Central and South-Eastern Europe after the cancellation of South Stream

Russia's withdrawal from the construction of the South Stream gas pipeline has changed the situation on the gas market and has encouraged new dynamics in diversification projects in the countries of Central and South-Eastern Europe. Russia has been attempting to pin the blame for the failure of the project on the European Commission and Bulgaria and hopes to thus mobilise the countries of the region to defend the Russian concept of supplies that bypass Ukraine and provoke a conflict among the countries of the EU; this has not, however, borne fruit. Quite the contrary, after signs of astonishment and indignation, the countries involved in the South Stream project have begun to promote their own infrastructure projects. It is difficult to determine which of the emerging or reactivated projects stand a chance of being implemented and which ones will be the most profitable for the region as a whole. The fact that they are often in competition with one another and that the sources of supplies remain unclear does nothing to decrease this uncertainty. Whatever new projects Russia comes up with, the present situation opens up new opportunities for the countries in the region to look for their own place on the European (the EU and the Energy Community) gas market that is being integrated in a way that is more independent from Russia's political interests. In order to seize this opportunity, important support for the implementation of new infrastructure projects (interconnectors, diversification) from the EU will be required, and this will include financial support. One challenge for the coherence of EU energy policy will be the need to synchronise the interests of the countries from the region and to develop a specific solution to their gas needs, including financial and technical support for the implementation of crucial projects.

Relief in Zagreb and Bratislava

Besides Ukraine, the countries which have the most to gain by Russia's decision to withdraw from the construction of the South Stream pipeline are: Slovakia and Croatia, and also Romania. For Slovakia the implementation of the project would mean losing the status of the key transit country for Russian gas to the EU. Currently, approximately half of Russian gas supplies to the EU transit through Slovakia, which brings financial benefits (in 2013, 257 million euros went to the Slovakian budget in the form of taxes and dividends). Previously the Slovak government had looked for ways to maintain its role in the transit of Russian gas for example by expressing its interest in the project of the Belarus-Poland-Slovakia gas pipeline (peremychka). Several days before the announcement that the South Stream project had run aground, the operator of the transmission system Eustream (co-owned by the Slovak state and the Czech company EPH) put forward an initiative of Eastring. The project is aimed at the construction of an interconnector in Romania, which would connect western gas hubs (including those in Austria) through Slovakia and Ukraine with Romania and Bulgaria. This would probably make it possible to supply gas to Ukraine with the use of Slovakia's main transit route and potentially also to supply gas in the reverse direction – to supply gas extracted in the Romanian gas shelf or sent from Turkey to the West. Eastring would thus be a cheap alternative to South Stream that would integrate the region and enable it to use sources of supplies alternative to those of Russia.

Although Croatia joined the South Stream project and one of the branches of the pipeline was planned to run through its territory, this decision was rather dictated by the fear that Zagreb would be excluded from regional infrastructure connections. However, the implementation of the investment would have shattered Croatia's ambitions to establish a gas hub for the Balkan states and Central Europe. Croatia wishes to take on this role due to the construction of an LNG terminal on the island of Krk and the Ionian-Adriatic gas pipeline (IAP) which would run through Montenegro and Albania and connect the region with the TAP gas pipeline. Croatia is also determined to increase the amounts of gas and oil extracted from the Adriatic shelf. Should the South Stream be constructed, supplies through Croatia would not have been competitive. In the present situation the Croatian government is counting on substantial EU support for its projects. The regional competition with Serbia, which would have benefited from the construction of South Stream and so strengthened its position on the regional gas market, also remains important. If the Russian investment had been implemented, Serbia would have played the main role in gas supplies in the region.

For Romania, as with Croatia, the suspension of the project has provided it with the opportunity to consolidate its position as an important gas producer and transit country. Romania is promoting its own projects – the extraction of gas on the Black Sea shelf, the construction of an LNG terminal and the Vertical Corridor project with a capacity of 3-5 billion m3 which was presented on 9 December and which will link Romania and Bulgaria with the Greek LNG terminal in Revithoussa and the TAP gas pipeline.

