Lithuania is losing people without a fight

Lithuania ranks among the world’s top ten fastest-depopulating countries.[1] Throughout over three decades of independence, its population has dramatically decreased by over 800,000 people. The current population stands at just 2.8 million, with over 20% of residents being above retirement age. The main reasons behind Lithuania’s depopulation and ageing society are ongoing emigration to the West and a declining birth rate. In recent years, approximately 22,000 children have been born annually, while around 40,000 people die each year – a rate insufficient to ensure generational replacement. Long-term projections indicate that depopulation is likely to continue.

Although Lithuania’s government elites recognise depopulation as a serious threat, no policy focused on counteracting these negative trends has been implemented so far. Families report a lack of financial incentives, quality education for children, medical care, and family-oriented housing policies. Efforts to curb emigration have proven ineffective, partly due to insufficient support provided to returnees. A potential opportunity to reverse these demographic trends lies in welcoming labour migrants from outside the EU. Since 2020, the number of Ukrainians, Belarusians, and migrants from Central Asia settling in Lithuania has increased. However, implementing an effective integration policy to retain these foreign nationals in a way that benefits the country’s economy and society remains a challenge.

The depopulation trend

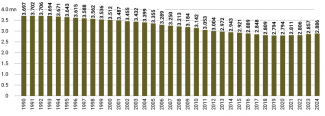

When Lithuania regained independence in 1991, its population stood at 3.706 million. Since then, this figure has steadily declined, stabilising at 2.794 million in 2019, before beginning a modest increase due to positive net migration.

As of 1 January 2024, the country’s population was 2.885 million. This represents a loss of 821,000 people over three decades, equivalent to the combined populations of Lithuania’s two largest cities, Vilnius and Kaunas. Alongside this decline, population density decreased from 59 people per square kilometre in 1990 to 46 in 2024. Lithuanians predominantly reside in urban areas, with the urban population percentage remaining largely unchanged at 68.5% today (compared to 68% in 1990).[2]

Chart 1. The population of Lithuania from 1990 to 2024

Source: Official Statistics Portal.

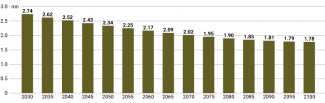

Chart 2. Projected population of Lithuania by 2100

Source: Eurostat.

The depopulation also affects ethnic minorities

Since 1990, the ethnic composition of Lithuania’s population has changed slightly, and its society remains relatively homogeneous. According to the latest census conducted in 2021, ethnic Lithuanians constituted 84.6% (2,378,100) of the population. The largest minority group was ethnic Poles, numbering 183,400 (6.53%). Other groups included Russians (141,200; 5%), Belarusians (28,100; 1%), and Ukrainians (14,200; 0.5%).[3] Considering the recent growth of the last two groups, this composition shifted by early 2024, with ethnic Lithuanians making up 82.6%, Poles 6.3%, Russians 5%, Belarusians 2.1%, and Ukrainians 1.7% of the population.[4]

The Polish minority resides predominantly in the southeastern part of Lithuania (the Vilnius district), where 93.18% of all ethnic Poles in the country are concentrated. In the capital district, which includes Vilnius and its surrounding areas, Poles account for 21.08% of the population. The majority of Poles in Lithuania (170,900 individuals; representing 46.57% of the total Polish population) reside in Vilnius, where they account for 15.35% of the city’s residents. Large Polish communities also exist in the Vilnius, Šalčininkai, Švenčionys, and Trakai districts, with Poles forming the largest ethnic group in the first two: 76.31% (22,900) in Šalčininkai and 46.75% (45,000) in the Vilnius district.[5]

The Polish minority has experienced depopulation proportionate to Lithuania’s overall population decline. In 2001, ethnic Poles consisted 6.74% of the population, decreasing to 6.58% in 2011. Between 2011 and 2021, their proportion dropped by 0.1 percentage points, while the Russian minority saw a sharper decline of 0.8 percentage points, from 5.8% to 5%.[6]

Depopulation vs. emigration

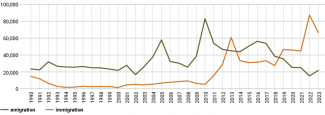

Over the past three decades, emigration has impacted every municipality in Lithuania, with none spared from the effects of depopulation. According to official statistics, approximately 1.166 million citizens emigrated from the country between 1990 and 2023, while over 670,000 people settled there. This resulted in a negative net migration of 496,000 people.

