The debt brake: Germany in a crisis of uncertainty

The debt brake (Schuldenbremse) is a German constitutional rule introduced during the global financial crisis in 2009 to ensure the country’s financial stability. Under this mechanism, the annual federal deficit cannot exceed 0.35% of GDP, while federal states are entirely prohibited from taking on new net debt. The COVID-19 pandemic, the war in Ukraine, and prolonged economic stagnation have reignited debates over its effectiveness. Differing views on the matter have even contributed to the collapse of the ruling coalition.

The debt brake, along with other financial and economic matters, has become a central topic in the campaign ahead of the snap election to the Bundestag. The SPD, the Greens, and the BSW advocate loosening the debt brake, increasing investment spending, and maintaining current social welfare benefits. In contrast, the CDU/CSU, FDP, and the AfD support reducing or eliminating certain benefits while preserving existing fiscal rules. The most likely government configuration following the election appears to be a CDU/CSU coalition with either the SPD or the Greens, meaning that the constitutional debt limit is expected to remain a key issue in negotiations for the next legislative term.

The genesis of the debt brake

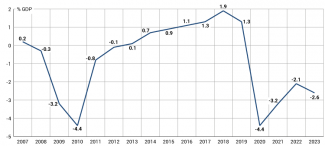

The debt brake (Schuldenbremse) is a fiscal rule that replaced the so-called golden fiscal rule,[1] enshrined in Article 115 of Germany’s Basic Law. It was introduced in response to the 2008–09 financial crisis.[2] At that time, the German government incurred high costs for rescue programmes amounting to approximately €464 billion, causing public debt to rise to approximately 81% of GDP in 2010. To reduce the risk of further debt accumulation and violations of EU fiscal rules,[3] a new fiscal framework was established. The debt brake restricted the ability to take on new debt: since 2016, the structural deficit at the federal level must not exceed 0.35% of GDP, and since 2020, federal states have been completely prohibited from incurring new net debt. This is a highly restrictive requirement compared with EU rules, which limit the budget deficit of member states to 3% of GDP. The debt brake is considered in long-term fiscal policy decisions rather than temporary economic fluctuations, which is why it was suspended in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic[4] (see Chart 1). As a constitutional measure, any reform or repeal of the debt brake requires a two-thirds majority in both the Bundestag and the Bundesrat.

The introduction of the debt brake has its roots in German history. The consequences of hyperinflation in the 1920s, the Great Depression of 1929, and the experience of state interventionism during Nazi Germany laid the foundation for the emergence of an economic school of thought known as ordoliberalism. According to ordoliberals, the free market is the foundation of the economy, and the state’s role should be limited to establishing legal and regulatory frameworks rather than directly intervening in market processes.

In the face of post-war debt to the Allied nations, which hindered the achievement of stable public finances, and the neoliberal shift of the 1980s,[5] ordoliberal principles became deeply embedded in the mindset of many German politicians. One of the consequences of this strong commitment to fiscal stability was the so-called black zero (Schwarze Null) strategy, implemented by Christian Democratic finance minister Wolfgang Schäuble between 2009 and 2017. This policy aimed to maintain a balanced budget, ensuring that expenditures did not exceed revenues, thereby preventing an increase in public debt.

Chart 1. Germany’s budgetary surplus and deficit

Source: ‘Germany Government budget deficit’, countryeconomy.com.

Strengths and weaknesses of the debt brake

Supporters of the debt brake argue that it prevents the so-called snowball effect, whereby public debt can grow independently if the interest payments on accumulated debt exceed the nominal rate of economic growth in a given year. Thus, the debt brake ensures the long-term stability of public finances. Another frequently cited argument in public discourse is intergenerational fairness. Debt is seen as a burden on future generations, who will be responsible for repaying the interest.

