Short-term stability and long-term problems. The demographic situation in Russia

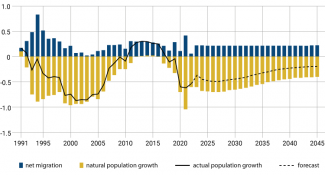

Russia has seen a negative natural population growth rate for three decades, except for a brief period between 2013 and 2015. Since 2020, the natural population decline has no longer been offset by a positive migration balance. As a result, the Russian population has been consistently decreasing, primarily due to long-term demographic problems such as a decline in the birth rate and an increase in mortality. These adverse trends have been compounded by immediate challenges: the COVID-19 pandemic, which caused a noticeable increase in the number of deaths, and the ongoing war with Ukraine, the demographic impact of which is difficult to estimate, since the number of casualties has not been disclosed by the authorities.

On the one hand, the Kremlin declares a desire to improve demographic indicators and implements targeted solutions to improve the birth rate. On the other hand, it makes ad hoc, inconsistent moves that adversely affect the influx of immigrants needed by Russia. Moscow’s priorities have shifted from domestic social issues to the armed conflict. Consequently, efforts to encourage population growth through natural methods and to attract immigrants to fill the population gap are now much lower on the agenda.

Demographic trends suggest that in the long term, Russia will face depopulation and, as a consequence, major economic problems, the most serious being the growth of socio-economic disparities between regions, the collapse of the labour market, and even a decline in defence capabilities. In the short term, however, Russia can sustain regular conscription and mobilisation of reservists to fight in the war without dramatic domestic consequences. This causes increasing labour shortages, which are already evident in critical sectors such as the defence industry. As a result, prices for goods and services are rising, and the situation is further exacerbated by restrictions on hiring immigrants.

Methodological problems

The statistical data underpinning the analysis of the demographic situation in Russia originate from official sources, primarily Rosstat publications: the Demographic Yearbook of Russia 2023,[1] the Socio-Economic Situation of Russia (covering the first quarter of 2024),[2] and the 2020 Census.[3] Given the neo-totalitarian nature of the Kremlin regime, relying on such sources entails numerous problems and risks. Some data, especially those concerning war casualties, have been classified and not included in the statistics. During the ongoing conventional war with Ukraine and hybrid war with the West, the Russian government is unwilling to disclose information that could harm its image or reveal its weaknesses.

Some key data on population numbers are adjusted. This is practiced primarily at the regional level, where information is collected and forwarded to federal institutions. The value of the regional subsidies granted by the federal authorities depends on the reported population figures. The most peripheral regions, which are highly dependent on central funding, are the most notorious for this practice. These include the republics of the North Caucasus, particularly Ingushetia and Dagestan, as well as Krasnodar Krai.[4]

Another problem is the failure of regional authorities to publicise negative demographic trends due to fear of criticism from Moscow for poor performance. Additionally, the lack of comprehensive data from official sources makes it difficult to accurately assess the scale and dynamics of labour migration within Russia. The available data only accounts for either the number of entries into the country (which should not be equated with the number of people residing long-term) or work permits (many migrants work illegally). Aggregate immigration figures, especially for labour migration, cited by Russian government representatives and presented in the media, are inconsistent.

As a result, there is no reliable, detailed information on the extent of Russia’s worsening demographic problems in recent years, particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic and the war. The biggest doubts arise around the actual number of births and deaths, including war casualties, as well as the dynamics of labour migrant inflows. Some of the assessments in the text relating to these statistics are hypotheses. Even the official figures for such a basic indicator as the current population are questionable.

According to official data, Russia currently has a population of around 146 million. This figure includes the population of Crimea, illegally annexed by Russia in 2014, but does not cover other territories in Ukraine that are occupied by the Kremlin. Russian independent demographers suggest that this number is inflated by as much as 5–5.5 million people.[5] The inclusion of Crimea in statistics in 2015 increased the figure by an additional 2.3 million. Despite this, there has been an actual population decline since 2020. Given the aforementioned datareliability issues, the true scale of the decline may be significantly greater than what official statistics show.

