Farewell to Europe: Gazprom after 2024

Russia is gradually advancing its ‘pivot to the East’ in natural gas exports, as evidenced by the growing importance of China, which has become Gazprom’s most significant market. The redirection of supply volumes to Asia is a necessity for the company, driven by its loss of market share in Europe following Moscow’s political decision to reduce gas transmission. However, over the coming years, the projected increase in sales to Asian buyers will not be sufficient to offset the company’s exit from Europe, either in terms of sales volumes or profit margins.

The long-term prospects for Gazprom’s increased presence in Asia and the restoration of its financial position remain uncertain. Achieving sustained growth would necessitate the development of new infrastructure, a process that is both capital- and time-intensive. Moreover, the company’s weakening bargaining power – resulting from its challenging financial situation and the increasing assertiveness of its partners – constrains its ability to negotiate favourable contracts, thereby affecting profitability. Consequently, it is highly likely that costs will be passed on to domestic consumers. Nevertheless, the Russian government regards the expansion of its economic presence in Asia as a strategic priority. This implies that, irrespective of economic calculations, the gas industry’s ‘pivot to the East’ will continue and be framed as a success.

2024: compensating for some losses

During the 20th edition of the Gas of Russia International Forum in December 2022, representatives of the Russian government and the gas industry announced a ‘pivot to the East’ in natural gas exports. This shift was presented as a response to what they described as the global economy’s centre of gravity moving from the West to Asia, as well as to the anticipated decline in sales volumes in Europe.

Indeed, between 2021 and 2023 Gazprom recorded a negative trend in natural gas exports to European customers. However, this decline was not driven by objective factors but resulted from a political decision by the Kremlin to halt gas deliveries in an attempt to exert pressure on the EU. The politicisation of gas supplies had a severe impact on Gazprom’s financial standing, as well as on its production and sales figures. Consequently, in 2023, the total volume of exports to the states of the so-called ‘far abroad’[1] decreased by almost 115 bcm compared to the 2021 figures, i.e. by approximately 60%, despite the increase in supplies to China.

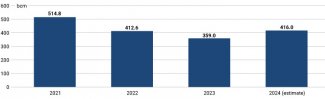

In 2024, Gazprom managed to reverse the downward trend. According to a statement by Gazprom CEO Aleksei Miller on 26 December, the Russian gas giant extracted approximately 416 bcm of natural gas, an increase of nearly 16% compared to 2023. Miller also provided estimates for annual gas transmission volumes to China (31 bcm) and domestic deliveries (390 bcm), the latter including gas sold through Gazprom’s network by other companies or resold by the corporation itself. Thus, 2024 was the first year, following two consecutive years of decline, that Gazprom recorded growth in both production and total exports.

Chart 1. Gazprom’s production from 2021 to 2024

Source: Gazprom.

The reversal of the negative trend described above is the result of several factors, primarily the increase in sales to China (up 36% y/y) and Europe (up 13% y/y). To a lesser extent, Gazprom’s improved performance was driven by increased deliveries to Central Asia, including exports to Uzbekistan under a June 2023 agreement stipulating annual supplies of 2.8 bcm, as well as increased sales to Kazakhstan. Higher export volumes will have a positive impact on the company’s financial balance, particularly in comparison to the exceptionally difficult year of 2023.[2]

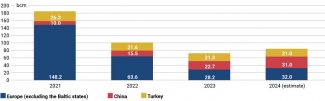

Chart 2. Gazprom’s exports to the so-called far abroad countries from 2021 to 2024

Source: the author’s own calculations based on figures published by Gazprom and the Turkish Energy Market Regulatory Authority (EPDK).

Prospects until 2028: Asia’s growing importance to Gazprom

In the medium term, Gazprom’s foreign sales are likely to decline again in 2025 before beginning to recover. The decline in export volumes will be driven by the cessation of gas transit through Ukraine. In 2024, Russia transported over 16 bcm of gas via this route, accounting for approximately 19% of the company’s total sales to the so-called far abroad countries and about half of its shipments to Europe.[3] Without resuming exports through Ukraine or securing an alternative European route, Gazprom will be left with only one operational pipeline serving this market: a single line of the TurkStream gas pipeline, with a nominal capacity of 15.75 bcm per year.[4] Notably, according to media reports, Gazprom’s internal strategic documents do not envisage any transit through Ukraine in 2025.[5]

The decline in Gazprom’s market share in Europe has led to a greater reliance on Asian buyers, particularly the People’s Republic of China. Once the Power of Siberia-1 gas pipeline reaches its planned capacity of 38 bcm per year in 2025, China will become Gazprom’s most important customer. Furthermore, by 2027, exports along this route will rise by a further 10 bcm following the launch of the so-called Far Eastern route to China. Through these two pipelines, Gazprom will be capable of supplying approximately 50 bcm of natural gas per year.

