An alternative alliance: will Germany’s extreme right and extreme left parties join forces?

Pro-Russian, anti-EU, and anti-American parties – the far right Alternative for Germany (AfD) and the far left Sahra Wagenknecht Alliance (BSW) – have been gaining ground in Germany. In the September elections to the Landtags in Saxony and Brandenburg, these two parties together garnered more than 40% of the vote. In Thuringia, they hold a majority in the Landtag.[1] Regarding their platforms, they share numerous positions, particularly concerning foreign policy: they oppose continued support for Ukraine and demand the withdrawal of US troops and nuclear weapons from Germany. In domestic affairs, they have considerable potential for cooperation, as both advocate limiting the inflow of migrants, support state media reform, and hold similar views on climate policy.

The primary differences in their platforms are related to their vision of the economy and the extent of state interventionism. The AfD advocates a liberal approach, whereas the BSW promotes statism and a more radical regulatory stance. However, these divergences are not so profound as to preclude potential cooperation in the future. Thus far, BSW leaders have expressed their intention to maintain a so-called cordon sanitaire around the AfD and have ruled out the possibility of forming a coalition with this party, primarily because AfD politicians have been placed under surveillance by German counterintelligence. Nevertheless, it remains more likely that the two parties will collaborate on an ad hoc basis during specific votes in the Landtags or in the Bundestag, rather than establish a joint government at the federal state level. With respect to voting in the Bundestag, both parties will need to secure sufficiently strong results in the 2025 election to block decisions which require a two-thirds majority. Such a scenario would be unprecedented in Germany’s history and would demonstrate the strength of both the AfD and the BSW.

Both parties operate at opposite extremes of the political spectrum, which would suggest that they share little in common beyond their intent to build political capital by opposing the unpopular government led by Chancellor Olaf Scholz (SPD). They originate from radically different ideological backgrounds, and their electoral platforms are difficult to compare, primarily due to the ambiguity of the proposals they present.

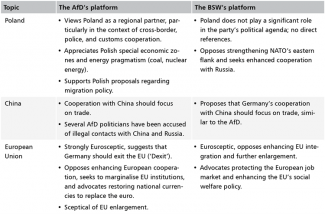

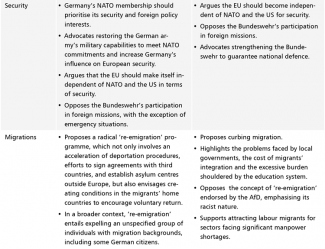

The AfD’s platform frequently diverges from the political demands voiced by the party leaders and omits the most controversial concepts expressed during rallies or on social media. The BSW’s leader, by contrast, highlights that, due to her party’s short history, its platform currently rests on a general framework of ideas. The two parties outlined more specific proposals in their manifestos released ahead of the Landtag and European Parliament elections (see Appendix 1 for a comparison of their platforms). Despite these challenges, certain fundamental similarities can be identified between their proposals, particularly in the areas of foreign, migration, and climate policies.

Shared themes: Russia, migration, and climate

Both parties have achieved their highest level of support in Germany’s eastern federal states, however, it should be noted that, thus far, the BSW has not been successful in any election held in the western federal states, apart from the European Parliament election. In most of these states, it failed to surpass the 5% electoral threshold, with the exception of Bremen (5.6%) and Saarland (7.9%). A significant portion of both parties’ electorate resides in smaller towns and rural areas that face challenges such as depopulation, a shortage of well-paid jobs, and limited access to public services. These voters are also frequently disillusioned with Germany’s elite and the political system.[2]

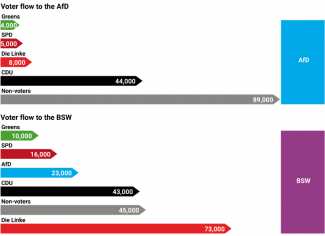

Both parties have effectively drawn voters away from other parties, as well as from one another, albeit less frequently. The AfD has primarily gained ground at the expense of the CDU and Die Linke, while also proving highly effective at mobilising non-voters. The BSW, on its part, has primarily attracted voter support from Die Linke (a substantial number of BSW activists come from that party), as well as from the CDU, the SPD, and even the Greens. Additionally, some voters perceive the BSW as an appealing alternative to the AfD, which they refrain from supporting due to its extreme right-wing stance (this is especially apparent among non-voters and, to a lesser extent, former AfD voters).