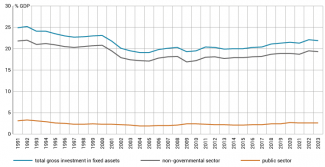

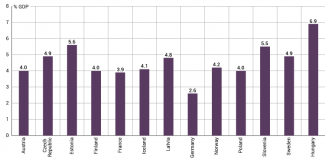

Economists are increasingly challenging the belief that debt is inherently harmful. Borrowing can lead to negative consequences if the economy is already operating at full capacity and new debt-financed expenditures are directed primarily towards current consumption rather than investment. The main criticism of the debt brake is that it may hinder essential public investment. In Germany, public investment has remained at a stable level of around 2–3% of GDP in recent years (see Chart 2), which is relatively low compared to other countries in the region (see Chart 3). Moreover, this level of investment is not sufficiently aligned with the changing needs of German society and the deteriorating quality of infrastructure.

Chart 2. Share of new investments in Germany

Source: ‘Investitionen’, Federal Statistical Office of Germany, destatis.de.

According to calculations by the Bertelsmann Foundation, Germany should allocate over €100 billion annually to public investment to compensate for many years of underfunding.[6] Media reports indicate that 10,000 bridges across the country require modernisation, while Deutsche Bahn has identified investment needs totalling €45 billion.[7] It is estimated that in 2024 every third train in Germany was delayed.[8] Additionally, there is a shortage of approximately 800,000 homes nationwide.[9] Germany has also set a target of achieving climate neutrality by 2045, which will require substantial investments in technology, infrastructure, and support for energy-intensive industries undergoing decarbonisation. To address climate challenges, annual expenditures of €40–50 billion may be necessary.

The off-budget special fund of €100 billion, established in 2022 to finance the Bundeswehr and meet NATO’s requirement of spending 2% of GDP on defence, is expected to be exhausted by 2027. To continue fulfilling allied commitments in the subsequent years, Germany will require additional defence spending estimated at €30 billion annually. Beyond defence, Germany also faces significant investment needs in education, research and development, digitisation, and rising pension expenditures. These financial demands are disproportionately high relative to the €488 billion budget planned by the SPD–Greens–FDP coalition for 2025.

Chart 3. The value of public investment in selected countries in 2022

Source: ‘Government at a Glance 2023’, OECD, 30 June 2023, oecd.org.

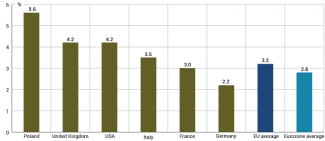

Germany can rely on relatively low-cost debt, meaning there is no immediate risk of the snowball effect mentioned earlier. Long-term German government bonds are issued at relatively low interest rates (see Chart 4). The country enjoys a high level of financial stability and strong creditor confidence, which helps it avoid excessive debt servicing costs.

Chart 4. Ten-year government bond yield in October 2024 for selected countries

Source: ‘Long term government bond yields’, Eurostat, ec.europa.eu; ‘US 10 year Treasury’, Financial Times, markets.ft.com.

Challenges to the German economy

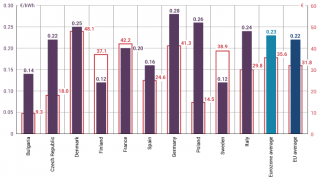

One of the biggest challenges the German government is currently facing involves prolonged economic stagnation and the threat of deindustrialisation. For the second consecutive year, the German economy has been in recession, with GDP declining by 0.2% in 2024 compared to the previous year. The main reasons for this downturn are structural issues that are reducing the competitiveness of domestic businesses. Operating in Germany is becoming increasingly unprofitable due to high energy and labour costs (see Chart 5). This not only discourages foreign investment but also prompts domestic companies to relocate abroad.[10] Additionally, the number of insolvent businesses has been rising for several months,[11] largely due to challenges faced by key industries, particularly the automotive and machine building sectors.

Uncertainty surrounding the snap parliamentary election and the economic policies of the next government is deterring further investment. Excessive bureaucracy and reporting requirements are also cited as major obstacles, with employees spending up to 22% of their working time on administrative tasks.[12] Due to these unfavourable conditions, Germany is not progressing quickly enough to keep pace with competitors in innovation and digitisation. In 2024, Germany ranked 24th in the IMD Competitiveness Index, whereas just ten years earlier, it had been placed sixth. The lack of stability is also reflected in households. The savings rate reached 11.6% in 2024, an increase of 1.2 percentage points relative to 2023.

