Budanov’s sanctions. The consequences of Ukrainian attacks on Russian refineries

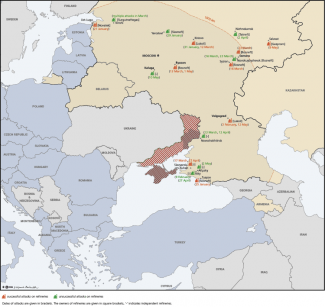

Ukrainian drone strikes on refinery facilities inside Russia have dealt a significant blow to the Russian fuel sector. During the first four months of 2024, the Ukrainian forces attacked more than a dozen refineries; damage of varying degrees was reported at eight of these. As a result, Russian plants temporarily shut down some of their processing capacity, which led to a drop in fuel production.

Despite the US administration’s fears that the global oil and fuel market could be destabilised, the price dynamic for both categories of commodities to date does not suggest that the Ukrainian strikes have driven prices up. On the contrary, the need to reduce processing and the impossibility of storing crude have forced Russian exporters to increase exports. At the same time, the refinery shutdowns have driven down sales of petroleum products abroad, resulting in losses primarily for Russian companies.

The Ukrainian attacks and the resulting drop in fuel production have created a number of challenges for the Kremlin, including the need to deal with logistical tensions, strengthen air defence and increase imports of petroleum products. Given the political importance of fuel availability, reduced processing has forced the Russian government to use tools of intervention in order to ensure that the market is adequately saturated. For example, it has forced the fuel sector to redirect supplies onto the domestic market at the expense of the foreign markets. Should the Ukrainian strikes continue and cause more temporary shutdowns at refineries, the government will probably have to step up its intervention, and that will generate costs for the state and may lead to market imbalances.

The scale of the destruction

Since the start of Russia’s full-scale invasion, the Ukrainian side has conducted strikes against facilities associated with Russia’s oil and fuel sector, including fuel depots, pipeline infrastructure and refining plants. As of last autumn, Ukraine has stepped up its attacks on refineries and expanded the range of its drone strikes. It has carried out a series of successful attacks on plants in European Russia: eight of these facilities have suffered damage that forced them to shut down some of their processing capacity. The most extensive damage was reported last March (see Appendix).

As a result of these attacks, some of the country’s refining capacity has been shut down. Depending on estimates, primary oil processing has fallen by 500,000–900,000 bbl/d[1] of capacity, or 8–14% of Russian plants’ total production. The real duration of the shutdowns has varied depending on the type of facility, its role, and above all the scale of damage. In some cases, refineries resumed operations the day after the strike; in others, it took weeks or even months before production resumed.

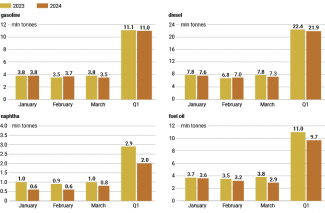

The Ukrainian airstrikes have thus caused a drop in crude processing at Russian refineries: from the start of the year to April, its rate fell from 5.5 to 5.2 million bbl/d, or more than 5%, hitting its lowest level in nearly a year. The effects of shutdowns at plants can also be seen in the structure of fuel production. In March, the month which saw the heaviest attacks, the production volumes decreased in each of the four categories of petroleum products. This occurred despite the fact that production usually picks up in this period ahead of maintenance work in May.

In the case of gasoline and diesel, the falls in March were 7.9% and 6.4% y/y respectively; it is worth noting here that the production dynamic did not fall in the first quarter of last year. The biggest drop was recorded in fuel oil production. This may suggest that the production volume of this product was deliberately reduced with the aim of preventing diesel shortages at petrol stations. Diesel oil is produced through a similar process to fuel oil; thus, some refineries were able to increase diesel production at the expense of fuel oil.

Chart 1. Crude oil processing at Russian refineries from February 2022 to April 2024

Source: Bloomberg.

Chart 2. Production of petroleum products in Russia by month in Q1 2023 and 2024

Source: Rosstat.

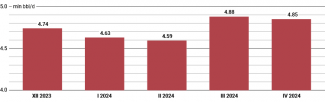

The damage to the refineries was also reflected in Russia’s structure of exports, for both fuel and crude oil. At the same time, no significant drop in oil production was reported. In a situation of limited refining, Russia was able to maintain its existing levels of production by increasing its sales of crude abroad.[2]

In March, Russian exports of crude oil hit their highest level in ten months at nearly 4.9 million bbl/d, up more than 5% on the volume in February. This rise came even though in early March Russia announced that it would reduce crude production and foreign sales as part of the OPEC+ cartel:[3] it committed to reduce production voluntarily by 350,000 bbl/d and exports by 121,000 bbl/d in April, and to follow it up with more cuts in the following months. Contrary to these pledges, the volume of its foreign sales in April dropped only slightly.

