Turning the tide: the US pushes back against Chinese influence in European ports

Over the past decade, Chinese investors have expanded their presence in European ports, acquiring significant stakes in some of the continent’s largest terminals, including those in Rotterdam, Hamburg, and Antwerp. Following the 2008 financial crisis, efforts to attract Chinese capital were motivated by the desire to boost trade flows. However, there are now growing concerns that China’s rising influence in the EU’s ports could deepen the bloc’s strategic dependence on Beijing. Amid escalating international tensions, ports have again been recognised as critical infrastructure, with special attention paid to the security of data flowing through them, including information related to NATO operations. This issue has gained particular urgency as the EU increasingly refers to China as a ‘systemic rival’, primarily due to its support for Russia. Furthermore, it remains unclear what role Chinese vessels played in two recent incidents involving damage to critical infrastructure in the Baltic Sea. Against this backdrop, the recent decision by Hong Kong-based CK Hutchison to sell 14 European terminals to the US-Swiss-Italian consortium BlackRock-TiL represents a setback for China’s strategy to expand its influence in the EU’s port and logistics sector. The sale, driven in part by pressure from the Donald Trump administration, also presents an opportunity to enhance Europe’s strategic autonomy in the area of critical infrastructure.

As the international order and global economy grow increasingly unstable, ports have been recognised not only as key nodes of critical infrastructure, including entry points for imported energy resources, but above all as gateways ensuring access to global trade and, in many cases, to the supplies of weapons and military equipment. The COVID-19 pandemic was the first major event to demonstrate that without adequate port capacity, it is difficult to respond effectively to various international shocks. The decoupling of economic cycles between different regions of the world, triggered by uneven waves of infection and the introduction of restrictions, disrupted supply chains and resulted in bottlenecks at major ports. This was followed by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, which forced rapid adjustments in energy supply chains across Europe,[1] primarily through the use of maritime transport. It also highlighted the severe consequences of port blockades for the Ukrainian economy. Taken together, these developments have heightened the importance of port security in the perception of many European countries. They have also led to closer scrutiny of the presence of external actors in the European port system, including China, which is seeking a dominant role in global shipping.

In this context, Donald Trump’s return to power in the United States is accelerating these processes rapidly. While his predecessor sought to gradually rebuild US influence in maritime trade and port infrastructure, the current president is applying considerably greater pressure on Chinese investors in the port sector. He is also pursuing a range of measures aimed at hampering cooperation between European shipping companies and China, as well as curbing Chinese influence in global shipping and the shipbuilding industry. One example of these efforts is the proposal for US ports to introduce additional fees for handling vessels either manufactured in China or owned by Chinese shipping companies;[2] this has already compelled European operators to adjust their route networks.

China’s expansion in European ports

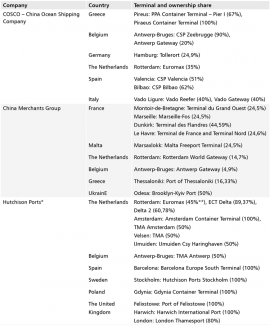

At present, Chinese logistics companies hold stakes in 33 maritime container terminals across Europe (see Table 1). It is important to note that, with the exception of the Greek port of Piraeus, which is fully controlled by China’s COSCO, Chinese entities control only individual terminals within European ports, while the port land and port authorities remain under local jurisdiction. However, the large number of these entities, combined with their systemic importance, gives them increasing influence over the functioning of the entire market as well as access to day-to-day operations and the information flows generated by ports. Chinese state-owned enterprises hold shares in 20 of these terminals: ten are owned by COSCO Shipping and nine by China Merchants Group (CMG). In addition, the Hong Kong-based private company Hutchison Ports,[3] holds stakes in 14 terminals.[4] Chinese entities are already active in Europe’s three largest ports. All three of the aforementioned companies have invested in terminals in Rotterdam; COSCO is also a co-owner of terminals in Antwerp and Hamburg. By comparison, in the United States, Chinese investors hold stakes in just four terminals.[5] Meanwhile, European investors have minority shareholdings in seven Chinese ports.

