The war in Nagorno-Karabakh: more and more going Azerbaijan’s way

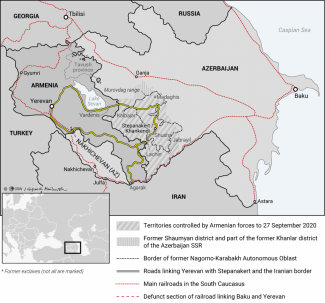

The fighting in Nagorno-Karabakh, which started with the Azerbaijani offensive on 27 September and over the following days has taken the form of positional warfare (artillery and rocket fire, with heavy use of aircraft and drones), has intensified in the last several hours, accompanied by an exacerbation of the political situation (the tone of statements and the mutual accusations have become harsher). Azerbaijani forces have launched another land operation, taking control of several more localities, probably including Madaghiz in the northeast and Jabrayil in the southeast of the conflict zone (see Map). The Armenian side has denied these losses, although Azerbaijan’s President Ilham Aliyev has confirmed them. Azerbaijani forces have continued shelling targets in Nagorno-Karabakh, including its capital; Armenian forces, for their part, have fired on towns in Azerbaijan, including Ganja, the largest city in the western part of the country.

Commentary

- The initiative in the conflict remains with Azerbaijan, which started the operation a week ago in response (as the official line runs) to Armenian provocations. Aliyev’s recent statements have mentioned the “restoration of historical justice”, and comments in Azerbaijan have also spoken of a legitimate resort to military means, since the peace process – which has now lasted over a quarter of a century – has brought no progress (the area occupied by the separatist Armenian Republic of Nagorno-Karabakh is de jure part of Azerbaijan). Of the most recent probable territorial conquests, Jabrayil, which is the local district seat, is of more importance. It should be noted, however, that most of the captured towns – it is possible that some have changed sides, or will soon do so – lie within the so-called occupied territories beyond Karabakh itself, i.e. the former Soviet Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Oblast (NKAO). As a result of the war in 1992–94, Armenian forces took control of almost the entire NKAO and the lands around it, which are considered to be a buffer zone. The exchanges of fire have not yet led to large-scale human or material losses, and they are intended to harass and demoralise the other side. Baku’s tactics have put the Armenian side on the defensive and are depleting its resources, which are much more modest than those of Azerbaijan. Armenia’s shelling of Ganja should be seen as a show of determination and desperation. It is unclear whether the towns in Azerbaijani have come under attack from Armenia itself (which Yerevan denies) or from Nagorno-Karabakh, which claims it has the right to do so as part of its ‘war against terrorism’.

- Azerbaijan, which is being politically supported by Turkey (although the direct participation of its army in the operation remains unconfirmed), will continue its offensive in order to gain the greatest advantage and capture the largest possible area. The gains it has probably made so far would certainly not satisfy Azerbaijani society or meet its heightened expectations. It should be assumed that Azerbaijani forces will halt their offensive if they encounter effective resistance or decisive Russian intervention. In these cases, President Aliyev’s position would be strengthened, and the halt to the attack would be justified to the public in terms of international pressure. Such a development would also have to be accepted by Ankara, which would come into direct confrontation with Moscow if it contested any such move on Russia’s part. Regardless of when the operation comes to a halt, however, it should be considered highly likely that Azerbaijan (with considerable assistance from Turkey) would have changed the status quo around Karabakh in its favour as a result of the present escalation.

- The threat to the security of Karabakh itself (the area of the former NKAO) is perceived by the Armenian side as existential, and they treat it as equivalent to a threat to Armenia and the Armenians as a nation. In this regard, Yerevan expects to see some involvement from Moscow (which has so far maintained considerable restraint), as well as the fulfilment of its obligations, both bilaterally and within the framework of the Collective Security Treaty Organisation (although formally these obligations do not include Nagorno-Karabakh). The fact that Moscow has refrained from any decisive reaction stems from its desire to minimise the costs associated with any form of intervention (including political costs) and to obtain the greatest possible benefit from any such move – which is not guaranteed, but might become necessary to maintain its credibility and prestige. The aim of a possible intervention would be to maintain – and ideally, to strengthen – Moscow’s control over the region. To achieve this goal, it may be necessary to send Russian peacekeepers into the conflict area, perhaps under the aegis of the CIS, which would in practice ensure the security of Karabakh (both Baku and Yerevan have opposed any such move in previous years).

- Moreover, Moscow’s plans probably include resolving some of the more immediate issues, including putting the Armenian leader Nikol Pashinyan in his place (his position would be threatened if Armenia suffered a genuine defeat and underwent territorial losses, and because of his country’s deteriorating economic situation). Moscow could also intervene in the form of an ultimatum sent to both parties if Azerbaijani forces threatened to capture the capital city of Stepanakert (Azerbaijani: Khankendi, Xankəndi). It is also possible (although less likely) that a Russian contingent would be introduced into the fighting area earlier, perhaps in formal response to attacks on targets in Armenia by Azerbaijan or Turkey. In that case, Moscow would probably want to send its forces by the shortest overland route, i.e. through Georgian territory. However, Tbilisi has not as yet granted permission for military transit over its territory to either Armenia or Azerbaijan.

Map. Armenia and Azerbaijan. The area of Nagorno-Karabakh conflict (5 October 2020)