Elections to the European Parliament: the beginning of an electoral marathon in Germany

For German politicians, the European Parliament (EP) election is the most important test of voting intentions ahead of the regional elections in eastern federal states planned for this autumn and the elections to the Bundestag in 2025. This is why domestic issues, in particular the proposal to curb migration and the commitment to ensure security, are important elements of the platforms which the parties prepared for the recent EP election campaign. The importance of this campaign and the outcome of the election is corroborated by the strong involvement of Chancellor Olaf Scholz and the majority of ministers in it. However, the opposition Christian Democrats (CDU/CSU) are topping the polls with their new conservative platform.

The reduction in the voting age means that 16-year-olds were allowed to vote in the EP elections for the first time in history. Until recently, young people supported the Greens and the Liberals (FDP); at present, however, they are increasingly favouring the Alternative for Germany (AfD). This far-right, anti-EU and anti-immigrant party views the EP elections as an opportunity to strengthen its position in the EP and German politics. However, numerous scandals which occurred towards the end of the campaign may have undermined the party’s prospects for success. The high level of support for the Christian Democrats in German politics and for the European People’s Party (EPP) in the EP increases Ursula von der Leyen’s chances of being elected as president of the European Commission (EC) for a second term. Despite this, the German government’s uncertain support continues to be a problem for her, as the German leadership makes its backing conditional upon von der Leyen’s withdrawal from cooperation with the European Conservatives and Reformists group (ECR) in the EP.

In Germany, a total of 65 mn individuals were entitled to vote in the EP election on 9 June, of which 61 mn hold German citizenship. According to estimates, around 9 mn citizens in the latter group have a migrant background and make up 17% of the electorate.[1] This is the first election in which 16-year-olds were allowed to vote, which increased the number of potential voters by around 1.3 mn. In this age group, the proportion of individuals with a migrant background is particularly high, around 45%.

Out of all the EU member states, Germany has the largest group of potential voters. As a consequence, the German election results have a significant influence on the balance of power in the EP. As in 2019, Germany will elect 96 MEPs. The total number of candidates is 1413, 486 of whom are women (34%).

Unlike in the elections to the Bundestag and the Landtags, no electoral threshold has been defined in the EP election, which encourages smaller parties and initiatives to take part.

A campaign overshadowed by attacks

The campaign ahead of the EP election coincided with the preparations for the September elections to the Landtags of Saxony, Thuringia and Brandenburg, and for local elections in some federal states. This has made meetings and rallies even more intense, and has also led to acts of aggression targeting politicians on an unprecedented scale. Although attacks on party activists are nothing new in Germany, their current intensity and brutality have clearly been on the rise. Politicians of the Greens and the AfD are the most frequent victims of these attacks.[2] The individuals targeted include both average activists and prominent politicians such as Vice-Chancellor Robert Habeck and Vice-President of the Bundestag Katrin Göring-Eckardt (both from the Greens), and deputy head of the Bundestag’s Parliamentary Oversight Panel Roderich Kiesewetter (CDU).[3] In response to the attacks, federal interior minister Nancy Faeser (SPD) demanded that legal sanctions for crimes targeting politicians and party activists should be toughened.

Disinformation activities intended to disrupt the election, especially by Russia and China, are another threat. Faeser repeatedly argued that Germany was subject to espionage, sabotage, disinformation and propaganda activities which the perpetrators have been using “to divide us as a society and weaken us politically and economically”.[4] The interior ministry has enhanced its internal structures to combat disinformation at an early stage. In addition, the government plans to hire analysts and increase the application of artificial intelligence to be able to identify and neutralise disinformation campaigns on social media more promptly.

The unpopular ‘chancellor of peace’

For all the parties the EP elections were the most important test ahead of the elections to the Bundestag planned for autumn 2025, and also offered an opportunity to improve their campaign strategies and identify which issues are of key importance to the voters. Opinion polls indicate that according to the German public the currently most important problems faced by the EU include migration policy (41%), international conflicts (34%), climate change & environmental protection (21%) and the economy (20%).[5] In a poll conducted a month before the elections, the respondents indicated the same issues as the most important problems in German domestic politics.[6]

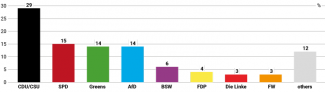

Chart 1. Level of support for individual political parties ahead of the EP elections (May 2024)

Source: author’s own analysis based on a survey conducted by Infratest dimap.