The process of Chinese companies acquiring stakes in European terminals has intensified over the past decade. Weakened and heavily indebted as a result of the global financial crisis of 2007–2009, and subsequently affected by the turbulence surrounding the Eurozone between 2010 and 2015, the European port sector began seeking ways to improve its financial position. Chinese investors moved to seize this opportunity. As early as 2008, COSCO leased two piers at the port of Piraeus, now one of Europe’s busiest container ports, where it constructed two terminals. In the years that followed, Greece experienced a debt crisis that threatened the integrity of the Eurozone. In exchange for financial assistance, the other members of the monetary union forced Greece to privatise key state-owned enterprises.[6] In 2016, COSCO acquired a 51% stake in the port authority from Greece’s privatisation fund for €280 million; in 2021, it took the unprecedented step to purchase a further 16% of shares. While it is standard practice in the port industry for private companies to operate terminals as part of commercial activity, it is highly unusual for control over the port authority itself to be transferred. Most countries are reluctant to relinquish their autonomy over strategic decisions concerning port development.

Another significant transaction was CMG’s acquisition of a 49% stake in Terminal Link in 2013. Until then, since its establishment in 2001, this company had been wholly owned by the French shipping firm CMA CGM. As a result of the transaction, CMG became co-owner of 15 terminals, including four in France, two each in Belgium and the United States, and one each in China and South Korea.[7] In 2019, as part of efforts to reduce its debt burden, CMA CGM signed an €815 million agreement to sell a further eight terminals to the joint venture, including those in the Netherlands (Rotterdam), Singapore, Ukraine (Odesa), and China.[8] In 2017, APM Terminals sold its 76% stake in CSP, the only deepwater terminal in Bruges, to COSCO. As a result, the Chinese company, which had held a minority share,[9] since 2014, gained full control over this terminal.

A major shift occurred only after Donald Trump returned to office as President of the United States. From his first days in office, he forcefully emphasised the need to eliminate Chinese influence in the Panama Canal, a critical route for US coastal shipping and maritime trade with Europe and Asia. In this increasingly challenging political context, in early March the CK Hutchison holding company announced its intention to sell two terminals located on either side of the canal to the Italian-Swiss consortium TiL (owned by MSC, the world’s largest shipping company) and the US investment fund BlackRock. Furthermore, as part of the same transaction, Hutchison also decided to divest its entire port portfolio outside China, comprising 14 terminals in Europe, including one in Gdynia, Poland. Hutchison had long struggled to expand its port operations and had explored divestment options, but until recently, the only potential buyers were the two other global port operators from China. It should be noted, however, that the transaction is still subject to regulatory approval in a number of countries, so finalising it may take up to a year. The involvement of US financial institutions in this deal is particularly surprising, as they have largely avoided the port sector in recent years, treating this sector as standard business infrastructure that offered insufficient returns.

An ambiguous balance of benefits from attracting Chinese investment

The EU’s previous openness to the expansion of Chinese investors in its ports stemmed, on the one hand, from the deteriorating financial condition of its terminal operators and the desire to secure new investments funds, and, on the other hand, from intensifying competition between them to attract cargo flows from China. The results of this policy have been mixed. For instance, the decision to allow COSCO to acquire a stake in the CSP terminal in Bruges was driven by the desire to gain new competitive advantages. At that time, the port was struggling with challenges stemming from the consolidation of the logistics sector in the aftermath of the global financial crisis and losing ground to stronger competitors in the North Sea region.[10] The terminal quickly increased its throughput – from 316,000 TEU in 2017 to 1.2 million TEU in 2023.[11] The facility’s new Chinese owners invested in new equipment; moreover, two of the seven shipping services operated by the Ocean Alliance, of which COSCO is a member, were redirected to the terminal. The pandemic also played a role, causing congestion at Europe’s largest ports and prompting greater use of smaller terminals. However, despite the port’s improved performance, the Belgian economy derived only limited benefits from further Chinese involvement in Bruges. At the same time, concerns emerged over the crowding out of local service providers operating within the port.[12]

