Central Europe in the European Parliament elections

The elections to the European Parliament have weakened the Christian Democrats (EPP) and Social Democrats (S&D) in Central Europe; but although they have won fewer seats than five years ago, they still have an advantage over the other political groups. Meanwhile, the Conservatives (ECR) and the Liberals (ALDE) have increased their Central European representation in Parliament. These four main political groups took more than 90% of the seats allocated to the region. Far-right parties recorded a clear failure in the region (except Slovakia and Estonia), as did the Greens (except Lithuania and Latvia), in contrast to their good results at the pan-European level (see Annex).

The election results confirmed that the right has maintained its strong position in Central Europe; its representatives won in most countries of the region, albeit while giving way to political parties belonging to ALDE in individual countries. No social democratic parties won in the CEE countries. The changes on the political scene in Central Europe are largely in line with pan-European trends; however, the dynamics of this process in the region’s individual countries depend primarily on internal conditions. The European affiliation of the Central European parties only affects their national and European policies to a limited extent. Each party’s approach to the EU depends to a greater extent on how integrated the member state is into EU structures. In Bulgaria, Croatia and Romania, which remain outside the Schengen and euro areas, both the right and left repeat their demand to participate in these projects. However, in those countries that joined the EU in 2004, there were politicians from both ECR and EPP & ALDE demanding during the election campaign that the EU Council be strengthened in relation to the European Commission.

The election campaign

In almost all countries in the region, the election campaign – as in other EU countries – was dominated by national issues, due to the strong polarisation of the political scene which has been observed throughout almost all Central Europe. In most countries, the opposition parties sought to make the vote a referendum on how effective the work of their countries’ governments had been, including in lobbying for their national interests in the EU, with varying degrees of success. The topic of migration, which was mainly pushed by the far-right parties, was not raised much in the national debates. The exceptions were Estonia and Hungary; Prime Minister Viktor Orbán once again successfully mobilised his voters, presenting himself as a defender of Christian and national values against Brussels, which in his opinion is attempting to transform the EU’s member states into a multinational country of immigrants. However, he owes his success not only to his many years of anti-immigration campaigning, which resonates with the opinions of most Hungarians, but also to the fact that the opposition has limited access to media and advertising, as both areas are dominated by the Fidesz camp.

The election results of individual political forces

The European People’s Party

In Central Europe, the EPP gained a clear advantage over the Socialists, who came second. However, in most countries of the region, the Christian Democrats won fewer seats than they did five years ago, and the distance between them and the S&D has decreased. The EPP mainly lost votes to the ECR (including in Poland and the Czech Republic) and to an extent to ALDE (for example in Romania). The Christian Democratic parties in the region have very diverse electoral programmes, as reflected for example in their different attitudes to the Orbán government’s policy in Hungary. During last year’s vote to activate Article 7 of the Treaty on European Union (TEU) against Hungary, Fidesz could count on support from the majority of Bulgarian, Croat and Slovene EPP deputies, but not those from Romania, the Czech Republic or Poland. The decision in March to suspend Orbán’s party from membership of the EPP helped to relieve tension within the Christian Democrats’ ranks, but the question of Fidesz’s membership in the group remains open; Orbán cast his whole campaign in opposition to the ‘liberal elites in Brussels’, in which he includes the leading Christian Democrat politicians. Fidesz’s critics in the EPP will therefore seek to definitively expel the Hungarians from their ranks, the more so as the EPP will still be the largest political group in the EP even without Fidesz. According to political logic, however, the EPP’s poor result should encourage the Christian Democrats’ leaders to come to an agreement with Orbán. Similarly the Hungarian PM, seeing that the radical Eurosceptics have had only moderate success in Western Europe, may be more willing to make concessions to his Christian Democratic allies at the EU level. Alternatively Orbán could cooperate with the ECR, which was clearly weakened in these elections, or with the European Alliance of Peoples and Nations (EAPN), the foundation of which has been announced by Matteo Salvini and Marine le Pen.

The Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats

Like the EPP, the Social Democrats received fewer seats than they did five years ago. The Left did not win in any country in the region, and where it has ruled in coalition, it has usually suffered clear defeats: in the Czech Republic the ČSSD did not even pass the election threshold, coming behind the Communist Party; and the left-wing parties in Slovakia and Romania, which have been plagued by numerous scandals, fell to second place, losing seats in the European Parliament (in Romania, up to half of them). In the other countries of Central Europe, the social-democratic parties generally improved their results in comparison with previous European elections. The most seats in the EP from the region, however, were brought to the Social Democrats by the ruling PSD party in Romania – which, due to its reforms debilitating the system to combat corruption, has been suspended from membership of the Party of European Socialists. Compared to their Western counterparts, the social-democratic parties in Central Europe are generally more conservative, and sometimes (as in Slovakia and Romania) even present themselves as defenders of ‘traditional values’ in opposition to the liberals. The generational change in some countries of the region has encouraged leftist politicians to try and imitate the models of their Western European counterparts. However, the failure of the Social Democrats in Germany and the Socialists in France could discourage some of them from attempting any such mimicry. The failing attractiveness of the S&D’s example is demonstrated by the fact that the Hungarian Democratic Coalition, led by the former Socialist Prime Minister Ferenc Gyurcsány, is currently in talks about moving to the ALDE.

