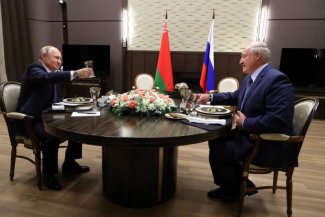

The failure of the Russian-Belarusian summit

Presidents Vladimir Putin and Alyaksandr Lukashenka met on 7 December in Sochi, Russia. They spent five hours discussing issues linked to the integration of the two countries. It had been announced that the talks would end in the signing of an agreement on closer integration . This was planned for Sunday, 8 December, on the 20th anniversary of the founding of the Union State of Russia and Belarus. Special working commissions and prime ministers representing the two countries have been engaged in negotiations concerning this issue for several months. The document entitled ‘Action Programme for Belarus and the Russian Federation to implement the provisions of the agreement on setting up the Union State’ was intended to contain general arrangements concerning enhancing integration, while its details and schedule were to be provided in attachments to the agreement in the form of 31 ‘road maps’. The content of all the documents is classified. It is only known that they concern various economic sectors and social issues that are vital for the co-operation of the two countries, but do not address political issues (for more details, see Appendix).

The package of documents was not signed at the agreed time. On 7 December, presidential talks were held instead of the planned formal session of the Council of Presidents of the Union State. There was no press conference at the conclusion of the talks. Only a brief announcement for the media was made by the chairman of the Russian section of the negotiation commission, Minister of Economic Development Maxim Oreshkin. He announced that the parties’ stances had become significantly closer and that another meeting of the two heads of state would take place on 20 December 2019 in Saint Petersburg. The Belarusian feedback on the negotiations was presented by Uladzimir Siamashka, the country’s ambassador in Moscow, who said that the negotiations were moderately positive and announced that the two countries had coordinated their stances on the electric energy sector and common customs control system. He also added that reaching a compromise as regards oil and gas supplies is still the most serious challenge. Contrary to expectations, there were no celebrations on the anniversary of the founding of the Union State, on 8 December. The presidents only exchanged brief greetings that were made known to the general public. The Belarusian opposition led people to the streets in Minsk on 7 and 8 December to protest against integration with Russia. These mere not massive demonstrations; between several hundred and one thousand people participated in them. Even though the government did not grant consent to the demonstrations, the law enforcement agencies did not intervene.

The integration of the two countries as part of the Union State, which was established under the treaty signed on 8 December 1999, was suspended for many years. Last December it was resumed on Russia’s initiative, when Prime Minister Dmitri Medvedev issued an ultimatum, making further subsidising of the Belarusian economy dependent on Minsk’s engagement in fulfilling its commitments. Towards the end of 2018, the Belarusian government, under Russian pressure, agreed to establish working groups to develop a plan for enhancing integration. On 6 September, the prime ministers of both countries initialled a draft Action Programme for Belarus and the Russian Federation to implement the provisions of the agreement on setting up the Union State. It was also announced at that time that the agreements on enhancing integration, including the 31 road maps, would be finalised by early December this year.

Commentary

- The fact that no new integration agreement with Belarus, or even a single document of at least symbolic value, was signed during the Sochi summit should be viewed as a failure for Russia since it wanted this act to be signed on the 20th anniversary of the Union State. This was intended to demonstrate real progress in integration of the two states being pushed through by Moscow., This is important for Russia for both internal political and external reasons. On the one hand, this was expected to contribute to improving president Putin’s image at home, including temporarily ahead of the annual teleconference with journalists scheduled by the Kremlin for 19 December. On the other hand, Russia wanted to show other countries (mainly those from Western Europe) that it remains the dominant state in the post-Soviet area and is able to build its own effective structures as a counterweight to Western integration structures, especially the European Union. Signing an agreement with Belarus at the planned time would also have strengthened the image of Russia and Putin before the Normandy Format summit (the meeting of Russian, Ukrainian, German and French leaders to discuss the conflict in Donbass) on 9 December.

- The Russian-Belarusian talks will be continued. However, there are doubts as to whether the next meeting on 20 December will lead to a breakthrough and the agreements being signed in the form as planned by Moscow. In a situation where anniversaries and the temporary political calendar no longer strengthen Belarus’s negotiating position, Moscow, exasperated by Belarusian resistance, may take a tougher stance and even again resort to economic and energy pressure by imposing restrictions on Belarusian goods and cutting oil and gas supplies. This is even more likely given the fact that the Kremlin has been making efforts over the past few years to reduce the costs of co-operation with Minsk partly due to economic stagnation in Russia and partly because Moscow is losing its patience with Lukashenka’s policy of equivocation. The Russian side is aware of the significance of the subsidies offered to Belarus. The changes in Russian fiscal policy planned for 2019–2024 will completely deprive Belarus of the preferential oil prices offered to it by Russia so far. In effect, the Belarusian economy may sustain a loss of almost US$1 billion in 2020, and the total cost of the changes in the coming five years, according to Minsk’s estimates, may range between US$6 and 10 billion. The price of Russian gas is the key factor that decides on Belarus’s economic condition. At present, Minsk pays US$127 per 1,000 m3 of natural gas, i.e. double the rate for Smolensk oblast, which reduces the competitiveness of Belarusian producers versus the Russian ones. Belarus’s situation is additionally complicated by the fact that the tariffs for next year and onwards have not been determined. In an extreme case this may mean that there will be no grounds for continuing gas supplies after 1 January 2020.