In an attempt to respond to the concerns voiced by German voters, the Social Democrats (SPD) promoted Scholz as the ‘chancellor of peace’ who is able to guarantee security in times of crisis. They saw this as an opportunity to improve their low approval ratings (see Chart 1). In the opinion of the majority of SPD supporters, the party leader’s hesitation as regards providing military aid to Ukraine is a wise move, and agree with his arguments that this could provoke an escalation of the war.[7] Promoting Scholz as the leader of the electoral race is mainly intended to mobilise the Social Democrats’ electorate. He is not popular with other social groups (around 76% of the respondents argue that he is not performing his duties in an adequate manner).[8] If the electoral result is significantly below expectations (around 15%), the party’s internal criticism of the chancellor will probably increase.

The Greens and the FDP (the other parties in the governing coalition) strongly support the proposal to increase aid (including military aid) for Ukraine, and their campaign materials clearly emphasise such issues as freedom, security and democracy. The result of the EP elections will be of key importance especially to the FDP, whose level of support has been insignificant for several months and usually falls below 5%. In the event of their electoral failure, the Liberals will come under increasing pressure to implement their platform in government, which will cause further disputes within the coalition. Unlike in the previous EP election campaign, the voters do not attach major importance to issues linked with climate policy. This poses a challenge to the Greens, as the majority of the electorate does not view them as particularly competent with regard to hard security issues, especially curbing migration. This is why this party has focused on fighting the AfD and emphasising the importance of democracy and respect for the EU.

The opposition is on its way to victory

The CDU has been leading the polls consistently since May 2022. A positive result for the Christian Democrats will consolidate the party around its leader Friedrich Merz and will effectively secure his nomination as the party’s candidate for chancellor in 2025.[9] In addition, it will strengthen the party ahead of the elections in eastern federal states, where it will compete with the AfD. If Ursula von der Leyen retains her post as EC president, that would be the greatest EP election success for the CDU/CSU.

The elections to the EP, coming less than a year before the elections to the Bundestag, was intended to be the beginning of a string of successes for the AfD.[10] However, the popularity of Germany’s second strongest political party declined at the beginning of this year. This drop was mainly due to the emergence of a new protest party in Germany, the Sahra Wagenknecht Alliance (BSW), for which these elections were the first test of actual voter support.[11] The AfD’s slump continued when reports emerged regarding a secret meeting, attended by AfD politicians, which was focused on ‘re-emigration’, specifically a plan to expel several million individuals with migrant backgrounds from Germany.[12] Other supporters departed after scandals involving the party’s main candidates in the EP elections. Maximilian Krah resigned from his post as one of the party’s leaders and was banned from making public appearances for relativising the crimes perpetrated by the SS.[13] As a consequence of Krah’s actions, German MEPs representing the AfD were excluded from the Identity and Democracy (ID) group in the EP. This will weaken the AfD’s European influence following the elections, especially as Marine Le Pen, the leader of the French National Rally party and the key figure in the ID, has ceased to cooperate with the AfD.

Support for the anti-immigrant AfD could well increase in the aftermath of a knife attack in Mannheim at the end of May, when an Afghan man who had been legally resident in Germany since 2014 wounded several individuals with a knife, including a policeman who eventually died. The attack provoked outrage and amplified the debate on toughening migration policy and assuming a more restrictive approach to Islamists residing in Germany.

