Turkey: a looming demographic crisis

After many years of rapid population growth, Turkey’s demographic future hangs in the balance. The record-low birth rate in 2023 and the changing age structure indicate that Turkish society is entering a stage of ageing typical for highly developed countries. Regional disparities in this respect are also deepening: the country’s poorer, south-eastern region has a much higher fertility rate and a younger population, while the northern regions along the Black Sea have a higher average age. These current trends reflect deeper transformations taking place in Turkey, driven by internal migration and modernisation processes related to factors such as urbanisation and cultural changes; they are also the product of many years of economic uncertainty. Simultaneously, growing numbers of mostly young people have been leaving the country. These developments herald an imminent demographic crisis that will negatively impact the Turkish economy and necessitate a major adjustment of social policy.

The end of the demographic boom

Until recently, Turkey was notable for its rapid rate of natural increase. Its population, which stood at 27.5 million in 1960, soared to almost 45 million by 1980. By 2000, the country had 64.1 million inhabitants, a number that increased to 83.3 million in 2020. However, the latest demographic data published by the Turkish Statistical Institute (TÜRKSTAT) following the annual census suggests that this upward trend has slowed significantly. The data show that more than 85.3 million people lived in Turkey in 2023, with the year-on-year population growth rate hitting an all-time low of 1.1‰, down from 7.1‰ just a year earlier and as high as 14.7‰ in 2018. Moreover, a record low number of children (958,000) were born in the country in 2023, and the fertility rate fell to 1.51 live births per woman. Since 2017, this rate has remained below 2.1 – the level considered necessary for replacement-level fertility. While these figures still place Turkey above the EU average (1.46 according to Eurostat data for 2022), they are lower than those in several EU member states, including France, Bulgaria, and Romania.[1] According to the UN’s demographic forecast, Turkey’s population will continue to grow until 2047, peaking at 91.4 million, but then it will start shrinking rapidly, projected to fall to 65.3 million by 2100.[2] This means that the ruling elite’s goal of a 100 million-strong Turkey will not be achieved in the foreseeable future.

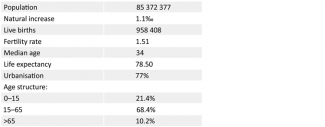

Table. Turkey in 2023: demographic summary

Source: The Turkish Statistical Institute.

At this point, Turkish society is still younger than those in Europe, but there are clear indications that it is ageing. The median age rose from 25.8 years in 2000 to 34 years in 2023, compared to 44.5 years in the EU.[3] In 2023, children under the age of 15 made up 21.4% of the total population, while people over 65 accounted for 10.2%. However, according to TÜİK’s projections, due to the falling birth rate, the percentage of these two groups will draw level as early as the 2040s; from then on, the proportion of senior citizens will surpass that of younger individuals and continue to widen.[4] This trend will also be influenced by rising life expectancy: from 72.6 years for those born in 2002 to 78.5 years for the 2022 cohort.[5]

This concerning demographic data reflects ongoing societal changes. High urbanisation (77%[6]) is leading to lifestyle shifts and the erosion of traditional behavioural patterns. The average number of years spent in education is increasing, and young Turkish people are marrying and starting families at progressively later ages[7]. The average age of mothers at first childbirth rose by 4.7 years from 2010 to 27 in 2023. Families are becoming smaller, with the average household size steadily decreasing and the proportion of one-person households.[8] Another factor contributing to the falling birth rate is the persistent economic crisis, which, combined with high inflation (71.6% year-on-year in June 2024 according to official data), has worsened living conditions and likely influenced decisions about childbearing.

A populous south, a desolate north

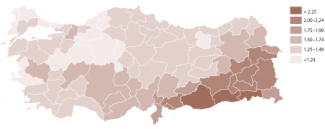

Data from TÜİK reveals significant demographic diversity across Turkey. The highest fertility rates are found in the south-eastern provinces (see Map), which have a high proportion of Kurdish and Arab populations: Şanlıurfa (3.27), Şırnak (2.72), and Mardin (2.40). In contrast the lowest fertility rates are in the northern Black Sea region, with the provinces of Bartın (1.13), Zonguldak, and Karabük (1.14 each). The south-east has the youngest population: the median age in the provinces of Şanlıurfa and Şırnak is 21.2 and 22.7 years, respectively. By contrast, the highest median age was recorded in the Black Sea provinces of Sinop and Giresun: 42.8 and 42.2 years, respectively.[9] The south-east also has the largest average household size,[10] the highest proportion of children, and the lowest average age of mothers at birth.[11] Region-specific data does not allow for direct conclusions about the country’s ethnic structure, as questions about ethnicity has been consistently left out of the censuses. However, the idea about a growing Kurdish and Arab population and the resulting changes to Turkey’s ethnic make-up has been a recurring theme in nationalist discourse.

Map. The fertility rate by province in 2023

Source: The Turkish Statistical Institute, data.tuik.gov.tr.