Declining fertility

Long-term negative demographic trends in Russia primarily include declining fertility, an ageing society, and increasing mortality. In terms of birth rate, Russia aligns with typical values for developed countries. However, mortality rate – especially among working-age men, who are a key economic resource – are significantly higher and comparable to those in some African countries.

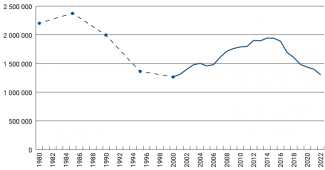

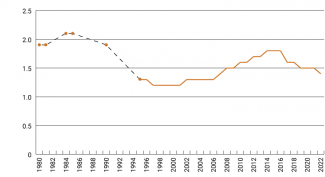

Russia has experienced negative natural population growth since the early 1990s, except for a brief period from 2013 to 2015. During this time, mainly due to state-implemented measures to stimulate fertility (notably the Maternity Capital programme), population growth was positive (24,000–32,000 annually). However, in 2016, the negative trend resumed and intensified. In recent years, the number of children born in Russia has declined; in 2021, 2022 and 2023, the numbers stood at 1.39 million, 1.30 million and 1.26 million, respectively. In 2022, the birth rate was 9 per 1,000 residents – one of the lowest in the world.[6] Moreover, in 2023, the fertility rate (the average number of children per woman of childbearing age) stood at 1.4, reaching its lowest level in 17 years.[7] This rate is comparable to those in developed European countries (in 2022, the EU average was 1.46, and in Poland, it was 1.26) and does not ensure population replacement, which requires a rate of 2.15.

According to Rosstat, the recent decline in Russia’s fertility rate has slowed, and its value has stabilised. Official forecasts predict that it will slowly grow in the coming years. Therefore, so far, there is no current indication that the war has caused or will cause a decrease in fertility in Russia.

Partly, this is the result of the Kremlin’s relatively effective pro-family policies, especially the Maternity Capital programme and other financial incentives offered by the state, including gradually increasing tax breaks and preferential mortgage loans for families with children. Family and procreation, as well as the government’s efforts to support them, are important topics in political rhetoric and propaganda. The key initiative for stimulating fertility is the Maternity Capital programme. Its introduction in 2007 coincided with a rise in fertility, as the 1980s baby boom generation reached reproductive age. In 2015, the fertility rate stood at 1.78, which was a record-high value in modern Russian history. However, since it was uncertain at the end of that year whether the programme would be continued, the birth rated declined in 2016.[8] Starting from 2020, the benefit which was originally granted for the birth of a second and subsequent child, began to be paid for the first child as well. This has partially demotivated Russian families from having additional children and has negatively impacted the number of births. Currently, the Maternity Capital programme is set to run until 2030, and since it is a key governmental incentive for procreation, it will likely be extended beyond this date.

Chart 1. Number of live births in Russia from 1990–2022

Source: Demographic Yearbook of Russia 2023.

Chart 2. Fertility rate in Russia from 1990–2022

Source: Demographic Yearbook of Russia 2023.

Paradoxically, governmental welfare funding targeted at groups involved in the conflict also helps prevent further decline in fertility. This includes especially high salaries for soldiers, various benefits in the event of injury or death at war and allowances for families, all of which have a real impact on improving the financial situation of Russian families. These measures are particularly effective in poorer regions, where residents have limited career development opportunities making them prime targets for recruitment for the war. These regions often represent areas with high fertility rates, which is typical of ethnic groups other than Russians.

The result government’s mobilisation efforts are skilful and targeted, which lead the Russian public to believe that life goes on as usual. In a way it serves as an incentive for procreation. For some families, having a third child (in addition to the guarantee of receiving the Maternity Capital benefit) has become a way to avoid conscription, as fathers of large families are exempt from mobilisation by law. Despite these measures, the prospects for a significant increase in fertility in Russia are limited. The country is undergoing a so-called second demographic transition, typical of developing nations, where fertility and birth rates decline while life expectancy increases. The prolonged war negatively impacts this as well, as studies show it affects the well-being and sense of security among the Russian public, and these factors play an important role in family planning. For example, according to an October 2023 survey by Russian Field, Russians are pessimistic: 43% expect their financial situation to worsen within the next year or two, while only 21% anticipate improvement. This pessimism is more pronounced among those under 45. Additionally, 54% of respondents feel negative or extremely negative emotions when exposed to information about the so-called military operation.[9]

