The vanishing Balkans. The region’s demographic crisis

The demographic situation in the six Western Balkans countries (WB6): Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH), Montenegro, Kosovo, North Macedonia, and Serbia, has been marked by a steady decline in population over the past two decades. During this period, the region’s population has decreased by nearly 2.5 million and now stands at just over 16 million. Due to the challenges of economic and political transition, as well as the conflicts of the 1990s, one in five WB6 citizens now lives abroad. In addition to common issues typically faced by less developed countries, such as emigration, the region is also struggling with a challenge more characteristic of wealthier nations: low birth rates. Due to growing labour shortages, the Western Balkans are an increasingly popular destination for immigrants. Foreign workers, particularly from Southeast Asia, are finding employment in sectors such as construction, agriculture, tourism, and healthcare. Governments across the region have implemented crisis-response measures, but these are largely short-term solutions that fail to address systemic problems. Consequently, demographic projections for the WB6 countries are bleak. According to the UN, the region’s population is expected to shrink by a further 3 million by 2050. The largest losses are forecast for BiH (-22%), Albania (-19.5%), and Serbia (-18%).

The complicated (post)war arithmetic

In the 1990s, the Western Balkans were the scene of intense armed conflicts triggered by the breakup of Yugoslavia. The wars in Croatia, BiH, and Kosovo, marked by ethnic cleansing and mass displacements, led to significant population losses and lasting demographic shifts in the region. These events resulted not only in depopulation but also in long-term social and economic transformations, the consequences of which are still felt today. Analysing the demographic impact of this period is particularly challenging because the available data is incomplete and inconsistent. The chaos of war, the dismantling of institutions responsible for population registration, and large-scale migration have made it difficult to accurately assess the scale of demographic changes that took place in the final years of the 20th century.

In 1991, BiH had a population of 4.3 million, according to the census conducted just prior to the breakup of Yugoslavia. During the brutal three-and-a-half-year conflict, over 100,000 people were killed, and more than 2 million were forced to flee their homes. Approximately 1.2 million of these individuals emigrated as refugees, while the rest became internally displaced. After the 1995 peace agreement, some citizens returned to the country; however, BiH nevertheless lost a significant portion of its pre-war demographic potential. Ethnic tensions have also complicated population data collection in the following decades, with the only official census taking place in 2013. In this ethnically divided country, the size of specific national groups remains a crucial factor in political debates regarding its future, rendering census-taking a highly politicised process.[1] Consequently, estimates of BiH’s population rely on assessments prepared by demographers, which vary significantly. North Macedonia has faced similar challenges. A planned 2011 census was cancelled due to intense ethnic tensions and was only successfully conducted a decade later, in 2021.

The issue with demographic statistics compiled back in the 1990s is particularly evident in Kosovo. According to the 1981 census, this Yugoslav province was inhabited by 1.58 million people. However, in 1991, two years after Slobodan Milošević revoked its autonomy, Kosovo Albanians boycotted the census, leaving the Yugoslav authorities to estimate the population at 1.95 million. Errors in this estimation, such as the application of outdated fertility rates, led to significant discrepancies in subsequent counts. When the first post-war census was conducted in 2011, the recorded population was significantly smaller than previously assumed (this time, Kosovo Serbs boycotted the process).

In the 1990s, Serbia’s population did not decline significantly due to the influx of ethnic Serbs from newly independent states that emerged after the breakup of Yugoslavia. This migration partially offset the demographic losses of the decade. According to the 1991 Yugoslav census, Serbia (excluding Kosovo) had a population of 7.8 million. Over the next decade, this number decreased by approximately 300,000. During this period, many residents emigrated due to an economic crisis (including hyperinflation), political repression under Slobodan Milošević, and forced military conscription. Despite persistently low birth rates since the 1970s, insufficient to ensure generational replacement, Serbia managed to maintain relative population stability owing to the arrival of successive waves of Serbian refugees. In 1998 alone, the country[2] hosted over half a million refugees from Croatia and BiH,[3] and after 1999, these people were joined by Serbs fleeing Kosovo.

The shrinking population in the 21st century

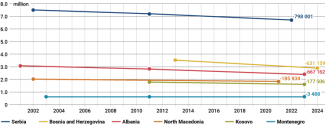

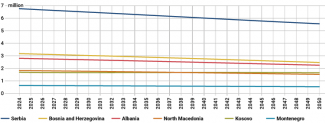

Today, the Western Balkans are struggling with a continuous decline in the number of inhabitants and an ageing population. In 2002, Serbia had a population of 7.49 million, according to the census. Since then, the population of the most populous post-Yugoslav country has been decreasing by an average of approximately 40,000 individuals annually. According to the most recent census, conducted in 2022, Serbia now has 6.7 million citizens, 10% fewer than two decades ago.