Piraeus presents a comparable case. Owing to Chinese investment in new port equipment, container throughput increased sharply between 2017 and 2019 – from 3.7 million TEU to 5.2 million TEU.[13] The port also benefited from substantial investment. However, the subsequent years proved significantly more challenging: throughput fell to 4.3 million TEU in 2022, with a reversal of this trend only occurring last year, when volumes rose to 4.6 million TEU. This growth was driven primarily by transshipment operations (the transfer of cargo from larger vessels to smaller ones, or vice versa), which generated relatively low added value for the Greek economy.[14] In addition, Chinese firms began taking over port services that local companies had previously provided. At present, the development prospects of Piraeus are also increasingly uncertain due to the ongoing instability in the Red Sea, a development that has raised questions about the continued viability of transport through the Suez Canal. Larger shipping operators, in particular, have been forced to take the route around Africa, diminishing the port’s advantage as the first European transshipment hub on the Asia–Europe route. Nonetheless, the overall period of Chinese investment in Piraeus should be viewed positively. In 2007, the port ranked only 16th in Europe in terms of container throughput with 1.7 million TEU;[15] by 2023, it had risen to fourth place, reaching 5.1 million TEU.

Chinese involvement in European ports should not be viewed solely through a commercial lens. This conclusion is illustrated by the case of Rotterdam, Europe’s largest port, where Chinese companies have maintained a presence for years and currently control four of the 14 container terminals. According to Dutch analysts,[16] the involvement of Chinese businesses is an asset in the competition to attract transshipment volumes, which could, in the long term, help draw Chinese trade and logistics companies to Rotterdam. However, they also highlight the risks associated with an excessive influence of Chinese entities in the EU’s logistics and processing sectors, as this creates opportunities for them to increasingly play European terminals off against one another.

In the Netherlands, there are growing concerns that China’s rising economic position in the country could heighten tensions between efforts to maintain its status as a maritime logistics hub and the need to preserve strategic decision-making autonomy. This could become a source of significant friction within the EU, particularly between the Netherlands and member states that are less economically dependent on China, especially with regard to security interests. The Netherlands is also wary of growing pressure from the United States to curb Chinese influence in the logistics sector due to potential security risks, including espionage, sabotage, and cyberattacks. In this context, Dutch analysts do not recommend halting cooperation with China, but rather advocate for improved risk management – a position that aligns with Germany’s emphasis on de-risking. The key elements of this approach should include outlining strategic framework for cooperation, pushing for a level playing field in market access, reforming the EU’s competition law, and strengthening the capacity to control digital processes in ports.

An uneven playing field?

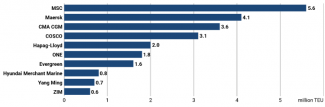

European ports are becoming increasingly important for Chinese investors, both as gateways for the expansion of Chinese goods in the EU market and as key hubs for their broader operations. The total value of COSCO’s and CMG’s investments in Europe is estimated at €9 billion. In 2023, European terminals accounted for 51% of the revenues of COSCO Shipping Ports, the subsidiary managing COSCO’s global terminal network, compared to just 32% in 2016.[17] Given the rising importance of European ports for the performance of Chinese companies and the large number of terminals in which they hold shares, the argument for involving Chinese capital to attract cargo flows to individual terminals is losing relevance. While, a few years ago, Chinese investment may have been regarded as an important asset, today, with Chinese companies holding shares in several key, and often competing, terminals (for instance, COSCO owns shares in Antwerp, Hamburg and Rotterdam), they are increasingly in a position to play these terminals off against one another in order to reduce the costs of using them. Their bargaining power is further strengthened by the fact that COSCO, in particular, is not only a port operator but primarily a major provider of maritime transport and freight forwarding services, challenging Europe’s leading shipping lines. It is currently the world’s fourth-largest shipping company after the Italian-Swiss MSC, Denmark’s Maersk and France’s CMA CGM. With such market strength, it is able to direct cargo flows towards preferred locations. Moreover, both COSCO and Hutchison Ports are increasingly offering intermodal services in the EU market, which may, over time, become an expanding source of their competitive advantage.