In terms of fertility, Russian society is not homogeneous. The fertility rate is significantly higher in regions inhabited by non-Russian ethnic groups, especially Muslim communities. The highest rates are recorded in the republics of the North Caucasus and in Siberia, in the so-called ethnic republics. In 2023, women in the Chechen Republic had the highest fertility rate (2.66), followed by Tuva (2.44) and the Altai Republic (2.03). Conversely, the lowest fertility rates – less than one child per woman – were recorded in Leningrad Oblast and Sevastopol (0.88 and 0.98, respectively).

This birth rate dynamic leads to an increasing share of the ethnically non-Russian population in society. The government’s intensified naturalisation policy for immigrants further amplifies this effect. According to census results, the number of residents identifying as ethnic Russians fell from 111 million in 2010 to 105.6 million in 2021 (from 78% to 72% of the population). Demographers suggest that the actual decline is even greater because some participants in the latest census (over 16 million people) did not disclose their ethnic background. This may have been due to fears of persecution based on ethnicity and because census takers, partly for political reasons, intentionally omitted this field in questionnaires when the declared ethnic identification was other than Russian.[10]

Ageing society

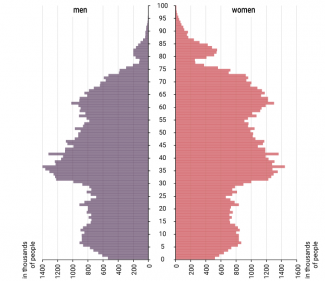

Regarding the aging of society, at the beginning of 2023, the average age of men in Russia was 38.1 years, and in the case of women, it was 43 years; these are the highest values since measurements began (compared to 34.6 years for men and 39.4 years for women in 2000). Life expectancy is also at a record high – 72.7 years in 2022 (compared to 65.3 years in 2000). However, this is significantly lower than in developed countries, such as in the EU, where life expectancy in 2023 was 81.5 years. A notable point is the significant gender gap in life expectancy of Russian men (67.6 years) and women (77.8 years). On the one hand, Russians, especially men, die earlier than their Western neighbours and thus are not a burden for the pension system. On the other hand, the proportion of people of post-retirement age in Russian society is steadily increasing, leading to negative social and economic consequences.

Chart 3. Demographic structure of the population according to the 2020 census

Source: Rosstat

Increasing mortality

Another negative phenomenon is the high mortality rate. Currently, there are 14 deaths per 1,000 individuals, so this rate one of the highest in the world. According to data, 2.44 million, 1.89 million and 1.76 million people died in 2021, 2022 and 2023, respectively. The rate in 2021 was exceptionally high due to the COVID-19 pandemic, which had a severe impact on the country, resulting in a natural population decline exceeding 1 million people. Data for 2023 indicate that the situation improved and returned to pre-pandemic levels, such as in 2018 and 2019, when 1.82 million and 1.79 million people died, respectively. There is no visible impact of the war on mortality statistics for 2022 and 2023. However, data for the first quarter of 2024 indicate that mortality is slightly higher than in the same period for the previous year (by about 30,000 people). This difference could include war-related deaths.

Mortality data are crucial for the Russian Defence Ministry and the Kremlin. Official war casualty statistics have been revealed only on several occasions and are undoubtedly understated. In September 2022, the then Defence Minister Sergey Shoigu mentioned only 5,937 Russian soldier fatalities in Ukraine – his last statement on the matter. In 2022, the Defence Ministry ceased publishing data on military and family pensions for the loss of a breadwinner, as these figures could imply the scale of losses. Meanwhile, foreign sources report significantly higher numbers, with Ukrainian data suggesting 180,000 Russian casualties. According to Western estimates, the total number of killed and wounded Russian soldiers is estimated at 315,000 (US estimates) or even 450,000 (UK Ministry of Defence).[11] Such a high number of casualties (far exceeding the losses in previous wars involving Russians in Afghanistan and Chechnya[12]) should be reflected not only in demographic data but also in public sentiments. However, this topic is taboo in propaganda and public discussions, and anyone mentioning it may be punished under a law criminalising the dissemination of allegedly false information about the Russian army.

