Another war or a deal? A new phase in the Azerbaijani-Armenian conflict

On 13 October, the media reported that US Secretary of State Antony Blinken had informed members of the House of Representatives earlier this month that an Azerbaijani attack on southern Armenia was highly likely. A spokesperson for the State Department denied these reports, but also stressed that the US strongly supports Armenia’s sovereignty and territorial integrity, and that any violation of these would lead to serious consequences. Blinken allegedly briefed a group of House members after the exodus of the Armenian population from Nagorno-Karabakh to Armenia, which followed the successful Azerbaijani military operation (see ‘Exodus of Armenians from Nagorno-Karabakh’). In a conversation with President of the European Council Charles Michel on 7 October, Azerbaijan’s president Ilham Aliyev said that eight Azerbaijani villages were still “under Armenian occupation” and should be liberated. Another round of peace talks between Aliyev and Armenia’s prime minister Nikol Pashinyan is due to take place in Brussels later this month. Their two previously scheduled meetings, in Granada and Bishkek, did not materialise.

On 15 October, President Aliyev travelled to Nagorno-Karabakh and for the first time visited Khankendi (Xankəndi, Armenian: Stepanakert), the region’s main city and the former capital of the unrecognised Republic of Nagorno-Karabakh.

Commentary

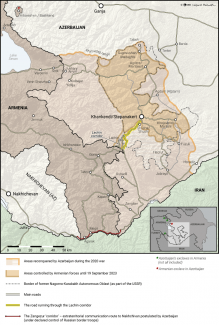

- By visiting Khankendi/Stepanakert on the 20th anniversary of his presidency, Aliyev symbolically closed the book on the Karabakh phase of the Azerbaijani-Armenian conflict, which ended as Azerbaijan expected, and on its terms. At stake in this new phase is the settlement and future shape of relations between the two countries. Azerbaijan wants to persuade Armenia to join the network of regional transport corridors that includes the routes and has the status that the Azerbaijani government desires. Opening the so-called Zangezur corridor that runs through Armenian territory is crucial in this regard, as this would strengthen the regional Azerbaijani-Turkish duopoly, which already has considerable influence in Georgia (see ‘The (pan-)Turkic Caucasus. The Baku-Ankara alliance and its regional importance’). Such a scenario would strip Armenia of a part of its sovereignty, so from its point of view it is crucial to retain control over the future transit routes.

- The eight villages that Aliyev mentioned are located within five Azerbaijani exclaves in Armenia, which the Armenian forces occupied in the early 1990s (Azerbaijani forces captured Armenia’s only exclave in Azerbaijan at that time). The parties to the conflict have not raised this issue before. The escalation of Azerbaijan’s demands reflects its confrontational stance and determination to force a weakened Armenia to make further concessions. As part of this tactic, Azerbaijani politicians, led by the president, have also demanded that former Azerbaijani refugees be allowed to return to Armenia (some 185,000 Azerbaijanis fled Armenia in the late 1980s and early 1990s). However, the most important thing for Azerbaijan is to open and take control of the land connection (which is in practice an extraterritorial corridor) that runs through Armenia to Nakhichevan and then on to Turkey. If no agreement is reached on this so-called Zangezur corridor in the coming weeks (roughly by the end of 2023), Azerbaijan will probably try to seize territories in southern Armenia by force, despite the threat of international sanctions; in January Aliyev said that the ‘corridor’ would be opened “whether Armenia wants it or not”. The likelihood of this scenario coming to pass would increase further if Pashinyan was removed from power. Any new Armenian leader would certainly be much less willing to engage in dialogue with Azerbaijan (the Armenian opposition has accused Pashinyan of betraying national interests) and could receive significant support from Russia. In this situation, Azerbaijan would probably take action to establish facts on the ground.

- It appears that the US is factoring in the possibility of an Azerbaijani attack on Armenia. This is evidenced by remarks that a spokesman for the US State Department, Matthew Miller, made to the Armenian news agency, which included a warning of “serious consequences” in case of any violation of Armenia’s territorial integrity. Should such an attack occur, the US government could reinstate the 907th Amendment to the Freedom Support Act, which bans the provision of non-humanitarian aid to Azerbaijan. The Congress passed it in 1992 after Azerbaijan announced its blockade of Armenia. Since 2002, the US president has suspended the amendment every year for a further 12 months, but formally it remains in force to this day. In this situation, a decision not to suspend the amendment would cast a serious chill over Azerbaijani-US relations.

- The presence of an EU observer mission on Armenia’s border with Azerbaijan since the start of 2023, and the determination of France, which has for years acted as an advocate of the Armenian question, would raise the political cost of any attack by Azerbaijan on Armenia. France’s past gestures of support for Armenia have included the French Senate’s resolution that called for the recognition of Nagorno-Karabakh’s independence after the Second Karabakh War. France has now increased its aid to Armenia, and announced that it will open a military attaché’s office in Yerevan and a consulate in Zangezur/Syunik in southern Armenia; Iran already has a diplomatic post there, while Russia is also planning to open its own mission. Azerbaijan has sharply criticised these moves as being aimed at continuing the conflict. Meanwhile, the most promising path forward for the peace process is the so-called Brussels format, wherein the European Union is the least controversial and most trusted potential ‘broker’ (see ‘Competing peace formats. Russia and the EU’s attitudes towards the Armenian-Azerbaijani conflict’). However, Armenia and Azerbaijan are unlikely to reach an agreement and sign a peace treaty without the participation of or approval from Turkey (should this happen, normalisation of relations between Armenia and Turkey would follow). This is evidenced by the sequence of events surrounding the planned meeting between Aliyev and Pashinyan in Granada on the margins of the European Political Community Summit on 5 October. French President Emmanuel Macron did not invite Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan to join the meeting (which German Chancellor Olaf Scholz also attended), and then Aliyev refused to come to Spain, citing France’s biased stance.

- The position of Russia has now weakened considerably, after having acted for years as the most important intermediary in the peace process, negotiated the ceasefire in the Second Karabakh War in 2020, and then served as the protector of the unrecognised Republic of Nagorno-Karabakh. Pashinyan did not attend the CIS summit in Bishkek on 13 October, where he was expected to meet Aliyev. The main reason for this was the crisis in Armenian-Russian relations (see ‘A serious crisis in Armenian-Russian relations’) as well as Armenia’s lack of trust in Russia as a mediator. Even though it has been difficult for Russia to impose its own agenda, it has retained a number of tools in Armenia (a military base, the presence of FSB border troops, significant economic assets) and a potential for destabilising the country, which largely results from its influence with the Armenian opposition. Despite its involvement in Ukraine and the resulting reduction of its activities in other regions, the Kremlin appears determined to keep Armenia within its orbit. It is therefore conceivable that it could support an attempt to oust Pashinyan, who has questioned his country’s allied relationship with Russia and declared a desire to forge closer ties with the West. For this reason, we can expect that in the event of an Azerbaijani attack, Russia will not support Armenia as long as Pashinyan remains in power, despite its commitments to its allies.

Map. Area of the Azerbaijani-Armenian conflict

Source: the authors’ own research.