Scenarios for the future of the EU according to individual parties

The main element differentiating the platforms of individual German parties in the EP election campaign involves their approach to the EU and the directions for its development. The ruling coalition parties propose to thoroughly reform the EU’s structures and to enhance integration in areas which are of key importance to the EU’s operation. Their proposals include boosting the role of the EP, expanding qualified majority voting (QMV) in the Council of the European Union to all EU policies, and reducing the number of EU commissioners. However the key proposal involves a reform of EU treaties, which would require a special Convention to be established. For the Greens and the FDP, who favour the most far-reaching institutional reforms, this would be an opportunity to draw up an EU constitution, which is an indispensable element in the process of the bloc’s federalisation.

The Christian Democrats support a different vision, one which is closer to the present status quo. They argue that the EU’s competence should only be expanded in those areas in which its activities are more effective than those carried out by the member states, that is in the migration & asylum and security policies; the remaining areas of responsibility should remain in the member states’ scope of competence. Just like the ruling parties, the CDU/CSU supports the plan to streamline the EU’s operations, for example by reducing the number of EC officials. However the Christian Democrats would like the QMV to be expanded to the common foreign and security policy (CFSP) only.

The platforms of the AfD and the BSW form an alternative to the pro-EU proposals endorsed by other parties. Both of these parties have criticised the initiatives intended to enhance the EU’s integration and bring about its federalisation; they have accused the EU of being undemocratic and of intending to impose its will on the member states. The BSW supports the EU’s continued existence provided that the scope of competence of its institutions is reduced. The AfD’s proposals are much more radical. The party has proposed dissolving the EU and establishing a ‘Union of European Nations’ in its place, in which the member states would retain a greater degree of independence and the ability to decide freely about key aspects of their policies. In this bloc, cooperation would be based on international agreements. Its main areas would include the single market, either maintaining the common currency or establishing a new one in those states which are similar to each other in terms of their economic structure, and protection of the EU’s borders.

Stopping illegal migration

The idea that migration policy is the most important challenge, on both the national and the European levels, results from the conviction shared by a predominant portion of the German public regarding the government’s inability to deal with the growing number of foreigners arriving in Germany. The SPD, the Greens, the FDP, the CDU/CSU and the BSW[14] all share the following goals: to fight illegal immigration and its causes, to protect the EU’s internal borders, to launch actions to attract a qualified workforce, and to reform the EU’s migration pact. However, these parties have different visions on how to achieve these goals. While the Greens and the SPD propose expanding the common asylum policy and are opposed to the plan to relocate the asylum procedure to third countries, the FDP’s approach is similar to the one shared by the opposition Christian Democrats and the BSW, as all these three parties support a solution in which applications for asylum in the EU should be submitted and considered in safe third countries. They also have highlighted the need to enhance the protection of the EU’s external borders. The AfD has adopted the most radical approach.[15] For example, in order to curb the number of migrants arriving in Europe as much as possible, aside from the solutions proposed by the remaining parties, it intends to limit the number of individuals seeking protection whom specific states accept, and to make this protection provisional.

NATO as guarantor of security

In this year’s campaign, unlike the 2019 one, security issues are of huge importance to the voters, mainly thanks to Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine. The ruling parties and the opposition Christian Democrats jointly support the plan to enhance the common security & defence policy (CSDP) as a complementary element to NATO, rather than as an alternative to it. The parties also agree that it is necessary to expand the European defence industry, increase investment in this sector and harmonise the rules regarding the export of European-made armaments. All these proposals are in line with the platforms of pro-EU European political parties.[16]

In the field of security, their platforms differ as regards Germany’s relationship with Moscow: although the ruling parties and the opposition Christian Democrats have condemned Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and its imperialist policy, it is the Greens and the FDP that openly support the proposal to maintain the Kremlin’s international isolation and to expand the economic sanctions. A similar division is evident regarding China: the CDU/CSU and the Social Democrats have tersely described the EU’s relations with Beijing as a form of partnership, competition and systemic rivalry, whereas the Greens and the FDP argue that at present these relations are limited to the latter two categories, and that the EU should step up its activities to reduce its economic dependence on China.