BiH and Albania are experiencing the most significant population declines in the region. The first and only post-war census in BiH, conducted as late as 2013, recorded a population of 3.5 million.[4] According to the World Bank, the country now has 3.1 million inhabitants, while some Bosnian demographers suggest a figure closer to 2.9 million. The most pessimistic assessments go as low as a mere 2 million.[5] Thus, depending on the data source, BiH’s population has decreased by either 11% or 17%, and in the most pessimistic variant, the country may have lost up to 40% of its population over the past decade.

Albania faces a similarly unfavourable demographic trend, with a steadily declining population since the fall of Enver Hoxha’s communist regime. According to the 2001 census, the country had just over 3 million inhabitants. A decade later, this number had already fallen by nearly 250,000, reaching 2.83 million. The most recent census, conducted in 2023, estimates the population at 2.4 million, a 21% decline since the beginning of the millennium.

Kosovo, Europe’s youngest state, is also experiencing a population decline. The first census conducted after its declaration of independence, in 2011, recorded a population of 1.79 million. According to figures compiled by the Kosovo Agency of Statistics and preliminary results from the 2024 census, the population has since fallen to 1.58 million – an 11% decrease over 13 years. North Macedonia faces a similar challenge, having lost 9% of its population between 2002 and 2021. The country currently has 1.83 million inhabitants. A notable exception in the region is Montenegro, the smallest Western Balkan state by population. Over the past decades, its population has remained relatively stable. In 2011, the country had 625,000 inhabitants, and by 2023, this number had increased slightly to 633,000. However, this modest increase is not the result of natural population growth, as despite having the highest birth rate in the region, Montenegro still falls below the replacement level. Instead, the rise is mainly driven by immigration, particularly from Russia (especially after its partial mobilisation announcement in 2022) and Turkey. According to the Montenegrin Ministry of Internal Affairs, between January and March 2023 alone, 64,000 Russian citizens registered for temporary residence, with a third of them obtaining a permanent residence permit.[6] Currently, approximately 80,000–90,000 foreign nationals reside permanently in Montenegro, accounting for 10–14% of the country’s population.

Chart 1. WB6’s population after 2000

Source: statistical offices of Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kosovo, Montenegro, North Macedonia and Serbia.

Low birth rates

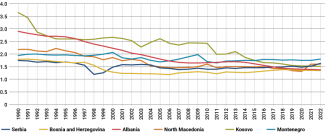

The demographic challenges faced by the Western Balkan states are further exacerbated by persistently low fertility rates. Even Kosovo, which for years had one of the highest birth rates in the region, is no longer an exception. The marked decline in fertility is the key factor distinguishing the region’s population trends of the 1960s and 1970s from those of today (although some Yugoslav republics, such as Serbia, already had low fertility rates during that period). At that time, the overall demographic profile of the Western Balkans was typical of poorer countries, characterised by high emigration offset by strong birth rates.

Over the past two decades, the trend of declining birth rates has continued in Serbia, BiH, Montenegro, and North Macedonia. However, the most dramatic shift has occurred in Kosovo and Albania. At the beginning of the 21st century, these two countries still maintained birth rates sufficient for generational replacement. Twenty years later, their fertility rates have nearly converged with those of the rest of the region.

None of the WB6 countries currently has a fertility rate above 2.1, the threshold needed for generational replacement. The average number of children per woman of childbearing age in the region is approximately 1.5, roughly the same as the EU average (1.46 in 2022). As in the EU, this decline is associated with broader social and economic transformations, shifting priorities among younger generations, a decrease in marriage rates, and challenges related to childcare. In addition, factors such as persistent political tensions maintained by ruling elites and the low quality of public services further discourage WB6 citizens from having more children.

Chart 2. Fertility rates recorded in WB6 states

Source: ‘World Development Indicators’, The World Bank, databank.worldbank.org.

