Washington Summit – NATO's anniversary in the shadow of the war

Three themes were dominant at the NATO Summit in Washington (9–11 July): the reinforcement of allied deterrence and defence, support for Ukraine, and cooperation with the partners in the Indo-Pacific. NATO continues to adapt its command structure and the process of force generation for new regional defence plans. The most significant decisions concerned aid for Ukraine. Although Kyiv is yet to receive an invitation to join NATO, its integration path was described as "irreversible".

The decisions made at the summit regarding NATO's new role in supporting Ukraine are to serve as a "bridge" to eventual membership. These include NATO taking on tasks of coordinating military aid and the training of Ukrainian forces, along with a financial commitment of at least €40 billion annually for long-term support. Compared to previous documents, the allies have toughened their language on China in the Summit Declaration, identifying it as a decisive enabler of Russia’s war against Ukraine.

The 75th-anniversary NATO Summit in Washington had a different setting and political context to the previous meeting of the heads of state and government in Vilnius. The programme and accompanying events included a series of symbolic ceremonies, notably at the Mellon Auditorium, where the North Atlantic Treaty was signed in 1949. This was also the first summit with 32 members (following Sweden's accession) and the last with Jens Stoltenberg as Secretary General, as he will be succeeded by the former Dutch Prime Minister Mark Rutte in October.

The political context of the summit was largely shaped by recent elections in member states in Europe. While the new prime ministers of the United Kingdom and the Netherlands confirmed the continuity of their countries' NATO policies, the results of the parliamentary elections in France raise questions about how credible President Macron's stance may be. On top of that, former President Trump, whose critical views on the US's allied commitments cause concern among European allies, cast a shadow over the entire meeting, especially as his chances of winning the November election appear substantial.

Defence and deterrence: core task in the transformation process

Regarding allied defence and deterrence, the NATO Summit in Washington was designed as a review of the implementation of decisions taken in previous years. As such, it did not yield groundbreaking decisions on collective defence. Key decisions to strengthen allied defence and deterrence were made at the summits in Madrid (2022)[1] and Vilnius (2023)[2] – as a consequence of NATO's adoption of a new Concept for Deterrence and Defence of the Euro-Atlantic Area in 2020 and the recognition of Russia as the most significant source of direct threat to NATO's security in the 2022 NATO Strategic Concept.

In 2022–2023, the allies began transforming and modernising their forces to create a so-called New NATO Force Model and accepted three regional defence plans covering Northern, Central, and Southern Europe. These changes reflect NATO's shift in thinking about deterring Russia and defending the eastern flank – from demonstrating the ability to expel Russian forces from member states' territories to providing forces that would prevent Russia from encroaching on NATO territory.

The NATO Summit in the US should be seen as the first step in implementing the New Force Model and defence plans, allowing leaders to review actions undertaken so far and identify defaults. The Summit Declaration[3] emphasised areas for continuing the modernisation of the alliance's collective defence system: providing necessary forces, capabilities, resources, and infrastructure for new defence plans, conducting more frequent and large-scale exercises, increasing capacity in defence production, strengthening the command and control system, developing logistics and military mobility, reinforcing forward forces on the eastern flank, accelerating the integration of the space domain into planning, exercises, and operations, establishing the NATO Integrated Cyber Defence Centre, enhancing the protection of critical undersea infrastructure, investing in defence against weapons of mass destruction, and further improvements in interoperability. The decision to prepare "recommendations on NATO's strategic approach to Russia" for the next summit in The Hague is noteworthy.

With the introduction of regional defence plans and the enlargement of NATO to include Sweden and Finland, NATO's Force and Command Structure is being adapted on the alliance's northeastern flank. Along with other Nordic countries, Sweden and Finland will be subordinated to the allied Joint Force Command (JFC) in Norfolk, US, under the regional defence plan for Northern Europe. Whereas, the Baltic states, along with Poland, the other Central European countries, and Germany, fall under the JFC in Brunssum, the Netherlands. Discussions are ongoing about delineating areas of responsibility between the two commands in the Baltic Sea basin.

At the operational level, a multinational corps-level command for land operations on the northern flank will be established in Finland (similar to the Multinational Corps Northeast HQ in Szczecin). NATO Forward Land Forces (FLF) will also be deployed there – modelled on the allied presence in the Baltic states and Poland.[4] Additionally, a maritime component command will be established, rotating between Poland, Germany, and Sweden, responsible for commanding naval forces in the Baltic Sea.