The Russian gas monopoly is also expected to expand exports to other buyers in Central Asia. Currently, one line of the Central Asia–Centre pipeline is being expanded southward, aiming to boost the capacity of the existing infrastructure from the current 3 bcm to 10–12 bcm annually by 2025. According to agreements signed in 2024, Gazprom will be able to supply approximately 11 bcm per year to Uzbekistan from 2026, along with 1 bcm annually to Kyrgyzstan, although the planned date for launching the supplies to the latter country remains uncertain.[6] Sales will be conducted via transit through Kazakhstan, and discussions on a potential increase in volumes are reportedly already underway.

In addition to the Chinese and Central Asian markets, an increase in gas exports to Turkey cannot be ruled out. By fully utilising the spare capacity of the Black Sea pipelines, Russia could supply an additional 10–11 bcm per year, which could potentially become the subject of new contracts. The two currently valid agreements between Gazprom and Turkey’s BOTAŞ, covering 16 bcm of gas annually transported via the Blue Stream pipeline and 5.75 bcm annually via TurkStream, are set to expire at the end of 2025.

If Gazprom successfully executes its expansion plans across all Asian markets, its gas exports to Asia could increase by approximately 40 bcm in 2027 compared to the volume sold in 2024. However, a key consideration is that sales to the Asian market generate significantly lower revenues than those to European customers,[7] which will affect the company’s financial performance. Additionally, an increase in gas shipments to Turkey is far from certain. Since 2022, Turkey’s imports of Russian gas have remained relatively stable due to a steady increase in domestic production and ongoing diversification of supply sources.[8] In November 2024, Turkey’s minister of energy reaffirmed that this diversification strategy would continue.[9]

The decline in export revenues will continue to be mitigated by increased domestic sales, a development that both Gazprom and the Kremlin portray as a success in line with efforts to expand gasification across the country. However, this process also has a downside, namely the ongoing gradual transfer of costs onto domestic consumers. Gas price adjustments beginning in 2022, along with another planned increase in 2025, will lead to a cumulative rise in gas prices for Russian consumers of more than a third compared to pre-invasion levels.[10] Moreover, Gazprom is actively advocating for further rate increases to safeguard the profitability of domestic supply. This includes proposals to unfreeze distribution costs, thereby further raising the final price for consumers.[11]

Gazprom beyond 2028: expectations from Beijing...

The long-term prospects for further export growth and the full implementation of the gas ‘pivot to the East’ remain uncertain beyond the next two to three years. For Gazprom, the key challenge involves securing the capability to redirect natural gas from West Siberian fields, which have traditionally supplied the European market, towards Asia. Replacing the ‘lost’ volumes in Europe, even to a comparable extent, will only be possible if exports to China increase significantly, as the Chinese market is the sole viable alternative capable of absorbing such large quantities of gas.

For this reason, Russian authorities prioritise China as Gazprom’s most important customer, pushing forward the Power of Siberia-2 gas pipeline project. This planned connection, with a proposed capacity of 50 bcm per year, is intended to transport gas from West Siberian fields via Mongolia. However, the project remains in its design phase, and according to media reports, Russia and China have yet to agree on a pricing formula. In an attempt to break the deadlock, in November 2024 Moscow announced that it was considering an alternative route to China, with a capacity of 35 bcm annually,[12] passing through eastern Kazakhstan. This proposal is a variation of the Altai Gas Pipeline initiative, which was initially proposed in the early 21st century. Beijing has yet to respond to this idea.

The lack of an agreed pricing formula for the Power of Siberia-2, along with Russia’s proposals for an alternative pipeline, suggests that expanding its presence in the Chinese market on terms favourable to Gazprom is a significant challenge for Moscow. Beyond the loss of revenue and influence in Europe, exiting the Western market has another major consequence, namely, it weakens Gazprom’s bargaining position. The company is now forced into a frantic search for new export markets.