The European Conservatives and Reformists

The ECR has retained its position as the third political force in Central Europe. The majority of this group’s members will come from Central Europe, with a strong predominance of Polish MEPs. Compared to the elections five years ago, the ECR has also strengthened its position in Latvia and Slovakia and the Czech Republic, where the ODS, which is one of the group’s co-founders, confirmed its position as that country’s main opposition force by winning four seats. The ECR’s Central European character was strengthened by the decision before the election to put up a Czech, Jan Zahradil, in the competition for the post of President of the European Commission. Zahradil’s balanced, open-minded views have helped the Western media began to see a clearer distinction between the ECR and those groups which are actively seeking to dismantle the EU. The group’s final composition is not a foregone conclusion. On the one hand, the ECR is exposed to attempts by the EPP and the new Salvini/le Pen political group to drag some of its MEPs out of the ranks. On the other hand, it is still possible that the ECR will be joined by Fidesz, or the ideologically conservative Slovenian SDS and SLS, which are close to the Hungarian party.

The Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe

The liberals have improved their election result in Central Europe compared to 2014, thanks among other things to their ability to attract new anti-establishment forces to their ranks. Before the 2014 European Parliament elections, they were joined by the Czech ANO party, and in subsequent years they have entered into cooperation with the Romanian USR-PLUS coalition, the party of the Slovenian Prime Minister Marjan Šarec, and Progressive Slovakia. As part of the post-election realignment, negotiations on entering the ALDE Group have also been initiated by the Hungarian Democratic Coalition (currently in S&D), and the PRO România party could follow in its footsteps. These processes have resulted in the high heterogeneity of ALDE’s representation in the region. While the liberals from Slovakia, Slovenia and the Baltic states support the strengthening of European integration, the Czech ANO takes the opposite position. Before the election its leader, Andrej Babiš was campaigning under the slogan of a ‘tough and uncompromising’ defence of Czech interests in the EU. Due to its sovereignist rhetoric, and the so far unresolved suspicion between the Czech and EU authorities that Babiš’s company used EU subsidies illegally, there have been reports that the ANO might settle outside the new political group created by ALDE with Emmanuel Macron’s party. The Bulgarian DPS party was in a similar situation to ANO, as one of its mandates in the European Parliament was won by Delian Peevski, a controversial oligarch who dominates the Bulgarian media market, although he has since declared that he will renounce his seat.

Greens / European Free Alliance

One of the major differences between Central Europe and Western Europe is the Greens’ result in these elections. In the continent’s west, this political family has been considerably strengthened, mainly in Germany but also in France. However in Central Europe, the Greens only won seats in Lithuania (2) and Latvia (1). Most likely, this group will be also joined by the Czech Pirate Party, although it has been negotiating with ALDE as well. Apart from the Baltic states, the Green agenda was pushed into the background during the election campaign, despite the fact that the Greens were part of broader coalitions in several countries (for example with the right in the Czech Republic, and with the left in Hungary). Paradoxically, the Greens achieved a better result in the European elections five years ago, when deputies joined this political group from Croatia, Slovenia and Hungary as well as the Baltic states. Regardless of the Greens’ weak position in Central Europe, the policies of this group will affect the whole of the EU in the new parliamentary term. In their search for support among younger voters in Western Europe, the main European parties willingly drew upon the Greens’ demands during the last campaign, which proves how effective they have been in influencing public debate, particularly in Germany. The Greens have increased their potential to promote debates on climate protection initiatives within the EU, but as they do not have any representatives on the European Council, the forum of the European Parliament will probably remain their main field of activity. EU institutions are expected to become much more active in the field of climate policy, which will likely resonate on the political scene in Central Europe, especially as drought and air quality are being debated increasingly frequently within the region.

The extreme right and left parties

Compared to Western Europe, the extremes of right and left received little support in Central Europe. The far right only achieved a very good election result in Slovakia, where the People’s Party-Our Slovakia (ĽSNS) of Marian Kotleba won 12% (2 seats in the European Parliament), and in Estonia, where EKRE gained almost 13% (1 seat). Kotleba’s success is largely attributable to that country’s low turnout (23%, the lowest in the EU) and the Slovak anti-system forces’ great capacity to turn their supporters out in elections. The ĽSNS’s members are likely to remain outside the structures of the established political groups as unaffiliated, like the only deputy from Hungary’s Jobbik. Despite the efforts of Matteo Salvini and Marine le Pen, who personally supported politicians close to them in Prague, Bratislava and Tallinn, the ranks of their new political group will only be joined by two deputies from the Czech SPD, and possibly by individual MPs from Croatia and Estonia. For comparison, in 2014 the extreme right in the elections won 11 seats. The Czech Communists also did worse than five years ago, and are still the only Central European party to sit with the European United Left and Nordic Green Left grouping. Croatia’s anti-system, syncretic Živi Zid party, which cooperates with the Italian Five Star Movement, also won one seat. However, the small number of seats for the extreme right and left parties does not mean that these groups have lost their importance on the region’s political scene; radical groups have attracted considerable electorates in Bulgaria, Croatia and Slovenia, and have a good chance of crossing the electoral thresholds in elections to their national parliaments.

in cooperation with Ryszarda Formuszewicz

Annex

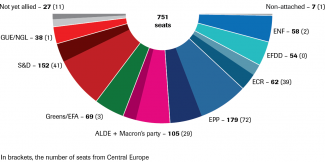

Graph. The mandates of Central European countries in political groups after the 2019 elections to the European Parliament

Source: Website of the European Parliament, ‘European election results in 2019’, and https://election-results.eu/ own calculations, as at 29.05.2019

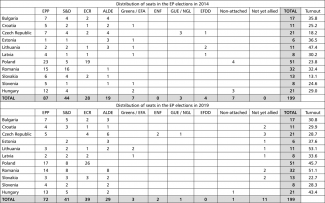

Comparison of the results of elections to the European Parliament in 2014 and 2019

Source: Website of the European Parliament, ‘European election results in 2019’, and https://election-results.eu/ and own calculations, as at 29.05.2019