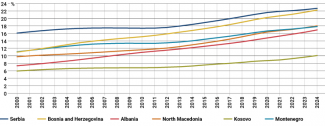

An ageing population

The combination of low fertility rates and the emigration of young people, particularly during the wars of the 1990s, has resulted in a rapidly ageing population in all WB6 states. In three countries: BiH, Serbia, and North Macedonia, the median age is close to or even higher than the EU average of 44.5 years. The proportion of individuals aged 65 and over is also rising rapidly across the Western Balkans. Serbia and BiH have the highest share of elderly residents, with this group comprising 20% of the population in both countries. The rest of the region is also ageing quickly, though Kosovo stands out as an exception, with only 10% of its population aged 65 and over.

The growing proportion of elderly citizens presents significant economic and political challenges. The declining share of the working-age population limits economic growth, while the increasing number of pensioners places additional strain on already overburdened pension systems across the WB6 countries.

The rising costs of healthcare are creating financial challenges for national budgets across the region. In 2021, North Macedonia allocated 8.5% of its GDP to healthcare, an increase of 2 percentage points compared to three years earlier. Montenegro witnessed an even more significant rise, with healthcare spending increasing from 7.9% of GDP in 2011 to 10.5% in 2021.[7] From a political perspective, an ageing population increases pressure to reform social welfare and pension systems, which are often underdeveloped.

Table 1. Median age of WB6 residents

Source: Eurostat data, excluding BiH (UN data) and Kosovo (data published by the Kosovo Agency of Statistics after: ‘The preliminary data of the Census of Population, Family Economies and Housing in Kosovo are published’, Prime Minister Office, kryeministri.rks-gov.net).

Chart 3. Share of individuals aged 65 and over in total population

Source: ‘Population estimates and projections’, The World Bank, databank.worldbank.org.

Emigration and the brain drain

Emigration is not a new phenomenon for the Western Balkans. The region has long faced large-scale population outflows. For instance, in the 1960s and 1970s, the so-called Gastarbeiter (guest workers) migrated in large numbers to West Germany in search of employment. Another wave of emigration occurred in the 1990s due to the turbulent breakup of Yugoslavia and the collapse of Albania’s communist regime. After 2000, persistent high unemployment and the significant wage gap between the region and the EU provided further incentives to emigrate. Consequently, the Western Balkans experienced a steady outflow of skilled workers (including plumbers, carpenters, and drivers), who found higher wages and better working conditions abroad.

However, economic factors are not the only incentive to emigrate. A 2022 OECD report highlights several additional reasons for relocation, including the low quality of education, healthcare, and the judicial system, as well as the incompetence of the political elite, an unfavourable business environment, and endemic corruption.[8]

The organisation also reports that over 20% of WB6 citizens live and work abroad. In this unfortunate ranking, Bosnia and Herzegovina stands out both within the region and globally, with as many as 49% of its citizens residing abroad. The situation is not much better in other Western Balkan countries: 44% of Albanians, 34% of North Macedonians, and 21% of Montenegrins live outside their home countries. Serbia has the smallest diaspora in relative terms, with 15% of its population living abroad.[9]

Table 2. Main destinations for emigrants from the WB6 countries

Source: OECD data, data-explorer.oecd.org.

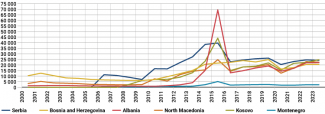

High emigration from the WB6 is also a result of the growing demand for skilled labour in EU countries, particularly Germany. In 2015, Germany introduced procedures to facilitate the issuance of work visas for Western Balkans citizens. This initiative aimed to provide a legal alternative for individuals who might otherwise enter the country illegally and apply for asylum. As of June 2024, the annual quota of work visas granted to residents of the region stands at 50,000.[10] This figure does not include regulated professions, such as physicians, meaning that even more individuals from the WB6 states are eligible to enter the German labour market. Workers from the Western Balkans account for a quarter of Germany’s total foreign medical staff (over 42,000 individuals in 2020).

Migration from the Western Balkans to Germany has shown a clear upward trend, though its dynamics have fluctuated due to various economic, political, and social factors.[11] A noticeable acceleration occurred after 2010, coinciding with Germany’s economic recovery following the 2008–2009 financial crisis. The peak was reached in 2014–2015, during the European migration crisis and the rise of the so-called Western Balkan route. At that time, the Bundestag liberalised visa regulations for citizens of the region’s states. During this period, Albanians and Kosovars, facing severe economic difficulties, were the primary beneficiaries of the opportunity to relocate to Germany. The COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 temporarily disrupted this trend due to global mobility restrictions. However, migration quickly returned to previous levels once the restrictions were eased, demonstrating the sustained demand for access to the German labour market.