In search of the Hungarian contingency plan

Russia's withdrawal from the South Stream project has dealt a blow to the policy pursued by Viktor Orban who until the very last moment opted for the implementation of the project. In November the Hungarian government adopted a law which made it possible to build a pipeline while circumventing EU legislation. On the other hand, South Stream will no longer be a burden in Hungary's relations with its US and EU partners. For Budapest the pipeline had above all a political dimension and was an element of a broader strategy for development of close energy co-operation with Russia; this now looks gloomier due to growing tensions in Russia's relations with the West and the crisis of the Russian economy. For Hungary the key project is the extension of the nuclear power plant in Paks which is to be conducted by Rosatom. Although on 9 December three contracts were signed: for the construction of reactors, to operation of power plant and for fuel supplies . However, there are growing concerns in Hungary about the future of the project since 80% of its financing is meant to be provided by a Russian loan.

The Hungarian government continues to emphasise the need to bypass Ukraine and is against the halting of work to make it possible to supply Russian fuel from the south, for example by the construction of a Russian gas pipeline with the participation of Turkey. However, the failure of the South Stream project will not lead to serious losses for Hungary. Although Hungary would benefit from the role of a transit country in supplies of Russian fuel through South Stream (en route to the gas hub in Austria), this would not substantially strengthen energy security as the gas pipeline would not lead to a diversification of supply sources. It is no accident that interest in other concepts of diversification has been revived in Hungary; the concepts are as follows: access to gas from Azerbaijan (for example AGRI, TAP-IAP); the Romania-Hungary-Austria gas pipeline which would transport gas from recently discovered sources in Romania; the construction of connectors between Greece, Bulgaria, Romania and Hungary; and the North-South gas corridor that would also include the possibility of supplies from LNG terminals.

Bulgaria and Serbia

It was for Bulgaria and Serbia that the construction of South Stream had most importance as they are totally dependent on Russian gas supplies through Ukraine. The Russian pipeline for them would have been something more than merely an alternative route of supplies—it was planned to ensure considerable revenues from gas transit with the minimum of their own funding being used and it would have enhanced the strategic role of both countries.

The previous Bulgarian government of Plamen Oresharski provided the project with great support, occasionally taking measures which were not consistent with EU legislation. However following a fierce dispute with the European Commission, it decided to suspend implementation of the project until it became adjusted to EU requirements. As a consequence, Moscow came to consider Bulgaria, alongside the European Commission, as the main culprit responsible for the failure of the project. Russia's fierce attacks against Bulgaria make it even easier for the present Bulgarian government of Boyko Borisov to distance himself from the project and they have contributed to weakening what had until then been quite wide support in Bulgaria for the implementation of the project. The questions concerning its profitability and the benefits it was supposed to bring to the Bulgarian economy and their political price returned. At the same time Russia's attacks against Bulgaria lend credibility to the Bulgarian government within the EU and may increase the effectiveness of its efforts to secure larger EU support for alternative projects. The Bulgarian government has started laying out the construction plan for the Vertical Corridor with Romania and Greece and has presented the European Commission with the construction plan for a large gas storage facility.

Serbia, seeking to obtain EU membership, has ceded the negotiation of the agreement concerning the construction of a gas pipeline with Russia to the European Commission. As Serbia assumed that the implementation of the investment depends on the EU and Russia, it avoided taking measures which could lead it into dispute with either of the parties. The abandonment of the project has astonished the Serbian government and challenged the strategy for the development of the energy industry in co-operation with Russia, which has been championed by the pro-Russian gas lobby and a section of the political elites, and has weakened Moscow's credibility as a partner. The disappointment in Belgrade is even larger because it is commonly believed that Serbia sold the main refinery company (NIS) to Russia below market price in exchange for the construction of South Stream, since its construction would have secured Serbia a strategic role in the region. However, at the same time the implementation of the investment would mean Russia taking over total control of the Serbian energy industry. Russia's decision may even make it easier to reform the Serbian gas industry; furthermore, Belgrade is hoping that the construction of infrastructure connections, for example support for the Niš-Dimitrovgrad connector with Bulgaria, will be included in EU construction plans.