Chart 1. Combined transport capacity of the fleets of the 10 largest container shipping lines

Source: Z. Ahmed, ‘Top 20 Largest Container Shipping Companies In The World’, Marine Insight, 14 February 2025, marineinsight.com.

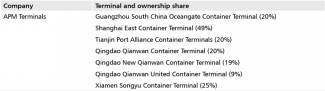

Ports are no exception in EU–China economic relations, which are generally characterised by an imbalance in market access in Beijing’s favour. While three Chinese companies, including two state-owned enterprises, hold stakes in 33 European terminals, only a single European private company, APM Terminals controlled by Denmark’s Maersk, holds shares in seven comparable facilities in China (see Appendix).

Chinese companies are usually involved in European terminals as minority shareholders. State-owned entities hold majority stakes only in a few cases: in Antwerp–Bruges, Piraeus, and Valencia. As previously mentioned, Piraeus is a notable exception, as COSCO exercises full control over both of its terminals and the port authority itself. The position of the private company Hutchison Ports is different: it usually holds majority shares in European terminals or is their sole owner. Under company law in the EU’s member states, holding as little as 25% of shares is sufficient to block key corporate decisions. By contrast, among European investors, only APM Terminals has acquired stakes in six terminals in China, none of which exceed 25%, with the exception of a 49% stake in Shanghai East Container Terminal.

China’s efforts to build competitive advantages

A situation in which Chinese entities not only control almost all ports in China but also exert growing influence in Europe may, in the long term, become an effective lever for shaping trade flows. This opens a pathway to profits not only from exports, but also from transport and logistics services. Additionally, it could create a potentially invaluable source of informational advantage. Nonetheless, at least in the medium term, European shipping lines will likely be able to offset these advantages through their own market strength.

In the future, Chinese companies’ stakes in inland transshipment terminals, including intermodal facilities, may give them a decisive edge, enabling control over the entire logistics chain deep into the European continent. Thus far, Hutchison Ports has had a presence in inland terminals in the Netherlands (Willebroek, Venlo, Amsterdam, and Moerdijk) and Germany (Duisburg), while COSCO owns intermodal terminals in Madrid (Conterail) and Zaragoza (Noatum Rail Terminal Zaragoza). China could potentially seek to use its influence in European ports to push the interests of its companies within European logistics chains and gradually displace other firms in the process.[18] Similar patterns have already been seen in other sectors; these include the expansion of Chinese control over supply chains for photovoltaic panels and electric vehicles, restrictions on the sale of rare earth materials, and limitations on drone exports to third countries.

As China’s economic power continues to grow, the EU is increasingly concerned over the risk that Beijing could leverage its influence in the European logistics sector to support exports to the continent through non-market means. The European Parliament has noted China’s growing interest in acquiring parts of the EU’s critical infrastructure, such as ports, since the launch of its Belt and Road Initiative in 2013.[19] European companies are unlikely to be able to compete with their Chinese rivals, who benefit from substantial non-transparent state support, particularly in the context of increasingly restricted access to the Chinese market that creates an uneven playing field. Both private and state-owned companies from China are heavily subsidised domestically,[20] as was the case with COSCO in 2017.[21]

Ports under the control of a systemic rival?

Over the past decade, the EU has gradually redefined its relationship with China. The 2019 EU Strategic Outlook described Beijing as a partner, a competitor, and a systemic rival. In the years that followed, these designations have been given concrete meaning through numerous anti-subsidy and anti-dumping investigations, as well as the development of the EU’s economic security strategy. China’s image within the EU has been seriously damaged by its increasingly close ties with Russia, and by the diplomatic and industrial support it has provided to Moscow since 2022. EU diplomacy, in particular, now increasingly refers to China explicitly as a systemic rival.[22] Brussels has also begun adopting legislation focused on monitoring inbound investment and protecting critical infrastructure.