Chart 5. Labour costs in 2023 and electricity prices in H1 2024 in selected countries

Source: ‘Hourly labour costs’, ‘Electricity prices for non-household consumers’, Eurostat, ec.europa.eu.

Unfavourable external factors include growing competition from the United States and China in the development of green technologies and in the automotive industry. In 2022, President Joe Biden allocated $369 billion in subsidies and tax incentives to support the renewable energy and electric vehicle sectors under the Inflation Reduction Act.[13] Meanwhile, heavily subsidised Chinese electric cars are gaining popularity not only in China but also abroad. In 2024, the export growth rate of passenger cars from Chinese brands was expected to reach 29% relative to the previous year.[14] China is also a key market for German businesses; therefore, economic stagnation in China has significantly reduced domestic demand for imported goods from Germany over the past year. Additionally, Donald Trump’s threats to impose tariffs on EU products presents a further risk to Germany’s status as one of the world’s leading exporters.

Polarisation over the debt brake

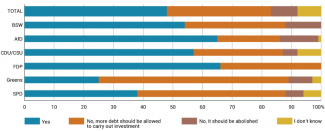

Opinions on maintaining the debt brake vary across the German political spectrum. The liberal FDP is its strongest supporter, given its strict commitment to reducing public debt. A similar stance is held by the CDU/CSU and the AfD, which, like the liberals, would prefer to redirect funds from social welfare policies, such as the citizen’s allowance,[15] towards investment rather than pursuing fiscal expansion. On the other hand, the SPD, the Greens, and the BSW advocate reforming the debt brake to ease its restrictions. They seek to maintain an extensive social welfare policy, facilitate budget-funded subsidies, and increase investment in key sectors. This divide is also reflected in voter preferences (see Chart 6). Supporters of maintaining the debt brake are primarily FDP voters (66% of respondents), as well as the supporters of the AfD (65%), and the CDU/CSU (57%), while those in favour of reform are mostly Greens (72%) and SPD (56%) supporters.

Chart 6. Should the debt brake be maintained in its present form?

Source: L. Wolf-Doettinchem, ‘Schuldenbremse lockern? Immer mehr Deutsche sind dafür’, Stern, 3 December 2024, stern.de.

Political friction and coalition break-up

Conflicting approaches to addressing economic challenges led to political tensions throughout the term of the SPD, Greens, and FDP coalition. Between 2020 and 2022, the debt brake was suspended due to the COVID-19 pandemic and the war in Ukraine, allowing for relatively conflict-free budget management. The instrument was reinstated at the beginning of 2023 (although it was later suspended again retroactively at the end of the year), aligning with Finance Minister Christian Lindner’s (FDP) plans to reduce spending and stabilise public finances. However, reactivating the debt brake clashed with the priorities of the SPD and the Greens, as it restricted their ability to implement key policy proposals.

The reform of the debt brake proved impossible due to opposition from the FDP. As a result, the value of special funds rose sharply (Sondervermögen, SV).[16] Although the original regulations required SV to be included in debt brake calculations, accounting rules for federal budget balances and special funds were amended in 2021 to circumvent these restrictions. The SPD and the Greens made extensive use of this mechanism to avoid conflicts over spending with their coalition partner, the FDP. In 2023, allocations to special funds accounted for 35.9% (€170.9 billion) of budget expenditures, an increase of approximately 26 percentage points compared to 2022.

The most controversial misuse of this practice involved an attempt to reallocate unspent funds from the pandemic relief fund to other purposes. €60 billion in unused funds borrowed in 2021 were transferred to the Climate and Transformation Fund (KTF). However, this manoeuvre was challenged in the Constitutional Court, which ruled against it. As a result, the government was forced to withdraw these funds from the KTF in November 2023, triggering a severe budgetary and political crisis.[17]

The increasing reliance on special funds was politically problematic for Lindner, as advocating additional expenditures risked undermining his credibility as a proponent of fiscal discipline. To counter this, the draft budget for the following year (presented in July 2023) significantly reduced spending in order to reinstate the debt brake. As a result, the budgets of ministries led by the SPD and the Greens were severely cut. For example, the Ministry for Family Affairs (Greens) was allocated only €2 billion out of the €12 billion initially proposed, while the Ministry of Health (SPD) received €16.2 billion, a third less than the previous year.