Chart 3. Russia’s exports of crude oil including gas condensate to non-CIS countries between December 2023 and April 2024

Source: Argus Eurasia Energy.

However, Russia’s foreign sales of petroleum products decreased more markedly. According to data cited by the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies,[4] Russia’s total fuel exports by sea fell by almost 10% in March compared to February, dropping to 2.5 million bbl/d. This fall partly stemmed from the government’s decision to halt gasoline exports. However, there were also declines in exports of other products, whose sales abroad are much more important to the Russian industry, such as diesel and fuel oil. The negative trend also continued in April: according to the IEA, Russian exports of petroleum products fell by 15% m/m. Sales of diesel, one of the most important fuels in the structure of Russian exports, dropped to 762,000 bbl/d. Since the start of the year, they have fallen by nearly 400,000 bbl/d, or 34%.[5]

Ukrainian attacks have no impact on oil prices

On the global level, the success of the Ukrainian strikes has sparked fears in Western public opinion that the market could be destabilised, resulting in significant price increases. As the Financial Times reported, this is why the US administration has been critical of the Ukrainian strikes.[6] Its lack of support for the attacks on Russian fuel infrastructure has been explained by the fact that there is a direct link between the global price of oil and fuel prices in the US. Rising crude prices have a negative impact on US public sentiment, which is particularly important in an election year.

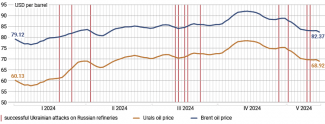

However, we can hardly connect the Ukrainian attacks to the increase in oil prices that was seen during the first quarter of this year, when Ukraine carried out successful strikes on refining facilities in Russia; one exception was the first attack on Novatek’s terminal in Ust-Luga in January, which triggered what can be interpreted as a market reaction to the emergence of a new supply-side factor. Over the first three months of 2024, crude did rise from around $60 to $72 per barrel (Russia’s Urals brand), but this price trend was driven primarily by geopolitical tensions in the Middle East,[7] revised forecasts for global oil demand and further production cuts by the OPEC+ cartel. Indeed throughout March, the month when Ukraine carried out the biggest number of successful attacks on refineries in Russia, the price of the Urals brand rose by just two dollars while that of Brent inched up by one and a half dollars. This suggests that there has been no direct correlation between the Ukrainian strikes and the global market. For comparison, after Israel attacked the Iranian consulate in Damascus on 1 April, the price of crude soared by more than five dollars within a week.

Chart 4. Changes in oil price from 1 January to 15 May 2024 against the background of Ukrainian attacks on Russian refineries

Source: Neste.

At the same time, it is possible that Ukraine has heeded the messages coming from the US; hence there has been a certain shift in how it picks targets for attacks. In January, Ukrainian drones successfully struck two facilities that produce fuel for export, and appear to have attempted to strike the oil port in Ust-Luga.[8] Since February, however, Ukrainian drones have mainly targeted Russian facilities that primarily supply the domestic market. The exceptions include an unsuccessful strike on the facility in Kirishi, which exports a large part of its production, and attacks on 17 May on several targets including the port of Novorossiysk (an oil terminal is located nearby).[9]

By focusing on refineries that are important for the Russian market, Ukraine has caused a number of problems inside Russia itself. Interestingly, reduced refining capacity in Russia has translated into higher supplies of crude; this is because the sector has been forced to export larger volumes of this raw material, which has had a moderating effect on prices. In addition, the need to sell excess quantities of crude, which goes to ports rather than refineries, has forced Russian exporters to urgently look for customers, possibly by offering more generous discounts.

At the same time, we should bear in mind that irrespective of the actions Ukraine takes, Russia has been deliberately driving prices up, as illustrated by its confusing communication within the OPEC+ cartel. Moreover, in 2023 Russia temporarily halted gasoline and diesel exports as a result of its own regulatory and fiscal missteps[10] which, contrary to many predictions, did not trigger a spike in global fuel prices.

Necessary government intervention

The drop in fuel production caused by the Ukrainian attacks has forced the Russian government to take numerous measures aimed at preventing prices from rising above the average inflation rate in the country. It should be noted that thanks to the government’s intervention and the industry’s flexible attitude, Russia has effectively managed to avoid shortages on the market during the period of the most serious shutdowns of its refining capacity as a result of the Ukrainian strikes.