Chart 3. Emigration and immigration in Lithuania from 1990 to 2023

Source: Official Statistics Portal.

Lithuanians started leaving their country immediately after the collapse of the USSR, when borders to the West opened, and Lithuania underwent an economic transformation. This led to the closure of many industrial plants, collective farms, and municipal enterprises. At that time, approximately one-third of the country’s population worked in agriculture.[7] Annually, 20,000–30,000 young citizens, primarily aged 25–35, left the country. The first major wave of emigration from Lithuania occurred after the country’s accession to the EU in 2004. This was followed by another wave during the European economic crisis four years later, when annual emigration surged from approximately 40,000–50,000 to nearly 90,000. The most popular destinations included the United Kingdom, Germany, Norway, Ireland, the United States, and Spain. Emigration to the West slowed due to Brexit and the COVID-19 pandemic, but approximately 15,000–20,000 Lithuanians continue to leave annually.

Accurate data on Lithuanians currently living abroad is difficult to obtain, as not all permanent relocations have been registered. Only recently have Lithuanian diplomatic missions been tasked with gathering diaspora information based on population censuses in the countries where they operate. The emigrants were predominantly young, working-age individuals, seeking better opportunities abroad. Official statistics also exclude those born abroad, representing the second or even third generations of emigrants. While Lithuanian data suggests that the country’s population has been reduced by approximately15% due to emigration since 1990, accounting for the descendants of emigrants not included in the statistics could increase this figure to 25%. According to Dalia Henke, Chair of the Lithuanian World Community, the number of emigrants’ children born abroad may exceed 300,000.[8]

The government lacks any comprehensive analyses that would explain why the outflow of Lithuanians from their country continues. Living standards in Lithuania are converging with those in other EU countries. Average wages are rising twice as fast as the EU average, GDP per capita based on purchasing power parity (PPP) reaches 87% of the EU average, and the unemployment rate stands at 6.2% – slightly below the EU average. However, factors such as a housing shortage, a complex tax system stifling entrepreneurship, lower healthcare and education standards, and limited access to childcare facilities for working parents may influence decisions to emigrate. Additionally, the international situation, particularly the war in Ukraine, not only discourages reemigration to Lithuania but also prompts further emigration.

The problems returnees are facing

Returning Lithuanians face numerous challenges. The primary issue is securing employment that matches their qualifications. Employers are often reluctant to hire them, fearing high salary expectations and the risk of them departing once more. Housing is another significant obstacle, as renting or obtaining a mortgage is nearly impossible without a formal employment contract. Furthermore, securing places in kindergartens or integrating older children into the education system presents additional difficulties.

Returning migrants also criticise the red tape associated with moving back to Lithuania, including obtaining documents and local certifications.[9] Lithuanians living abroad are further disheartened by the constitutional ban on dual citizenship. Over the past five years, Lithuania has removed more than 5,000 individuals from its citizen registry for acquiring citizenship in another country.

The ageing society

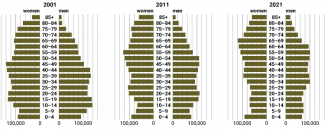

The emigration of young people has significantly altered Lithuania’s population structure, leading to a disproportionate increase in the elderly population. The median age in Lithuania has risen to 44 years – 40 for men and 47 for women – an increase of two years since 2013. In comparison, the EU median age is 44.5 years,[10] indicating that Lithuania is nearing inclusion among the fastest-ageing countries.

Table. Structure of the Lithuanian population in 2023 by age groups

Source: The population of Lithuania (edition 2023), Official Statistics Portal, osp.stat.gov.lt.

Chart 4. The age pyramids of the Lithuanian population over the past 20 years

Source: data from the Official Statistics Portal.

Emigration has also reduced Lithuania’s population growth potential. The most notable demographic shift reflecting the ageing of Lithuania’s population over the past decade has been a 27.9% decline in the number of individuals aged 15–29. This is a critical loss, as this age group represents potential future parents. The ageing process is further highlighted by the increase in the 60–69 age group, which grew by 26.8%, and those aged over 85, whose numbers rose by 29.3%.