Chart. The flow of the electorate to the AfD and the BSW in the Landtag election in Saxony in 2024

Source: the author’s own analysis based on exit polls published by the ARD.

Paradoxically, despite their fundamental ideological differences, the two parties hold the most convergent views on the issues currently dominating German public debate: the state’s policy towards Russia and Ukraine, as well as their approaches to migration and climate issues. Regarding Russia policy, the leaders of the AfD and the BSW echo Russian propaganda, claiming that the invasion of Ukraine is, in fact, a proxy war between Moscow and Washington.[3] They call for an immediate ceasefire, an end to Germany’s support for Kyiv (including assistance to Ukrainian refugees in Germany), and the initiation of talks with the Russian Federation. Additionally, they emphasise that Europe can only achieve security through cooperation with Russia, rather than opposition to it. Consequently, they propose lifting sanctions and normalising relations with Russia.

Anti-Americanism is a shared stance of both the AfD and the BSW. They regard the US as akin to a colonial power, oppressing Germany and seeking to entangle it in various conflicts, including through the presence of US troops and nuclear weapons on German territory.[4] Both the BSW and the AfD demand their withdrawal.[5]

Both parties advocate similar measures to curb migration. They call for a substantial reduction in the number of asylum applications Germany accepts, an acceleration of deportations, and a significant reduction in social welfare benefits. Additional priorities include maintaining border controls, increasing the number of police officers, and strengthening internal security.

The AfD and the BSW also share similar views on climate policy. They criticise Germany’s and the EU’s actions in this area, contending that they excessively interfere in citizens’ lives and consequently harm the German economy. An example of this stance is their opposition to the EU’s decision to ban the registration of new combustion engine cars from 2035. The solutions they propose are largely aligned, including abandoning subsidies for renewable energy technologies and lifting restrictions on fossil fuels. They also call for lowering electricity prices by increasing the supply of electricity (including importing energy from Russia), abolishingCO2 levies, and reducing energy taxes.

A selective approach to history

Both parties exhibit a tendency to relativise history. For the far right, references to Germany’s past are integral to its platform and play a significant role in election campaigns and statements by its leaders. In addition to highlighting the positive aspects of German–Russian cooperation, such as during Otto von Bismarck’s rule, both parties often relativise the policies of Nazi Germany. The most striking example of this strategy is evident in statements by Maximilian Krah, the AfD’s former leading candidate in the European Parliament elections, who claimed that “not every action carried out by the SS can be clearly assessed as a crime”. In the past, Krah repeatedly attempted to downplay Germany’s culpability for crimes committed during the Second World War.[6]

The BSW does not dispute Germany’s responsibility for the outbreak of the Second World War; on the contrary, it firmly distances itself from the AfD’s efforts to minimise history. The BSW’s documents do not contain any historical assessments, including of the GDR era. However, several statements by its representatives on the subject are characterised by a narrative that highlights only the positive aspects of life during that period, while disregarding critical perspectives.[7] This portrayal of the past resonates with the BSW’s oldest voters in the former GDR, who constitute the core of its electorate (see Appendix 2). Wagenknecht herself joined the Socialist Unity Party of Germany (Sozialistische Einheitspartei Deutschlands, SED) in 1989 and defended the GDR’s socio-political system for several years following its collapse.[8] She later renounced these views.

Divergent views

There are numerous differences between the platforms of the AfD and the BSW, the most significant being the extent of state interference in the economy and regulation of citizens’ lives. The AfD and the BSW also hold significantly divergent views on issues such as the Middle East conflict, labour migration to Germany, and the causes of the climate crisis (see Appendix 1).

The AfD emphasises its liberal-conservative background, particularly regarding its economic views. The party advocates cutting social welfare benefits and reducing taxes. It also proposes introducing a programme of compulsory ‘community work’ for the long-term unemployed, requiring 15 hours of paid weekly work for the benefit of local communities. The AfD further suggests reducing the number of individuals eligible for social welfare services, restricting them to German citizens and residence permit holders. Additionally, the party proposes exempting foreign seasonal agricultural workers from the requirement of being paid the minimum wage.[9] The AfD’s approach to the minimum wage has evolved. The party now supports maintaining it as a tool to ensure a minimum standard of living and to shield migrants from the adverse effects of migration. However, it simultaneously opposes raising the minimum wage.