The analysis of the leading causes of death in official Russian statistics also does not reveal the impact of the war on mortality. In 2022, the main causes of death were cardiovascular diseases (nearly 832,000), cancers (281,000), and external causes (146,000), which include alcohol poisoning, road accidents, assaults, homicide, and suicides. Interestingly, the first and third most common categories often correlate with excessive alcohol consumption, a long-standing serious social problem in Russia. The catalogue of causes of death does not include a separate category for war casualties. Deaths on the front line can easily be classified under the most common categories, which is most likely happening in official statistics.

Adverse migration trends

Negative trends affecting Russia’s population also include adverse changes in migration dynamics. In recent years, there has been a decrease in the number of migrant workers coming to Russia. At the beginning of the invasion of Ukraine, Russia faced an outflow of people on an unprecedented scale, with estimates ranging from 700,000 to 800,000 individuals leaving the country. At the same time, there was a dramatic increase in the number of Russian passports issued to foreigners (from around 269,000 in 2018 to a record 735,000 in 2021), which suggests that the Kremlin currently treats naturalisation as a method to fill demographic gaps.

In past decades, the influx of immigrants positively impacted Russia’s demographic situation, but according to statistics, since 2020, positive net migration no longer compensates for the natural population decline. Negative trends in this area were initially driven by the COVID-19 pandemic and later by the ongoing war and ad hoc measures the government has taken after the terrorist attack on Crocus City Hall,[13] in March 2024. The Kremlin claims a willingness to accept immigrants for economic reasons, as advocated by representatives of ministries in charge of economic affairs, but simultaneously pursues policies that negatively affect incoming migrants.

Chart 4. Natural population growth, actual population growth and net migration for Russia

Source: Rosstat

Before the pandemic, the number of foreign workers residing in Russia fluctuated between 4 and 4.5 million. By 2022, this number had shrunk to around 3 million. According to data for 2023, only 2.15 million immigrants,[14] were legally employed in Russia, accounting for approximately 3–4% of the labour market (out of 72 million people of working age). However, Vladimir Putin provided significantly higher figures during a teleconference in December 2023, claiming that there were around 10 million migrant workers in the country, mostly from the Caucasus, Central Asia, and Ukraine.

According to the FSB Border Service’s official data on the number of entries, the influx of foreigners to Russia in 2023 was somewhat higher than in previous years, particularly compared to the COVID-19 pandemic period. In 2019, 4.1 million expatriate workers came to Russia. This number dropped sharply in 2020 and 2021, to 1.08 million and 2.59 million, respectively. In 2022 and 2023, the influx of immigrants returned to previous levels (above 4 million) but remained below the 2019 level. According to Rosstat, the number of migrants who came to Russia from other countries in 2023 reached 560,400 people, which is 23% lower than a year earlier. This marks the lowest number since 2013, when 482,000 migrants entered the country.[15]

Aside from the pandemic, the recent decrease in immigration has been influenced by the war, as well as the associated rouble devaluation and uncertainty regarding the political and economic situation. Therefore, considering all these factors, travelling to, and working in Russia carries more risks than benefits. Immigrants fear that they could be forced to participate in mobilisation, which the state enforces in exchange for legal residence or a Russian passport. In September 2022, Putin signed a law allowing foreigners to be granted Russian citizenship after serving a year in the Russian army. This indicates that the Kremlin is interested in deploying them in the conflict. In January 2024, he signed another law that permits immigrants and their families to acquire citizenship in a simplified manner immediately after signing a military contract.