The conflict reached its peak in the summer of 2024 during negotiations for the 2025 budget. The finance minister attempted to conceal excessive spending proposed by the SPD and the Greens by including a provision for so-called global unallocated funds (Globale Minderausgabe).[18] He also went so far as to commission an expert opinion on the constitutional validity of expenditures proposed by the SPD and the Greens. The inability to reach a consensus on the budget and the debt brake led to the collapse of the ruling coalition on 6 November 2024, when the chancellor dismissed the finance minister.

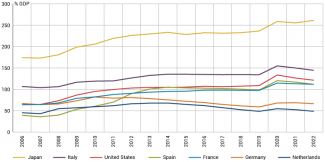

Austerity policies could deepen the crisis, and there are no compelling economic arguments for maintaining them beyond adherence to principles established by previous governments. Currently, Germany’s public debt stands at approximately 63% of GDP, significantly lower than in many other EU countries, the United States, and Japan (see Chart 7). The government still has scope to substantially increase borrowing, with an additional €48 billion available under the new EU fiscal rules introduced in April 2024.[19]

Chart 7. Public debt for selected countries

Source: ‘Gross public debt, percent of GDP’, International Monetary Fund, imf.org.

The debt brake in the election campaign: forecasts

The future coalition configuration will determine the significance of the debt brake and its potential reform in public debate. The Christian Democrats (CDU/CSU), who are leading in the polls, would naturally partner with the FDP; however, it remains uncertain whether the party will surpass the 5% electoral threshold. Meanwhile, the cordon sanitaire around the AfD means that the party is not viewed as a viable coalition partner. Consequently, the most likely coalition line-ups following the 23 February election are the CDU/CSU with the SPD or the CDU/CSU with the Greens. In both scenarios, reforming the debt brake appears feasible, as continuing to circumvent it would render this fiscal rule effectively meaningless and undermine the government’s credibility. At the same time, ignoring immediate investment needs seems unfeasible in the face of a prolonged crisis and growing calls from economists to increase public investment.

In its election manifesto, the CDU/CSU advocates maintaining the debt brake in its current form. However, the party may show flexibility in coalition negotiations, as internal discussions about reforming the instrument at the state level were already taking place in the summer of 2024. One proposed modification involved lowering the debt brake threshold to 0.15% of GDP. Christian Democratic minister-presidents of federal states have also expressed the need to revise the rules governing the instrument,[20] as many states are facing economic difficulties. In North Rhine-Westphalia, 348 municipalities consider their budgetary situation poor, while Schleswig-Holstein is on the brink of a financial crisis, with an estimated shortfall of approximately 1 billion euros for current expenditures in 2025.

The SPD and the Greens advocate for reforming the debt brake by easing its restrictions, specifically by excluding investments from its limits. This would allow both investment and social expenditure to be accommodated within the budget. In their election manifestos, both parties propose measures such as a 10% investment bonus for businesses, maintaining the citizen’s allowance, and increasing spending on research and development. However, implementing this approach would require a precise definition of what qualifies as investment, which could be problematic. A strict definition might constrain government flexibility and complicate budget management.

Experts have suggested alternative proposals. One proposal involves reintroducing the debt brake gradually after economic crises, as economies rarely return to stable growth immediately. Another suggestion is to link annual borrowing limits to the overall level of public debt, allowing for a higher borrowing cap when total debt is relatively low. An alternative approach involves creating an investment fund enshrined in the Basic Law. Under this system, interest payments on loans from the fund would be covered by the regular budget. This measure would balance the need for public investment with maintaining a fiscally responsible and stable federal budget.

Other proposals include suspending the debt brake again due to extraordinary circumstances, although the current situation does not warrant such a decision. This measure would require the prior approval of the federal budget, which is unlikely to occur before mid-2025. Since 1 January, Germany has been operating on a provisional budget, and following the formation of a new government, it will take several more months before a full budget is drafted and passed. Given the need to reach a compromise among future coalition partners, the legal solutions discussed above will likely be considered during negotiations on the debt brake.

