Turkey and the EU: the play for a security zone in Syria

The military successes of Assad’s forces backed by the Russian Federation in northern Syria mark the beginning of a new phase in the Syrian crisis. One of the temporary effects of the offensive is the increasing number of refugees on the Turkish border (30,000 – 70,000 people) and the threat of another wave of migration from the Middle East to the EU in the short term (according to Turkish estimates, as many as 600,000 people may leave Syria in the worst-case scenario). In the extreme situation, a successful offensive could end the Syrian opposition’s resistance in the north of the country and, as a consequence, lead to a breakdown of the Turkish policy on Syria. The way the situation has recently developed in Syria complicates and intensifies the ongoing EU-Turkish dialogue on halting and resolving the migration crisis.

This became the subject of the unplanned visit which the German chancellor, Angela Merkel, paid to Turkey on 8 February and it will be discussed during the EU-Turkey summit scheduled for 18 February in Brussels. Ankara seems to be determined to force the EU to offer tangible political support for its policy: to stop and protect refugees while they are still in Syria; this would prevent their exodus and would also allow the opposition forces to remain effective in northern Syria. In practice, this is a return to the proposal to create a security zone in northern Syria, which Ankara has been pushing for without effect for years. For the EU, this would mean a serious step towards direct engagement in the Syrian conflict, something it has consistently avoided. The alternative for the EU would be a crisis in relations with Turkey and would include the threat of a huge wave of new refugees coming from both Syria and Turkey, and, in effect, the need to thoroughly revise its approach to Turkey and the region as a whole.

A new stage of the war in Syria

Assad’s army, with essential support from the Russian air force, has launched a decisive offensive in north-western Syria. The goals of this offensive are: to recapture Aleppo, to force back the threat against Latakia (the regime’s main bastion), and to defeat the opposition forces in this part of the country. One consequence of the offensive is the mass exodus of the civilian population, a major part of whom are heading towards the Turkish border, which places additional pressure on Ankara. The Turkish government has announced that it will allow the new wave of refugees to cross the border only should it prove to be absolutely necessary.

The regime’s military successes mean that it is more and more likely that it will recapture the territories that are currently controlled by the opposition forces supported by Turkey. At the same time, Syrian Kurd troops and Islamic State, both of which are hostile towards Ankara, have maintained their positions in northern Syria. If Assad’s troops manage to reach the Turkish border, this will mean the elimination of Ankara’s and the West’s proxies in this part of the country, and this will dramatically reduce Turkey’s real influence on the way the situation will develop in Syria itself. Furthermore, the offensive launched by the regime’s troops and the Russian air force proves that the peace talks in Geneva between the governmental delegation and the opposition backed by Turkey and its allies (Saudi Arabia and Qatar) are politically pointless. The negotiations have been suspended; if Assad’s successes continue, it cannot be ruled out that his gains will receive political acceptance.

Refugees, a shared problem

One specific and serious problem the EU and Turkey have in common linked to the Syrian war is the huge wave of refugees. According to the government in Ankara, around 2.7 million refugees and migrants are currently in Turkey (the vast majority of them are from Syria). Over one million people, including – according to incomplete Eurostat data – over 320,000 Syrians arrived in the EU (mainly Germany) – last year alone, most of them via Turkey. According to EU-Turkey agreements, Turkey undertook to co-operate in restricting the uncontrolled flow of refugees via its territory to the EU in exchange for financial aid (over 3 billion euros), the enhancement of political co-operation (including unfreezing accession negotiations and visa liberalisation), and a programme of controlled resettlement of refugees from Turkey to the EU. Progress in implementing the arrangements made last autumn will be evaluated by the European Commission in a special report which is due to be published on 10 February. The co-operation which has from the onset been focused on managing the existing crisis without the possibility of resolving it in principle, fails to meet the expectations of both parties. This will be an issue for discussion during the EU-Turkey summit on 18 February. The recent escalation of the crisis in Syria has significantly intensified the problem, and this was the reason for Chancellor Merkel’s unplanned visit to Turkey.

Turkey has been backed into a corner

The refugee issue is very important but is far from being Turkey’s only problem linked to Syria. The regime forces in Damascus, the fact that Russia openly supports Turkey’s enemy, Assad (Iran also does, but more discreetly), the Syrian Kurds and Islamic State are all considered to be fundamental threats to Turkey’s security and interests. The opposition forces (so-called ‘moderate Islamists’, Syrian Turkmens, etc.), unofficially supported by Turkey, are supposed to be the Turkish counterweight to all of these. Turkey views more decisive support for these forces as a way to strengthen the opposition and to secure its own interests, but also to ensure security to the civilian population in Syria. Turkey promotes the security zone project in northern Syria and needs support from the West to be able to create it – Turkey has never succeeded in doing this by itself, and now, given the open confrontation with Russia, its is even less likely to manage it. The West, unwilling to become engaged militarily in Syria, has disregarded Turkish appeals. The recent offensive by Assad and Russia in Syria poses the risk that the existing strongholds for Turkish policy in Syria will be liquidated and the conflict would principally be transferred to Turkish territory. One consequence of this would be that Syrian opposition fighters would permeate to Turkey and the EU (it is impossible to fully monitor them).Another consequence would be a significant strengthening of the Kurdish forces in Syria and thus also in Turkey. In both cases this concerns political and military forces linked to Kurdistan Workers’ Party, which is openly hostile towards Turkey.

