The imperative of cooperation: the European Commission’s strategy for the defence industry

On 5 March, the European Commission and the EU High Representative for Foreign and Security Policy unveiled the European Defence Industrial Strategy (EDIS), together with a draft regulation entitled the European Defence Industry Programme (EDIP). Their objective is to strengthen the European Defence Technological and Industrial Base (EDTIB) by increasing the pace of arms production in EU countries, removing obstacles in gaining access to raw materials, streamlining manufacturing chains, and in particular encouraging the EU’s member states to develop joint defence projects and make joint purchases. Another important aspect of these plans is an effort to involve the Ukrainian defence sector in cooperation with companies from the EU. From the EU institutions’ point of view these documents are ground-breaking: they mark the highpoint of the Commission’s efforts during its current term of office to provide comprehensive support from the EU for arms production, from the R&D phase to the joint use of equipment. However, the effectiveness of the EDIS and the EDIP will depend on the member states’ willingness to employ the newly created instruments.

The strategy: more cooperation within the EU, fewer purchases from third countries

Security and defence policy remains within the exclusive competence of the member states, but the Commission has been increasingly trying to exert influence on it, especially with regard to the defence industry, where it has competences in the area of industrial policy. These efforts clearly accelerated after Russia launched its full-scale invasion of Ukraine, as reflected by the Act in Support of Ammunition Production (ASAP, see ‘ASAP: EU support for ammunition production in member states’) and the European Defence Industry Reinforcement through Common Procurement Act (EDIRPA), both adopted in 2023. According to the Commission, the European defence industry has the potential and knowhow to compete with the US, the global leader in this field, but it has lagged far behind due to its fragmentation, uncoordinated production and procurement (only 18% of joint purchases in 2021), the member states’ over-reliance on equipment produced outside the EU (78% of purchases in 2022–23) and a level of military spending that is still much lower in the EU than in the US: in 2023, the EU’s member states allocated a total of €270 billion to defence, while the US committed $816.7 billion.

The Commission’s strategy for the defence industry is intended to provide the EU countries with a perspective on how to improve this situation, and to set non-binding targets. Some of these goals have been put forward before, such as the minimum threshold of 35% for joint procurement that was set in 2007. Although the member states have managed to reach only half of this target, EDIS has now raised it to hit 40% by 2030. The other two targets are equally ambitious: firstly, the value of intra-EU trade in arms and military equipment should reach 35% of the market’s total value by the end of this decade (companies are expected to derive more profits than today from selling their products to EU countries than from exporting them outside the EU); secondly, half of the budget for the modernisation of the armed forces should go to European defence companies (60% by 2035).

While encouraging the member states to raise their defence spending, the Commission is also setting up instruments to coordinate and agree on priority purchases, offering financial incentives for joint ventures and even providing a source of knowledge about the weapons and military equipment manufactured within the EU, as lack of awareness of their existence is thought to have influenced decisions to make purchases abroad. According to this vision, European industry should respond more efficiently to the surge in demand generated by the Russian invasion of Ukraine and focus on its core capabilities, such as drones. The strategy also says that the EU will encourage the financial market to be bolder in supporting the arms industry. The European Investment Bank may also take steps in this direction. In addition, the strategy calls for building partnerships, and attaches special importance to gradually involving Ukraine in EU defence cooperation, including through EDIP programmes. An important issue, though one that may be controversial with regard to complementarity with NATO, involves strengthening the interoperability and interchangeability of defence capabilities. The document points out that the member states have an excessive tendency to detail their requirements in the process of procuring and certifying equipment to suit specific bidders. In the view of the EDIS’s authors, the standardisation framework agreements that have been developed within NATO (STANAG) are insufficient to overcome this problem; they will therefore be complemented with the European Defence Agency’s Standard Reference System (EDSTAR).

