Czech demography: once a model, now a cause for concern

Until a few years ago, the Czech Republic stood out in the region for its relatively high fertility rate and was often cited – including in Poland – as a model of successful demographic policy. Today, however, Czechs themselves are increasingly raising the alarm, pointing to a series of negative records – such as the lowest birth rate since records began. If current unfavourable demographic trends persist and there is no increase in immigration, the country could face serious challenges, particularly in the labour market, which has already been struggling with a worker shortage for about a decade.

In Czech public debate, demographic issues are gradually joining the list of key development challenges, alongside overcoming the middle-income trap, addressing infrastructure concerns and determining the future of the automotive sector. Prague is likely to continue its relatively open approach to immigration – particularly from culturally similar countries – and will seek to integrate the large number of Ukrainian refugees into the labour market. At the same time, a broader debate is only just beginning on how to improve fertility rates through measures that go beyond those previously implemented and regarded as examples worth emulating.

Czech demography – (once) an example to follow

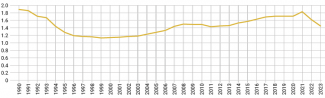

Just two years ago, the Czech Republic was frequently cited in Polish public debate as a model of successful demographic policy.[1] The peak of this relative success came in 2021, when the total fertility rate (TFR) – which reflects the average number of children a woman would have over her lifetime, assuming the birth rates of a given year – reached 1.83 (see Chart 2). This was the second-highest rate in the European Union, behind only France, and significantly higher than Poland’s rate at the time, which stood at 1.33. However, within two years, the Czech TFR dropped to 1.45, bringing it closer to the EU average of 1.38 (according to preliminary data); while Poland’s rate in that period fell to 1.16.

Despite certain cracks in the Czech demographic success story, some of the country’s financial and regulatory measures, along with selected cultural factors, may still be seen as conducive to family formation. Families benefit from a healthcare system ranked among the best in the region, according to international comparisons. This provides pregnant women and parents with a sense of security, making the decision to have children easier.[2] Among the Visegrád countries, the Czech Republic ranks highest in terms of ‘quality of life’ (OECD),[3] and ‘human development’ (UNDP).[4]

The Czech Republic is placed fourth among the 38 OECD member states – behind Greece, the United Kingdom, and Slovakia – in terms of the duration of at least partially paid maternity leave.[5] For a single child, standard maternity leave (mateřská dovolená) lasts 28 weeks (compared with 20 weeks in Poland), during which time a benefit (peněžitá pomoc v mateřství, or PPM) is paid, typically amounting to 70% of the mother’s average gross salary over the preceding 12 months (in Poland, the benefit is set at 100%).

This is followed by parental leave (rodičovská dovolená), during which the employer is not allowed to dismiss the employee. In the Czech Republic, parental leave can last until the child turns three, whereas in Poland it is limited to 41 weeks, covering – together with maternity leave – approximately the first 14 months of the child’s life. During parental leave, a benefit (rodičovský příspěvek) of CZK 350,000 (approximately €14,000) is provided, with a monthly ceiling of CZK 11,290 (around €447).[6] In the case of multiple births, the total benefit is higher. If the leave is shortened, the total amount is reduced proportionally. While employment is heavily restricted during the period in which the maternity benefit is received, parents on paid parental leave face fewer limitations and may take up work without forfeiting entitlement to the parental benefit. A key condition is the provision of adequate full-day childcare. This can be met either through alternating care between the parents (who can take turns claiming the benefit), placing the child in a nursery or kindergarten (for up to 46 hours per month), or arranging care by another adult.