At the same time, following the terrorist attack on Crocus City Hall, the government tightened legislation regulating the presence and employment of foreigners in Russia. Border and workplace inspections have become significantly more stringent. According to media reports, this inter alia led to hundreds of Tajik citizens being stranded at airports in Russia by the end of April, prompting the Tajikistan Ministry of Foreign Affairs to deliver a protest note to the Russian ambassador in Dushanbe.[16] In several regions, such as Novosibirsk, Samara Oblast, and the Republic of Sakha (Yakutia), regulations have been enacted to prohibit immigrants from working in specific sectors, particularly public transportation (including taxi driving) and the food industry. These sectors, as well as municipal services and construction, have historically employed large numbers of immigrants. For example, according to Nikolai Kodolov, the chairman of the Moscow taxi drivers’ union Dobro, 20% to 30% of all taxi drivers in Moscow and up to 50% across Russia are immigrants.[17]

Following the terrorist attack, spontaneous acts of hostility towards immigrants have been observed in Russia. These included public protests, pressure on companies employing immigrants, and refusals to use services provided by them. This was coupled with the government’s propaganda campaign showing immigrant communities as hotbeds of terrorism. As a result, some countries from which large numbers of migrants used to come to Russia issued warnings to their citizens to avoid traveling there. Interestingly, this kind of warning has even been issued by Kyrgyzstan, a member of the Eurasian Economic Union, whose citizens theoretically are vested with the same rights in the Russian labour market as Russians.

Meanwhile, there is a growing need for immigrants in the Russian labour market. Currently, several economic sectors, including those crucial to the state and the Kremlin, such as the defence and energy sectors, are experiencing labour shortages despite wage increases.[18] According to data provided by the Russian Academy of Sciences, Russian companies are already short of around 4.8 million workers. This labour shortage is slowing economic growth, with unemployment reaching a historic low of 2.8% (first quarter of 2024). According to Elvira Nabiullina, the governor of the Central Bank of Russia, a lack of manpower a shortage is the main problem facing the Russian economy.

Another adverse phenomenon, as previously mentioned, is the wave of emigration, with people leaving the country for political reasons or to escape mobilisation. This not only reduces Russia’s population but also impacts its demographics, as primarily young people – of working and reproductive age – have left the country. According to available estimates, during the first year of the war, Russia experienced two waves of emigration: the first occurred after the Russian invasion began, and the second after mobilisation was announced in autumn 2022. These waves collectively involved 700,000–800,000 people, although up to half of them may have returned to Russia after a few months. These figures, however, are not reflected in official data.

Conversely, the demographic situation has improved as a result of of an increase in the number of Ukrainian refugees, especially from the illegally annexed Luhansk and Donetsk regions, and from people fleeing or being forcibly relocated as part of the so-called evacuations deeper into Russia from other parts of Ukraine. Although Russian statistics do not cover the annexed regions, the people living there are partly accounted for in immigration data. Since the beginning of the Russian invasion until the end of 2023, the UNHCR estimated the number of registered Ukrainian refugees in Russia at 1.2 million, and the number of entries from Ukraine into Russia at nearly 3 million.[19]

In recent years, the number of Russian passports issued to foreigners has surged, accompanied by a consistent liberalisation of legislation to facilitate this. Various measures have been introduced, particularly targeting Ukrainian citizens, including children kidnapped from Ukraine, as well as legal provisions related to military service. From 1992 to 2017, over 9 million foreigners were granted Russian citizenship.[20] In 2018, around 269,000 individuals were naturalised, with nearly 498,000 in 2019, 656,000 in 2020, and 691,000 in 2022. The highest number was recorded in 2021, with 735,000 passports granted, 51% of which were issued to Ukrainian citizens, mainly from the Donetsk and Luhansk People’s Republics, which Russia later illegally annexed. In total, approximately 12 million people were naturalised between 1992 and 2022.[21] This extensive naturalisation has been used to improve population statistics. Despite negative demographic indicators, the population has remained relatively stable since the 1990s. According to official data, in 2023, the population decreased by only around 1 million as compared to 1990. This stability is largely an effect of the mass naturalisation of foreigners.

Prospects: consequences of the war and for the economy

Given the official data and forecasts on Russia’s demographic situation, it is expected that its population will continue to shrink in the coming years. According to Rosstat’s medium projection, the Russian population will be 138.8 million by 2045, while the low projection estimates it at 130.6 million by the same year.[22] Similarly, the UN expects the population to decrease by 4.8 million by 2035 (bringing it down to 141.1 million) and continue shrinking to 135.8 million by 2050, amounting to a 10 million drop over 30 years. By 2100, the population is projected to reach 126.1 million. Unlike Rosstat’s figures, these UN estimates do not include the population of Crimea.[23]

In statistics, a sudden increase in population figures can be expected following the official inclusion of people from regions of Ukraine that are temporarily occupied by Russia (this has not yet been carried out). Due to such non-transparent practices, critically assessing Russian official data is becoming increasingly difficult, if not impossible. However, these tactics cannot reverse the adverse long-term demographic trends, which are exacerbated by the ongoing war. According to official statistics, the immediate consequences of the war, such as an excessive number of deaths and a decrease in births, are so far either invisible or less severe than expected. The demographic impact of the war, however, will become evident over the years, resulting not only from the high number of casualties but also from delays in family planning and reduced access to healthcare.