Against this backdrop, the BSW’s demands appear more left-leaning, as they are rooted in the social welfare tradition. Sahra Wagenknecht’s party advocates introducing an inheritance tax, strengthening the role of trade unions, and raising the minimum wage to at least €14 per hour (currently it stands at €12.41). The party also opposes the commercialisation of public services and proposes increasing pensions by abolishing taxes on pensions below €2,000 per month. To protect the German industrial sector, the BSW advocates for the introduction of EU-wide tariffs on imports from countries with unfair labour and environmental standards. Unlike the AfD, it does not oppose Germany’s overarching climate policy, which centres on phasing out fossil fuels. However, it contends that the associated costs are excessive.

Beyond economic matters, the list of divergences extends to other key issues. The two parties are unlikely to align on the Middle East conflict, which holds particular significance in German politics due to the country’s responsibility for Holocaust crimes and its sizeable Muslim community of approximately five million individuals.[10] The AfD strongly supports Israel and opposes, among other measures, the embargo on arms exports to the country. It unequivocally condemns anti-Israeli rhetoric in Germany, particularly when expressed by individuals of Arab origin. Similarly to the federal government, it supports a two-state solution, envisioning the establishment of both an Israeli and a Palestinian state. The BSW, by contrast, strongly criticises Israel’s actions against the civilian population (in Gaza and Lebanon) and calls for a ban on arms sales to Israel.

Cooperation prospects

The analysis presented above indicates that, despite significant platform and ideological differences, cooperation between the AfD and the BSW is possible. Although it could be most successful in foreign policy issues, implementing both parties’ proposals in this area seems improbable in the medium term as they are unlikely to co-form a federal government.

Effective cooperation between the two extremes is possible on issues such as climate policy and efforts to curb migration to Germany. This is because these areas fall within the competence of individual federal states, where the BSW and the AfD are far more likely to assume power.

Despite this, Sahra Wagenknecht’s party has so far ruled out a formal coalition with the AfD, primarily due to her reservations about certain individuals, particularly several AfD politicians under surveillance by Germany’s counterintelligence. The BSW’s harshest criticism is directed at Björn Höcke, the AfD leader in Thuringia. In the Landtag election in this federal state, the two parties secured a combined 48.6% of the vote (47 out of 88 seats) giving them a majority capable of governing the state. Meanwhile, in all three eastern federal states that held their Landtag elections in September, both parties have expressed their willingness to cooperate on an ad hoc basis on specific issues, such as migration policy, pressurising the federal government to reduce support to Kyiv, holding politicians accountable for their actions during the COVID-19 pandemic, state media reform, limiting climate policy measures, and education reform.

Possible obstacles to achieving common goals include the ambitions of party leaders and internal disputes. This is particularly true of the BSW, a relatively young party centred around a strong leader, which has not yet encountered platform-related or personnel disputes. An example of this is the conflict over the decision by the party representatives in Thuringia, who, according to Wagenknecht, acted too hastily in forming a coalition with the CDU and SPD without ensuring that the BSW’s demands concerning policy towards Russia were sufficiently addressed. The party’s pragmatic wing, led by Katja Wolf, head of the regional party organisation in Thuringia, seeks to co-form a government and collaborate with other parties.[11] Meanwhile, Wagenknecht’s primary focus is achieving the best possible result in the 2025 Bundestag election, rather than having her party participate in regional coalitions. It cannot be ruled out that she might disrupt scenarios involving the BSW co-forming governments in individual federal states with the AfD. Firstly, if the BSW co-forms such a government, its voters would have to accept that its party leader’s unrealistic demands concerning the federal state’s influence on Germany’s foreign policy are unattainable. Secondly, engaging in realpolitik could ‘wear out’ the party and jeopardise its popularity.