The Washington Summit also provided an opportunity to review the progress of NATO's New Force Model, which aims to have over 800,000 troops at three tiers of readiness – within ten days (over 100,000), within 30 days (about 200,000), and within 180 days (at least 500,000). These forces should be ready to conduct land, naval, air, space and cyber operations. The first tier includes local forces from the northeastern flank and units from western allies deployed there. The second tier includes larger tactical formations at the division and corps levels, capable of rapid deployment to the conflict region. While the summit declared the readiness of 500,000 troops, specific assignments to the tiers were not provided.[5] Additionally, on July 1, NATO activated new rapid reaction forces (Allied Reaction Force, ARF), with components provided on a rotational basis by the largest member states. It will be challenging for NATO to verify the actual levels of the quality of equipment, manning, and the readiness of individual units. They do not undergo a certification process (with the exception of the ARF), and without exercises and inspections, NATO will still rely solely on the declarations of member countries.[6]

In Washington, NATO also confirmed the integration of the US base in Redzikowo into NATO's Ballistic Missile Defence (BMD) system. The US-German declaration on the temporary deployments of US long-range missile capabilities in Germany starting from 2026 was an important signal for strengthening deterrence. In the future, the US plans to deploy SM-6, Tomahawk, and hypersonic missiles in Germany.

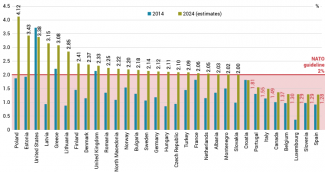

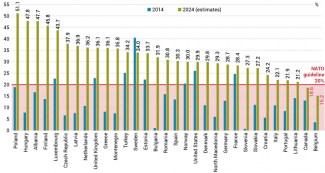

2024 marks a significant milestone in NATO defence spending, as a decade ago in Newport, members committed to increasing it to 2% of GDP over ten years. This year, 23 allies have met this pledge (see Appendix).[7] Major allies that have not yet met the 2% goal include Canada (1.37%), Italy (1.49%), Spain (1.28%), and Belgium (1.3%). Canada's inadequate defence spending is a cause for concern, given its role in expanding NATO forces in Latvia to brigade level. Additionally, some members met the Newport commitment at the last minute by allocating additional funds in the final months before the summit (e.g., Denmark and Norway). However, there has been a noticeable increase in equipment spending, that is, on the modernisation of the armed forces of NATO countries. Except for Canada and Belgium, all members allocate a minimum of 20% of their defence budget to acquiring new armament and military equipment (see Appendix).

Among the allies gathered in Washington, there was no consensus on setting a new defence spending target for 2030 and beyond, despite calls from Poland and the Baltic states for a goal of 2.5% or 3% of GDP. Without further increasing defence spending, it will be difficult to reconcile generating capabilities for collective defence with maintaining military support for Ukraine. Part of the way out of this is formed by the commitment made in Washington to strengthen defence industrial capacities (NATO Industrial Capacity Expansion pledge). This includes developing national plans to expand the defence industry, accelerating multinational joint procurements and implementing common standards, removing barriers to trade and investment, and ensuring the security of supply.

NATO-Ukraine: a bridge to membership or political evasion?

As expected, the summit did not yield a political breakthrough in accelerating Ukraine’s NATO accession process. The lack of consensus among allies on issuing a formal invitation to Kyiv mainly stems from concerns shared by the majority of member states that it could effectively extend NATO security guarantees to Ukraine during the war. Among the largest member states the US and Germany are notably opposed to this. Therefore, the summit focused on preparing a long-term NATO support programme for Ukraine.[8] While it cannot match the benefits of full NATO membership, the alliance's assistance offer to Kyiv is significant. Its greatest added value lies in NATO's decision to take over from the US the role of coordinating armament and military equipment deliveries to Ukraine (NATO Security Assistance and Training for Ukraine, NSATU). This also includes coordinating training programmes, organising logistics, and potentially repairing equipment. In practice, this signifies an agreement for the use of NATO’s structures and experience to align Ukraine’s defensive needs with the resources available from states willing to provide military assistance. The Ukraine Defense Contact Group (the so-called Ramstein Group, which will still be led by Washington) already includes over 50 countries and the European Union. Around 700 officers will be assigned to NSATU for coordination tasks, serving under a new command being established in Wiesbaden, Germany (NATO Command for Ukraine), transformed from the existing American structures operating under the US Army Europe command structure.