These trends have also shaped the EU’s evolving approach to critical infrastructure. In 2022, it adopted the Directive on Critical Entities that requires member states to audit such infrastructure and enhance its resilience.[23] However, actions at the national level regarding ports have been far less consistent. On the one hand, countries such as Croatia, Lithuania, and Italy have rejected Chinese bids to acquire shares in the ports of Rijeka,[24] Klaipėda, and Trieste, respectively. On the other hand, the German government, aware of stagnant throughput in Hamburg and the port’s declining position relative to its competitors in Antwerp and Rotterdam, approved the sale of a 24.99% stake in the Tollerort terminal,[25] a level below the threshold required to exert influence over its operations. The decision to reduce the originally proposed stake was prompted by opposition from the ministries of economy, foreign affairs, interior, finance, and defence, all of which had opposed the transaction. They expressed concerns that granting Chinese companies control over one third of the terminal, as initially proposed, could give China additional leverage over Germany, particularly given its status as Hamburg’s most important trade partner.[26] The European Commission also signalled a negative stance on this transaction, highlighting the potential for leaks of sensitive information related to port operations, especially the transport of military equipment.[27]

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and China’s unofficial support for Russia have only heightened concerns about the security of the EU’s ports in the context of the supply of raw materials and military equipment, particularly given that Chinese investors are present in terminals located near military ports, such as those in Amsterdam, Antwerp–Bruges, Gdynia, Le Havre, Rotterdam, Stockholm, and Valencia.[28] In the event of a crisis or conflict, China could potentially use this presence to monitor the transport of NATO troops and equipment, or even engage in acts of sabotage aimed at hindering the movement of forces from North America and the United Kingdom to Central Europe. The North Sea ports in Belgium, the Netherlands, and Germany play a key role in military mobility and the implementation of NATO’s defence plans for its eastern flank. Enhancing port and maritime surveillance, as well as the protection of ports and maritime areas, forms part of the Permanent Structured Cooperation (PESCO) framework, under the Italy-led HARMSPRO project, which involves Poland, Greece, and Portugal.

China’s credibility in the field of maritime logistics has also been undermined by incidents involving critical infrastructure in the Baltic Sea. Chinese vessels are suspected of damaging the Estonian–Finnish Balticconnector gas pipeline in October 2023,[29] and subsea telecommunications cables linking Sweden with Lithuania and Finland with Germany in November 2024.

China and the cybersecurity of ports

While increasing its capital engagement in European ports, China has also actively promoted its own digital solutions. One such solution is the National Transportation and Logistics Public Information Platform (LOGINK), a port traffic management system developed in 2007 in one of China’s provinces, which is now increasingly used worldwide. Initially adopted in Asian countries, it later spread to Europe. LOGINK currently has cooperation agreements with 24 ports worldwide, including seven in Europe (Antwerp, Barcelona, Bremen, Hamburg, Sines, Riga, and Rotterdam). In China, it aggregates data from five million trucks, 200 warehouses, and 450,000 users, making it a key tool for managing flows in China’s foreign trade.[30]

LOGINK is not an independent platform, as it is formally overseen by China’s Ministry of Transport. Furthermore, the Chinese government has promoted this system by ensuring free access to it. In the United States, concerns about the implications of using LOGINK have led the government to ban the Pentagon from using ports that operate this platform.[31] Meanwhile, the Netherlands has promoted an alternative system within the EU called the Basic Data Infrastructure.[32]

Concerns about the reliability of Chinese software are not unfounded. For instance, in 2023, Belgian intelligence services accused CaiNiao, a logistics company owned by the Chinese e-commerce giant Alibaba Group, of conducting espionage via specialised software installed at Liège airport, one of the EU’s key hubs for air cargo.[33] The company defended itself by stating that although the data was processed via the Alibaba Cloud platform, it was stored on servers located in Germany. If Chinese systems were to become widespread in the logistics sector, there would be a risk that the data collected could be used to provide Chinese entities with an unfair competitive advantage. In the event of a crisis in EU-China relations, this data could potentially be manipulated to disrupt logistics operations.[34]