In addition to maternity and parental benefits, the Czech Republic also provides a child allowance. However, its value differs significantly from Poland’s child-raising benefit. It is means-tested and varies depending on the child’s age, increasing as the child grows. The maximum monthly payment is CZK 1,580 (approximately €63), which is considerably lower than the PLN 800 (approximately €188) provided in Poland. Nonetheless, unlike in Poland, the Czech child allowance can be paid after a child reaches adulthood, up to the age of 26, provided they remain in full-time education. Altogether, the Czech Republic allocates 2.1% of its GDP to family benefits, which aligns with the OECD average. This is more than Slovakia (1.8%) but less than Hungary (2.4%) and Poland (3%).[7] When tax relief for families is included – which account for an additional 0.03% of GDP in the Czech Republic – the country falls below the OECD average of 2.3%, recording the lowest level among the Visegrád Four.[8]

Beyond financial and regulatory factors, cultural attitudes may also influence openness to parenthood, though they are difficult to quantify precisely. One indicator of traditional views is a recent Eurobarometer survey, which asked respondents whether they agreed that ‘a woman’s primary role is to take care of her home and family.’ In the Czech Republic, 67% of respondents agreed – a figure that, while 10 percentage points lower than seven years earlier, was still the fifth-highest in the EU and 29 points above the EU average.[9] The Czech Republic also stands out in terms of the proportion of children under the age of three cared for exclusively by their parents. This share is 68%, ranking fifth in the EU (in Poland it is 57%, placing it tenth).[10] This may suggest that, for many Czechs, time spent with young children holds greater value than professional advancement.

One factor that may have contributed to the Czech Republic’s better demographic performance compared with the entire region is the downward trend in the number of abortions. This decline has been recorded in absolute terms since 1989 and relative to the number of live births since 1990. Both the absolute number of abortions in 2023 (15,000) and the ratio of abortions to live births were the lowest since the 1950s, with comparable statistics dating back to 1953. When compared with the peak levels recorded in the late 1980s, the 2023 figures represent a 7.5-fold decrease in absolute terms and more than a fivefold decrease in relative terms.

This trend reflects not only the growing perception of abortion as a measure of last resort, but also the wide availability of various forms of contraception. However, recent years have seen a marked shift away from hormonal contraception, which is generally more effective in preventing pregnancy than alternative methods.[11] Between 2008 and 2022, the share of women aged 18–35 using hormonal contraception fell from 62% to 32%. According to local experts, this drop is primarily due to greater awareness of the potential side effects associated with hormonal contraceptives.[12]

If everything looks so good, why is it getting worse?

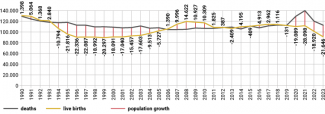

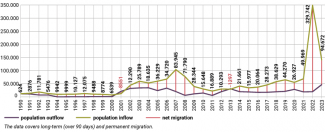

Despite strong demographic performance compared with the wider region, demographic indicators for the Czech Republic are deteriorating, and in the long term, only a consistently positive net migration rate will ensure population stability. Even in 2021, when the fertility rate reached its highest level in 30 years (1.83), it remained below the generation replacement rate of 2.1. At the same time, since 2019 (inclusive), the country has recorded more deaths than births. This natural population decline became particularly pronounced from 2020 onwards. Initially, in 2020–2021, the key factor deepening the demographic deficit was a sharp rise in the number of deaths linked to the COVID-19 pandemic. In the following two years, however, the main driver was a significantly lower number of births compared with previous periods, corresponding to a rapid drop in the fertility rate (see Charts 1 and 2).

Chart 1. Key demographic indicators in the Czech Republic, 1990–2023

Source: the author’s own estimates based on data from the Czech Statistical Office.

Chart 2. Fertility rate in the Czech Republic, 1990–2023

Source: the author’s own estimates based on data from the Czech Statistical Office.