Rural areas across the country, weakened by internal migration, are at risk of depopulation. The majority of Turkish people live in large cities located in the west; with Istanbul – the country’s largest metropolis with 15.6 million residents – housing almost a fifth of the total population.[12]

Migration-related dilemmas

Turkey has experienced both immigration and emigration. The former has been driven by Turkey’s relatively stable political situation compared to the rest of the region and by its proximity to Europe, which is often seen as the final destination. Turkey is frequently one of the stops along the way rather than the end point. According to the Turkish migration authority, in July 2024, the number of legal migrants in the country totalled 4.4 million, representing more than 5% of the population. The largest group, numbering 3.1 million, were refugees under temporary protection who had arrived after the civil war broke out in Syria in 2011. An additional 1.1 million had residence permits (mostly Turkmen, Russian, and Iraqi nationals), while 228,000 (mainly Afghans) were under international protection.[13]

Increasing the influx of foreigners might seem like a potential solution to Turkey’s demographic challenges. However, this is not acceptable to much of the population, which is wary of opening the country to newcomers, particularly those from the Middle East. The migration issue has generated serious social tensions, leading to violent street incidents that escalated into riots and attacks on asylum seekers, notably those from Syria.[14] Political figures have repeatedly called for their deportation. Since 2021, the number of Syrians in Turkey has been steadily declining,[15] partly due to the migration authority’s campaign of voluntary returns to their country of origin.[16] Additionally, the Syrian refugee population in Turkey is also facing a demographic downturn.[17]

Another factor adversely affecting the country’s demographic situation is the growing interest in emigration among Turkish citizens, particularly young people. Emigration began to rise after 2020, but 2023 marked a record year for departures: 715,000 people left the country permanently, including 291,000 Turkish citizens, representing a 53-percent increase from the previous year. The majority of emigrants were aged 25–29 and 30-34.[18] In 2023, as many as 114,000 Turkish nationals received their first residence permits in the EU, with Germany (31,000), Poland (20,000), and the Netherlands (13,000) issuing the most permits.[19] Turkish nationals also applied for asylum in the EU more frequently, submitting 90,000 asylum applications in 2023almost 40,000 more than in 2022 – making them the third largest group of applicants.

The powerless government

President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, who has repeatedly encouraged women to have “at least three children”, called the latest demographic statistics “worrying” and warned that the crisis in this area poses an “existential threat to the state.” Until now, Turkey’s young and rapidly growing population has been one of its key assets, especially in the eyes of foreign investors. A population decrease, if the situation unfolds according to the UN’s projections, could have a long-term negative impact on the country’s economy and its position on the international stage. A demographic decline would also pose a challenge for the country’s military, which is NATO’s second largest force with 481,000 personnel.[20] The Turkish armed forces rely on conscription; men aged between 20 and 41 are subject to compulsory military service.

The ageing population will place a greater burden on the social security system, particularly due to the growing number of pensioners. They are already a significant pressure group and an important segment of the electorate; their needs, such as the indexation of pensions, have increasingly featured in the political mainstream. This, in turn, presents a challenge to Minister Mehmet Şimşek’s pursuit of fiscal discipline. The ruling Justice and Development Party’s (AKP) failure to deliver the expected pension raise was identified as one of the reasons for its defeat in the March 2024 local elections.

However, the discussion about the demographic crisis is only just beginning and has not yet become a permanent feature of Turkish public debate. Family-friendly policies and strategies to contain or at least mitigate the potential effects of the demographic downturn have not yet been priorities for the current government. The Ministry of Family and Social Services has promised to develop a comprehensive programme to support mothers in the labour market through measures such as opening public nurseries and kindergartens. At the same time, the government continues to view the promotion of ‘traditional values’ and the ‘protection of the family’ as potential ways to reverse these negative trends.[1] Birth Statistics, 2023, TÜİK, 15 May 2024, data.tuik.gov.tr.

[2] ‘World Population Prospects: The 2024 Revision’, United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division, population.un.org.

[3] ‘EU median age increased by 2.3 years since 2013’, Eurostat, 15 February 2024, ec.europa.eu.

[4] Elderly Statistics, 2023, TÜİK, 27 March 2024, data.tuik.gov.tr.

[5] Life expectancy at birth, total (years) – Turkiye, The World Bank, data.worldbank.org.

[6] Urban population (% of total population) – Türkiye, The World Bank, data.worldbank.org.

[7] Marriage and Divorce Statistics, 2023, TÜİK, 22 February 2024, data.tuik.gov.tr.

[8] Statistics on Family, 2023, TÜİK, 15 May 2024, data.tuik.gov.tr.

[9] Birth Statistics, 2023, op. cit.

[10] Statistics on Family, 2023, op. cit.

[11] Birth Statistics, 2023, op. cit.

[12] The Results of Address Based Population Registration System, 2023, TÜİK, 6 February 2024, data.tuik.gov.tr.

[13] ‘Başkanlığımızı Hedef Alan Mesnetsiz İddialar Hakkında Basın Açıklaması’, Göç İdaresi Başkanlığı, 16 July 2024, goc.gov.tr.

[14] Vide the July 2024 riots in Kayseri which were triggered by rumours that a Syrian refugee had sexually abused a child. These events led to anti-Turkish demonstrations in the areas of northern Syria controlled by the Turkish armed forces. V. Kuşçuoğlu, ‘Violent protests target refugee community in Turkey’s Kayseri after alleged sexual assault on minor’, Bianet English, 1 July 2024, bianet.org.

[15] Temporary protection, Presidency of Migration Management, 25 July 2024, en.goc.gov.tr.

[16] Human rights organisations have questioned the ‘voluntariness’ of returns to Syria. See ‘Syrians Face Dire Conditions in Turkish-Occupied ‘Safe Zone’’, Human Rights Watch, 28 March 2024, hrw.org.

[17] Ö. Özkızılcık, ‘Sessiz istila yok; Suriyelilerin doğum oranları da nüfusu da azalıyor’, serbestiyet, 5 June 2024, serbestiyet.com.

[18] International Migration Statistics, 2023, TÜİK, 19 July 2024, data.tuik.gov.tr.

[19] First permits by reason, length of validity and citizenship, Eurostat, 29 July 2024, ec.europa.eu.

[20] ‘Defence Expenditure of NATO Countries (2014-2024)’, NATO, 17 June 2024, nato.int.