The Russian operation in Syria: the consequences for the region

The Russian operation in Syria has marked Russia’s spectacular return to the play for the Middle Eastern as a major military and political player able to change the dynamics of the game in both Syria and the region as a whole.

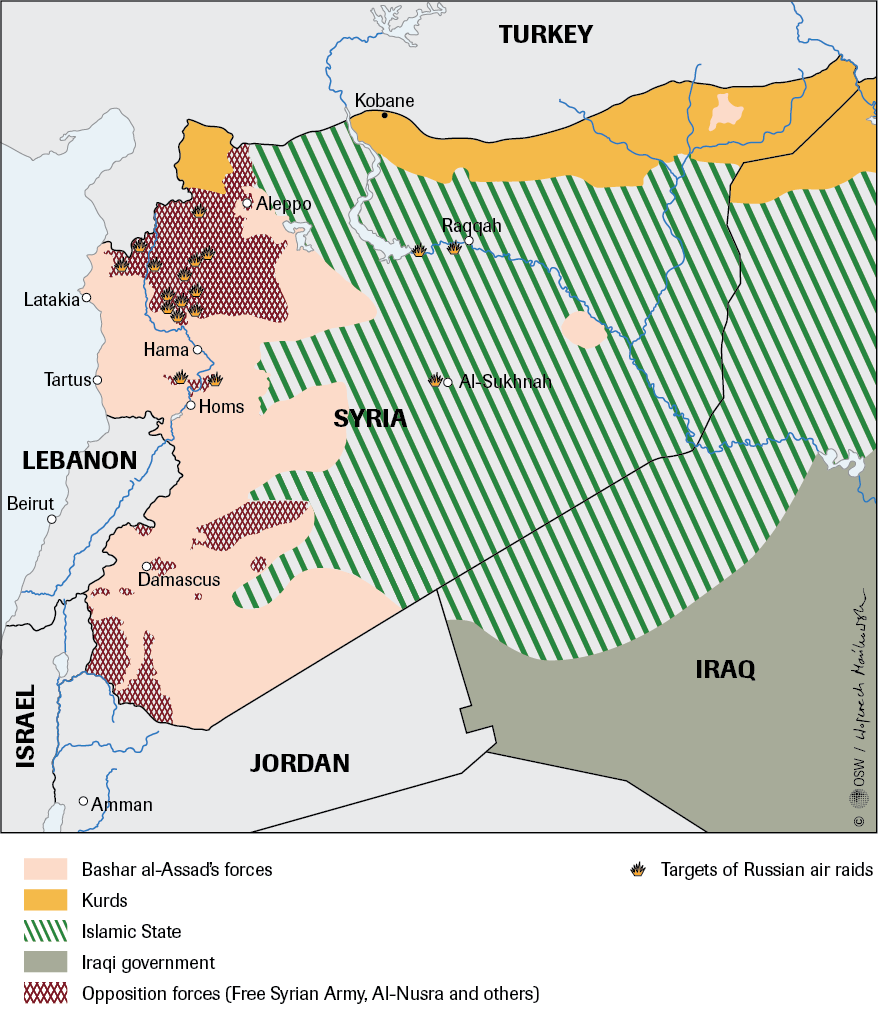

The strength of the Russian strikes has upset the existing balance of powers in the Syrian conflict, directly reinforcing the Assad regime. The Russian moves have laid a solid foundation for the expected ground offensive of government troops and allied Iranian and Hezbollah forces, which would make it possible to regain control over what the regime views as strategic points. The main target of the present and future attacks are the troops of Jabhat al-Nusra and the Free Syrian Army, which are viewed as direct threats by al-Assad. Islamic State and the Kurds are not considered dangerous, and therefore they are not under attack at present and their position in Syria has been strengthening.

Russia’s moves so far in Syria have had serious consequences for the region. The relative balance has been tipped to the disadvantage of states hostile to al-Assad and Iran (Saudi Arabia, Israel and Turkey), while Iran’s position and room for manoeuvre have been enhanced significantly. This is likely to stimulate regional tension and escalate a proxy war in the region, with all the negative consequences that it entails (including another wave of refugees).

