A dwindling nation. Bulgaria is on the brink of a demographic collapse

The greatest challenge Bulgaria will face in the coming decades is addressing the persistent negative trends associated with depopulation. The country’s demographic crisis has been worsening for years, with the population steadily declining over the past three decades. Bulgarian society, which continues to have one of the lowest average life expectancies in the EU, suffers from a significant imbalance between younger and older age groups. These challenges are further exacerbated by the ongoing and increasing emigration of economically active Bulgarians.

Bulgaria has been struggling with serious demographic issues for a long time, but it is only in recent years that these issues have entered public discourse. This discussion not only diagnoses the issue but also suggests measures to address it. However, the ongoing political crisis of recent years, characterised by frequent parliamentary elections occurring every few months, has hindered the development of an ambitious strategy to address the demographic decline through public policy.

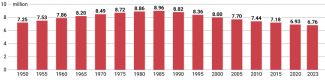

Key demographic indicators and projections reveal a severe generational replacement crisis in Bulgaria. At its peak in 1987, the country’s population stood at 8.976 million. By 2024, this had declined by over 2.2 million, representing a 27.5% reduction. Following World War II, the population grew steadily from the mid-1950s, with minor declines in the late 1970s and 1980s, until the collapse of the communist system.

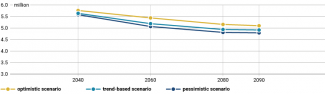

Since 1990, Bulgaria has recorded negative natural population growth, estimated at -0.6% in 2024. In 2023, 62,000 Bulgarians were born, compared to 155,000 in 1950. The most pessimistic long-term projections indicate that, if the negative growth rate – expected to reach -0.73%,[1] by the early 22nd century – persists, Bulgaria’s population could diminish to just 3.5 million by 2100.

A confluence of negative factors

Bulgaria’s low birth rate does not differ significantly from those in most European countries. Regarding the fertility rate (the average number of children born to a woman of reproductive age), Bulgaria’s figures, ranging between 1.1 and 2.0 since 1990, are consistent with the EU average of 1.46. Likewise, the average age of Bulgarians, at 44.5 years, is similar to that of Poland and Germany.

The consequences of low fertility are particularly evident in the correlation between an ageing society and a steadily declining working-age population. According to the most recent census conducted in 2021, the number of economically active Bulgarians exceeded 4 million, accounting for 62% of the country’s population. This figure marks a decline of more than 900,000 (approximately 19%),[2] compared to the previous census in 2011.

Chart 1. Bulgaria’s population from 1950 to 2023

Source: National Statistical Institute of the Republic of Bulgaria, nsi.bg.

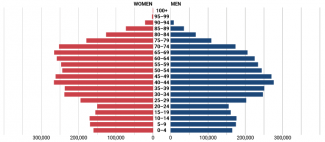

The age imbalance within Bulgarian society is evident in the increasing numerical disparity between two groups: young people (under 30) and those of retirement age (over 60). In 2022, individuals aged over 60 accounted for 23% of the population. A second negative trend is the emigration of working-age Bulgarians (18–50 years), particularly among the educated and skilled workforce.

Improvements in the macroeconomic situation, economic growth, and reduced unemployment following Bulgaria’s EU accession in 2007 resulted in a temporary increase in the birth rate, from 9.1 in 2000 to 10 between 2008 and 2010. This period also marked the peak fertility rates of individuals born in the mid-1970s and early 1980s. However, by 2016, the birth rate had already declined to 9.4.

The coming-of-age of the millennial generation provides little prospect of reversing these trends in the short term. A 2023 survey revealed that nearly half of Bulgarians aged 18–35 expressed a desire to delay having children indefinitely.[3] Since 2020, annual births have fluctuated between 59,000 (in 2020) and 62,000 (in 2023). Furthermore, between 2010 and 2020, the number of women of reproductive age decreased by nearly 200,000, a trend that has continued despite a rise in births to mothers aged 40 and above (2,140 in 2022, increasing to 2,654 in 2023). Projections for 2030 forecast a further decline in the population of women of reproductive age,[4] by nearly 500,000.[5]

Like most European countries, Bulgaria is undergoing social transformations marked by the increasing fragility of marital relationships, a significant proportion of non-marital births, and high abortion rates. Since 1991, the country has witnessed a steady rise in divorces and a decline in the number of new marriages.[6] Over the past decade, 59% of children were born outside marriage, with higher rates in rural areas (65%) compared to urban areas (57%). Notably, more than 30% of children born during this period were registered in civil records without a named father. Bulgaria also ranks among the top European countries in terms of the ratio of abortions to births. According to data from the National Centre of Public Health and Analyses (NCPHA), the annual number of officially recorded abortions ranged from 31,000 in 2010 to 17,000 in 2023. The NCPHA further estimates that nearly 150,000 married couples of reproductive age may experience temporary infertility or permanent sterility.[7]

