The EU approves financial assistance for Ukraine and negotiates military assistance

At an extraordinary summit held on 1 February in Brussels, the European Council (hereafter the Council) decided to launch the Ukraine Facility, an instrument intended to provide financial assistance to Kyiv in the period from 2024 to 2027. The decision was made as part of the EU budget revision, and required the approval of all 27 member states – including Hungary, which had expressed its veto at the previous summit back in December. In the situation of prolonged political deadlock in the US over providing assistance to Kyiv (see ‘A bleak future for Ukraine aid in Washington?’), the launch of this facility is of key importance for the stability of Ukraine’s public finances.

At the same time, the EU member states have failed to reach an agreement as regards the continued funding of EU military assistance for Ukraine and the establishment of a separate fund for this purpose under the European Peace Facility. Negotiations between the member states on the amount of funds and the terms & conditions for disbursing them are ongoing. France is seeking to increase the number of orders placed with European armaments companies, while Germany would like to reduce its involvement. The negotiations are expected to end at the beginning of March.

Financial assistance is urgently needed

The Ukraine Facility will be launched as part of the process of revising the EU’s multiannual financial framework, and is intended to provide stable and foreseeable assistance to Ukraine worth €50 bn in 2024–27. This support is of key importance to Ukraine’s state budget. According to Kyiv’s estimates, it will need to obtain $37.3 bn in assistance to maintain financial stability in 2024 alone. In 2023 it received $42.4 bn, which included $19.5 provided by the EU. The facility envisages that Ukraine will receive €9.75 bn annually to support its state budget. However, Kyiv is seeking to have this sum raised to €18 bn as early as the first year of the facility’s operation. It would also like to receive a payout of €4.5 bn by the end of March.

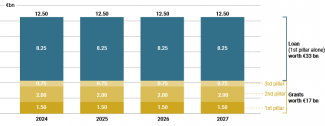

The Ukraine Facility, which is expected to serve as the EU’s main instrument of its financial assistance to Kyiv, has three pillars. The first, worth €39 bn (of which €33 bn are low-interest loans and €6 bn are grants), is intended to support the financial stability of the Ukrainian state. The second (€8 bn in grants) includes financial instruments to attract and launch public & private investment as part of Ukraine’s reconstruction. The third (€3 bn in grants) will fund technical assistance, including support for Ukrainian local governments and civil society. The funds offered under the first pillar will be disbursed in line with the Ukraine Plan devised by Kyiv and the European Commission (EC). It sets out the objectives, the timeframe and the mechanisms for monitoring the implementation of the planned activities, which the EC will carry out on a quarterly basis. Disbursement of the subsequent instalments will depend on the results of this monitoring. If it transpires that these funds were spent in violation of the rules, the EC will be allowed to request the Council to withhold support until the conditions are met, or to suspend the assistance altogether. However, the European Council will decide to withhold or continue funding by qualified majority voting, in order to circumvent a possible veto by Budapest.

In the future, interests accrued on the frozen assets of the Central Bank of the Russian Federation (which, according to estimates, may amount to around €3–5 bn annually) could serve as an additional source of funds which will be offered as a non-repayable subsidy under the Ukraine Facility. The Council has approved this concept, although it emphasised that the final decision would require the EU to adopt the relevant legislation.

Hungary’s solitary stance

The establishment of the Ukraine Facility became possible when Hungary withdrew its veto on the issue. Prime Minister Viktor Orbán’s opposition at the December summit had forced the European Council to convene the extraordinary meeting on 1 February. Despite pressure from Budapest, the EU member states rejected the proposal to carry out an annual assessment of the utilisation of funds, which would require the Council’s unanimous approval, as this could enable Hungary to veto further instalments of aid. Instead, it was agreed that an annual debate on the utilisation of the funds would be held on the basis of a report compiled by the EC. In addition, the Council will be allowed to ask the EC to prepare a request for the facility’s review on the basis of the next revision of the EU budget. This indicates that unanimity will be required to amend the programme, but not to extend it.