Russia’s recent moves in Syria prove that it still has a strong influence in this region – but this is above all the potential for destabilisation and the limited channelling of tension. It seems quite unlikely that Russia will or could become an equal and positive player in the region; its assets are limited to its military contingent and co-operation with either very weak (al-Assad) or strong and ambitious players (Iran). Furthermore, it has limited means at its disposal, and the region needs its serious presence only to minimal extent.

OSW analysis about the details of the Russian operation in Syria

A new beginning in Syria?

Given the long duration of the conflict, the fatigue of the parties to it, the wear and tear of the equipment used by all its participants, etc., the recent Russian moves have had a very strong impact on the conflict. The previous Russian air raids were targeted at the groupings which posed a direct threat to al-Assad and at the areas of greatest military significance for the regime. Thus the relative balance on the frontline between the government forces and the fragmented and internally conflicted opposition camp has been upset (the regime has controlled more or less the same area over the past 2-3 years), and the vision of al-Assad’s defeat has definitely become less realistic (local defeats in 2015 suggested that he was weakening). Given this context, even the small number of the attacks concentrated this time on the Free Syrian Army and Jabhat al-Nusra have significantly strengthened their competitors and opponents (the regime, the Kurds and Islamic State).

Russia’s engagement in the conflict in Syria also suggests that some strategic redefinitions might be made: Russia is becoming the face of the informal pro-Assad coalition (Russia, Syria and Iran), contributing a serious military component (air forces which were in practice absent in Syria). In effect Iranian troops can become – in Russia’s shadow – engaged to a greater extent in the conflict. Their presence has been essential for the regime’s survival so far, but it has been discreet and has taken the form of sending instructors, equipment, limited numbers of its own troops and troops of Hezbollah and Iraqi Shia militias. An additional corps of the Army of the Guardians of the Islamic Revolution (elite al-Quds troops) consisting of around one thousand soldiers have reportedly arrived in Syria in the past few weeks. Given the Russian dominance in the air, Iranian support and the possibility to use regular Syrian troops, the scenario in which the regime would launch an offensive, destroy and take control of key points on Syria’s map is becoming increasingly realistic. Considering the brutality of the conflict seen so far, a massive exodus of the civilian population (Arab Sunnis fleeing from Assad’s forces and Iranians) from the territories occupied by the regime may be expected. One effect of this would be to facilitate the pacification and subsequent control of the conquered areas. Given the Russian moves, the likely offensive will be targeted at securing and consolidating the strip of land connecting Damascus with the coastline, i.e. against the opposition troops located between Hama and Homs. It cannot be ruled out that further attempts will be made to recapture the part of Latakia province occupied by rebel forces or Idlib province.

…and in the region

The conflict in Syria is nothing more than the most severe form of the broader crisis in the Middle East. All countries in this region (especially those neighbouring on Syria) have been engaged in it for years, supporting and using individual actors in this conflict for their own purposes, incurring its costs and making efforts to ensure that their own strategic goals are implemented. Given this situation, even the limited Russian activity underway for less than a week has called the system of calculations, mechanisms and co-dependencies existing between them so far into question. This above all concerns the players engaged in combating al-Assad (see below) who are Iran’s rivals (who view its increasing influence as a threat) and who fear Islamic State’s expansion. The Russian policy has already reduced the likelihood that they will achieve their goals, since they would then have to face direct military confrontation with Russia.

In this context, the most important consequences are for:

- Saudi Arabia, which has been in a strategic conflict with Iran. Russian support to al-Assad will thus mean that Iranian influence, which is already predominant in Iraq (real control of the Iraqi state structures) and successful in Yemen (support for anti-governmental Houthi Shia groupings), will become even stronger. The weakening of the Free Syrian Army and of the Sunni Islamic radicals (who are informally supported by the Sauds) also creates more room for Islamic State. If actions against IS were to be intensified, this organisation could be pushed further south (i.e. to the areas inhabited by Sunni Arabs) and pose a threat to the Sauds. Riyadh has officially criticised the Russian operation, non-governmental circles have appealed for action to be taken against Russia (including jihad), and the decision to reduce crude oil prices (which runs counter to Russian interests) has been made (prices were reduced by US$1.7 per barrel on 4 October).