Chart 4. Emigration from the WB6 states to Germany

Source: Federal Statistical Office of Germany.

The pace and intensity of the brain drain place the WB6 among the countries most affected by this phenomenon. The outflow of skilled workers has had disastrous consequences for the region’s economic and social development. According to research conducted by the World Economic Forum, BiH ranks among the worst in the world for talent retention, a global competitiveness index measuring a country’s ability to keep its most talented individuals. The rating is based on a seven-point scale, where 1 represents the lowest score. BiH scores 1.8. Other Western Balkan countries fare only marginally better. North Macedonia scores 2.13, Serbia 2.27, and Albania 2.63. For comparison, Poland scores 3.17, the Czech Republic 3.76, and Switzerland, the highest globally, reaches 5.9.[12] Young people from the WB6 often plan their education with the job markets of their target countries in mind, further reinforcing the cycle of emigration and talent loss.[13]

Due to its geographical proximity and existing diasporas, young and educated residents of the region most frequently choose Germany, Austria, Italy, and Slovenia as their emigration destinations. Non-EU countries such as the United States and the United Kingdom are also popular. One of the key factors driving emigration is the persistently high unemployment rate among individuals aged 15–24. In 2023, youth unemployment stood at 28% in North Macedonia, Montenegro, and Albania, 26% in BiH, 24% in Serbia, and 17.3% in Kosovo.[14] For comparison, the EU average for this age group was 14.5%.[15]

The brain drain also imposes significant economic costs on the Western Balkans. These countries finance the education of young people who later contribute to the GDP of their destination countries rather than their place of origin. The cost of youth emigration from Albania, North Macedonia, and Montenegro is estimated to be as high as 3% of their GDP.[16] The shortage of highly skilled professionals in key sectors – such as IT, engineering, and healthcare further undermines the region’s ability to compete in the EU’s single market.

Immigration

Due to mass emigration and an ageing population, the WB6 countries are increasingly turning to foreign workers. The economic improvements over the past decade have made them relatively attractive destinations for individuals from poorer countries seeking better living and working conditions.

Serbia currently faces a shortage of around 50,000 workers, with projections suggesting that this number could double.[17] Other countries in the region are also struggling with significant labour deficits. Albania has a shortfall of 40,000 workers, BiH of approximately 30,000, and Montenegro of up to 25,000 during the peak tourist season. The most affected sectors include construction, tourism (especially in Albania and Montenegro), healthcare, and transport.

To attract more foreign workers, Serbia has simplified its work permit issuance procedures in recent years. In 2023, the country’s National Employment Service issued a total of 52,000 work permits, with the largest share going to Russian citizens (39%). They were followed by Chinese workers (20%), reflecting Belgrade’s growing economic cooperation with China, as well as Turks (10%) and Indians (10%). In other countries of the region, foreign workers primarily come from South and Southeast Asia, including India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Nepal, and the Philippines.

At the same time, wealthier Russians (particularly since 2022) and Turks have been relocating to the WB6, attracted by lower living costs and a socially welcoming environment. Russian immigration to Serbia accelerated after the outbreak of the war in Ukraine, driven in part by fears of military conscription. Serbia has become a preferred destination due to its visa-free regime and the generally pro-Russian sentiment among its population. Due to the influx of Russians, Turks, and also Ukrainians, Montenegro is the only WB6 country experiencing a slight population increase.

The governments’ reaction to the demographic crisis

The demographic crisis and pronatalist policies are increasingly evident in public debate across the WB6 countries. However, this rarely leads to the development of specific, comprehensive programmes. Government measures primarily focus on one-off financial incentives for parents, which, while helpful, fail to address the systemic population challenges. The reasons why people in the Western Balkans choose to emigrate or decide not to have children are increasingly linked to structural and cultural changes. However, local political elites are generally uninterested in raising democratic standards, tackling corruption, or improving the judicial system and public services. In fact, the emigration of disillusioned citizens seeking genuine change and comprehensive reform often benefits the region’s leaders, as it helps to consolidate their power.