The birth rate decline may be linked to a fall in living standards – in each quarter of 2022 and 2023, real wages decreased year-on-year.[13] At the same time, Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine undermined the sense of security, which plays a key role in decisions about parenthood. While in 2021 only 11% of Czechs expressed concern about the threat of war, by 2023 this figure had risen to 43%.[14] Similarly, in 2018, 40% of respondents considered the situation in Ukraine a threat to the security of the Czech Republic, compared with 64–75% between 2022 and 2024.[15] The Czech Republic has also followed the broader European trend of declining fertility rates, which fell in nearly all EU member states in 2022 and even more sharply in 2023.[16]

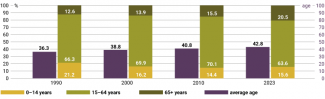

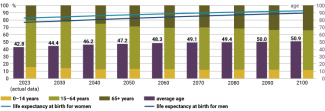

The steadily decreasing number of live births, combined with rising life expectancy[17] and limited immigration of younger people, is contributing to an ageing population. This is reflected in the growing share of elderly people (aged 65 and over) and the declining proportion of children aged 14 and under (see Chart 3). Between 1990 and 2023, the share of elderly people in the total population increased by nearly 8 percentage points, reaching over 20%, while the shares of children and working-age adults fell by 5.6 and 2.7 percentage points respectively, to just under 16% and 64%. In 2023, the average age of a Czech resident was 6.5 years higher than at the beginning of the post-communist transition.

The economic dependency ratio, which reflects the share of people aged under 20 and over 64 relative to the working-age population (20–64), currently stands at around 72–73% – similar to the level recorded in 1990, but for entirely different reasons. Back then, the ratio was high due to a large number of children. As that generation entered the labour market, the ratio declined, reaching a low of 55% in 2007. Today, however, the figure is driven primarily by the rising share of older people. While the Czech Statistical Office focuses on the combined dependency of both children and the elderly in relation to the total population, Eurostat highlights the old-age dependency ratio specifically. In 2023, the Czech Republic recorded an old-age dependency ratio of 32.1%, still below the EU average of 33.4%, but the highest among the Visegrád countries.[18]

Chart 3. Changes in the age structure of Czech society, 1990–2023

Source: the author’s own estimates based on data from the Czech Statistical Office.

One factor that does not support higher fertility is the breakdown of the traditional family model, which in many cases provided a degree of stability that made the decision to have children easier. In 2023, the number of marriages in the Czech Republic was nearly half of what it was in 1990, despite the population having increased by 5% over the same period. An increasing share of children are born outside marriage: in 1990, they accounted for just 8.5% of all births, rising to 22% by 2000, and reaching 47% in 2023. Cultural shifts have led to delays in decisions both to marry and to have children. While in 1990, women typically entered their first marriage just after turning 21, and men at the age of 24, by 2023 these averages had risen to 31 and 33 respectively. In the same period, the average age at which women have their first child rose from just over 22 to nearly 29.[19]

Delaying parenthood increases the likelihood of fertility problems – it is estimated that around one in five couples in the Czech Republic experiences difficulty conceiving. The scale of this issue is partially mitigated by the widespread use of in vitro fertilisation (IVF). Approximately 5% of children in the Czech Republic are born through assisted reproduction, a share that has doubled over the past 15 years.[20] However, IVF is relatively expensive, subject to specific legal restrictions and not pursued by some individuals due to moral or ethical concerns.

The abuse associated with egg donation, which prompted the Czech government to adopt a draft amendment to the relevant legislation in November 2024,[21] has been widely discussed in recent years. In the Czech Republic, women can undergo IVF treatment up to the age of 49, but only those under 40 are eligible for reimbursement from the national health insurance system. The cost of a single cycle of assisted reproduction without reimbursement is approximately CZK 85,000 (€3,365), while with reimbursement the cost is reduced to around CZK 35,000 (€1,385). Reimbursed procedures are limited to a maximum of four cycles.[22] A notable detail is that one third of the Czech assisted reproduction market is controlled by FutureLife, a holding owned by Andrej Babiš – the former prime minister and current leader of ANO, the party currently leading in opinion polls. The group operates clinics in eight countries, from the United Kingdom to Romania, and is one of the fastest-growing parts of Babiš’s business empire.

