Russia’s weak spot: the financial sanctions are working

Since December 2023, the US administration has been increasing its pressure on Russia’s financial sector and its foreign partners. This has made it progressively more difficult for the Russian Federation to pay for imported goods and services. Reports from Russian media and businesses also indicate that several Chinese banks have ceased their cooperation with Russia due to concerns over US secondary sanctions. Nonetheless, these challenges have not yet led to any significant alterations to Russia’s foreign trade. According to the Central Bank of Russia (CBR), in the first eight months of 2024, the value of imports fell by approximately 8% year-on-year, while exports declined by more than 1%. This relatively modest reduction suggests that Russian entities, in collaboration with their foreign partners, particularly those in the Global South, continue to find ways to circumvent the sanctions. However, the costs of importing goods are increasing and delivery times are lengthening. Consequently, inflation continues to rise, further exacerbating Russia’s economic woes.

Rising US pressure on Russia’s financial market

Even though the West has targeted the Russian Federation with financial sanctions since 2014, Russian entities have been relatively effective at developing mechanisms to circumvent them. Export companies have been particularly active in this regard after they were compelled to reduce transactions in dollars and euros and switch to settlements in roubles and other national currencies, including the yuan, the dirham, and the rupee. However, even these businesses have encountered several difficulties with international payments. For instance, in 2023 they accumulated approximately $40 billion worth of rupees in Indian banks, for the oil they had supplied. According to reports from both sides, most of these transactions have now been settled, partly through investments in India and the use of third-country currencies.

Since autumn last year, the US administration has sought to complicate international settlements for Russian entities, primarily by imposing restrictions on additional financial institutions and discouraging the financial sectors of third countries from cooperating with Russia. A crucial development occurred in December 2023, when the US Treasury Department was granted the authority to impose secondary sanctions on third-country entities that assist Russia’s military-industrial base, restricting their access to the US financial market.In addition, the US has added Russia’s major financial institutions to its sanctions lists. These include the Moscow Exchange and the National Clearing Centre under its control (June 2024), the National Payment Card Sy stem, which issues MIR bank cards (February 2024), and several Russian banks, including the VTB’s Shanghai branch. Washington has also intensified its monitoring of the international activities of Russian entities; as a result, it has uncovered various schemes to evade sanctions involving companies from third countries. Consequently, an increasing number of businesses from China, Turkey, and the United Arab Emirates have been added to the US sanctions lists. The EU has begun taking similar measures, although the number of third-country entities subject to EU sanctions is much smaller.

The consequences of tighter sanctions

Successive rounds of sanctions have led to increasing difficulties with payments for Russian imports, impacting even goods and companies not subject to Western sanctions. The most serious difficulties have been reported by importers of cars, electronics, clothing, and Indian steel. Foreign banks, primarily those from China,Turkey, Armenia, and Kazakhstan, have increasingly refused to accept payments from Russia. While the exact scale of unprocessed payments is difficult to estimate, media reports indicate that most funds are now being reimbursed to the payers. The most severe restrictions apply to direct payments in yuan from Russia to China. In late August this year, problems also began affecting yuan payments made through third countries; for example, banks in the United Arab Emirates rejected transactions for imports of Chinese electronics when a Russian company was the end customer. It should be noted that the rouble is the primary settlement currency for Russian imports (according to the Central Bank of Russia, last June nearly 43% of all transactions were made in this currency), followed closely by the yuan, which accounts for around 40% of payments.

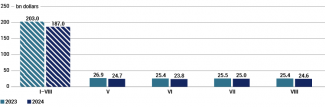

The restrictions have primarily affected small and medium-sized Russian companies. Large businesses, with their extensive legal and accounting resources, continue to find new channels for international settlements. As a result, there has been no significant decline in imports to Russia thus far. However, it is important to note that payment issues have been mounting since late July, while data on trade volumes for this period has yet to be released. Russia’s balance of payments shows that in the first eight months of 2024, imports were approximately 8% lower than the year before (see Chart 1). Customs data from the largest suppliers to the Russian market also indicates that changes in trade have been minimal.

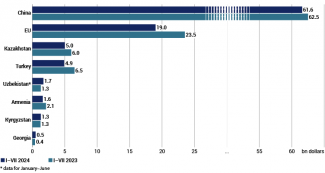

The largest declines in exports during the first seven months of 2024 (approximately 20% year-on-year) were reported by Turkey, Armenia, the EU, and Kazakhstan. In contrast, shipments to Russia from Georgia, Kyrgyzstan, and Uzbekistan increased during this period (data for H1), although the share of these countries in Russian imports remains small. However, this rise may suggest that these nations have expanded their role as channels for Russia to bypass the sanctions. Meanwhile, the value of Chinese exports to Russia in the first eight months of 2024 remained largely unchanged compared to the same period last year (see Chart 2).