These demographic shifts have been accompanied by rising mortality rates. Following a peak in 2021, driven by the COVID-19 pandemic, when the death rate reached 17 per 1,000 inhabitants, the figure fell to 15.1 per 1,000 in 2022. Meanwhile, life expectancy has increased from 72 years in 2013 to 77.3 years a decade later. However, this remains relatively low compared to the EU average of 81.5 years. A significant disparity between male and female life expectancy persists, with women outliving men by a full decade.

The ageing population is also impacting the labour market. Lithuania has 1.43 million economically active individuals and 912,000 inactive residents, including 547,500 pensioners. The age group nearing retirement (60–64 years) currently totals 220,800, while the cohort soon entering the labour market (15–19 years) is markedly smaller at 136,600. Consequently, due to generational shifts alone, the working-age population is projected to shrink by 70,000–80,000 in the coming years. Additionally, the average working age has risen, from 40 years in 1998 to nearly 45 today. At present, there are just over three working-age individuals per pensioner, a ratio expected to decline to two by 2050 under current demographic trends.

The low birth rate

The second most significant factor negatively affecting Lithuania’s population, after emigration, is the persistently low birth rate. Achieving the number of births necessary for generational replacement remains unfeasible in the short term. In 2022, Lithuanian women of reproductive age gave birth to an average of 1.27 children, compared to the EU average of 1.46. The fertility rate has shown minimal improvement over the past two decades and remains near its lowest recorded levels of 1.23 and 1.26 in 2002 and 2003, respectively. Since 2015, the number of children born in Lithuania has declined annually, reaching historically low levels. Furthermore, the number of women of reproductive age has also decreased significantly – from 924,000 in 1990 to just 589,000 in 2022.

Chart 5. Births in Lithuania from 2015 to 2023

Source: the author’s own estimates based on data from the Official Statistics Portal.

The declining birth rate in Lithuania is influenced by several economic factors. Raising a child costs between €3,000 and €5,000 annually,[11] while the average net monthly salary is €1,249. Housing availability is decreasing, with property prices rising by 40% over the past four years, and mortgage interest rates becoming unaffordable even for the middle class. Parents are questioning the quality of public education, opting for more expensive private schools, and this further increases child-rearing costs. Additionally, approximately25% of parents are single, and the average age of women having their first child has risen to 30.2 years. Experts highlight non-economic factors affecting birth rates, including the growing trend of voluntary childlessness and weakening emotional connections among young people, leading to fewer families being established.[12] Suicide remains a significant issue across age groups. Despite a halving in suicide rates over the past decade – from 36.6 per 100,000 people in 2013 to 19.6 in 2023 – Lithuania continues to have the EU’s second-highest rate, surpassed only by Slovenia.

To support families, Lithuania implemented child benefit payments in 2018, inspired by Poland’s system. Each child under 18 (or 23 if still in education) is entitled to a monthly allowance of €96.25. Families with three or more children receive an additional monthly payment of €56.65 per child, bringing the total to €152.90 per child. This additional benefit is also available for children with disabilities and those from low-income families (with a monthly income below €264 per person). Children from lower-income families are eligible for free school lunches, €110 for school supplies, and meals at summer camps. Additionally, preschoolers and first- and second-grade pupils receive meals. A one-time payment of €605 is granted for each child born in Lithuania, with additional support provided for twins and multiple births.[13] The state also offers flexible parental leave options (following maternity leave) allowing parents to take leave until their child reaches the age of three.

If not children, then immigrants

Currently, 221,000 foreigners reside in Lithuania, including 116,000 on temporary residence permits for employment. If current immigration trends persist, their number is expected to grow to approximately 500,000 within five years. The largest diaspora is Ukrainian, numbering just over 76,000, of whom 44,000 are war refugees. Belarusians form the second-largest group, with over 62,500 residents. The number of Russian citizens, the third-largest foreign group, is declining slightly and now stands at 15,500. Uzbeks make up the fourth-largest diaspora, with a growing population of 10,200, followed by Tajiks at 7,000. Other significant groups include Kyrgyz, Azerbaijanis, and Indians. Among Central Asian migrants, 90% are men.