The decline in Bulgaria’s population is further exacerbated by high mortality rates. This trend worsened during the COVID-19 pandemic, which resulted in the highest death toll since World War I. In 2020, over 150,000 deaths were recorded – a figure nearly 37% higher than in 2019. In the early 1990s, the mortality rate was aproximtaely 14.1–14.7, rising to 15.1 by 2016. Between 2011 and 2019, the country’s population decreased by an average of 50,000 people annually. Following the pandemic, mortality levels have remained high, with 41,000 deaths recorded in the first half of 2023 alone.[8]

The scale of Bulgaria’s demographic crisis is a result of a confluence of two factors: the country has one of the lowest life expectancies in the EU (74.7 years) and one of the oldest populations in Europe. This dynamic creates significant demographic imbalances between younger and older generations, as evidenced by the stark disparity between the number of individuals entering the workforce each year and those retiring.

During the first decade of the 21st century, Bulgaria’s demographic replacement ratio was progressive, standing at 100 to 124, meaning 124 individuals entered the workforce for every 100 reaching retirement age. However, since the beginning of the current decade, it has become permanently regressive, with a ratio of 100 to 62, meaning only 62 new workers replace every 100 retirees. This trend now affects all 28 provinces of Bulgaria.[9]

Chart 2. The imbalance between Bulgaria’s younger and older generations

Source: National Statistical Institute of the Republic of Bulgaria, nsi.bg.

The two axes of development and stagnation

Alongside demographic imbalances, Bulgaria’s demographic crisis is influenced by horizontal (geographical) developmental disparities. Areas with a young, economically active population are concentrated along two main axes: the north-south Sofia–Kulata axis and the east-west Sofia–Burgas axis, with a deviation towards Varna. Depopulating regions include the northern and central provinces, as well as mountainous areas such as parts of the Rhodopes and the Strandzha–Sakar ranges.

In some municipalities (Bulgarian: община), particularly in the north-western region, the mortality rate reaches 30, a level comparable to underdeveloped Global South countries afflicted by chronic armed conflicts. A significant urban-rural disparity also exists. By the end of the previous decade, the mortality rate in Sofia and six other cities with populations exceeding 100,000 (Plovdiv, Varna, Burgas, Ruse, Stara Zagora, and Pleven) was 12.9, compared to 21.1 in rural areas. The provinces of Montana, Kyustendil, Vidin, and Gabrovo (in north-western Bulgaria) report the lowest ratio of retirees to new workforce entrants – on average, only 50 individuals join the workforce for every 100 retirees.[10]

The demographic imbalance between urban and rural areas is further highlighted by higher birth rates in Sofia (9 per 1,000 residents in 2020) compared to the depopulating and less developed northern and western regions, such as Vidin and Gabrovo, where the rate was only 5 during the same period.

The pace of rural depopulation is illustrated by a decline of over 33% in the rural population between 1992 and 2016. During the same period, the population in Sofia and other cities with over 100,000 residents declined by only 8.6%. By the end of the last decade, 73% of Bulgarians lived in seven cities – Sofia, Plovdiv, Varna, Burgas, Ruse, Stara Zagora, and Pleven – and this figure is projected to rise to 76% by 2030.

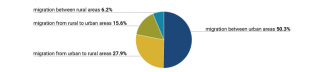

These trends are exacerbated by disparities in internal migration. Since 2020, approximately 190,000 Bulgarians have relocated within the country each year. Around 77% of these moves involved migration from rural to urban areas or between cities. Men and women migrated in nearly equal proportions (49% and 51%, respectively), as did individuals aged 20–39 (28%) and 40–59 (29%). By contrast, migration from cities to villages accounted for only 15% of total migration over the past five years, while movements between rural areas represented merely 6%.[11]

The depopulation of rural Bulgaria also carries practical implications for internal security. Abandoned and derelict farms and homes – particularly in the northern and central parts of the country – have increasingly become sources of wildfires, especially during the prolonged droughts that have afflicted these regions in recent years. The Ministry of Interior estimates that these fires result in material losses amounting to nearly €1.9 billion annually.[12]

Chart 3. Internal migration within Bulgaria

Source: National Statistical Institute of the Republic of Bulgaria, nsi.bg.