- Israel, which views a possible strengthening of Iran’s position in Syria and Lebanon as a strategic threat. Taking into account the Israeli government’s concerns, Russia has refrained from attacking targets within its immediate neighbourhood (i.e. it has not upset the local balance) and has been engaged in intense high-level military consultations. It is becoming more likely that Israel will make unilateral moves – as it did on many occasions in the past – against targets in Syria and Lebanon (above all against Hezbollah), while avoiding direct confrontation with Russia.

- Turkey, from whose point of view the recent Russian moves have in fact scuppered the Turkish policy aimed at removing al-Assad (and more broadly, at ensuring dominance in Syria and leadership in the Middle East), and has thus seriously undermined its international standing. Russia’s support for al-Assad will also seriously increase the costs of creating a security zone in northern Syria, which Turkey has consistently mentioned since almost the beginning of the war. Over the past few days, Turkey has unambiguously criticised the Russian moves, intensified its diplomatic efforts to create a security zone, increased support for Syrian groupings (bombarded by Russians) and continued attacks on Kurdish targets in Iraq (the main stronghold of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party). Symptomatically, Turkish airspace has been violated twice during the Russian operations; this needs to be treated as Russia checking how Turkey (and also NATO) will respond and also as a warning. However, given the scale of the challenges (both internal and external), it cannot be ruled out that Turkey may decide to take more active and aggressive measures in Syria but only if its actions are supported and coordinated with the West, especially the USA, and even then with great reluctance.

The recent Russian moves pose a threat to the interests of some countries, and at the same time bring a positive stimulus to the remaining players. This concerns both Iran and Syrian Kurds who Ankara treats as a threat to Turkey’s territorial integrity and as a direct support base for PKK’s military operations in Turkey (which were resumed with new strength in July this year). This change took place just weeks ahead of the snap parliamentary election (scheduled for 1 November), which is extremely important for the Turkish government. Kurds have taken a neutral stance on al-Assad—their main enemy is Islamic State (in this context they are the main ally of the USA and receive US support). They remain, however, in strategic confrontation with Turkey (whose interests Washington must respect) and are in rivalry with Iraqi Kurds who have links with Turkey (the Kurdistan Democratic Party led by Masoud Barzani). In this situation, they greet Russia joining the game with great hope: the leader of the Syrian Kurds, Salih Muslim, has expressed his will to co-operate with Russia, thus revealing his hidden hope for a protectorate over what is really a Kurdish autonomy in Syria.

Conclusions

Regardless of the spectacular success (above all in the media) of the Russian intervention in Syria, a coordinated operation of ground troops of Syria, Iran and Hezbollah supported by Russian air forces would be the real test of success. A successful offensive might cause a deep marginalisation of some of the opposition forces and a relative strengthening of others (Islamic State and Kurds), and hand the initiative back to the regime in Damascus.

The Russian operation in Syria, both at present and possibly in the future, has a vast destabilising potential for the entire region: it adversely affects the strategic interests of many countries, intensifies rivalry in the region, poses the threat of the escalation and expansion of conflicts, for example, the Kurdish issue in Turkey and Iraq, radicalisation in Arab countries, and a further escalation of the Sunni-Shia conflict. Each variant offers significantly increasing room for manoeuvre to Iran. One side effect of this is the intensively higher risk of new waves of refugees fleeing Syria (especially if government troops launch a ground offensive).

Russia has become and will remain an essential element of the game in the Middle East. However, there are no grounds to claim that it will move beyond the aspect of instigating and playing on instability in the region – neither the scale of the regional challenges nor the limited means Russia has at its disposal allow this. Besides, Russia has no real allies in this region. Furthermore it is still an open question as to what costs Russia will have to incur both directly in connection with the operation (financial and human expenses, the risk of fluctuations of the oil price, etc.), in relations with the players involved in the Middle Eastern game (Turkey, Saudi Arabia and others) and regarding security in Russia itself (the potential risk of terrorist attacks in the Russian Federation) and, last but not least, the potential costs linked to the possible deterioration of relations with the West.