Legal immigrants increasingly choose to stay longer in Lithuania, with proof of this being the growing number of temporary (including renewed) and permanent residence permits issued. In the first half of 2024, 78,000 temporary residence permits were granted, including over 33,000 first-time permits and 44,000 renewals.[14] By contrast, during the same period in 2023, nearly 72,000 first-time permits were issued, yet only 14,500 were renewed. In the second half of 2023, 51,000 foreigners obtained their first temporary residence permits, while just over 15,000 renewed theirs. Additionally, 2,455 individuals received permanent residence permits in the first half of 2024, compared to 1,770 for the entire previous year. Despite these trends, the total number of foreigners living in Lithuania has remained nearly unchanged over the past six months compared to the previous year.

Fifty per cent of foreigners choose to settle in Lithuania for employment opportunities, while others, particularly Ukrainians and Belarusians, seek refuge from war or repression under Alyaksandr Lukashenka's regime. Nevertheless, many of these migrants also integrate into the Lithuanian labour market, which has a high demand for workers.

Prior to 2020, Lithuania focused less on immigration strategies and integration efforts, concentrating instead on the emigration of its own citizens. The government is currently addressing this gap, aiming to balance employers’ demands for foreign labour. A key challenge lies in balancing employers’ demands for state approval to bring in foreign workers with national security policies, which also encompass the protection of the Lithuanian language. This is particularly significant given that Lithuania bases its migration strategy on integration through language.[15]

On 20 June 2024, the Seimas (Lithuania’s unicameral parliament) introduced stricter conditions for recruiting labour migrants from non-EU countries under the Law on the Legal Status Aliens. Priority is given to skilled workers (currently numbering just 6,000 in Lithuania) with residence permits. Employment on the basis of visa-free travel or Schengen visas has been prohibited, except for select groups such as lecturers, researchers, and citizens of economically developed countries.

Lithuania has introduced a mechanism to calculate the maximum annual quota for foreign workers. The number of labour migrants allowed in any calendar year must not exceed 1.4% of the country’s population, based on data from the State Data Agency published on 1 July. Oversight of foreign workers and the businesses employing them has also been tightened. Employers are required to hold licences authorising the specific activities necessitating foreign workers and risk licence revocation if they fail to register an employee or provide false information. Currently, 42 companies in Lithuania have been implicated in such violations. Employers must hire foreign workers for full-time positions and collect details on their qualifications and work experience. Compliance is monitored by the Migration Department under the Ministry of the Interior, in coordination with the police, State Border Guard Service, Labour Inspectorate, and Tax Inspectorate.

Private business representatives primarily advocate for admitting less skilled workers, who are employed in construction, transport, industrial production, and low-skilled services such as courier jobs. The labour market has swiftly integrated migrants from Ukraine, who are regarded as adapting well to society, notably through learning Lithuanian. The faster an immigrant learns Lithuanian, the higher their chances of successfully bringing their family to the country. Language proficiency is becoming one of the most critical criteria in the context of recent legislative changes regarding the extension of work-related residence permits for migrants.

Despite efforts to regulate migration, Lithuania remains divided both socially and politically on the issue of increasing migration. Two opposing perspectives prevail: on one hand, liberal groups, often supported by business organisations, contend that increased labour migration is inevitable. On the other hand, critics argue that migration will not resolve demographic challenges and advocate for prioritising policies to boost fertility rates and encourage repatriation. A key argument in favour of labour migration is the significant revenue it generates for the state. In 2023, foreign workers contributed €2.8 billion to the economy, up from €1.34 billion in 2021 and €2 billion in 2022. However, concerns remain that excessive regulation could drive migrants to relocate to countries with more liberal policies.

Lithuania is losing the struggle with depopulation

Lithuanian authorities rely exclusively on international agencies, such as Eurostat and the UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs, for long-term population forecasts, which predict continuous declines until the end of the 21st century. According to Eurostat, Lithuania’s population will decrease to 2.7 million by 2030, 2.4 million by 2045, 2.3 million by 2050, and just 2 million by 2070.

The UN’s forecast is even more pessimistic, projecting a population of 2.3 million by 2045 and 2.2 million by 2050, with only 1.3 million people of working age (down from 1.8 million today). Births are expected to fall to 21,000 annually by 2050 and just 12,000 by 2100.