China’s expansion in European ports has also raised concerns about the potential for increased activity by Chinese criminal organisations in Europe, particularly with regard to smuggling and the import of counterfeit goods or those that do not meet the EU’s safety standards. This may also hinder international cooperation between law enforcement agencies in combating port-related crime, such as drug trafficking. For example, the Port of Piraeus was excluded from the European Ports Alliance to fight drug trafficking that the European Commission and the Belgian Presidency of the Council of the EU launched in January 2024.[35]

The United States places particular emphasis on port security due to concerns that China could use port monitoring to gather extensive information about various sectors of the economy and the activities of other countries. In recent months, there has been growing debate over the risks associated with the use of cranes in US ports, 80% of which originate from China.[36] This situation has given rise to concerns about industrial and military espionage: in 2022, the US Department of State levelled such allegations against the Chinese crane manufacturer Shanghai Zhenhua Heavy Industries (ZPMC). The US port industry has also warned that the latest models of such equipment collect vast quantities of data that could be exploited for intelligence purposes. The Port of Los Angeles, which established a Cybersecurity Operations Center in 2014, currently records as many as 63 million such attacks each month.[37]

Excessive dependence on Chinese-manufactured equipment in ports also poses risks to resilience, due to the high likelihood of disruptions in the supply of spare parts in the event of heightened political tensions. In November 2023, the US administration established the Supply Chain Resilience Center whose tasks include assessing risks related to port infrastructure. In February 2024, President Joe Biden issued executive orders to strengthen cybersecurity oversight in US ports through measures such as tighter enforcement of international security regulations, stricter reporting of cyberattacks, and the creation of a maritime security director.[38] In January this year, the United States placed COSCO on a blacklist of entities cooperating with the Chinese defence sector, thereby advising US companies against engaging in business with this operator. According to media reports, this move prompted the Greek government to assess the implications of Washington’s decision for the Port of Piraeus.[39]

Conclusions

Since the initial attempts to recalibrate EU–China relations in 2018–2019, through the introduction of a mechanism for screening Chinese investments, the EU’s agenda to reduce risks in its interactions with China has expanded considerably. Nevertheless, the imbalances in economic relations have continued to deepen, to Europe’s disadvantage. As China’s economic power grows, Beijing is increasingly taking advantage of the EU’s asymmetrically open economy, while effective instruments to counter these unfavourable trends have yet to be developed. The port sector provides a clear example of this dynamic. Over the past decade, Chinese companies have expanded rapidly in this field, establishing strong footholds in key European ports, while the influence of EU investors in China has steadily declined. At the same time, the current, considerably less stable international environment highlights the need for closer monitoring and enhanced protection of critical infrastructure. In this context, the role of ports should no longer be viewed solely through a commercial lens.

The EU should be particularly concerned about the support that China has provided to Russia. This undermines trust in Chinese investors, who, as co-owners of major European terminals, may gain access to data that is sensitive both commercially and militarily. In light of the rapidly deepening de facto alliance between China and Russia, there is a genuine risk that such information could be transferred to the Russian side. Control over terminals already makes it possible to monitor goods passing through them and observe nearby facilities. As the digitalisation of port infrastructure advances, it will also enable access to the data collected by ports. In this context, further EU-level cooperation is needed to clarify the meaning of the term ‘systemic rival’ and define the EU’s overall approach to China and the scope of cooperation with it.

Another growing concern is China’s tightening control over its economy, a trend that increasingly compels even private Chinese companies to align with the government’s priorities. It is evident that the activities of Chinese companies, including those privately-owned, will be increasingly coordinated by the government. This challenge is all the more serious given that China possesses considerable leverage over the EU’s ports and is able to play them off against one another due to its ability to direct a significant share of trade flows between Europe and China. Beijing has also applied similar practices in other sectors, turning them into a challenge for the EU’s competition law. This must take into account the fact that all Chinese entities may be subject to control by a single actor, effectively operating as one giant holding, and may exploit mutual linkages to support their expansion across the European continent.

Therefore, European solutions for digitalising port services should be developed with a dual focus on security and ensuring a level playing field in competition. Data security research centres that analyse information processed by Chinese-manufactured port equipment also play an important role. Without such efforts, the EU risks rapidly losing control of data aggregated by ports along with its ability to safeguard digital security.