Orbán has presented the outcomes of the summit as a success for his negotiating acumen, although in effect he failed to push through his initial demands, and his stance was isolated in the EU forum. Even Slovakia’s prime minister Robert Fico, who has been an ally of Orbán in the disputes over the rule of law (see ‘The Fico–Orbán meeting: an Article-7 alliance’), strongly supported the establishment of the facility. In addition, had Orbán resorted to using a veto, the EU’s ‘plan B’ envisaged the remaining 26 countries adopting a support package in an extra-budgetary procedure. In this situation, Hungary would have risked becoming marginalised. Similarly, Budapest could not have counted on many further concessions in its dispute with the EU institutions over funding: Ursula von der Leyen has been under pressure from the European Parliament, which contested the December decision to unlock around a third of the frozen funds earmarked for Hungary. When the EC released €10.2 bn in cohesion funds immediately ahead of the December summit, the payment of the remaining funds (€11.5 bn from the cohesion funds and €10.4 bn from the National Recovery Plan) was made conditional on Hungary meeting certain requirements, which is unlikely in the immediate future.

The importance of the pressure brought by the largest EU member states should not be underestimated. Aside from French president Emmanuel Macron and German Chancellor Olaf Scholz, Italy’s prime minister Giorgia Meloni played a key part in exerting this pressure. In addition to a joint meeting between these three politicians and Orbán (which the presidents of the EC and the Council also attended) ahead of the summit, in recent weeks the Italian prime minister has also held a series of talks with her Hungarian counterpart. It is believed that Meloni views a change in Budapest’s policy towards Ukraine as precondition of Fidesz joining the European Conservatives & Reformists Group in the European Parliament (where at present Orbán’s party remains unaffiliated).

The negotiations on military aid

During its meeting the European Council failed to decide on the amount and conditions of the EU’s future funding of military aid for Kyiv. The Council of the European Union will make this decision by the beginning of March. Thus far, the EU has provided aid to Ukraine on the basis of its extra-budgetary European Peace Facility (EPF, see ‘An EU War Chest: the success and uncertain future of the European Peace Facility’), from which compensation was paid out to specific member states for the military equipment and ammunition they provided to Ukraine. So far, €10.5 bn have been allocated from the EPF to the member states according to the prices valid in 2018, or around €12 bn according to the current prices. Compensation for aid to Ukraine under this sum has reached €5.6 billion.

Negotiations on the establishment of a separate Ukraine Assistance Fund as part of the EPF are ongoing. Initially, Josep Borrell, the EU High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, proposed €20 bn to be allocated to this fund over four years. However, due to resistance from some states, the current proposed amount of funding is €5 bn with no timeframe. In addition, the terms and conditions of future assistance are also being discussed. France supports the view that the fund should encourage the member states to place joint orders for military equipment with European armaments companies. Germany, for its part, would like bilateral assistance to be taken into account when calculating the specific state’s contribution to the fund. So far, the EPF’s contribution calculation has been based on GDP, and Germany has been the biggest payer. Other states, such as Hungary, are making their consent to the establishment of the new fund conditional on the EU relieving them from the obligation to contribute to it. Moreover, Budapest has been blocking the launch of the eighth instalment of aid for Ukraine from the EPF worth €500 million since May 2023.

Aside from allocating funds for military assistance, last year the member states decided, under an EC proposal, to fund the purchase by 31 March 2024 of one million 155-mm artillery shells for Ukraine from the EPF under the ASAP programme (see ‘ASAP: EU support for ammunition production in member states’). However, only 520,000 shells will be produced by the end of next month (so far Ukraine has received 300,000); this information was shared during an informal meeting of EU defence ministers on 30–31 January. The most important outcome of this event involved the member states’ consent to train another 20,000 Ukrainian soldiers “by the end of summer”. Since the beginning of Russia’s full-scale war, almost 40,000 Ukrainian servicemen have been trained as part of the European Union’s EUMAM Ukraine mission, mainly in Germany and Poland.

Chart. Distribution of funds under the Ukraine Facility

Source: European Commission.