The extreme parties have a totally different vision of European security. The AfD and the BSW have proposed to make Germany independent of NATO and the US. They have called for the war in Ukraine to be ended as soon as possible (which would effectively mean forcing Kyiv to capitulate, including by halting military support), to conclude an agreement with Russia and to base European security architecture on the Organisation for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE); this would involve a return to regular cooperation with the Kremlin, effectively equating to recognising a sphere of influence for Russia. These parties have an equally submissive attitude to China, which in their view is too important to Germany to curb bilateral relations in any way.

The AfD and the BSW have different approaches to the production of arms. The BSW views it as one of the main sources of threats to Europe, and proposes placing an emphasis on diplomacy which it considers the most effective tool to guarantee peace and stability. The AfD for its part has proposed expanding the Bundeswehr’s arms and personnel potential, concluding bilateral cooperation agreements between states, enhancing Europe’s defence industry and prioritising European arms producers in procurement initiatives. The party has mainly adopted this proposal with German economic interests in mind.

Despite the Russian invasion and the signing of an association agreement between the EU and Ukraine, enlargement policy is not among the key issues discussed in the German political parties’ electoral platforms. The prospective EU membership of Ukraine, Moldova, Georgia and the Western Balkan states is supported by the pro-European parties, which have formulated two conditions to be met prior to EU enlargement. These involve the reform of the EU’s institutions and the fulfilment of all the required accession criteria by the candidate countries, with special emphasis on respect for democratic standards, the rule of law and European values. Due to the prolonged duration of the accession process, they have proposed a model of gradual integration which the present EC prefers.[17] The AfD and the BSW are against any EU enlargement.

The modified version of the European Green Deal

The European Green Deal is the subject of general consensus among the pro-European parties. The Deal’s main goal is to make Europe carbon neutral by 2050, including by increasing the share of renewable energy sources in the EU’s energy mix and boosting investment in clean technologies. In this context, the differences in specific party platforms involve the controversial Fit for 55 package, which is a set of regulations intended to result in the implementation of the Green Deal. As the most vocal advocates of climate protection, the Greens support the introduction of the package, although they have proposed the establishment of a climate social fund in order to ease the financial consequences for private households. This fund could be fed by the proceeds from emissions trading, and would involve payouts of financial support to citizens of EU member states.

The SPD and the CDU/CSU have adopted a slightly more nuanced stance, and signalled that although the goals of the European Green Deal seem appropriate, the system should be adapted to the needs and possibilities of the EU’s citizens. The Social Democrats have emphasised that the process of adapting national laws to EU requirements should involve measures to guarantee sufficient social security to all citizens. The Christian Democrats would like to make the pace of development of the European Green Deal conditional upon the economic situation in individual countries, and to ensure that the EU retains its competitive advantage over other global economies. The FDP has assumed the most critical approach to the Green Deal; they propose halting the implementation of the new regulations linked with it and revoking the ban on the sale of new cars with internal combustion engines which will come into force from 2035.

The AfD strongly rejects the EU’s energy policy. In its view, this should be shaped by individual nation states which should be allowed to continue to generate ‘cheap’ energy from fossil fuels and nuclear sources. The BSW has also highlighted the importance of ‘traditional’ energy sources. As an element of potentially resetting the EU’s relations with Moscow, it has proposed the resumption of oil and gas imports from Russia. Both parties have criticised the plan for an EU-wide phase-out of internal combustion cars.

The EU economy: high on competitiveness, low on bureaucracy

As regards the EU economy, the proposals endorsed by Germany’s pro-European parties seem to reflect the EC’s calls for strengthening the single market and the EU’s global position as a promoter of development of new technologies which is resilient to threats, has a diversified network for importing key raw materials, and is capable of competing with countries such as China and the US. However, the pro-European parties differ in how they place emphasis regarding these issues. The Christian Democrats and the Liberals have emphasised the reduction of EU bureaucracy, reject the communitisation of debt, and support the SME sector and start-ups. The Greens for their part have highlighted the link between the development of the EU economy and investment in new technologies and clean energy such as electric cars. The SPD argues that harmonising the economic development with social welfare is of fundamental importance. Although the BSW has backed some of these proposals, such as support for SMEs and the promotion of a climate-friendly economy, it is mainly focused on regional and cross-border cooperation. The AfD’s stance is radically different; they believe that numerous policies should be returned to the hands of the nation states, and the EU replaced with a European economic community of sovereign states.