The Russian government’s first countermeasure was to impose a ban on gasoline exports.[11] It decided to do so on 27 February, even before the Ukrainian drone attacks escalated. Alongside this decision, it also raised the requirement for producers to sell diesel on the domestic exchange from the previous 12.5% to 16% of their total production volume.

However, these regulatory changes failed to halt the trend of rising wholesale fuel prices, which reflected fears of local shortages as a result of uneven market supply.[12] On 22 March, 2 April and 25 April, deputy prime minister Alexandr Novak hosted government meetings which were attended by officials from the country’s oil & fuel companies and Russian Railways. According to press releases, they discussed the issue of prioritising fuel supplies for the domestic market.[13] Unofficial media reports said that the government had instructed its subordinate institutions to give priority to fuel supplies over other categories of goods,[14] and also told them to increase the financial penalties for delays in unloading railway wagons with petroleum products.[15]

In the end, the government managed to avoid shortages precisely because it prioritised redirecting production from intact refineries and reducing fuel exports, which allowed it to saturate the domestic market. The industry also tapped into the reserves it had already accumulated.[16] Supplies from abroad were important as well. According to Reuters, Russia increased its imports of gasoline from Belarus several-fold;[17] this report was later confirmed by decision-makers.[18] Furthermore, there were unconfirmed reports that Russia had asked Kazakhstan to set up a fuel reserve which could be released in the event of shortages in the Russian Federation.[19]

Continued Ukrainian attacks could destabilise the Russian market

The scale of the Russian government’s intervention to date indicates that Ukraine has managed to cause considerable trouble for both the Russian oil & fuel sector and the Kremlin’s decision-makers. These attacks have forced the industry to incur further costs in order to repair the refineries; meanwhile, production has resumed amidst the Western sanctions that have prevented Western companies from servicing these installations and made it impossible for Russia to import components from the West.[20] Russian companies are also devoting significant resources to bolstering their defences against drone attacks. According to reports in independent Russian media, this process is ongoing and costly,[21] particularly as the decision-makers have sent a clear message that companies should not count on the state to provide extensive assistance in this regard.[22]

The decision to reduce fuel exports, a step which is necessary to maintain adequate saturation of the domestic market when refining capacity is limited, has affected an important source of revenue for this sector. Indeed, government supervision over domestic prices has made it unprofitable to sell fuel inside Russia; hence the mechanism of state subsidies as incentives for the refineries.[23] Nonetheless, the decision to force this sector to supply the domestic market at the expense of exports has increased the rift between the industry and the Russian government. In this situation, the state has to raise subsidies in order to avoid price increases and signs of discontent from companies.

Under the sanctions regime against the Russian oil & fuel sector, the government’s oversight of prices and its incentive mechanism have also reduced the flexibility with which the companies and authorities can respond to shutdowns of refining capacity, whether due to technical failures or the impact of external factors. The Ukrainian attacks have highlighted this weakness. If the scale of these attacks increases, the Russian government may have to incur further costs (for example, due to the need to provide greater subsidies to the industry) or deepen its prescriptive regulatory interventions.

Drone strikes that result in shutdowns of high-capacity refineries by halting the initial refining processes (by damaging atmospheric distillation units) or cripple facilities that produce rare types of fuel (such as high-octane gasoline) could prove particularly painful. Given the potential significance and the relatively low cost of carrying out such attacks, Ukraine is likely to press on with them and cause problems mainly inside Russia. At the same time, we should not ignore the war logic behind these strikes. Shutdowns at individual refineries create logistical tensions, which leads to uneven supplies to fuel depots and regional markets. In addition to the economic and political consequences, this is also relevant from the perspective of Russia’s ability to conduct its military operations against Ukraine.

Map. Attacks on Russian refineries between 1 January and 15 May 2024

Source: the author’s own compilation based on media reports.

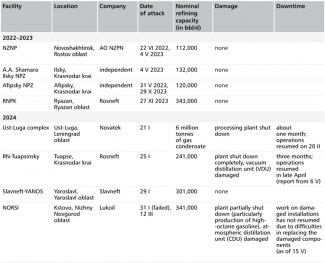

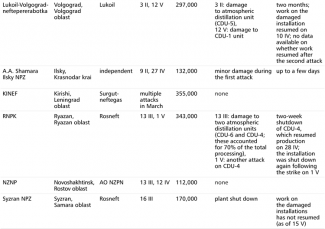

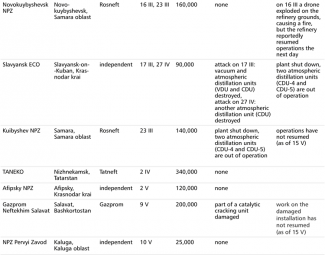

Appendix. Ukrainian attacks on refineries in Russia since the start of its full-scale invasion of Ukraine on 24 February 2022 to 15 May 2024

[1] Estimates from the International Energy Agency (IEA) and Reuters.