These deteriorating demographic indicators underscore the failure of successive governments to implement effective measures to combat depopulation. Demographic issues have been neither a political priority nor a focal point in electoral campaigns. During the tenure of Prime Minister Saulius Skverneli’s centre-left government, an initiative was undertaken to launch a demographic improvement programme. The Long-Term Family Strengthening Programme for 2020–2028 was adopted as Lithuania’s first strategic family policy document. It aimed to cultivate positive societal attitudes towards families and promote equal opportunities for parents and those without children. However, the programme was shelved when the right-wing government took office at the end of 2020. Conservatives and liberals prioritised promoting gender equality and encouraging women to re-enter the workforce after childbirth, including through reforms to parental leave policies.

At the end of its four-year term, on 15 June 2024, the right-wing government adopted a resolution titled ‘On the Future of Lithuanian Demographic Policy.’ The resolution acknowledged depopulation as a strategic, long-term issue and proposed creating an agency to develop programmes addressing this challenge. The suggested measures included policies to boost fertility, promote healthy lifestyles, encourage return migration, and integrate immigrants. However, these initiatives are unlikely to be realised, as the centre-left regained power in the late 2024 parliamentary elections. The new coalition’s agenda includes only general pledges to offer additional family benefits, housing assistance, more preschool places, and improvements in the education system. With Lithuania’s main political forces alternating in power every four years and failing to build on their predecessors’ demographic initiatives, achieving unified and sustained engagement in addressing the demographic crisis remains a significant challenge.

Experts emphasise the need for authorities to conduct comprehensive research on society and migration while implementing a long-term family policy. Many argue that financial benefits alone are insufficient and cannot replace such a policy. Some specialists advocate for abandoning efforts to increase population numbers and instead focus on creating a family-friendly environment, including improving healthcare and education quality.

[1] Based on the annual world population report published by the US Central Intelligence Agency – CIA Population growth rate 2024, cia.gov.

[2] Based on preliminary estimates for 2024, osp.stat.gov.lt.

[3] 2021 Population and Housing Census, Official Statistics Portal, osp.stat.gov.lt.

[4] No absolute numbers were provided. Proportion of the population by ethnicity, compared to the total resident population, Official Statistics Portal, osp.stat.gov.lt.

[5] From the total population count. These figures are based on the 2021 census (osp.stat.gov.lt).

[6] I. Blažienė et al., Lietuvos gyventojų demografinių struktūrų ir procesų kaita, Institute of Sociology at the Lithuanian Centre for Social Sciences, Institute of Sociology, Vilnius 2023, lstc.lt.

[7] The exact number of enterprises that collapsed during Lithuania’s post-Soviet economic transformation is unknown. Some were privatised, often under unclear procedures referred to as ‘privatisation’, while others went bankrupt. Land previously owned by collective farms began to be reclaimed by former owners or their descendants, many of whom are now city residents.

[8] A. Marcinkevičius, ‘Amžinas klausimas: kiek pasaulyje gyvena lietuvių ir kokia valstybė norime būti – uždara ar atvira pasauliui?’, Delfi, 22 January 2021, delfi.lt.

[9] ‘Kodėl emigrantai (ne)grįžta? Finansai, mentaliteto skirtumai ir biurokratiniai iššūkiai’, 15min, 10 December 2021, 15min.lt.

[10] Data as of 1 January 2023.

[11] S. Strockytė-Varnė, ‘Vaiką užauginti kainuoja. Kaip teisingai pasirinkti, kam išleisti pinigus?’, SEB, 29 September 2022, seb.lt.

[12] M. Matulevičius, ‘Gimdome 3 kartus mažiau nei nepriklausomybės pradžioje, kodėl to nebedarome?’, LRT, 14 April 2024, lrt.lt. The author references findings from studies conducted by various Lithuanian researchers specialising in social issues, including family-related challenges.

[13] The data originates from the Ministry of Social Protection and Labour (socmin.lrv.lt).

[14] ‘Foreigners arriving in Lithuania stay in the country longer’, Migration Department under the Ministry of the Interior of the Republic of Lithuania, 18 July 2024, migracija.lrv.lt.

[15] On 3 October 2024, the Seimas of the Republic of Lithuania ruled that, beginning in 2026, foreign workers in Lithuania must demonstrate sufficient proficiency in Lithuanian to serve customers. Employers will be responsible for ensuring compliance with this requirement.