China is exploiting this weakness in negotiations. According to media reports, Beijing is demanding that Russia sell gas at domestic Russian prices, fully aware that the pipeline project has become a critical priority for both Gazprom and the Russian government. Moreover, China is in no hurry to increase imports from Russia, as it continues to diversify its supply sources and expand domestic gas production. This, in turn, forces Moscow to make difficult adjustments to its expectations. In effect, the prospect of fully replacing the European market with the Chinese one, both in terms of volume and profitability, appears unlikely.

It is possible that the Power of Siberia-2 pipeline will be constructed primarily for political reasons. China may regard a high-capacity land connection as a raw material ‘insurance policy’ in the event that supplies from other sources, such as Australian LNG, are disrupted, particularly in the context of a potential conflict over Taiwan. At the same time, it is likely that Beijing would seek a more flexible contract, securing a stable but relatively low baseline supply with the option for additional deliveries ‘on demand’. Compared to Gazprom’s original plans for an annual transmission of 55 bcm, such an arrangement would be far less favourable for Russia.

...and the Central Asian partners

Alongside its efforts to expand its presence in China, Gazprom is seeking long-term markets in other parts of Asia. Central Asia remains one such region, particularly important for Russia due to the potential to access China through the region’s infrastructure. The ‘gas union’ concept proposed by Russia was seemingly at least partly motivated by this objective.[13] For this reason, Gazprom considers Central Asian countries significant markets, despite considerably lower profit margins compared to other export destinations.

In addition to the proposed gas pipeline to China via eastern Kazakhstan, Gazprom is also considering accessing the Chinese market through existing infrastructure in Central Asia, using swap transactions via the Central Asia–China pipeline. From Russia’s perspective, this would be the most economically viable solution, as expanding existing pipelines would require significantly less investment than constructing entirely new direct connections to China. However, this approach would leave key pipeline sections outside Russia’s control, something Moscow had attempted to address through the proposed ‘gas union’, an initiative that has so far failed to materialise.

The main obstacle to implementing this scenario, aside from the need to secure guarantees from China for gas purchases, is the stance of Central Asian partners themselves. Both Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan view cooperation with Gazprom primarily as a commercial matter, which restricts Russia’s ability to influence them in securing favourable transit conditions. Furthermore, Russia’s ambitions are complicated by Turkmenistan’s role as a key supplier of gas to China via Central Asia’s pipeline network. Ashgabat remains firmly opposed to granting Gazprom access to the Central Asia–China pipeline.

Turkey, Iran and LNG: uncertain variants

Turkey is another potential transit route being considered by Moscow. However, Ankara’s ongoing efforts to diversify its gas imports (through LNG supplies and cooperation with Turkmenistan), as well as its decision to maintain Russian imports at a relatively stable level since 2022, suggest a low demand for additional volumes from Gazprom. Simultaneously, the prospect of re-exporting Russian gas, primarily to Europe, through Turkey as a gas hub, remains an attractive option for Gazprom, as it could enable Russia to maintain an indirect presence in the EU market.

It is possible that the EU will actively seek to prevent this scenario, in line with its stated goal of fully phasing out Russian hydrocarbon imports. Moreover, significantly increasing gas imports to Turkey beyond the current capacity of 32 bcm annually would necessitate expanding infrastructure connections, requiring substantial investment and a lengthy implementation timeline.

Iran is another route being considered by Gazprom. In 2024, the company signed a memorandum with Iran’s National Iranian Gas Company (NIGC) on the supply of Russian gas to the country. A year later, following the signing of a new Iran-Russia treaty in January 2025, Russian Energy Minister Sergei Tsivilev announced plans to export up to 2 bcm annually in the initial phase, with a long-term goal of reaching 55 bcm per year. The gas is expected to be transported via Azerbaijan. According to Russian statements, final discussions on launching the 2 bcm supply are underway, with the pricing formula as the last outstanding issue to be resolved.

While the initial export of a small volume of gas does not require infrastructure investments, any significant increase in gas transmission would necessitate significant financial outlays, likely including investments in Azerbaijan. From Moscow’s perspective, entering the Iranian market could ultimately facilitate further sales to Pakistan and India. However, this remains a long-term prospect fraught with significant challenges, particularly political and infrastructural.