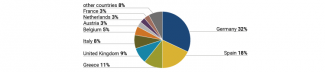

Chart 4. Major destinations for Bulgarian emigrants

Source: National Statistical Institute of the Republic of Bulgaria, nsi.bg.

Negative migration balance

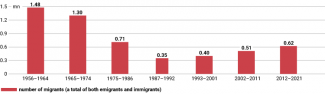

Migration imbalances in Bulgaria are also evident in external migration patterns. According to estimates from the Executive Agency for Bulgarians Abroad (IABCh), between 2.8 and 3.5 million citizens have emigrated without returning since the start of the political transition. During the first two decades of this transition – up to 2011 – external migration accounted for 32% of the total population decline. Throughout much of Bulgaria’s democratic era, the number of emigrants has significantly exceeded the number of immigrants.

This trend was first disrupted by the pandemic and then was expected to change, given the arrival of nearly 140,000 war refugees from Ukraine in the first half of 2022. In 2020, the year of the pandemic, the number of emigrants dropped sharply from 39,000 in 2019 to 6,500. In 2021, migration balance remained positive, with 39,000 people settling in Bulgaria and 26,000 leaving. According to other estimates by the IABCh, there may now be 8–9 million people living abroad who have at least one parent born as a Bulgarian citizen.[13]

Between 2010 and 2020, Bulgaria’s population declined by over 175,000 due to emigration. The main destinations were Germany (22%), Russia (14%), and Turkey (13%). A regional phenomenon, also observed in neighbouring Serbia, has been the economic migration of Bulgarians to Russia. This primarily involved working-age men employed in Russia’s mining and fuel-energy sectors. According to the most recent data from 2019, approximately 15,000 Bulgarians aged 19–29 were enrolled in higher education or post-secondary programmes in Russia.[14]

Since the Arab Spring and the European migration crisis, Bulgaria has also emerged as a destination for migrants. Between 2010 and 2020, an average of 1,500 to 3,500 individuals applied annually for permanent residence, with men accounting for the majority (54%). The most common reasons for settling in Bulgaria were marriage to a Bulgarian citizen (67%), permanent employment (16%), and education (12%). As many as 91% of migrants came from outside the EU, predominantly from the Global South (57%), Turkey (24%), and Russia (10%). Only 9% of migrants originated from EU countries, primarily Germany, the Benelux states, and the United Kingdom. Among this group, returning emigrants or individuals of Bulgarian descent constituted the majority. People aged 20–59 made up 60% of non-Bulgarian citizens migrating to Bulgaria.[15]

Migration triggered by the Russian invasion of Ukraine has thus far had minimal impact on Bulgaria’s demographic situation. Data from 2023 showed that only 12,000 Ukrainians expressed a desire to settle permanently in the country, while their total number in Bulgaria at the end of 2023 was estimated at approximately 52,000. Following the pandemic-related anomaly and the temporary influx of refugees in 2022, the migration balance remains negative, with emigration continuing to significantly outpace immigration.

Chart 5. Migration in Bulgaria from 1956 to 2021

Source: National Statistical Institute of the Republic of Bulgaria, nsi.bg.

Crisis vs. ethnic diversity

The demographic crisis affects both ethnic Bulgarians, who constitute 84.5% of the population (over 5.1 million) according to the most recent census, and the largest minority groups: Turks, representing 8.4% of the population (over 508,000), and Roma, accounting for 4.4% (266,000). Compared to the 2011 census, both minority groups experienced similar population declines of 0.4% and 0.5%, respectively. This decline is likely linked to emigration, particularly among the Roma community. Furthermore, the census figures for the Turkish and Roma minorities may be understated due to a reluctance to self-identify as non-Bulgarian. In the latest census, over 64,000 individuals refused to answer the question about ethnic background, while 16,000 reported being unable to define their ethnic identity precisely.

Differences in age profiles further highlight the ageing of the ethnic Bulgarian majority and the relative vitality of the Roma minority. Children under the age of 14 comprise 26% of the Roma population, compared to 14% of Bulgarian Turks and only 12% of ethnic Bulgarians in the same age group.

Chart 6. Demographic development projections for Bulgaria: trend-based, optimistic, and pessimistic scenarios

Source: National Statistical Institute of the Republic of Bulgaria, nsi.bg.

Government strategies to address the crisis

The government introduced its first strategies to address the issues of Bulgaria’s demographic development and crisis only in 2006. These strategies generally adopt a medium-term outlook, extending to approximately 2030. The primary body responsible for preparing, coordinating, implementing, and evaluating these strategies within the state governance structure is the Ministry of Labour and Social Policy.[16] Over the past five years, mechanisms for coordinating public administration efforts with academic circles have been enhanced, and, on the initiative of President Rumen Radev, the National Council for Demographic Policy (NSDP) was established within the government.