The outlook

Russia had been expecting a resounding defence of the South Stream project and tensions within the EU. However, the countries of the region responded to the decision to abandon the investment by presenting alternative projects aimed at ensuring the security of gas supplies. Furthermore, they have begun to challenge the benefits of the Russian project which has recently dominated the discussion on energy security in this part of Europe. There has also been an additional economic impulse to consider alternative projects for Ukraine demand for gas supplies from the western direction. Withdrawing from the South Stream project provides an opportunity to develop a new strategy to build the infrastructure which will take into account the EU’s priorities to integrate gas markets and diversify sources of supplies. Nevertheless, the countries from the region are above all counting on larger (in both financial and technical terms) EU involvement in ensuring the security of gas supplies and they have high hopes for the proposal submitted by the President of the European Commission Jean-Claude Juncker regarding the establishment of the European Fund for Strategic Investments.

The European Commission has already taken its first steps towards this. On 9 December regional infrastructure priorities were discussed with representatives of the EU countries involved in the South Stream project and a high-level working group has been set up in order to facilitate putting these priorities into practice. On the other hand, the European Commission is not ruling out the implementation of the project as long as it is implemented in line with the EU acquis. Germany holds a similar position on this, which could be seen in the speech made by the German Chancellor during her visit to Bulgaria on 15 December. In the present situation it should be expected that if Russia presents new gas co-operation projects, it will be indisputably required to adjust them to EU legislation and the proposal put forward by the European Commission will be stronger.

Support for the implementation of infrastructure projects could become the foundation for a more durable involvement of the countries in South-Eastern Europe in EU energy policy and could thus facilitate the establishment of an Energy Union. However, urgent measures are needed, including the implementation of selected interconnectors, LNG terminals, the North-South Corridor and the use of west Ukraine’s infrastructure (gas pipelines and gas storage facilities).

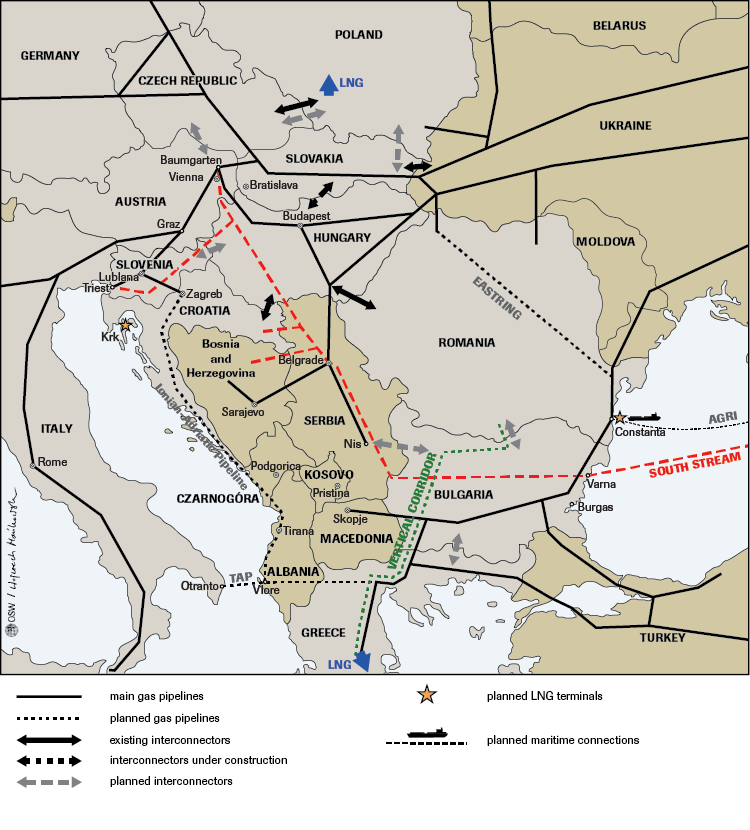

Map

Selected gas infrastructure projects in the region

Co-operation: Mateusz Gniazdowski, Jakub Groszkowski, Agata Łoskot-Strachota, Andrzej Sadecki