China’s position between Russia and the West

Beijing’s stance is crucial to the effectiveness of the West’s tightening financial sanctions. Following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, China has become Russia’s primary economic partner. In the first half of 2024, it accounted for approximately 40% of Russia’s imports and over 30% of its exports. Moreover, the yuan has become the principal settlement currency for Russia’s foreign trade and the sole reserve currency for the Central Bank of Russia. China is keen to maintain its influence in Russia, as any significant reduction in trade with its northern partner would lead to economic losses and reputational damage by highlighting the effectiveness of US policy and casting doubt on the yuan’s potential as an alternative to the dollar. However, for China’s most globalised financial institutions, US secondary sanctions are highly damaging, which has increased interest in alternative, though often less efficient, methods of trade settlement.

Despite public expressions of support from the Communist Party, Chinese businesses, including state-owned banks, have been striving to comply with US regulations as they seek to mitigate the negative impact on China’s economy. Large Chinese players have been particularly eager to avoid the risk of sanctions due to their involvement in the relatively insignificant Russian market; therefore, they have been reducing their exposure and scaling back their activities in Russia. For instance, since last April, the Russian branch of the Bank of China has reduced its net assets by approximately 40%. Furthermore, after the Moscow Exchange (MOEX) was added to the US sanctions list, it ceased acting as its bank for clearing yuan transactions. It was replaced in this role by the local branch of the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China, which may also withdraw if the US licenses allowing it to temporarily cooperate with MOEX expire on 12 October.

Chinese banks have also opted to introduce more stringent vetting of entities involved in cross-border transactions. Consequently, the clearing process has become significantly longer; according to various media reports, some payments have not been completed at all. Many institutions have begun treating all yuan passing through the Russian financial system as ‘tainted’ and have, at least temporarily, suspended processing payments from Russian entities altogether.

Until June, the Shanghai branch of the Russian-based VTB played a key role in bilateral trade settlements. However, after it was subjected to sanctions, Chinese state institutions, including the Bank of China, terminated their cooperation with the bank. Smaller banks located in border regions, whose links to the global financial system and transparency are limited, have reportedly stepped in to partially fill the gap left by larger, Beijing-controlled entities. Nevertheless, they lack the necessary resources and organisational capacity to manage such operations on a sufficient scale.

An analysis of China-Russia trade since the beginning of this year suggests that payment issues and uncertainty surrounding the implementation of additional US sanctions may have resulted in a reduction in the sales of sensitive goods (including large trucks, excavators, lathes, and vertical machining centres) from China to Russia and caused a temporary decline in overall trade between the two countries. In March and April, the total value of Chinese exports to Russia declined by double digits year-on-year. However, in the following months, it returned to last year’s levels; in August, it was even 10% higher than the previous year. This suggests that entities on both sides of the border continue to find ways to settle their transactions.

One of the solutions Russia has employed in its trade with China and other partners is to use third countries to register subsidiaries with bank accounts located outside Russia or enlist intermediaries who formally have no connections to Russia. Other common methods include platforms that connect importers with exporters holding ‘clean’ yuan in China, as well as illegal solutions such as payments in cash, cryptocurrency, and gold; there have even been attempts to establish a barter system.

The effectiveness of financial restrictions

In recent months, US secondary sanctions have become one of the primary tools to deter third countries from supporting Russia in its efforts to circumvent Western restrictions. The threat of cutting off banks from China, Turkey, and the Gulf states from the US financial market, which remains crucial for them in trade and investment settlements, has proven particularly effective. As a result, large, reputable institutions have moved to minimise the risk of cooperating with Russia, sometimes even pre-emptively avoiding any dealings with Russia-linked entities. Although alternative settlement mechanisms continue to emerge, the costs of these operations are increasing, and delivery times to Russia are lengthening.

Due to the yuan’s importance in the Russian economy, the sanctions have had a significant impact on Chinese-based global entities, but in the long term, China may ultimately benefit the most from Russia’s difficulties. The tighter restrictions have not resulted in a sustained decline in Russia’s trade with China, indicating that both countries have managed to develop resilient financial mechanisms. Large Chinese businesses and their affiliates are likely to replace smaller Russian importers. Meanwhile, reduced competition is expected to drive up the prices of imported goods.

The rising costs of imports are driving inflation, which the Central Bank of Russia has been struggling to control since last year (the key interest rate now stands at 19%). Officially, annual inflation in Russia exceeded 9% in late August, but research by the Romir Institute, which uses a much broader basket of goods than Rosstat, suggested that the actual increase in prices during this period was over 21%.

Further steps to tighten the financial sanctions by adding more Russian banks (such as Gazprombank) to sanctions lists, including those maintained by the EU (while also pressuring European banks to withdraw from Russia), alongside efforts to monitor compliance with the restrictions and extend these to include third-country partners, will negatively affect Russia’s financial stability, particularly as these measures increasingly target payments for Russian energy exports.

Chart 1. The value of goods imported to Russia

Source: CBR Balance of Payments, cbr.ru.

Chart 2. The value of exports from selected countries to Russia

Source: Eurostat and the national statistical offices of Turkey, Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Armenia, Georgia, and China.