The prospect of Gazprom increasing its exports through its own LNG supplies also remains uncertain. Currently, the company produces LNG at two facilities: Sakhalin-2 (where it holds a majority stake;[14] with a production capacity of 9.6 million tonnes annually) and Portovaya LNG (with a capacity of 1.5 million tonnes annually). The Sakhalin-2 facility, situated on Sakhalin Island, serves exclusively the Asian market, and in 2023, over half of its production was exported to Japan, with the remainder sent to China and South Korea.[15] Meanwhile, the Portovaya LNG plant, located in the Baltic Sea, was constructed to supply Russia’s Kaliningrad Oblast and support planned exports to the European market.[16]

Despite Russia’s efforts, its technological shortcomings and the Western sanctions regime targeting the LNG sector hinder its stable development.[17] Moreover, Gazprom faces domestic competition from another Russian company, Novatek. Unlike Novatek, the state-owned giant has never initiated liquefied natural gas production using its own technology. Gazprom acquired a majority stake in the Sakhalin-2 project by taking over the shares of a foreign investor. Meanwhile, the mid-scale Portovaya LNG plant, launched in 2022, was developed with technological support from a non-Russian partner. Other planned projects remain at the design stage, and the continued pressure of sanctions further diminishes their chances of materialising.

Conclusions: the ‘pivot to the East’ is successful only in theory

A significant increase in gas exports beyond 2027 remains uncertain, and the restoration of Gazprom’s position through its ‘pivot to the East’ appears unlikely. The company’s uncertain future is a direct consequence of the political decision to halt gas supplies to the EU. By withdrawing from Europe, the Russian gas monopoly not only lost its most profitable customers but also found itself in a desperate search for alternative markets. This has weakened Gazprom’s bargaining position, leaving China as its only viable alternative. Even if gas exports to China expand via the Power of Siberia-2 pipeline, the success will be limited. While this may partially compensate revenue losses from Europe, it will also render Gazprom’s export structure heavily reliant on a single buyer.

Intermediate solutions, such as delivering gas to China via Central Asia or increasing sales to other Asian countries, are fraught with challenges, primarily due to the requirement for extensive infrastructure expansion. Additionally, Gazprom faces competition from other suppliers in every Asian market, while importing countries actively seek to diversify their energy sources. Notably, they aim to avoid repeating the mistakes of certain European states that became overly dependent on Russian gas. Furthermore, broader decarbonisation trends, which are also gaining momentum in Asia, pose another long-term obstacle to Gazprom’s ambitions.

If Gazprom were to attempt resuming gas transit to Europe in the future, assuming a political climate favourable to Russia emerges in European capitals, it is clear that a return to previous export volumes and corresponding revenues would be impossible. This is due to a combination of infrastructural and political barriers (such as resuming gas transit and ensuring the operational capacity of certain pipelines), the diversification of the EU’s energy mix, and the pace of decarbonisation efforts. Under these circumstances, it is difficult to imagine European buyers signing long-term contracts similar to those that once cemented Gazprom’s dominance on the continent. Moreover, re-establishing deep business ties with an entity that has previously violated contractual obligations in an aggressive manner would pose a significant risk to supply security.

In light of these challenges, the need to reformulate Gazprom’s business model – and, consequently, Russia’s gas market – is becoming increasingly urgent. The decline in export revenues casts doubts about the sustainability of domestic sales conducted at artificially low prices, as evidenced by the scale of Russia’s domestic gas price increases since 2022. Regardless of how swiftly new export markets are secured, the process of ‘realignment’ in the domestic gas market will persist. This will be further exacerbated by Russia’s deteriorating economic situation.

At the same time, the Russian authorities will continue to portray Gazprom’s activities as a success, whether by emphasising the ongoing gasification of the country, highlighting growing domestic sales, or announcing new contracts with foreign clients. In reality, however, the so-called gas ‘Pivot to the East’ comes at a high cost for Gazprom, which previously enjoyed a privileged position in Europe. Achieving a similar status in new markets under completely different political conditions appears unfeasible.

Table. Russian pipelines transporting gas to the so-called far abroad states

Source: the author’s own calculations based on figures published by Gazprom and OGTSU.

[1] That is, to Europe (excluding the Baltic states: Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia), China, and Turkey.

[2] In 2023, for the first time since 1999, Gazprom recorded a loss amounting to 629 billion roubles (around $7 billion). The decline was mainly due to a drop in sales in the gas segment, whose revenue decreased by almost half due to Gazprom’s loss of a significant share of the European market and lower gas prices. See F. Rudnik, ‘Gazprom in 2023: financial losses hit a record high’, OSW, 14 June 2024, osw.waw.pl.

