It is official: Germany abandons nuclear energy

15 April 2023 saw the shutdown of Germany’s three remaining nuclear power plants. This marks the end of Germany’s move away from using this type of energy, which was triggered in 2002 and confirmed in a decision taken in 2011. The policy of Atomausstieg (nuclear phase-out) has remained unchanged in the face of both Germany’s (and the EU’s) increasingly ambitious climate agenda and the energy crisis caused by Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine. The only adjustment which the Olaf Scholz government has introduced, following a sharp dispute within the coalition which lasted many months, was the postponement of the deadline to shut down the remaining reactors from the end of 2022 to mid-April 2023 (for more see ‘Germany: Nuclear power phase-out postponed for three and a half months’).

The FDP, which is the smallest coalition member, and the opposition CDU/CSU proposed that the operation of these power plants should be extended until mid-2024. Numerous experts, representatives of the business sector and the majority of Germans (according to most polls) were in favour of extending the use of nuclear power at least until the end of the present crisis. Bavaria’s Prime Minister Markus Söder (CSU) has been particularly active in this field. He has readily referred to the pro-nuclear public sentiment and has been using this issue in the campaign ahead of the upcoming elections to the Bavarian Landtag (state parliament). However, neither the Greens not the SPD are ready to accept more profound changes, as these parties’ electorate is dominated by opponents of nuclear energy (the Greens’ voter base includes the most vehement critics of nuclear energy).

The history of German nuclear energy: from euphoria to hysteria

In West Germany, the nuclear energy era began in 1955, when the federal ministry for nuclear energy was established to supervise research and the construction of the first test reactors. In 1961, electricity generated in a nuclear power plant was fed into the grid for the first time. The following years saw a rapid development of this technology: over the next two-plus decades a new nuclear power plant was launched almost every year. Altogether, alongside small, test and prototype reactors, 30 reactors were built in West Germany and 6 in the GDR (see Appendix). In the 1990s, they accounted for 30% of electricity generated nationwide.

Initially, the German public was enthusiastic about nuclear energy, believing that the construction of more reactors would meet the dynamically developing economy’s demand for clean and cheap energy. It was assumed that the share of nuclear energy in the energy mix would reach as much as 50%. In the 1970s, however, critics of nuclear energy began to gain ground in the public debate. They criticised this technology by arguing that it was ‘highly dangerous’ to the environment. Another controversial issue involved the storage of radioactive waste (a problem which remains unresolved in Germany until this day). Moreover, many observers saw a connection between the use of nuclear energy and nuclear weapons. Increasingly frequent protests held by opponents of nuclear energy often ended in clashes between the demonstrators and the police. Some of these clashes were particularly violent, for example the one in Brokdorf in 1976. The anti-nuclear movement began to attract representatives of many different social groups, from students to farmers. Finally, in 1980 it was transformed into a political party, the Greens, which soon gained public support in the state elections and in 1983 its representatives won several seats in the Bundestag for the first time. Opposition to nuclear energy continues to be the ideological foundation of this party and an important element in the lifetime achievements of many of its leading politicians.

Following the Chornobyl disaster in 1986, anti-nuclear slogans entered the mainstream of the political debate for good: they were adopted by the entire left wing of Germany’s political spectrum, with the SPD as its main component. When the Social Democrats and Greens came to power in 1998, the proposal to abandon nuclear energy was included in the coalition agreement. In 2000, the German government reached an agreement with the energy sector regarding the gradual phase-out of nuclear energy (the so-called nuclear consensus), and in 2002 the Bundestag officially adopted a law reflecting this agreement, with the coalition parties voting in favour. The law allocated energy quotas to specific power plants, and plans were made to shut them down once they had met these quotas. It was assumed that the last remaining nuclear plant would be shut down at the beginning of the 2020s. When the coalition made up of the CDU/CSU and the FDP, parties which supported nuclear energy, took power in 2009, a decision was made to postpone the nuclear phase-out until the 2030s; in autumn 2010, the coalition adopted the relevant law in the Bundestag.

However, an event happened soon after this which triggered a political and social transformation in public attitudes. Following the Fukushima disaster, which happened in Japan in March 2011, German public debate began to be dominated by discussions, partly irrational, on the safety of nuclear energy, and anti-nuclear sentiment surged. Polls conducted at that time showed that 75% of Germans demanded that the government abandon this technology as soon as possible. In this situation, facing a rapid increase in the level of support for the Greens and the risk of losing the upcoming elections in Baden-Württemberg, which were of crucial importance to the CDU/CSU, Angela Merkel’s government decided to do an about-turn and join the anti-nuclear camp. With votes from all parties, the Bundestag passed a law introducing a requirement to shut down 8 out the 17 reactors operating at that time by the end of the year, and to gradually shut down the remainder by the end of 2022. This was when Germany’s energy transition to renewable energy sources, which had been ongoing for many years, began to be referred to as the Energiewende, which literally means an ‘energy turning point’.