The visible decline in the indigenous Russian population and the influx of immigrants, who are increasingly being naturalised, are set to bring about a shift in the ethnic composition of the Russian population: ethnic Russians will still prevail, but their share of the population will decrease. This shift will be happening against the backdrop of ethnic and religious tensions and conflicts, to which Russian society is highly susceptible and which are already seen in Russia. Eventually, this will pose a challenge for Moscow, as it will become increasingly difficult to maintain control over regions with growing non-Russian communities, which will gradually drift away from the federal centre, both socially and politically. Consequently, internal migration will escalate rural depopulation and intensify urbanisation, particularly in the European part of Russia. These trends are already deepening the socio-economic and infrastructural gaps between regions, adversely affecting national cohesion.

Despite long-term demographic problems, Russia still has the resources to sustain its engagement in the war by replenishing its military personnel and conducting regular conscription. This perspective seems to be the most crucial for the Kremlin, as the war in Ukraine is its top priority. The Russian army’s high mobilisation potential results mainly from the fact that in the conscription-eligible generations (those aged 30 and older), each cohort saw the birth of 650,000 to 750,000 boys, with these figures recorded between 1995 and 2006. Therefore, the mobilisation of additional hundreds of thousands of soldiers, and even increasing the army size to 1.5 million, as announced by Defence Minister Shoigu, is feasible,[24] provided that the state budget has enough financial resources to pay them high wages. Financial motivation is one of the main pragmatic factors that encourage Russians to participate in the war and to procreate.

In the long run, Russia will face a problem with the deteriorating quality of human capital, which is due to the lifestyle of Russian men. They tend to abuse substances, particularly alcohol, more frequently and are more prone to accidents than Russian women and men in the West. Consequently, they also have a shorter lifespan. The war is gradually desensitising the Russian public to violence and contributes to their moral degradation. Consequently, there has been an increase in violence and crime, as reflected in official statistics. According to the Russian Ministry of Internal Affairs, over 589,000 serious and very serious crimes were committed in Russia in 2023, the highest figure since 2011.[25] The degradation of human capital will inevitably lead to a long-term decline in the economic and military potential of the state.

Regarding immigrants, whom Russia needs to compensate for the natural population decline and maintain its economic potential, fewer workers from the regions that were traditionally sources of workforce (Central Asia and the Caucasus) are likely to come to Russia due to its recent policies targeting them. These workers are already seeking destinations other than Russia and are migrating to Europe or the Middle East. In sectors where immigrants are being excluded due to newly enacted regulations, the cost of services will significantly increase, negatively impacting Russian consumers. In the longer term, however, the Kremlin will have to become more open to immigrants, whom it needs even more in the face of war – both in the local labour market and on the front lines.

So far, Moscow has demonstrated long-term adeptness in its policies toward immigrants, relaxing regulations when they were most needed. For instance, it admitted more immigrants after the pandemic and during the war, gradually simplified the rules for granting citizenship, and compensated for the natural population decline through naturalisation. This flexible approach, regardless of the current social climate in the country, is likely to continue. Although this will not reverse the negative trends, it will significantly mitigate them to prevent a demographic collapse. However, Russia’s plans could be thwarted by a severe economic downturn, which would discourage immigrants from Central Asia and the Caucasus from choosing Russia as a destination for economic migration.

[1] ‘Демографический ежегодник России’, Federal State Statistics Service, 2023, rosstat.gov.ru.

[2] ‘Социально-экономическое положение России’, Federal State Statistics Service, January–March 2024, rosstat.gov.ru.