Demographic issues are also becoming a more prominent topic among politicians, particularly in Serbia. The country has introduced substantial one-off birth grants, currently amounting to approximately €4,200 for the first child in the family and €5,000 for the second. Benefits for the third and fourth child are even higher but are paid in instalments. Ahead of the 2020 election, Aleksandar Vučić’s party campaigned under the slogan “Za našu decu” (For our children), which, according to the Serbian authorities, was meant to outline future priorities, including demographic policies. This issue has also been reflected in Serbia’s close ties with Hungary. President Vučić regularly participates in summits on the subject hosted by Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán and frequently highlights the issue of low birth rates. Belgrade has adopted several policies modelled on those implemented by Budapest, such as home purchase subsidies for parents who have a child. Depending on the region, these subsidies cover between 20% and 50% of the value of a home purchase or construction. However, due to numerous legal restrictions, only 583 Serbs have received these grants in the past two years.

Other, much smaller countries in the region offer lower financial incentives for parents. In BiH, which is experiencing the fastest depopulation, the amount of one-off financial support depends on the administrative entity in which the child is born. In Republika Srpska, parents receive approximately €250, while in the Federation of BiH, the amount is approximately €500. In 2019, the Albanian government introduced a one-off birth grant programme to support families and encourage higher birth rates. The benefit amounts to approximately €400 for the first child, €800 for the second, and €1,200 for the third and subsequent children. Initially, the programme covered all Albanian citizens, even those living abroad. However, in 2023, the eligibility criteria were changed, and now only parents who have resided in Albania for at least 180 days in the year preceding the child’s birth qualify for the payment. In North Macedonia, parents also receive a one-off birth grant: €80 for the first child, €320 for the second, and €960 for the third. In 2021, Kosovo introduced monthly child benefits, with the amount depending on the number of children in the family: €20 for one child, €40 for two, and €90 for three, paid until the child turns 16. Montenegro, the smallest country in the Western Balkans, recently increased its one-off birth grants. As of 2025, parents will receive €1,000 for their first child, €1,500 for the second, €2,000 for the third, and €2,500 for the fourth and subsequent children. Additionally, the government in Podgorica provides families with a monthly allowance of €30 per child until he or she reaches adulthood.

The potential of the diaspora

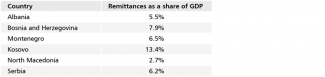

Another possible response to the ongoing demographic crisis could involve a shift in how WB6 governments engage with their large diasporas. Thus far, emigrants have largely been regarded as providers of remittances that help to offset the negative economic effects of mass emigration. These financial transfers from abroad constitute an important and stable source of income for many households, boosting consumption across the WB6 countries. In 2022, remittances accounted for between 2.7% of GDP in North Macedonia and as much as 13.4% in Kosovo.[18]

Table 3. Remittances sent by representatives of the WB6 diaspora to their countries of origin

Source: ‘Retaining the Growth Momentum’, Western Balkans Regular Economic Report, no. 26, autumn 2024, The World Bank, worldbank.org.

Experience gained by other countries, such as Ireland, has shown that a large diaspora can play a key role in promoting national interests abroad and facilitating the transfer of knowledge and skills, thereby helping to curb the trend of mass depopulation. Citizens living abroad often acquire new skills, professional experience, and networks of contacts, which can contribute to economic growth and innovation in their country of origin, even if they do not intend to return. Many become entrepreneurs, creating new jobs or facilitating the transfer of knowledge.[19]

Kosovo was among the first countries in the region to recognise the potential of its diaspora. In 2013, its government adopted a strategic document underscoring the diaspora’s importance in strengthening relations with countries where Kosovars reside. In the Kosovo National Strategy for 2022–2027, engaging emigrants in the country’s economic development was listed as one of the government’s top priorities. Similarly, in 2020, Tirana adopted the Albanian Diaspora National Strategy 2021–2025, aimed primarily at identifying people of Albanian origin and recognising their contribution to the country’s economic development.[20] Other Western Balkan states – Serbia, North Macedonia, Montenegro, and BiH – have also published similar documents. The core elements of these strategies include establishing contacts (especially business-related) with members of the diaspora and encouraging them to invest in their countries of origin.

However, cooperation between the diasporas and the WB6 governments faces significant challenges. These stem from the very reasons that originally prompted many citizens to leave: low confidence in public institutions, administrative inefficiency, political instability, and an unfavourable business environment.

The outlook is pessimistic

The demographic future of the region appears bleak. Persistently low fertility rates and mass emigration significantly reduce the likelihood of reversing these negative trends, while government efforts to boost birth rates remain fragmented and largely ineffective. As their populations shrink, the future development of WB6 economies is also at risk. Their competitive advantage to date has relied on the availability of cheap and highly skilled labour. Faced with growing labour shortages, the Western Balkan countries are now trying to offset these deficits through immigration.

