caucasus, notably the conflict between Azerbaijan and Armenia.

[6] The European Parliament also called for greater activity in this region in its overview resolution of 17 January 2024. See ‘European Parliament resolution of 17 January 2024 on the EU strategy on Central Asia’, europarl.europa.eu.

[7] ‘Joint Roadmap for Deepening Ties between the EU and Central Asia’, The Council of the EU, 23 October 2023, eeas.europa.eu.

[8] At the Investors Forum for EU-Central Asia Transport Connectivity in Brussels on 29-30 January 2024, the European Investment Bank concluded agreements to provide Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan with €1.47 billion in loans guaranteed by the European Commission. Moreover, the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development signed a preliminary agreement with Kazakhstan to finance projects in this country worth €1.5 billion.

[9] M. Popławski, ‘Macron in Central Asia: the rise of French ambitions in the region’, OSW, 13 November 2023, osw.waw.pl.

[10] L. Gibadło, M. Popławski, ‘The ‘Central Asian Five’ in Berlin: time for a strategic partnership’, OSW, 5 October 2023, osw.waw.pl.

[11] I. Wiśniewska, ‘Tightening restrictions: the EU’s eleventh package of sanctions against Russia’, OSW, 26 June 2023, osw.waw.pl.

[12] M. Kędzierski, ‘Kazakhstan is set to supply oil to Germany’, OSW, 23 June 2023, osw.waw.pl.

[13] O. Tonkonog, ‘Germany wants Kazakhstan to double its oil exports’, Курсив, 19 February 2024, kz.kursiv.media. Italy is the main buyer of Kazakh oil, but almost all of it is then shipped to southern Germany, Austria and the Czech Republic. P. Sorbello, ‘Italy Is Not Kazakhstan’s Main Oil Destination, Data Shows’, Власть, 18 January 2024, vlast.kz.

[14] K. Popławski et al., ‘The Middle Corridor. A Eurasian alternative to Russia’, OSW, Warsaw 2024, osw.waw.pl.

[15] On 14 October 2022, the first ever Russia-Central Asia Summit was held in Astana with Vladimir Putin in attendance. On 18-19 May 2023, China organised the China-Central Asia leaders' summit in Xi'an.

[16] M. Popławski, F. Rudnik, ‘Russian gas in Central Asia: a plan to deepen dependence’, OSW, 31 October 2023, osw.waw.pl.

[17] G. Cretti, L. van Schaik, ‘Resource curse or darling. Rethinking EU energy interests in Kazakhstan’, Clingendael Policy Brief, March 2024, pp. 3–4, clingendael.org.

[18] Russia increased its 'assets' in this area after the Kyrgyz parliament ratified an agreement to build a joint air defence system with Russia in October 2023.