Between 1994 and 2002, and again in 2013, the Czech Republic experienced a decline in population (see Chart 4). In all of those years, there was a negative natural population change, and in two cases – 2001 and 2013 – it was compounded by negative net migration. Although since the start of the post-communist transition the net migration ratio has generally been positive, it remained modest until 2021, with relatively low levels of both emigration and immigration (see Chart 5). Since joining the EU in 2004, the Czech Republic has stood out in the region for its relatively limited emigration compared with countries such as Poland, Hungary, the Baltic States, or Romania (which joined the EU in 2007). This becomes clearer when comparing the number of emigrants (defined as those leaving for a period of at least 12 months) to the population at the beginning of the year.[23] Between 2013 and 2021, annual emigration from Poland, in proportion to its population, was often around three times higher than from the Czech Republic. Emigration from Romania was generally three to six times higher, from Hungary 1.5 to four times higher, and from Lithuania five to seven times higher by the same measure.[24]

Chart 4. Population of the Czech Republic, 1990–2023

Source: the author’s own estimates based on data from the Czech Statistical Office.

The Czech Republic has historically experienced increased immigration during periods of economic growth, with inflows declining during downturns. This pattern was evident between 2009 and 2013, when immigration declined significantly (see Chart 5). Even after that economic slowdown, until 2015, the number of immigrants arriving in the Czech Republic relative to population remained lower than in Poland or Hungary – in both cases, less than half – and also below levels seen in Romania. This changed as economic conditions improved. By 2016, the Czech Republic had joined the group of EU countries with the lowest unemployment rates, second only to Germany. From 2017 onwards, it has consistently held the top spot in the EU in annual terms.

Despite this, until 2021 immigration remained relatively modest, given the needs of the Czech economy. Employer organisations had long called for greater openness; however, these appeals were met with political resistance rooted in public reluctance to accept more migrants from outside the EU.[25] A major shift occurred in 2022, when the Czech Republic received a large number of Ukrainians following Russia’s full-scale invasion. As of the end of January 2025, the Czech Republic had accepted the highest number of refugees from Ukraine per 1,000 inhabitants in the EU – 36 – ahead of Poland (27) and Estonia (26).[26]

Chart 5. Key migration indicators in the Czech Republic, 1990–2023

Source: the author’s own estimates based on data from the Czech Statistical Office.

Prospects – no way forward without immigration

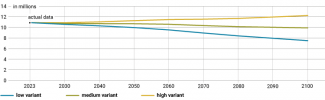

Variant projections prepared by the Czech Statistical Office suggest that the country is very likely to experience a gradual population decline by 2100 (see Chart 6). Two out of the three scenarios presented include this outcome. The media have increasingly reflected these projections in articles written in a notably alarmist tone. One of the starkest examples, published in December last year, warned that ‘if current trends do not change, the Czech population will halve in 200 years, and in 400 years the Czech nation will die out completely’.[27]

Chart 6. Population projections for the Czech Republic to 2100

Source: the author’s own estimates based on data from the Czech Statistical Office.

The medium variant of the population projections prepared by the Czech Statistical Office forecasts a 9% decline in the country’s population between 2023 and 2100 (with a decrease of up to 31% under the low variant). However, this scenario is based on the assumption that the total fertility rate (TFR) will remain constant at 1.5, while it had already fallen below that level in 2023. Given the clear downward trend, it is likely that the rate will drop further in the coming years. A more realistic assumption may therefore be the gradual decline projected in the low variant, with the TFR falling to 1.3 by 2043 and remaining at 1.25 throughout the second half of the century.

In addition to an overall population decline, as expected in the medium scenario, significant changes in the age structure are also projected (see Chart 7). Signs of an ageing society will include an increase in the average age by eight years – nearly one-fifth – between 2023 and 2100, as well as a sharp rise in the proportion of elderly people (up 13.6 percentage points), accompanied by a drop in the share of the working-age population (down 9.2 percentage points). The rapid increase in the economic dependency ratio may necessitate a redefinition of the retirement age unless there is a substantial improvement in economic productivity. A first step in this direction was taken by the centre-right government led by Petr Fiala, which pushed through a pension reform in the final months of 2024.[28] The ageing of Czech society will be driven by two parallel trends: a decline in both the proportion (down 4.7 percentage points) and the absolute number (down 35%) of young people (aged 0–14), and a substantial increase in life expectancy – by 12.5 years for men and nearly 10 years for women (see Chart 7).