Long-term forecasts predict a significant decline in the population of all countries in the region. According to the United Nations, the population of the Western Balkans will decrease by 3 million by 2050. Serbia, which recorded 6.7 million inhabitants in the most recent census, may have just 5.5 million by 2050 – a reduction of around 1.2 million, representing an 18% drop. North Macedonia, with a population of 1.83 million in 2024, is also expected to lose 18% of its population. The population of Montenegro, the smallest WB6 country, is projected to shrink by 15%.

The current demographic situation in BiH, Albania, and Kosovo is already worse than what the UN had projected. In the second half of the 21st century, BiH’s population is expected to fall from 3.1 million to 2.4 million, a 22% decrease. However, some demographers believe that the actual population may already be lower than the UN’s forecast for 2050. A similar pattern can be observed in Albania, where the 2023 population census recorded fewer residents than the UN estimates for 2035. In the case of Kosovo, the UN forecastsa population of 1.64 million by 2050, yet the 2023 census has already recorded only 1.58 million. The youngest country in Europe has, in fact, already dipped below the forecasted level.

Chart 5. Projection of change in WB6 population between 2024 and 2050

Source: UN.

[1] The largest ethnic group in BiH, the Bosniaks – who comprise just over 50% of the population – advocate for greater centralisation of the state. Meanwhile, the smallest group, the Croats (15%), demand changes to the method of electing members of the BiH Presidium. The political representation of the country’s three constituent nations operates under a strict system of ethnic quotas. Any proposals based on census results that alter the perceived balance of power could destabilise the country’s already fragile political stability.

[2] This refers specifically to the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, which consisted of Serbia and Montenegro. The state emerged from the break-up of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (SFRY) and existed from 1992 to 2003.

[3] ‘U.S. Committee for Refugees World Refugee Survey 1998 - Yugoslavia’, United States Committee for Refugees and Immigrants, 1 January 1998, refworld.org.

[4] Since then, for political reasons, the authorities in Sarajevo have not managed to carry out an official population census; as a result, the exact number of the state’s inhabitants remains unclear.

[5] ‘Demografi: U BiH živi 2,9 milijuna stanovnika, a prema nekim procjenama, manje i od 2 milijuna’, Večernji List, 23 November 2023, vecernji.ba.

[6] J. Vukićević, ‘Izazovi za Crnu Goru od priliva ruskih migranata’, Radio Slobodna Evropa, 7 April 2023, slobodnaevropa.org.

[7] ‘Current health expenditure (% of GDP) - Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Serbia, North Macedonia, Montenegro’, The World Bank, 15 April 2024, data.worldbank.org.

[8] ‘Labour Migration in the Western Balkans’, OECD, 16 May 2022, oecd.org.

[9] ‘International Migrant Stock 2024’, UN, un.org.

[10] ‘Westbalkanregelung’, Federal Employment Agency, arbeitsagentur.de.

[11] A comprehensive analysis of migration processes involving the WB6 states is hampered by the fact that local authorities do not maintain annual registers of their citizens’ places of residence. This text focuses on Germany, which is the most popular destination for the region’s residents and compiles detailed migration statistics.

[12] ‘Country capacity to retain talent, 1-7 (best)’, The World Bank, prosperitydata360.worldbank.org.

[13] A. Vračić, ‘Put za povratak: Odlazak obrazovanih ljudi i prosperitet na zapadnom Balkanu’, European Council on Foreign Relations, 11 July 2018, ecfr.eu.

[14] Figures for Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Montenegro, Serbia and North Macedonia are quoted after Statista; while figures for Kosovo after Trading Economics.

[15] ‘Unemployment statistics’, Eurostat, ec.europa.eu/eurostat.

[16] ‘Cost of Youth Emigration in the Western Balkans’, Westminster Foundation for Democracy, 24 October 2019, wfd.org.

[17] Мобилност радне снаге, Институт за развој и иновације, 2024, iri.rs.

[18] Retaining the Growth Momentum, Western Balkans Regular Economic Report, no. 26, autumn 2024, The World Bank, worldbank.org.

[19] Code for Albania, a project organised by the Albanian diaspora living in Silicon Valley, is one such initiative. It aims to promote the development of programming skills among Albanian youth.

[20] Strategjia Kombëtare e Diasporës Shqiptare 2021 - 2025, Agjencia Kombëtare e Diasporës, akd.gov.al.