Paradoxically, the policies of the Donald Trump administration have created an opportunity to at least partially restore the EU’s strategic autonomy in the port sector. It has enabled European shipping companies, supported by US investment funds, to regain some of their influence in ports across the European continent. The EU has been developing its economic security toolkit for several years. The concept of open strategic autonomy is designed to restore the EU’s ability to act independently and achieve self-sufficiency in key areas. However, effective instruments to implement this policy have so far been lacking. US pressure has now created favourable conditions for European companies to reclaim certain sectors from China and rebuild some of their capabilities linked to maritime trade. This opportunity has been seized by the Italian–Swiss company MSC which, with backing from the US-based firm BlackRock, is now well positioned to acquire significant stakes in 14 European terminals, most of which are currently under the full control of China-linked investors.

Moreover, actions taken by the United States in recent years suggest that it will press on with efforts to recover its influence in maritime shipping and ports. While this may pose certain challenges for the EU, it will also generate new opportunities for cooperation. The US is becoming increasingly aware that control over maritime routes is a key asset for China in expanding its global influence, with ports playing a central role in this strategy. The US is likely to place growing emphasis on the security dimension of this issue, expecting Europe to provide greater protection for the movement of NATO forces, a demand that could serve as a pretext for increased pressure to reduce the involvement of Chinese investors in European ports. In the longer term, the US may also use concerns regarding the security of data processed in European ports as justification for restricting the use of Chinese-manufactured equipment, for example, by redirecting cargo flows to terminals in which US companies hold stakes.

ANNEX

* ‘2023 Annual Report. Operations Review – Additional Information’, CK Hutchison Holdings Limited, at: irasia.com.

** ‘Evergreen Purchases 20% Equity Of Rotterdam Port One Terminal’, SDI Logistics, 18 August 2023, sdilogistics-shippings.com.

Source: the author’s own compilation based on industry data.

Table 2. European investors’ shares in Chinese ports

Source: the author’s own compilation based on industry data.

[1] For example, between 2021 and 2023, oil transshipments at Naftoport in Gdańsk nearly doubled, surging from 17.9 million tonnes to 36.6 million tonnes. Poland would also not have been able to end its dependence on coal supplies from Russia had there not been a sharp increase in coal transshipments in 2022 – these soared by 127% to 20.9 million tonnes. Polish ports also continue to play a key role in delivering military equipment to Ukraine.

[2] L.A. LaRocco, ‘Trump is targeting China-made containerships in new flank of global economic war on the oceans’, CNBC, 11 March 2025, cnbc.com.

[3] While COSCO and CMG are centrally managed state-owned enterprises, Hutchison Ports is part of the Hong Kong-based global conglomerate CK Hutchison Holdings owned by the billionaire Li Ka-shing who holds a controlling stake of 30.36%. Due to Beijing’s consolidation of control over Hong Kong and the extensive business operations of Li and his family in China, he remains under the influence of the Chinese government.

[4] Both Hutchison Ports and COSCO hold shares in the same terminal, Euromax in Rotterdam, which explains why the total number of partial stakes in terminals differs from the number of terminals with Chinese ownership.

[5] COSCO holds shares in two terminals, the West Basin Container Terminal China Shipping in Los Angeles and SSA Marine in Seattle, similarly to CMG, which holds shares in Terminal Link Texas in Houston and the South Florida Container Terminal in Miami.

[6] H. Wetzels, ‘Chinese takeover of European seaports’, Follow the Money, 16 July 2024, ftm.eu.

[7] ‘CMHI and CMA CGM complete the Terminal Link Transaction’, CMA CGM & CMHI Press Release, 11 June 2013, cma-cgm.com.

[8] ‘CMA CGM completes a first transaction relating to the sale of eight port terminals to Terminal Link for USD 815 million in cash’, CMA CGM, 26 March 2020, cma-cgm.com.

[9] ‘APM Terminals Zeebrugge completes share sale’, APM Terminals, 30 November 2017, apmterminals.com.