Chart 7. Projected change in the population structure of the Czech Republic to 2100 (medium variant)

Source: the author’s own estimates based on data from the Czech Statistical Office.

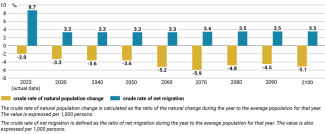

Chart 8. Projected change in selected demographic and migration indicators in the Czech Republic to 2100 (medium variant)

Source: the author’s own estimates based on data from the Czech Statistical Office.

In this context, net migration data will be of key importance – yet in practice, it is extremely difficult to forecast with precision. This is illustrated by the years 2022–2023, which stand out in the long-term trend of this indicator in the Czech Republic. Public solidarity with Ukrainians as victims of Russian aggression resulted in a selective shift in attitudes and – at least temporarily – a socially accepted influx of refugees. However, these sentiments have gradually weakened, and the decline in living standards during 2022–2023 provided far-right politicians an opportunity to connect the two issues in public discourse. While a clear majority of Czechs (73%) still support accepting Ukrainian refugees, the share of those opposing this ‘hospitality’ has risen from 13% in spring 2022 to 23%. At the same time, 40% of the population believes that the integration of Ukrainians has not been successful, and as many as 60% think the country accepted more people than it was able to absorb.[29]

Although the medium variant of Czech projections assumes a gradual increase in the net migration ratio, from 2031 onward this will no longer be sufficient to offset the decline in the crude rate of natural population change (see Chart 8). As a result, the country’s population will begin to shrink. The already acute labour shortage, coupled with the anticipated decline in domestic demand due to a falling population, is likely to increase pressure from Czech businesses to further open the country to immigration from third countries. Without such a shift, there is a risk of social impoverishment and a decline in quality of life, driven by reduced access to public services, particularly at the local level.

[1] See, for example, the report Czeski sukces demograficzny published by the Instytut Pokolenia foundation in October 2022.

[2] For example, in the ‘Health’ category of the Legatum Prosperity Index 2023, which assesses factors such as the quality of healthcare and access to medicines, the Czech Republic ranked 28th out of 167 countries analysed. The remaining V4 countries were placed significantly lower, between 45th and 48th. Similarly, in the most recent edition of the Euro Health Consumer Index (EHCI) published in 2018, which evaluates healthcare quality across Europe, the Czech Republic ranked 14th out of 35 European countries – once again achieving the highest position among the Visegrád Four.

[3] The OECD Better Life Index (latest edition from 2020) assesses quality of life based on 11 parameters. In this ranking, the Czech Republic placed 22nd out of 40 countries, while the other Visegrád Four members ranked between 26th and 31st.

[4] The Human Development Index (latest edition from 2022) reflects the level of socio-economic development. In this ranking, the Czech Republic placed 32nd out of 193 countries, while the other Visegrád Four members ranked between 36th and 47th.

[5] W. Adema, J. Fluchtmann, A. Lloyd, V. Patrini, ‘Paid parental leave: Big differences for mothers and fathers’, OECD, 12 January 2023, oecdstatistics.blog.

[6] The three-year payment period and benefit amount of CZK 350,000 apply to children born on or after 1 January 2024. For those born earlier, a four-year period and a total benefit of CZK 300,000 remain in effect.

[7] OECD data from 2021 (for V4 countries, the figures refer to 2019) cover direct child benefits, family tax credits, support during maternity or parental leave, and assistance for single parents.

[9] ‘Special Eurobarometer no. 545 – Gender Stereotypes’, European Commission, 2024, europa.eu/eurobarometer.