- Lukashenka has emphasised his support for the idea of the two countries’ integration. Proof of this includes his signature under the agreement setting up the Union State of Russia and Belarus. The top priority granted in Belarus’s policy to relations with Russia as an ally is not only an effect of the ideology of the Belarusian regime based partly on Slavic unity and brotherhood between Russians and Belarusians. Minsk, declaring its will to develop close co-operation with Russia, is also attempting to obtain a guarantee that it will continue to receive Russian subsidies in the coming years. It also insists on being offered the same prices for oil and gas as those paid by Russian entities. At the same time, fearing to lose independence, Lukashenka has consistently staved off real integration processes for years, hoping that positive rhetoric and symbolic gestures will be enough to satisfy Moscow’s ambitions. Belarus also believes that its strategic location makes it a precious military ally for the Kremlin and a transit corridor for Russian goods and raw materials and that it should receive support from Russia for this reason alone. Lukashenka is stalling. While he has agreed to enter into negotiations, even under intensified pressure from Moscow, he does not in fact intend to give up the attributes of sovereignty during the negotiations. It also worth noting that the thesis that the integration of the two countries should be taking place ‘on equal terms’ is nothing but a rhetorical ploy which provides grounds for blocking negotiations in case Russia pushes through solutions that are contrary to Belarusian interests. Therefore, it seems that the failure of the Sochi talks was mainly Lukashenka’s fault, as he saw stalling as his sole chance for defending his stance and hope for negotiating favourable terms of economic co-operation and preferential prices of oil and gas supplies in the coming years.

- Russia is applying increasing pressure on Minsk. The pressure may further intensify ahead of the parliamentary election in Russia (September 2021) and the 30th anniversary of the collapse of the USSR (December 2021). By that time, the Kremlin wants to achieve a visible political and propaganda success as regards enhancing integration with Belarus. In the longer term, this will most likely have an impact on decisions concerning Putin’s political future after 2024 (when his last constitutionally permitted term as the president will have expired). This is especially true given the fact that one of its variants, which has been speculated about for a long time in Russia, envisions that Putin will lead the Union State of Russia and Belarus.

Appendix. Belarus’s economic dependence on Russia and the plans for enhancing the integration of the two countries

The economic relations between Russia and Belarus are quite asymmetrical. There is a big difference between the economic potentials of these two countries. In 2018, Belarus’s GDP was equivalent to around 3.4% of Russia’s GDP, and Russian support for the Belarusian economy, according to estimates, accounted for around 10% of Belarus’s GDP. Russia is also Minsk’s main creditor. At present, Belarus’s debt to Russia is worth around US$7.8 billion. In addition to this, Minsk borrowed an additional approximately US$2.7 billion from the Eurasian Fund for Stabilisation and Development which was established on the basis of Russian funds. Belarus also received an export loan worth US$9.5 billion from Russia to be allocated for building the Astravets nuclear power plant. In effect, Russia accounts for 75% of Belarus’s foreign debt. The Russian Federation is also the main investor in this country (around 40% of Foreign Direct Investments) and the leading trade partner (Russia accounts for around 50% of Belarus’s trade).

The Russian daily Kommersant has managed to receive information about the Action Programme for Belarus and the Russian Federation. According to the newspaper, in order to implement the provisions of the agreement on setting up the Union State, the process of enhancing Russian-Belarusian integration should begin in 2020 and end in January 2021. There are plans to introduce a common fiscal code and civil code and to further harmonise the rules of foreign economic co-operation, macroeconomic policy, currency control and industrial, agricultural, trade and transport policies, to create a common institution of an oil, gas and electric energy market regulator or the integration of bank supervision (however, two central banks will remain in operation). Minsk and Moscow are not currently planning to introduce a common currency and a single currency issuing authority. They do, however, envisage the unification of social policy, introducing similar principles of social support and ‘equal rights’ for citizens of both countries in the future. The document does not mention such issues as defence, security, the courts, law and order, education, science or healthcare. It also should be emphasised that Kommersant’s information is a media publication, and the content of the negotiated agreements is kept secret, which makes it difficult to fully evaluate both sides’ intentions.