[10] N. Hakirevic Prevljak, ‘COSCO Shipping Ports, Zeebrugge Port extend container terminal concession’, Offshore Energy, 31 January 2022, offshore-energy.biz.

[11] The author’s own calculations based on COSCO reports.

[12] COSCO in the port of Zeebrugge, European Network of Corporate Observatories, 2024, p. 4, corpwatchers.eu.

[13] The author’s own calculations based on COSCO reports.

[14] Interviews with representatives of the industry and academic institutions conducted in March 2024.

[15] ESPO Annual Report 2007–2008, European Sea Ports Organisation, espo.be.

[16] B. Kuipers et al., Navigating an uncertain future. An exploration of China’s influence on the Netherlands’ future maritime logistics hub function, Clingendael Report, October 2022, clingendael.org.

[17] 2023 FY Results Announcement, COSCO Shipping Ports Limited, March 2024, ports.coscoshipping.com.

[18] Navigating an uncertain future…, op. cit.

[19] K. Smit Jacobs, ‘Chinese strategic interests in European ports’, European Parliamentary Research Service, February 2023, europarl.europa.eu.

[20] J. Lee, ‘Beyond China, Inc: understanding Chinese companies’, The Transnational Institute, 16 January 2020, longreads.tni.org.

[21] C. Dupin, ‘COSCO to receive massive $26b loan from China Development Bank’, FreightWaves, 12 January 2017, freightwaves.com.

[22] ‘Hearing of High Representative/Vice President-designate Kaja Kallas’, The European Parliament, 12 November 2024, europarl.europa.eu.

[23] ‘Making critical entities more resilient’, EUR-Lex, 19 February 2024, eur-lex.europa.eu.

[24] M. Seroka, ‘Budowa nowego terminalu głębokowodnego w Rijece’, OSW, 1 December 2021, osw.waw.pl.

[25] S. Płóciennik, ‘Sprzedaż udziałów w terminalu w Hamburgu: Scholz nie chce sporu z Chinami’, OSW, 25 October 2022, osw.waw.pl.

[26] ‘Hamburger Hafen: Kanzleramt will China-Geschäft offenbar durchsetzen’, Norddeutscher Rundfunk, 20 October 2022, at: archive.ph.

[27] M. Koch, J. Olk, ‘EU warnte schon im Frühjahr vor Einstieg der Chinesen in den Hamburger Hafen‘, Handelsblatt, 21 October 2022, handelsblatt.com.

[28] ‘Chinese strategic interests in European ports’, op. cit.

[29] J. Hyndle-Hussein, J. Tarociński, ‘The Balticconnector gas pipeline damage’, OSW, 11 October 2023, osw.waw.pl.

[30] T. Corradi, ‘China’s LOGINK: Securing Maritime Data in European Ports’, China Observers in Central and Eastern Europe, 22 February 2024, chinaobservers.eu.

[31] J. Stone, ‘US Bans Pentagon From Using Chinese Port Logistics Platform’, Voice of America, 21 December 2023, voanews.com.

[32] ‘Basic Data Infrastructure’, The Ministry of Infrastructure and Water Management of the Netherlands, 29 June 2022, topsectorlogistiek.nl.

[33] L. Dubois, Q. Liu, ‘Alibaba accused of ‘possible espionage’ at European hub’, Financial Times, 5 October 2023, ft.com.

[35] P. Haeck, ‘EU’s drug-busting ports alliance excludes Chinese-owned Piraeus’, Politico, 30 January 2024, politico.eu.

[36] L.A. LaRocco, ‘Biden administration warns Congress about China’s major presence at critical US ports’, CNBC, 29 February 2024, cnbc.com.

[37] Ibidem.

[38] Idem, ‘Biden to sign executive order on US port cybersecurity targeting Chinese-manufactured shipping cranes’, CNBC, 21 Febraury 2024, cnbc.com.

[39] S. Schlüter Jacobsen, ‘Greece is investigating potential impact from COSCO on US blacklist’, ShippingWatch, 13 January 2025, shippingwatch.com.