[10] Dane Eurostatu za 2023 r., ec.europa.eu/eurostat.

[11] See ‘Popularita hormonální antikoncepce v Česku klesá. Vědci hledají důvod’, ČT24, 23 August 2021, ct24.ceskatelevize.cz.

[12] D. Krásenská, ‘Dlouholetý hit na ústupu. Antikoncepce českých žen se mění’, Seznam Zprávy, 5 November 2023, seznamspravy.cz.

[13] See K. Dębiec, ‘Fiala's government halfway through its term: security reinforcement overshadowed by economic problems’, OSW Commentary, no. 574, 16 February 2024, osw.waw.pl.

[14] N. Čadová, ‘Public Fears, Feeling of Safety and Satisfaction with the Activities of the Police - Autumn 2023’, Centrum pro výzkum veřejného mínění (CVVM), 16 January 2024, cvvm.soc.cas.cz.

[15] J. Červenka, ‘Citizens on the situation in Ukraine – Autumn 2024’, CVVM, 21 January 2025, cvvm.soc.cas.cz.

[16] ‘Fertility rates by age’, Eurostat, ec.europa.eu. The exceptions were Bulgaria and Cyprus, where fertility rates increased in 2023 following declines in 2022, as well as Portugal, which recorded year-on-year growth in both 2022 and 2023.

[17] From 2001 to 2023, life expectancy in the Czech Republic increased by more than four years – 4.86 years for men and 4.27 years for women.

[18] Poland – 30.8%, Hungary – 31.6%, Slovakia – 27%.

[19] Data sourced from the Czech Statistical Office, vdb.czso.cz.

[20] H. Novotná, ‘Dnes je den neplodnosti. Dětí narozených díky umělému oplodnění přibývá’, Reportáže Radiožurnálu, 6 June 2024, radiozurnal.rozhlas.cz.

[21] The proposed legislation includes provisions such as limiting the number of egg retrieval procedures a woman may undergo to a maximum of six in her lifetime, and setting a cap on the financial compensation that can be offered. Czech media regularly highlight concerns regarding this issue, noting that although assisted reproduction clinics primarily collect eggs from Czech women (97–99% over the past decade), the majority of recipients are foreign women (81–88%). Reports also point to insufficient information provided by clinics – particularly to young patients – regarding potential health risks and complications. See V. Kubant, ‘Žena bude moct darovat vajíčka jen šestkrát v životě. Kompenzace maximálně 28 tisíc, rozhodla vláda’, Czech Radio, 6 November 2024, irozhlas.cz. As of early March, the legislation amendment in question had not yet been passed by parliament.

[22] D. Krásenská, ‘Neplodných párů přibývá. Za děti ze zkumavky platí statisíce’, Seznam Zprávy, 1 June 2024, seznamspravy.cz.

[23] Both figures according to Eurostat.

[24] The author’s own estimates.

[25] See the chapters ‘Aliens are unwelcome in the Czech Republic’ and ‘Labour migration to the Czech Republic from EU member states – the last resort for entrepreneurs’ [in:] K. Dębiec, A country with non-existent unemployment The special characteristics of the Czech labour market, OSW, Warsaw 2019, osw.waw.pl.

[26] Eurostat data, ec.europa.eu.

[27] P. Šafr, ‘10 měsíců do voleb: Češi mají málo dětí a za 400 let vymřou. Sociální dávky to ale nezachrání’, Forum 24, 13 December 2024, forum24.cz.

[28] The reforms were signed into law by President Petr Pavel and have come into effect. Among other measures, they include raising the retirement age from 65 to 67. However, Andrej Babiš, leader of the opposition ANO party and a strong contender to return as prime minister following the autumn 2025 elections, has announced plans to reverse the increase and reinstate the retirement age of 65.

[29] M. Kyselá, ‘Attitude of the Czech public towards accepting refugees from Ukraine – Autumn 2024’, CVVM, 16 January 2025, cvvm.soc.cas.cz.