[3] See A. Łoskot-Strachota, S. Matuszak, F. Rudnik, ‘Game over? The future of Russian gas transit through Ukraine’, OSW Commentary, no. 623, 6 September 2024, osw.waw.pl.

[4] It is possible that the exported volume of gas will exceed the nominal capacity, as according to media reports, between 1 and 26 January 2025, a record high volume of 1.425 bcm of gas was transported via this route. If this pace is sustained and the necessary maintenance work is carried out, Gazprom could be sending approximately 18.5 bcm of gas annually to the EU.

[5] ‘Exclusive: Gazprom 2025 plan assumes no more transit via Ukraine to Europe, source says’, Reuters, 26 November 2024, reuters.com.

[6] Т. Дятел, ‘«Газпром» закрепился в Средней Азии’, Коммерсантъ, 7 June 2024, kommersant.ru.

[7] According to forecasts from the Ministry of Economic Development of the Russian Federation, disclosed by the media in September 2024, the average price of 1,000 m3 of natural gas in 2025 will be $261 for Chinese recipients and $340 for Western recipients (i.e. mainly those from Europe). Although no information was provided regarding the price of gas exported beyond the so-called far abroad, it is certain that this price is much lower. According to media reports, in 2023 Gazprom was selling gas to Uzbekistan at $160 per 1,000 m3. For comparison, at that time the average price paid by China was $286.9 (according to figures provided by the Ministry of Economic Development of the Russian Federation).

[8] See A. Michalski, A. Łoskot-Strachota, ‘Turkey: opportunities and challenges on the domestic gas market in 2024’, OSW, 3 June 2024, osw.waw.pl.

[9] D. O’Byrne, ‘Turkey nearing ‘critical’ phase in gas supply arrangements: minister’, S&P Global, 11 October 2024, spglobal.com.

[10] ‘«Газпром» пожаловался на нехватку денег и потребовал поднять цены на газ для россиян’, The Moscow Times, 23 January 2025, moscowtimes.ru.

[11] ‘Внутренние цены на газ в России должны позволять "Газпрому" инвестировать в проекты’, Интерфакс, 23 January 2025, interfax.ru.

[12] The media also speculated that the pipeline’s capacity could be increased to 45 bcm/annually. See ‘Новак: РФ и Китай рассматривают новый газовый маршрут через Казахстан’, TACC, 15 November 2024, tass.ru.

[13] In 2022, the Russian leadership approached two Central Asian states (Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan) with an offer involving the establishment of a trilateral ‘gas union’ which Moscow presented as an initiative to develop joint regulations allowing for a more efficient gas transmission between the parties involved. The concept was not received positively by Astana and Tashkent due to their fears that Gazprom could seize control of transmission infrastructure running through these countries. For more see M. Popławski, F. Rudnik, ‘Russian gas in Central Asia: a plan to deepen dependence’, OSW, 31 October 2023, osw.waw.pl.

[14] Since 2024, Gazprom has owned a total of 77.5% of shares in the Sakhalinskaya Energiya company that manages the facility. In March 2024, the Russian government allowed the company to purchase 27.5% of shares previously owned by Shell, which announced its intention to withdraw from the project following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine (previously, from 2006, Gazprom held 50% plus one share in the company). The shareholders also include two Japanese companies: Mitsui & Co., Ltd. (12.5%) and Mitsubishi Corporation (10%).

[15] A. Kawasaki, M. Li, ‘Russia’s Sakhalin Energy offers 12 term LNG cargoes a year to Chinese buyers’, S&P Global, 22 February 2024, spglobal.com.

[16] The Portovaya LNG facility was launched in 2022. Since then, the LNG produced there has undergone regasification in Kaliningrad Oblast or has been sold at European terminals. On 10 January 2025, the facility was put on the US sanctions list, which prevents it from exporting gas to Europe due to the threat of secondary sanctions. The prospect of selling gas to Asia seems unlikely because it requires a much longer supply route, while the reception of the cargo is uncertain. This, in turn, significantly reduces the profitability of this initiative.

[17] See F. Rudnik, ‘The effect of the sanctions: the Russian LNG sector’s problems’, OSW Commentary, no. 578, 7 March 2024, osw.waw.pl.