The consequences of the nuclear phase-out

As in previous years, the shutdown of the last remaining nuclear power plants will have consequences for the German electricity generation system. Firstly the decommissioning (in a short period of time) of units with a total capacity of 4.3 GW which operate at the base of the system will entail increased electricity generation, mainly at coal-fired power plants, but also in the gas-fired power plants which complement the increasingly intensive generation of electricity from renewable sources. This effect was recorded during previous shutdowns, especially post-2011 (see The leader is gasping for breath. Germany’s climate policy).

Secondly, in the mid-term, the role of natural gas as a backup fuel in a system which is increasingly based on RES will grow, provided that the gradual phase-out of coal-fired power plants in line with the current law is carried out (for more see Germany bids farewell to coal. The next stage of the Energiewende). Due to the phase-out of a large number of nuclear and coal-fired power plants, the German system will need several tens of new gas-fired units: estimates indicate that units with a capacity of 17 to 25 GW will need to be built by 2030 (the total capacity of the currently working gas-fired power plants is 33 GW). According to Berlin’s plans, the construction of these units will need to take into account the option of switching them to hydrogen over the next decade.

Thirdly, the above-mentioned replacement of electricity generation at low-emission nuclear power plants with generation at high-emission coal-fired power plants (and at somewhat ‘cleaner’ gas-fired units) will raise the greenhouse gas emissions generated by the energy sector. This contrasts with both Germany’s declared climate policy goals and its global image as a leader in the fight against global warming. This inconsistency clearly undermines Berlin’s credibility in this field; and in the context of the present energy crisis and of Germany’s and the EU’s ambitious climate policy goals, the shutdown of the last remaining nuclear power plants has come under criticism from Berlin’s foreign partners. It is worth noting that Germany’s Atomausstieg policy is also having negative consequences for the European integrated electricity generation system.

Fourthly, the shutdown of three large nuclear power plants which operated at the base of the system will increase Germany’s demand for electricity imports from the neighbouring countries. Moreover, all the available scenarios indicate that as a result of the (almost) simultaneous phase-out of coal-fired units in the mid-2020s Germany will transform from an electricity exporter into a net electricity importer. Even more striking, as regards electricity imports Germany is particularly dependent on France, which generates 75% of its electricity in nuclear power plants. The German Atomausstieg would not be possible without the wide availability of electricity produced in France. It was due to the repeated malfunction of French reactors in 2022 and a rapid drop in electricity imports from France that Berlin decided to prolong the operation of its three remaining nuclear power plants. They were intended to serve as a back-up option in the electricity generation system at the height of the winter season.

Finally, most German analyses indicate that the nuclear phase-out will negatively affect wholesale electricity prices. This is because the cheaper electricity generated in nuclear power plants will be replaced with much more expensive electricity produced in coal- and gas-fired units. The magnitude of the expected price increase is unclear. It should be noted that this trend will not be confined to Germany, and will affect Germany’s neighbours alike.

The (not so) total phase-out

The shutdown of Germany’s remaining nuclear power plants does not equate to a definite end of the nuclear sector in Germany. Nor does it mean that the issue of nuclear energy will disappear from German public debate. The law on Atomausstieg does not cover the uranium enrichment facilities in Gronau or the Lingen-based facility which manufactures nuclear fuel rods (which is controlled by the French Framatome company). They will continue to operate in the coming years, and will deliver their products to nuclear power plants in France, Belgium and the United Kingdom. Opponents of nuclear energy have recently targeted these companies, demanding that they should be closed down. Moreover, German universities plan to continue to educate nuclear technology engineers and carry out research on new technologies, in particular on nuclear fusion. Efforts to determine the final location of a radioactive waste repository will continue to be a heated topic in the German public debate for many years to come. Recent developments suggest that the painstaking process of selecting the location has once again been delayed, which means that used nuclear fuel will continue to be stored in provisional storage facilities for many decades (for more, see ‘Tainted by Gorleben. The issue of radioactive waste storage in Germany’). Moreover, the process of dismantling the decommissioned power plants will take at least fifteen years.

APPENDIX

Table. List of German nuclear power plants

Acronyms: PWR – pressurised water reactor; BWR – boiled water reactor; HTR – high-temperature reactor; HWGCR – heavy water gas-cooled reactor; PHWR – pressurised heavy water reactor; SNR – sodium-cooled nuclear reactor.

Source: Federal Office for the Safety of Nuclear Waste Management (BASE).

Map. Location of German nuclear power plants

Source: Federal Ministry for the Environment, Nature Conservation, Nuclear Safety and Consumer Protection.

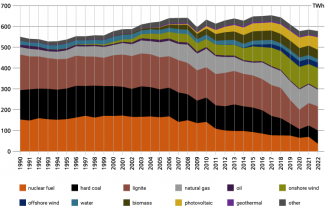

Chart. Electricity production in Germany in 1990–2022

Sources: Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Climate Action, AGEB.