A new stage of the conflict over Nagorno-Karabakh

Azerbaijani and Armenian forces have been engaged in intense clashes since the morning of 27 September. The clashes have been seen along the entire line of contact that separates Azerbaijan-controlled areas from the separatist Nagorno-Karabakh Republic (NKR, a para-state without international recognition that in practice has close links with Armenia on many levels). The Azerbaijani forces managed to seize a few towns and, most likely, a strategic hill in the Murovdag range (Azerbaijani Murovdağ, the northern section of the contact line). Both sides claim they have inflicted severe losses on their opponent in terms of personnel and matériel, but these data cannot be verified as there is an information blockade. Furthermore, access to the region is practically impossible (and this is not solely because of the pandemic). Mobilisation was announced in Armenia and the NKR (and partly in Azerbaijan, where reservists were drafted). Martial law was declared in both countries and in the NRK. The international community, including the UN and the OSCE Minsk Group established to settle the Karabakh conflict (co-chaired by France, Russia and the USA), has appealed for fighting to be stopped and talks resumed. Moscow is conducting intensive telephone consultations ‒ President Vladimir Putin talked to the Prime Minister of Armenia, Nikol Pashinyan (upon Pashinyan’s request), and the Russian Minister of Foreign Affairs, Sergei Lavrov, talked to his counterparts in Armenia, Azerbaijan and Turkey.

Commentary

- The present fighting is the heaviest since the ceasefire that ended the Nagorno-Karabakh war (May 1994). Since then, the conflict has been regarded as frozen, but in practice it was not. There were regular exchanges of fire (including outside Karabakh itself, along the Armenian-Azerbaijani border) and fatalities were reported. The absence of peacekeeping forces that would have separated the positions of the two parties contributed to that. The so-called ‘four-day war’ broke out in 2016 which ended after Russia's mediation (as a result of this war, the line of contact was slightly adjusted in favour of Azerbaijan). The border between Armenia and Azerbaijan was the scene of intense clashes which lasted for a few days in July this year. The Azerbaijani side suffered greater losses then. However, never before have the parties involved announced a mobilisation or proclaimed martial law.

- The current escalation was most likely initiated by Azerbaijan (Baku calls this operation ‘counter-strike’ and claims that it was launched in response to provocations from the NKR; Yerevan has reported a massive attack on Armenian positions and emphasises that civilians are also falling victim to it). For the first time since the war of the 1990s, targets in the capital of the NKR, Stepanakert (Azerbaijani Khankendi, Xankəndi) came under artillery fire. The Armenian side confirmed the deaths of 31 soldiers from Nagorno-Karabakh and two civilians, and released information about the shooting down of several helicopters and dozens of enemy drones, as well as the neutralisation of more then ten tanks and combat vehicles. The Azerbaijani side reported several fatalities among civilians and the destruction of several Armenian Osa anti-aircraft systems and over 20 tanks, as well as the shooting down of more than ten drones. Due to disinformation from both parties, these data should be treated as rough estimates. The scale of the operation and the equipment used (including the extensive use of aviation, especially drones) suggests that Baku's goal is to achieve a significant military success. The maximum extent of this would see it conquering the entire NKR area, and the lower limit of its aims would be to conquer at least part of the ‘occupied territories’, and then force the Armenian side to accept the new state of affairs (de iure the entire disputed area would belong to Azerbaijan).

- After the clashes that took place in July this year, violent and spontaneous pro-war demonstrations took place in Baku. Reportedly, up to tens of thousands of people took to the streets. The demonstrators also attempted to break into the parliament building. In addition, young men came en masse to the conscription commissions, wanting to fight for Nagorno-Karabakh. The Azerbaijani government is concerned about mass public movements – especially after the events in Belarus – and is trying to channel them. A military success would undoubtedly strengthen the position of the ruling elite and President Ilham Aliyev personally, and would earn him additional legitimacy. In turn, a possible failure or setbacks – like those seen over two months ago – pose a real threat to him. For this reason, if initial failures occur on the war front, Baku will most likely strive to end the operation as soon as possible. A defeat would also seriously weaken the government in Yerevan: failure in the 2016 four day war accelerated the erosion of the then power elite and facilitated the victory of the revolution and Pashinyan’s rise to power two years later.

- Moscow remains the main arbiter in the Karabakh conflict, but has limited its activity to consultations for now, without taking more decisive steps to end the fighting. It is possible that its aim is to weaken the position of Nikol Pashinyan, who came to power as a result of street protests. Although he declares a close alliance with Russia, he is not fully trusted by the Kremlin. However, Moscow cannot allow Armenia to be defeated, because a defeat of its ally would mean a loss of credibility. Moscow also wants to maintain its influence in Azerbaijan (to which it sells weapons, for example) and to prevent the growth of Turkey’s influence in this country. Turkey is unequivocally supporting Baku in the conflict, and the way it is doing so (firm declarations at the highest level, ostentatiously close military co-operation) may indicate that it wants to break the Russian monopoly on security in the South Caucasus. This would mean the region may become the next arena, after Syria and Libya, where the turbulent relations between Moscow and Ankara will be manifested. Regardless of these calculations, Moscow remains the main external actor capable of influencing the course of events around Nagorno-Karabakh. This is also what the West seems to expect of it and it has limited itself to verbal appeals for peace, as it has no will or instruments to pursue an active policy in this region.

- There are many indications that even if there was no strategic breakthrough in the conflict and if the intensity of the fighting decreased, it would not be permanent. The negotiations are de facto frozen (the last talks between Aliyev and Pashinyan took place in March 2019, the last meeting was in February this year, on the occasion of the Munich Security Conference). The roused public expectations are enormous, and the Russian-Turkish rivalry is an advanced process.

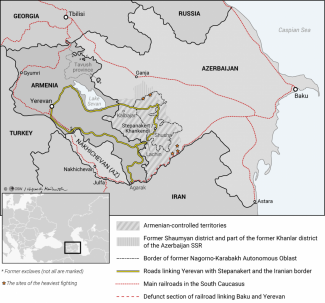

Map. Armenia and Azerbaijan. The area affected by the conflict over Nagorno-Karabakh (28 September 2020)