Map

Russian air raids in Syria (September 30 - October 6)

Appendix 1

The targets of Russian air raids in Syria

Since 30 September, Russian forces have launched possibly hundreds of air strikes in the north-western provinces of Syria:

Latakia: places: Deir Hanna, Ghamam, and Jabal al-Akrad, targets: Jaish al-Fatah, Jabhat al Nusra and Ahrar ash-Sham, amongst others;

Idlib: places: Jisr ash-Shughur, Al Habit, Khan Sheykhun, Bailon, Ihsem, Maarat al-Numan, targets: Liwa Suqour al Jabal training camp, amongst others;

Hama: places: Kafr Zita, Al-Lataminah, Al-Salamiyah and Tlol al-Humur, targets: Tajammu al-Izzah command centre, amongst others;

Homs: places: Rastan, Talbiseh, Al Zafarana, Deir Foul, Ghanto, targets: Ahrar ash-Sham and Jabhat al-Nusra, amongst others.

The air strike targets included organisations linked to the Free Syrian Army (Liwa Suqour al Jabal and Tajammu al-Izzah) and Jabhat al-Nusra (Ahrar ash-Sham and Jaish al-Fatah).

Some targets (such as Al-Salamiyah and Tlol al-Humur) are located in the areas which are deemed to be controlled by the forces of Bashar al-Assad.

Additionally, three air strikes were launched on 2 and 5 October on areas controlled by Islamic State (Maadan Jadid and Cassert-Farrah in al-Raqqa province and As-Sukhnah in Homs province). However, it is not clear what the targets of the air strikes were.

Appendix 2

Non-governmental participants of the civil war in Syria

In addition to the troops which are loyal to the government in Damascus and the Iranian, Russian and Hezbollah forces supporting it, dozens of other military groupings are taking part in the Syrian civil war. Most of these are small organisations which depend on others and have a larger organisation as their patron. The latter include:

- The Free Syrian Army: it was set up in 2011 by deserters from the Syrian army. This is an organisation of the moderate anti-regime forces. It is supported and armed by the West (mainly the USA), Turkey, Israel and some Arab states (e.g. Jordan). It is linked to a number of smaller groupings, including Liwa Suqour al Jabal, Tajammu al-Izzah and the Islamic Front. It is in a bitter conflict with al-Assad’s troops and Islamic State, and has a tactical alliance with Jabhat al-Nusra. It controls areas in the provinces Aleppo, Idlib, Hama, Homs, Quneitra, Daraa and Al-Suwayda.

- Jabhat al-Nusra: a radical Sunni organisation, formally a Syrian branch of Al-Qaeda. It groups together Sunni radicals from Syria, the Arab states, Western European countries and the former USSR. It is linked to a number of smaller groups, including Ahrar ash-Sham, Jaish al-Fatah, Harakat Sham al-Islam, Jund al-Aqsa, Jaish al-Muhajireen wal Ansar, Junud al-Sham, etc. It is in bitter conflict with al-Assad’s troops and Islamic State, and has a tactical alliance with the Free Syrian Army. It controls areas in the provinces Latakia, Aleppo, Idlib, Hama, Homs, Quneitra, Daraa and Al-Suwayda.

- Islamic State: previously known as the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria/the Levant (ISIS/ISIL), a radical Sunni organisation, which used to be an Iraqi branch of Al-Qaeda, and at present is in conflict and rivalry with them. It is the strongest Islamic terrorist group in Syria and Iraq, and lays the foundations of statehood in the areas it takes control of. It is in conflict with all the parties to the Syrian conflict. Its militants from Syria, Iraq, Arab states, European countries and the former USSR and they should be counted in the tens of thousands. It controls areas in the Syrian provinces Deir ez-Zor, Al-Hasakah, al-Raqqa, Aleppo, the eastern part of Damascus and Homs provinces and a large part of western Iraq.

- Democratic Union Party (PYD): left-wing, secular and nationalist party of Syrian Kurds. It exercises autonomous authority in the areas of northern Syria inhabited by ethnic Kurds (Jazira, Kobane and Afrin cantons – the region known as Rojava). It has links with PKK and is recognised by Turkey as the party’s Syrian branch. It is supported by the USA in its struggle against Islamic State. It has taken a tactically neutral stance on the al-Assad regime.