Is Turkey making an offer the EU cannot refuse?

Turkey has shifted its previous policy and at the present phase of the refugee crisis it is principally blocking Syrian refugees access to its territory (it’s the EU has criticised it for this). It has instead been offering them support in the form of humanitarian aid across the border. In the short term, this allows it to prevent an increase in the number of refugees on its territory. In the broader perspective, this should convince the EU to direct humanitarian aid via Turkey to Syria, i.e. this would lead to an intensification of the European presence and activity in the direct hinterland of the military operation in Syria.

At the same time, Turkey is strongly emphasising the brutality of the Syrian-Russian offensive and points out to it as the direct cause of the present crisis; in this it has found understanding and support from Chancellor Merkel. The appeal that NATO should become engaged more actively in the refugee issue (for the time being, in the Aegean Sea region) has also met with understanding. In practice, this is a process of defining the zone of the humanitarian crisis in Syria – where both Turkey and the EU are active – which should ultimately and in a short time be transformed into a security zone (with the necessary no-fly zone and a possible ground operation, i.e. military engagement), protected from the offensive by Assad’s forces. Acting alone, Turkey is unable to cope with any of these elements and requires support and engagement from the West (the EU and the USA). The implementation of this project would mean, at least in part, the implementation of Turkey’s security zone project, which was rejected by the West as recently as during the negotiations last autumn. The alternative suggested semi-officially by Turkey would in fact be a withdrawal from co-operation with the EU and opening up the migration channel to Europe.

Possible developments

The conflict between the regime forces and the anti-Assad opposition appears to be entering the decisive military phase (the problems with Islamic State and the Kurds in Syria are still an open question). Therefore, existing problems linked to refugees and, for example, radicals from Syria permeating into Turkey and Europe, may intensify significantly.

The problems – for both Turkey and the EU – are consequences of the war in Syria (including refugees and terrorism) and they are becoming an ever greater political and social challenge, and the remedial measures taken fail to meet the needs and expectations of both Turkey and the EU. The Turkish response is to consistently return to the idea of a security zone while, as time goes by, the political costs of this solution are escalating, and the potential gains are dwindling. From Ankara’s point of view, the security zone issue is also becoming a key and decisive element of future Turkey-EU relations.

Given this context, more strategic significance is being attached to Turkey-EU dialogue in the coming weeks and above all the upcoming Turkey-EU summit in Brussels (18 February). The EU has failed to develop a strategic alternative to co-operation with Turkey to reduce the extent of the migration crisis, while this co-operation entails an increasing risk of engagement in the Syrian crisis (and, as a consequence, the risk of confrontation with Russia). If the EU’s and Turkey’s visions of the Middle Eastern problems diverge, this in turn would mean an ongoing erosion of co-operation on the strategic level, the risk of a spectacular escalation of the migration crisis and, in the broader context, the need to thoroughly revise the EU’s policy towards Turkey and the Middle East.

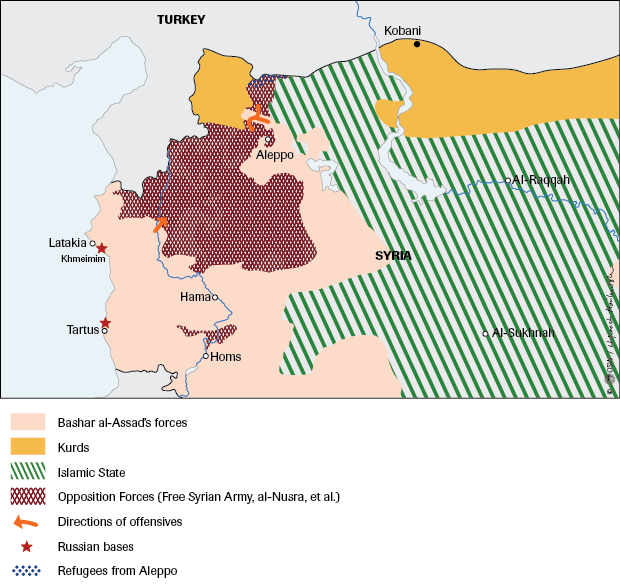

Map

Offensive by regime forces in north-western Syria. February 2016