NSATU will streamline various national programmes and the EU-led training programme for Ukrainian forces. There are numerous initiatives, some of which (e.g., delivery of different types of fighter jets) require a critical review to avoid duplication and ensure the optimal use of the limited resources of Ukraine and the supporting states.

The summit’s decision will also help those allies currently bearing the main responsibility for the security and management of logistical hubs, the largest of which is in Poland. This decision means that NATO will now handle their funding and operational security.

An important addition to the assistance package is the summit’s approval of the full activation of the NATO-Ukraine Joint Analysis, Training, and Education Centre (JATEC) in Bydgoszcz, Poland, which is soon to reach full operational readiness (currently, only a limited number of staff officers have been assigned). JATEC will significantly contribute to how the lessons learnt from the war in Ukraine are analysed as well as to streamlining the training system and improving the interoperability of the Ukrainian Armed Forces with their allied counterparts. This last task will help Kyiv better prepare to meet NATO requirements until the political conditions for considering a date to start accession talks emerge.

At the US's initiative, NATO also announced the Secretary General’s appointment of a senior NATO representative in Kyiv. This official is expected to act as a sort of spokesperson for NATO–Ukraine cooperation and a political liaison between NATO and the Ukrainian authorities, and will also lead the NATO Representation in Kyiv.

To broaden and strengthen the alliance’s assistance, the summit placed significant political importance on the bilateral security agreements concluded with Ukraine in recent months (over 20 such agreements have been signed so far). Formally separate from NATO, these agreements reinforce the long-term nature of support for Ukraine during the war. At the summit’s conclusion, President Biden organised a special session with the European Union and all the countries that responded to last year’s G7 call for such agreements (the call has been supported by 32 countries). A new political format, the “Ukraine Compact”, was established, adding another element of durability to the international commitments to Ukraine.[9]

The agreement reached on a political pledge attached to the Summit Declaration (Pledge of Long-Term Security Assistance for Ukraine) was a notable success of the summit. This guarantees substantial funds (€40 billion annually, half of which will come from the US) for military aid to Ukraine. The adoption of this pledge was not certain, with Hungary refusing to participate in this project from the outset and some other countries showed limited enthusiasm to make financial commitments within the NATO framework. Ultimately, the allies agreed to count various military support expenditures, including NATO Trust Funds for Ukraine, towards the pledge, even if they include non-lethal aid, and that member states will be required to submit implementation reports twice a year. The long-term value of this pledge is weakened by a clause that mentions a review of this initiative at the next summit in The Hague in 2025.

Given these circumstances, the declaration of the joint NATO-Ukraine Council,[10] attended by President Zelensky, focused on publicising the decisions of the summit and bilateral security agreements. Despite Moscow’s efforts to undermine the allies' determination to support Ukraine, seen in massive missile attacks on Ukrainian cities on the eve of the summit, the barbaric destruction of hospitals in Kyiv seemed to have had the opposite effect. New military aid packages were announced at the summit, with a focus on air defence systems. The package announced by the US and a group of allies is particularly important. This includes four medium-range Patriot air defence systems and one SAMP/T system. These attacks also countered initiatives launched by opponents of closer Ukrainian integration (e.g., an open letter by American experts[11]), and helped countries that argued for stronger language on membership – the summit agreed on a passage about the “irreversibility” of Ukraine's accession path.

Despite the clear gap between expectations (an invitation to membership) and the summit's outcome, Kyiv publicly tried to emphasise the positive aspects of the decisions – the received commitments to military aid. President Zelensky and his team used the meeting to mobilise the Western partners, particularly the US, to increase and expedite deliveries of the most needed weapons (primarily air defence systems and F-16 fighters) and to gain their approval to strike military targets deep inside Russian territory. These efforts align with initiatives taken in recent months across various forums, confirming the Ukrainian political elite’s determination to defeat Moscow on the battlefield and end the conflict on their terms, rather than entering into peace negotiations with Russia.