Summary

For Germany’s political parties, the EP elections have mainly been of importance in the context of domestic politics. The lessons learnt from the campaign will enable them to correct their mistakes and adapt their messaging to the voters’ preferences ahead of the upcoming German elections. While the Christian Democrats are the favourites in the polls, the remaining parties cannot be sure of their results. If these are not satisfactory, the parties may be encouraged to modify their electoral strategies and intensify their debates about the status of their leaders. In this context, Chancellor Scholz and the FDP leader Christian Lindner in particular may find their levels of support are called into question, and there may be increasing attempts to challenge their positions within the party structures. If the ruling parties’ results are poor, there will be increased pressure from the individual coalition members to push through their own platform proposals. This will make it difficult for the coalition to cooperate smoothly, although the break-up of the coalition seems unlikely.

The recent campaign has once again shown that although the AfD enjoys a very high approval rating, the biggest threat to it comes from its own activists. It should be expected that ahead of the elections in the eastern states and the federal elections, the party will seek to consolidate around its leaders. The party’s congress, which will be held in Essen at the end of June and will elect a new leadership, will be a major test for the AfD.

The likely success for the EPP will increase von der Leyen’s chance of getting elected for her second term as EC president. However, Berlin may prevent this. According to the coalition agreement, the Greens will have the right to nominate a German member of the EC, provided that the EC’s president is not a German national. The SPD and the Greens, who have positioned themselves as the counterbalance to the far-right parties, see von der Leyen’s attempt to win support from the ECR as a red line. The FDP has focused its campaign on criticising the current head of the EC, among other topics. However, it cannot be ruled out that the stance adopted by the ruling parties is based on a calculation which will enable them to win over voters and persuade the new EC to make concessions. Regardless of this, Germany will ultimately support von der Leyen’s candidacy during the vote in the European Council.

The AfD’s political affiliation in the EP remains unclear. After the party’s exclusion from ID, the ECR is likely the only group which could in theory consider adopting these German MEPs. However, due to several statements by AfD members in which they relativised history and openly expressed pro-Russian views, this scenario is unlikely. The AfD’s MEPs will be unable to form their own group in the EP (because to do so requires 23 MEPs representing at least a quarter of the member states). Therefore, they will most likely continue to act as non-attached MEPs and will support ID and ECR proposals during voting.

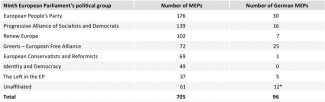

Table. German MEPs in the ninth European Parliament’s political groups (2019–24)

* Ten of Germany’s twelve unaffiliated MEPs are AfD members, who were excluded from the Identity and Democracy Group in May 2024.

Source: authors’ own analysis based on data published by the EP, as of 28 May 2024.

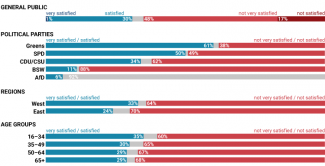

Chart 2. The German public’s support for EU policies (May 2024)

Source: authors’ own analysis based on a survey conducted by Infratest dimap.

[1] In 2021, Germany’s population included around 8 mn adults with a migrant background. In the federal elections in 2021 they accounted for around 14% of all voters, compared to 10.2% in 2017. Before the 2013 federal elections the proportion was around 10%. See ‘Wie viele Wahlberechtigte haben einen Migrationshintergrund?’, Mediendienst Integration, May 2024, mediendienst-integration.de.

[2] In 2022, AfD politicians fell victim to 782 criminal acts across Germany, while Green politicians suffered 296 criminal acts. According to preliminary statistics, 2023 saw 478 criminal acts against the AfD and 1219 against the Greens. In 2023, acts of violence were most frequently perpetrated against AfD politicians (86, compared to 62 for the Greens and 35 for the SPD), whereas in 2022 51 such acts were recorded for the Greens and 40 for the AfD and the SPD each. See ‘Angriffe auf Politiker, Parteibüros und Wahlplakate bis einschließlich 2023’, Deutscher Bundestag, Drucksache 20/10177, 26 January 2024, dserver.bundestag.de; ‘Innenminister Armin Schuster verurteilt Angriffe auf Wahlhelfer scharf - Task Force des LKA ermittelt’, Sächsisches Staatsministerium des Innern, 4 May 2024, medienservice.sachsen.de.