The core demographic development strategy is the National Strategy for Demographic Development and Population of the Republic of Bulgaria for 2012–2030,[17] adopted during the first cabinet of Boyko Borissov in 2012 and updated biennially. Its objectives are to slow the population decline and stabilise the demographic outlook by 2030. This is to be accomplished through investments in human capital development, healthcare, education, and vocational training. The strategy seeks to mitigate the negative effects of demographic inequalities – particularly between rural and urban areas – on public finances and the social security system.

In 2019, under the third government of Boyko Borissov, a separate strategy was adopted to address the challenges posed by an ageing population. The National Strategy for Active Ageing in Bulgaria (2019–2030)[18] advocates for greater inclusion of individuals over the age of 55 in active social life and local community engagement. Key components of government strategies introduced in recent years include increased budget transfers to depopulating rural areas, investments in the education system aligned with plans for reindustrialisation and labour market renewal in these regions, housing policy development, and incentive programmes for highly skilled Bulgarian labour emigrants. These incentives are designed to encourage their return by facilitating the establishment of businesses, particularly start-ups.

However, the implementation of these strategies and proposals remains problematic, with many confined to a declarative stage. During the initial two decades of the transition period, this was attributable to the political class underestimating the importance of demographic issues. Today, it results from a chronic lack of stable executive power, which significantly hinders the implementation of comprehensive pro-natalist, housing, and migration policies.

State support system to boost the birth rate

Since the 1960s, Bulgaria has maintained a state support system for families and children aimed at promoting higher birth rates. However, compared to other EU countries, particularly the Visegrád Group, funding allocated to this programme remains relatively modest. As in other European nations, experts contend that direct subsidy programmes, while undeniably necessary, cannot sustainably stimulate demographic growth unless they are combined with housing policies and broader development strategies. These strategies should focus on encouraging individuals of reproductive age to remain in the country and establish their families and careers there.[19]

The family allowance system primarily supports the poorest families, defined as those earning less than the statutory minimum wage, which in 2024 was approximately €400. In that year, monthly benefits were set at around €25 for one child, €56 for two children, €84 for three or four children, and increased proportionally by approximately €10 per child for larger families. Monthly allowances for twins were approximately €35. Income thresholds are enforced – families or parents earning slightly above the minimum wage receive only 80% of the corresponding benefit amount.

Child disability benefits in Bulgaria have not been adjusted since 2015. These benefits range from approximately €603 per month for the highest degree of disability to around €230 for mild disability.

For the first two years following the birth or adoption of a child, families receive an annual assistance payment of approximately €398. If additional paid parental leave for raising a child under the age of two is not utilised, families receive a reduced payment of around €199, roughly half the standard amount. Single parents are eligible for a monthly allowance of approximately €92 until the child reaches the age of three. A one-time maternity benefit upon the birth of a child currently amounts to approximately €191. Mothers are permitted to transfer their maternity leave to the father or even to grandparents after six months from the child’s birth, provided the recipient is employed or in public service.

The final element of the system designed to increase birth rates consists of child tax relief. The amount varies depending on the number of children and the taxpayer’s income bracket. For one child, under the lowest tax bracket (10%), the annual tax-free allowance is approximately €3,000.

Prospects

The ongoing crisis in Bulgaria’s executive branch, marked by an inability to form a stable majority government, hinders the consistent implementation of demographic policies. Interim governments tend to prioritise ad hoc administration and preparations for upcoming parliamentary elections rather than pursuing comprehensive social programmes. President Rumen Radev has sought to leverage these challenges, criticising successive governments for their failure to maintain a consistent demographic policy.

Simultaneously, a consensus is beginning to emerge among Bulgaria’s main political forces concerning the fundamental strategies for addressing the demographic crisis. Between 1990 and 2006, this issue was largely neglected and marginalised in political debates. However, over the past decade, it has risen to the forefront of public and governmental concerns. There are even proposals to subject every new parliamentary law relating to economic development to ongoing evaluation from a demographic perspective.

All demographic projections for Bulgaria in the coming decades remain bleak, with none anticipating a resolution to the crisis. In the face of a politically and socially challenging domestic situation, as well as broader European trends of population decline, rooted in civilisational and cultural factors, identifying an effective solution is far from straightforward. This situation is further compounded by widespread passivity and resignation – Bulgarians rank as the most pessimistic nation in the EU and among the most pessimistic globally.[20] A fatalistic belief that the nation is diminishing and losing influence on international processes exacerbates this sentiment.