Partnership with Indo-Pacific countries – a project under construction

The NATO Summit in Washington marked a continuation in the development of partnerships with selected Indo-Pacific nations (AP4: Japan, South Korea, Australia, and New Zealand). For the third time, allies met with their leaders (Australia was represented by its Deputy Prime Minister), along with representatives from the European Union (the President of the European Council and the President of the European Commission). Contrary to expectations, efforts to publish a joint declaration proved unsuccessful. The Summit Declaration mentions the intensification of cooperation through so-called flagship projects in areas such as support for Ukraine, cybersecurity, combating disinformation, and technology. However, these are not new fields; there was a lack of political will to venture into new initiatives (e.g., creating a separate structure for exchanging classified analyses). The Biden administration decided not to expend political capital on disputes regarding the implications of operational theatre linkages between Europe and the Indo-Pacific. Unjustified concerns still exist in Europe that a closer NATO partnership with the AP4 might generate military commitments, even if Washington does not expect this to be the case. No progress was made in expanding the political framework for dialogue and cooperation. Attempts to unblock the decision to establish a NATO liaison office in Tokyo also failed.

Perhaps more significant for the partnership's prospects with AP4 was the new, more robust language in the Summit Declaration regarding China’s policies. NATO rejected Beijing’s attempt to position itself as a neutral party in Russia's war against Ukraine. The Declaration openly accuses China of helping Russia, including through supplying critical components for Russia's defence industry and providing political and propaganda support for Moscow. NATO demands that China cease these activities and warns that their continuation will negatively impact Beijing’s interests and reputation.

The very fact that another NATO–AP4 meeting was held during the summit has significant political importance. Public statements by Indo-Pacific leaders in Washington confirmed their strategic interest in cooperation with NATO – weakening arguments against the NATO–AP4 partnership. The course of the meeting and AP4 leaders' statements indicated the presence of a growing convergence of views about policies on Russia and China. This should yield results in the coming months, especially as both the Sino-Russian alliance and increasing tensions in the Indo-Pacific region will require more ambitious cooperation projects. The cohesive message of NATO and the AP4 solidarity mitigated some political damage caused by Hungarian Prime Minister Orban's visit to China on the eve of the summit.

What was missing?

Some issues not covered in the Washington Summit Declaration, or mentioned only in very general terms, are just as important as the decisions which were announced. The absence of references to Georgia's membership aspirations sends a clear signal to the government in Tbilisi that their policies are viewed negatively by NATO. Repeating the language from the Vilnius Summit on nuclear policy illustrates the lack of enthusiasm in many member countries for rapid changes in NATO’s nuclear deterrence policy, including nuclear sharing. In the part of the declaration devoted to Russian hybrid attacks (such as sabotage, provocations, malicious cyber activities, etc.), further steps to be taken individually by member countries or NATO in response to these threats are mentioned but not publicly defined.

APPENDIX

Chart 1. NATO countries' defence expenditure as a share of GDP

Source: NATO.

Chart 2. Equipment expenditure as a share of defence expenditure

Source: NATO.

[1] J. Gotkowska, J. Tarociński, ‘NATO after Madrid: how much deterrence and defence on the eastern flank?’, OSW, 5 July 2022, osw.waw.pl.

[2] J. Gotkowska, J. Graca, ‘NATO Summit in Vilnius: breakthroughs and unfulfilled hopes’, OSW, 13 July 2023, osw.waw.pl.

[3] NATO, ‘Washington Summit Declaration’, 10 July 2024, nato.int.

[4] MoD (Finland), ‘NATO defence ministers support objectives of Finland's NATO integration’, 14 June 2024, defmin.fi.

[5] NATO, ‘NATO Secretary General: “Our most urgent task at the Summit will be support to Ukraine”’, 5 July 2024, nato.int.

[6] J. Deni, ‘The new NATO Force Model: ready for launch?’, NATO Defense College, 27 May 2024, ndc.nato.int.

[7] NATO, ‘Defence Expenditure of NATO Countries (2014-2024)’, 17 June 2024, nato.int.

[8] R. Pszczel, ‘How to win the war and join NATO? The key role of Ukraine’s partnership with the Alliance’, OSW, 28 June 2024, osw.waw.pl.

[9] The White House, ‘President Joe Biden Launches the Ukraine Compact’, 11 July 2024, whitehouse.gov.

[10] NATO, ‘Statement of the NATO-Ukraine Council’, 11 July 2024, nato.int.

[11] M. Berg, ‘Ukraine ‘bridge’ to NATO could be dangerous, experts warn’, Politico, 3 July 2024, politico.com.