[3] A survey conducted by the University of Duisburg-Essen in 2022 showed that around 60% of local-level politicians had experienced hostility and attacks. Slightly under half of the respondents reported that they had received threatening or harassing phone calls, e-mails, letters etc. Half of them experienced hostility in social media or during in-person meetings. The majority of incidents happened in Dresden, Erfurt and Munich. See ‘Anfeindungen und Aggressionen in der Kommunalpolitik / Politisch Engagierte auf allen Ebenen betroffen’, Heinrich Böll Stiftung, 7 December 2022, boell.de.

[4] ‘Rede der Bundesministerin des Innern und für Heimat, Nancy Faeser’, Die Bundesregierung, 25 April 2024, bundesregierung.de.

[5] ‘ARD-DeutschlandTREND Mai 2024’, Infratest dimap, infratest-dimap.de.

[6] ‘ARD-DeutschlandTREND April 2024’, Infratest dimap, infratest-dimap.de.

[7] K. Frymark, L. Gibadło, ‘The party of peace: the SPD is sending signals about the freezing of the war in Ukraine’, OSW, 19 March 2024, osw.waw.pl.

[8] ‘ARD-DeutschlandTREND Mai 2024’, op. cit.

[9] K. Frymark, ‘A return to conservatism: the CDU’s new platform’, OSW, 8 May 2024, osw.waw.pl.

[10] Idem, ‘A general rehearsal: strategies to contain the AfD’, OSW Commentary, no. 598, 27 May 2024, osw.waw.pl.

[11] Idem, ‘Germany: the launch of the pro-Russian Wagenknecht party’, OSW, 29 January 2024, osw.waw.pl.

[12] Idem, ‘Germany: mass demonstrations against the AfD’, OSW, 23 January 2024, osw.waw.pl.

[13] He said, “Not every action carried out by the SS can unequivocally be viewed as a crime.”. In his earlier statements Krah has also repeatedly relativised Germany’s responsibility for WW2 crimes. See S. Gaschke, ‘«Unsere Vorfahren waren keine Verbrecher»: Der AfD-Spitzenkandidat Krah will die Christlichdemokraten «zerstören» – auch mithilfe türkischstämmiger Wähler’, Neue Zürcher Zeitung, 7 September 2023, nzz.ch.

[14] The SPD’s political platform: ‘Gemeinsam für ein starkes Europa. Das Wahlprogramm der SPD für die Europawahl 2024’, spd.de.The Greens’ political platform: ‘Was uns schützt. Europawahlprogramm 2024’, cms.gruene.de.The FDP’s political platform: ‘Entfesseln wir Europas Energie für mehr Freiheit und mehr Wohlstand. Das Programm der FDP zur Europawahl 2024 Europa’, fdp.de.; The CDU/CSU’s political platform: ‘Mit Sicherheit Europa. Für ein Europa, das schützt und nützt. Wahlprogramm von CDU und CSU zur Europawahl 2024’, cdu.de.; The BSW’s political platform: ‘Programm für die Europawahl 2024’, bsw-vg.de.

[15] The AfD’s political platform: ‘Europa neu denken! Programm der Alternative für Deutschland für die Wahl zum 10. Europäischen Parlament’, afd.de.

[16] See Ł. Maślanka, ‘Między maksymalizmem a odrzuceniem. Europejskie partie polityczne i grupy parlamentarne wobec unijnej polityki bezpieczeństwa’, Komentarze OSW, no. 599, 28 May 2024, osw.waw.pl.

[17] M. Szpala, L. Gibadło, ‘The European Commission outlines its concepts for the EU’s enlargement and internal reforms’, OSW, 29 March 2024, osw.waw.pl.