An increase in societal wealth and well-being in Bulgaria will not automatically improve its dire demographic situation, but it could serve as a foundation for mitigating the most negative forecasts, which predict that the country’s population could shrink by nearly half over the next century. The ongoing population decline, combined with an ageing society, will lead to a contraction of Bulgaria’s economy, which already holds a peripheral position, thereby further weakening the state.

In Bulgaria, there is a widespread belief that migration from non-European countries is not a solution to the demographic decline and the associated future labour shortages. The media often portray migrants negatively, as culturally foreign and a threat to internal security.[21] This narrative makes it challenging for successive interim governments to develop a comprehensive immigration policy.

Against this backdrop, the Bulgarian public tend to pin their hopes for demographic improvement more on the potential return of Bulgarians from abroad. Between 2012 and 2023, annual returns ranged from 5,000 to 24,000, peaking during the pandemic. The countries most frequently associated with returnees after years of economic or educational emigration are Turkey and Russia, suggesting that these returns may be driven by non-economic factors, such as global and regional security concerns. Consequently, it is likely the number of returns will stabilise or decline to just a few thousand annually in the coming years. Government support is expected to focus on this group, offering incentives for permanent resettlement, entrepreneurship, and professional engagement in Bulgaria. Assuming the continued instability of the executive branch, such targeted measures may effectively be the only short-term measure capable of mitigating the demographic crisis.

[1] Г. Бърдаров, Н. Илиева, Хоризонт 2030. Демографски тенденции в България, Фондация Фридрих Еберт, Sofia 2018, p. 4.

[2] Population projections by sex and age, National Statistical Institute of the Republic of Bulgaria, 14 November 2023, nsi.bg.

[3] A. Маркарян, Все повече българи искат 3 деца, но много остават бездетни, 23 November 2023, offnews.bg.

[4] С.С. Георгиев, България 2019 – Нови хоризонти Съмнения, надежди, перспективи, Институт за Социална Интеграция, Фондация Фридрих Еберт, Институт за Социална Интеграция Фондация Фридрих Еберт, София 2019, p. 108.

[5] Г. Бърдаров, Н. Илиева, Хоризонт 2030…, op. cit., p. 16.

[6] Zob. Бракове, бракоразводи и раждания в България в началото на 21 век, Eurostat, ec.europa.eu.

[7] ‘Извършени аборти през 2023 r.’, National Centre of Public Health and Analyses, 3 October 2024, ncpha.government.bg.

[8] ‘Deaths in Bulgaria by weeks’, National Statistical Institute of the Republic of Bulgaria, 12 February 2024, nsi.bg.

[9] Г. Бърдаров, Н. Илиева, Хоризонт 2030…, op. cit., p. 7.

[10] ‘Все повече хора в трудоспособна възраст умират преди пенсия’, 25 October 2024, faktor.bg.

[11] Internal migration of the population between towns and villages by sex, National Statistical Institute of the Republic of Bulgaria, 29 April 2024, nsi.bg.

[12] Е. Танева, ‘Отпускат 1,9 млн. лв. по de minimis за щети на земеделци и фермери от пожарите’, On Air Bulgaria, 22 October 2024, bgonair.bg.

[13] ‘Извън пределите на България живеят между 8 и 9 млн. българи’, 7 July 2017, btvnovinite.bg.

[14] ‘Роберт Шестаков: 15 хиляди българи учат в университети в Русия’, 22 February 2019, trud.bg.

[15] З. Вълчанова, ‘Демографската криза е проблем за българската икономика. Как може да се разреши?’, 25 October 2024, ivestor.bg.

[16] Демографска политика, Ministry of Labour and Social Policy of the Republic of Bulgaria, 15 September 2024, mlsp.government.bg.

[17] Актуализирана Национална стратегия за демографско развитие на населението на Република България 2012 – 2030 г., Национални стратегически документи, Ministry of Labour and Social Policy of the Republic of Bulgaria, 12 July 2024, mlsp.government.bg.

[18] Национална концепция за насърчаване на активния живот на възрастните хора 2012 – 2030 г., Национални стратегически документи, Ministry of Labour and Social Policy of the Republic of Bulgaria, 15 October 2024, mlsp.government.bg.

[19] З. Славова, ‘Детски надбавки за всички – справедливост или популизъм’, 10 October 2020, mediapool.bg.

[20] See Gallup International survey results, 1 December 2020, gallup-international.bg.

[21] See ‘Gallup international comments refugee issue in Bulgaria’, Bulgarian National Radio, 19 November 2019, bnr.bg.