[1] A rule stipulating that only investment spending may be financed through a budget deficit.

[2] This was when a global economic slump occurred, triggered by the bursting of the US housing market bubble. This resulted in a crisis in the financial sector as a whole. The collapse of several financial institutions and the freezing of lending activity triggered a global recession.

[3] See ‘Convergence criteria’, European Central Bank, ecb.europa.eu.

[4] See K. Popławski, ‘Niemcy: nowe instrumenty pomocowe dla gospodarki’, OSW, 25 March 2020; idem, ‘Gospodarka Niemiec – pandemiczne uderzenie i jego konsekwencje’, Komentarze OSW, no. 335, 27 May 2020, osw.waw.pl.

[5] The surge in popularity of the new trend in classical economics was driven by stagflation in many Western economies in the 1970s, which in turn resulted from oil crises and an excessive supply of money. The neo-liberal shift was based, among other factors, on reducing the state’s role in the economy and curbing inflation.

[6] S. Holzmann et el., ‘Staatsfinanzen im Fokus – wie Megatrends, Kriege und Krisen den Fiskus herausfordern’, Bertelsmann Foundation, 15 November 2024, bertelsmann-stiftung.de.

[7] D. Landmesser, ‘Brückensanierung wird teurer als gedacht’, Tagesschau, 8 April 2024, tagesschau.de; ‘Zusätzliche Milliarden Euro für die Schiene’, Die Bundesregierung, 14 June 2024, bundesregierung.de.

[8] ‘Gut jeder dritte Fernzug der Deutschen Bahn 2024 verspätet’, Handelsblatt, 3 January 2025, handelsblatt.com.

[9] ‘In Deutschland fehlen 800.000 Wohnungen’, Frankfurter Allgemeine, 16 January 2024, faz.net.

[10] C. Kummerfeld, ‘Industrie: 40% der deutschen Firmen hegen Abwanderungspläne’, Finanzmarktwelt, 1 August 2024, finanzmarktwelt.de.

[11] ‘Zahl der Firmeninsolvenzen 2024 stark gestiegen’, Tagesschau, 10 January 2025, tageschau.de.

[12] ‘22 Prozent der Arbeitszeit für Bürokratie nötig’, ifo Institut, 4 December 2024, ifo.de.

[13] ‘$369 billion in investment incentives to address energy security and climate change’, Investment Policy Hub UNCTAD, 16 August 2022, investmentpolicy.unctad.org.

[14] ‘Chinese-owned brands’ passenger vehicle exports expected to reach 4.5 million in 2024’, Canalys, 20 November 2024, canalys.com.

[15] A financial support system that came into effect on 1 January 2023, replacing the Hartz IV benefit. It is intended to guarantee a minimum income to individuals in financial difficulty who lack sufficient funds to support themselves.

[16] These are auxiliary budgets created separately from the main federal budget. They are established to meet specific purposes and managed independently of other expenditure. See S. Płóciennik, ‘A shadow budget. Germany increases spending through special funds’, OSW Commentary, no. 546, 16 October 2023, osw.waw.pl.

[17] See M. Kędzierski, S. Płóciennik, ‘Germany: the Constitutional Court deprives the government of €60 billion earmarked for transformation’, OSW, 17 November 2023, osw.waw.pl.

[18] The draft budget envisages that a portion of the planned expenditure will not be implemented, thereby reducing the gap between revenue and spending.

[19] L. Guttenberg et al., Luft nach oben: Wieso die EU-Fiskalregeln Spielraum für eine Reform der Schuldenbremse lassen, Bertelsmann Foundation, 12 December 2024, bertelsmann-stiftung.de.

[20] Daniel Günther (Schleswig-Holstein), Kai Wegner (Berlin), Reiner Haseloff (Saxony-Anhalt), Boris Rhein (Hessen), Hendrik Wüst (North Rhine-Westphalia) and Michael Kretschmer (Saxony).