With the Bundestag election less than a year away, the AfD’s national support stands at less than 19%, while the BSW’s is at 9%. Currently, it seems unlikely that these two parties could form a coalition or cooperate successfully in the Bundestag. However, the prospect of cooperation between the AfD and the BSW on issues requiring a two-thirds majority will be a key focus in next year’s elections. These issues include constitutional amendments and specific foreign policy decisions, such as transferring certain competences to supranational organisations and ratifying selected international agreements, which both parties could block.

By pressurising mainstream parties to adopt tougher political agendas, the AfD and the BSW are reorienting German politics, as evident in the shifting approach to migration. This pressure is set to intensify further ahead of the Bundestag elections. Moreover, in a scenario where only five parties are elected to parliament, forming a federal government would require votes from three of them: the Christian Democrats, the SPD, and the Greens. In such a scenario, the AfD and the BSW would remain in opposition, potentially making it difficult for the new government to secure broad public support for controversial decisions, particularly on foreign policy, for example regarding aid to Ukraine, as well as migration and climate issues. For the opposition, this would present an opportunity to capitalise on public discontent and consolidate their position, potentially leading to enhanced cooperation between the extreme parties.

APPENDIX 1

Selected elements of political platforms of the AfD and the BSW

APPENDIX 2

Selected features of the BSW’s and the AfD’s electorate

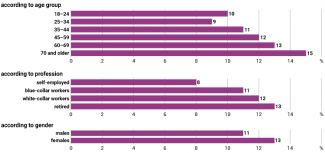

Chart 1. The structure of BSW voters in Saxony according to age group, profession, and gender

Source: the author’s own analysis based on exit polls published by the ARD.

Chart 2. The age structure of the AfD’s electorate in Saxony (change compared to 2019)

Source: the author’s own analysis based on exit polls published by the ARD.

[1] K. Frymark, ‘Success for the AfD and the BSW in Thuringia and Saxony’, OSW, 2 September 2024; idem, ‘Success for the SPD in Brandenburg’, OSW, 23 September 2024, osw.waw.pl.

[2] See ‘Sachsen Landtagswahl 2024’, Tagesschau, 1 September 2024; ‘Thüringen Landtagswahl 2024’, Tagesschau, 1 September 2024; ‘Brandenburg Landtagswahl 2024’, Tagesschau, 22 September 2024, tagesschau.de.

[3] J. Bender, F. Schmidt, ‘Wie AfD und BSW russische Propaganda verbreiten’, Frankfurter Allgemeine, 21 October 2024, faz.net.

[4] Publications by the Compact magazine, which is under surveillance by Germany’s counterintelligence, exemplify the radical anti-Americanism of groups associated with the AfD. See, for example, ‘Ami go home! Wie uns NSA, CIA und Army besetzen’, Compact, compact-shop.de.

[5] L. Gibadło, J. Gotkowska, ‘The BSW campaign against US intermediate missile systems and a NATO HQ in Germany’, OSW, 25 October 2024, osw.waw.pl.

[6] See S. Gaschke, ‘«Unsere Vorfahren waren keine Verbrecher»: Der AfD-Spitzenkandidat Krah will die Christlichdemokraten «zerstören» – auch mithilfe türkischstämmiger Wähler’, Neue Zürcher Zeitung, 7 September 2023, nzz.ch.

[7] See an interview with Katja Wolf: ‘“Wir wollen eine Zumutung sein“’, Zeit Online, 19 October 2024, zeit.de.

[8] A. Kohnen, J. Gaugele, ‘„Ich wende den Begriff Unrechtsstaat auf die DDR nicht an“’, Berliner Morgenpost, 20 January 2017, morgenpost.de.

[9] For the AfD’s motion see ‘Unsere Bauern retten – Ausnahmeregelung beim gesetzlichen Mindestlohn für ausländische Erntehelfer bei heimischem Obst-, Gemüse-, Wein- und Hopfenanbau einführen’, Drucksache 20/11940, Deutscher Bundestag, 25 June 2024, dserver.bundestag.de.

[10] ‘Muslimisches Leben in Deutschland 2020’, Bundesamt für Migration und Flüchtlinge, 28 April 2021, bamf.de.

[11] M. Wehner, ‘Wagenknecht gegen Wolf’, Frankfurter Allgemeine, 21 October 2024, faz.net.