[2] The IEA has estimated that in March 2024, Russian oil production (excluding gas condensate) increased by 10,000 bbl/d m/m to 9.41 bbl/d. By contrast, Bloomberg’s estimates have suggested that production rose by around 90,000 bbl/d in this period.

[3] ‘Новак анонсировал новое добровольное сокращение добычи нефти в России’, РБК, 3 March 2024, rbc.ru. The pledge to cut sales was made based on the average exports in May-July 2023, which stood at around 4.8 million bbl/d.

[4] A. Economou, B. Farren-Price, Russian Oil Refining: in the Crosshairs, The Oxford Institute for Energy Studies, April 2024, oxfordenergy.org.

[5] ‘Экспорт мазута и нафты из России в апреле упал до антирекорда’, РБК, 6 May 2024, rbc.ru.

[6] B. Hall et al, ‘US urged Ukraine to halt strikes on Russian oil refineries’, Financial Times, 22 March 2024, ft.com.

[7] Including the Houthi movement’s obstruction of transit on the Red Sea and the Iranian-Israeli escalation.

[8] These successful attacks hit the refinery in Tuapse and Novatek’s terminal in Ust-Luga. Meanwhile, a downed unmanned aircraft was found near the oil port.

[9] If this does not prove to be an isolated case of a strike on export infrastructure, the bombing of the oil port near Novorossiysk may suggest that Ukraine has broadened its catalogue of targets in response to the messages coming from the US. During a visit to the Ukrainian capital on 15 May, US Secretary of State Antony Blinken reiterated that Washington does not support attacks on targets inside Russia using US weapons. However, he said that it was up to the Ukrainians to make the final decision on how to wage this war.

[10] For more see F. Rudnik, ‘Fanning the flames: crisis on the Russian fuel market’, OSW Commentary, no. 548, 18 October 2023, osw.waw.pl.

[11] ‘Правительство РФ запретило экспорт бензина с 1 марта по 31 августа’, Интерфакс, 29 February 2024, interfax.ru. A failure at the refinery in Nizhny Novgorod in January caused a significant drop in production of high-octane gasoline; these exports were supposed to help avoid shortages of this category of fuel.

[12] Д. Козлов, ‘Бензин эмбарго не боится’, Коммерсантъ, 11 March 2024, kommersant.ru.

[13] ‘Новак поручил НК отдавать приоритет поставкам топлива на внутренний рынок’, Интерфакс, 2 April 2024, interfax.ru.

[14] Д. Козлов, Н. Скорлыгина, ‘Топливу еще повезет’, Коммерсантъ, 21 March 2024, kommersant.ru.

[15] Д. Козлов, ‘От простоя к сложному’, Коммерсантъ, 1 April 2024, kommersant.ru.

[16] Idem, ‘Бензин выехал на запасах’, Коммерсантъ, 4 April 2024, kommersant.ru.

[17] According to a report by Reuters, in the first half of March, Belarus supplied 3000 tonnes compared to 590 tonnes in February; in January, Russia did not import any fuel from this country at all. ‘Exclusive: Russia increases gasoline imports from Belarus as domestic supplies shrink’, Reuters, 27 March 2024, reuters.com.

[18] 'РФ договорилась с Белоруссией о росте импорта топлива, если будет необходимо’, Парламентское Собрание Союза Беларуси и Росии, 28 March 2024, belrus.ru.

[19] ‘Exclusive: Russia seeks gasoline from Kazakhstan in case of shortages, sources say’, Reuters, 8 April 2024, reuters.com.

[20] R. Harvey, ‘Exclusive: US sanctions hamper Russian efforts to repair refineries’, Reuters, 4 April 2024, reuters.com.

[21] M. Жолобова, ‘Российские компании строят свою систему ПВО’, Важные Истории, 21 March 2024, storage.googleapis.com.

[22] К. Антонов, ‘Глава Татарстана призвал предприятия самим защищаться от дронов’, Коммерсантъ, 3 April 2024, kommersant.ru.

[23] This is the so-called price-damping mechanism. This involves the payment of subsidies to fuel operators in situations where the export price of fuel is higher than the domestic price. In this way, the state encourages the industry to actively sell its products in Russia, thus driving down wholesale prices and avoiding shortages. Government subsidies compensate the sector for some of the losses resulting from the fact that it has to sell its production on the domestic market at reduced, government-supervised prices.