[3] ‘Всероссийская перепись населения 2020 года’, Federal State Statistics Service, rosstat.gov.ru.

[4] This issue has been raised, for example, by Alexey Raksha – see 'Демограф Ракша: самые большие приписки населения – в Севастополе и на Северном Кавказе', Аналитический центр «Юг», 19 October 2021, eacs.center.

[5] ‘«Татар явно обделили»: демограф Алексей Ракша об итогах переписи, которая «провалена полностью»’, БИЗНЕС Online, 21 January 2023, business-gazeta.ru.

[6] ‘Birth rate, crude (per 1,000 people) - Russian Federation’, World Bank Group, data.worldbank.org.

[7] A lower result was seen in 2006, when the fertility rate was 1.31.

[8] The programme was originally set to run until 2016. The decision to extend it was made only at the end of 2015, which led to a decline in the number of births. These indicators also decreased as a result of the worsening economic situation in the subsequent years.

[9] ‘«Специальная военная операция» в Украине: отношение россиян. 13 волна (21-29 октября 2023)’, Russian Field, russianfield.com.

[10] A critical assessment of the 2020 and 2021 census methodology and results can be found, for example, in this interview ‘"Два самых лживых региона — Башкортостан и Саратовская область". Алексей Ракша объясняет результаты переписи’, Idel.Реалии, 18 January 2023, idelreal.org and in this text ‘"Если через десять лет в России установится демократический строй, мы увидим реальную численность татар". Об итогах переписи населения-2021’, Idel.Реалии, 17 January 2023, idelreal.org.

[11] Д. Сотников, Лондон оценивает потери РФ в Украине в 450 тысяч человек, Deutsche Welle, 28 April 2024, dw.com; D. De Luce, ‘Russia has suffered dramatic casualties in Ukraine, U.S. intelligence says’, NBC News, 12 December 2023, nbcnews.com.

[12] During the war in Afghanistan, the USSR lost 15,000 soldiers from 1979 to 1989, while in the Chechen Wars of 1995–1996 and 1999–2000, Russia lost a total of 11,000 military personnel.

[13] For more information, see M. Menkiszak, P. Żochowski, ‘Islamists and the 'Ukrainian trace'. The Moscow concert hall terrorist attack’, OSW, 23 March 2024, osw.waw.pl.

[14] ‘Рынок войны и труда: число легальных трудовых мигрантов в России в первой половине 2023 года сократилось, несмотря на острую нехватку рабочей силы’, 7 November 2023, re-russia.net.

[15] ‘Росстат раскрыл «портрет» мигранта в России Кто и с какими целями въезжает в страну из-за рубежа’, 22 July 2024, rbc.ru.

[16] И. Лакстыгал, Н. Гасымов, ‘Киргизия рекомендовала своим гражданам не ездить в Россию’, Ведомости, 3 May 2024, vedomosti.ru.

[17] ‘Изменения в миграционной политике: регионы вводят ограничения на работу мигрантов’, 7 May 2024, mkset.ru.

[18] ‘Russia’s War Economy Starves Crucial Oil Industry of Manpower’, The Japan Times, 8 May 2024, japantimes.co.jp.

[19] UNHCR data, The Operational Data Portal, data.unhcr.org.

[20] О.С. ‘Чудиновских, Статистика приобретения гражданства как отражение особенностей миграционной политики России’, “Вопросы статистики” 2018, no. 25, pp. 3–26, as in: voprstat.elpub.ru.

[21] The author’s own estimates based on: ‘Число получивших гражданство РФ снизилось в 2022 году впервые за три года’, 31 January 2023, rbc.ru.

[22] ‘Демография’, Federal State Statistics Service, rosstat.gov.ru.

[23] ‘ООН оценила демографические перспективы хуже Росстата Российское население будет быстрее «стареть» и сокращаться’, 24 June 2019, rbc.ru.

[24] It is unclear within what timeframe this plan (1.5 million soldiers) is to be implemented; however, by the end of 2024, the number of contract soldiers is to be increased to 745,000.

[25] Ж. Рофе, ‘В России зарегистрировали рекордное за 12 лет число тяжких и особо тяжких преступлений’, Deutsche Welle, 15 January 2024, dw.com.