The regulation: mechanisms to support the industry

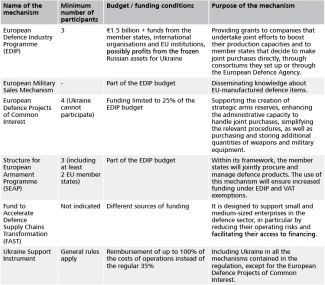

The EDIP is both the draft regulation to create the instruments described in the strategy and the name of the main mechanism contained in this regulation. The other instruments include the European Projects of Common Interest, the European Military Sales Mechanism, the Structure for European Armament Programme (SEAP), and the Fund to Accelerate Defence Supply Chains Transformation (FAST).

The Commission wants the EDIP-related legislative process to be completed by the middle of next year, when the ASAP expires. The EDIP is an extended continuation of the EDIRPA, an instrument which provides incentives for joint purchases of equipment and will expire at the end of 2025. The EDIP is also a temporary solution: it is designed to secure funding to support the arms industry in the period after both the ASAP and the EDIRPA expire, and before the new budgetary perspective comes into force in 2028. Hence the limited funding of €1.5 billion, an amount that could be reduced further under pressure from the Council of the EU. However, the Commission hopes that if the instruments it has unveiled prove effective, this will encourage the European Parliament and the member states to fund future defence cooperation programmes more generously under the new multiannual budgetary perspective. The EDIP also provides for the option to use the proceeds generated by the frozen Russian assets, but only for projects to support Ukraine and its defence sector.

The purpose of the EDIP is to provide grants to companies that engage in joint efforts to strengthen their manufacturing capacities, and to those member states that decide to make joint purchases through their national procurement agencies, consortiums they set up, or the European Defence Agency. Access to the EDIP is restricted to companies based in the EU or the European Economic Area. Exceptions can be made for companies from third countries which can guarantee that they are not subject to restrictions on the use and export of the weapons they produce. The catalogue of activities eligible for funding is extensive and includes joint procurement, enhancing manufacturing capabilities, ‘ever-warm’ facilities, production, sales, testing, certification and joint use of equipment. The regulation also introduces a number of mechanisms aimed at disseminating knowledge about arms production in the EU, facilitating defence cooperation between the member states (including through the creation of consortiums), and increasing access to financing for small and medium-sized enterprises in the defence sector (see Appendix).

The EDIP also provides for a range of emergency solutions, including allowing the Commission to order a company to perform a priority contract at the request of a member state. Previously, attempts had been made to include these provisions in the draft ASAP, but the Council of the EU rejected those ideas. The EDIP also features an institution intended to coordinate its implementation: the Defence Industrial Readiness Board, which will consist of representatives of the Commission, the High Representative for Foreign and Security Policy, the European Defence Agency, the member states and the associated countries.

The outlook

The EDIS and the EDIP are, first and foremost, strong political signals to the member states, defence companies and the banking sector. They demonstrate that arms production has become a priority in view of the increasingly difficult and unpredictable international situation. However, the effectiveness of the new instruments will depend to a great extent on the member states’ political will and ability to cooperate with one another. The inclusion of Ukraine in most of the EDIP mechanisms is meant to confirm the Commission’s determination to gradually integrate this country into the EU in selected sectors, as well as its desire to draw on Ukraine’s experience in certain areas, such as the production of drones. If successful, this programme may have implications for the funding of similar mechanisms under the future budgetary perspective. Small and medium-sized enterprises may be particularly interested in using EDIP as this creates an opportunity for them to establish cooperation with international partners.

The sum of €1.5 billion that is envisaged in the draft regulation may be considered disappointingly small. However, it is set to cover a two-year period, and reflects the pilot nature of the programme. The entire legislative act will be the subject of long-lasting negotiations in the incoming Parliament and the Council of the EU. The member states will probably push for a reduction of its budget and some of the coordination competences that the Commission has granted itself in it.

The main risk is that the EU institutions may create excessive expectations for the solutions proposed, partly as a result of the EDIS’s unrealistic targets for the member states’ cooperation and the procurement of European defence products. While such cooperation is desirable from the point of view of the interests of European defence companies, individual countries will also be guided by their political and military imperatives, such as delivery times, interoperability and enhancing their alliances with the US and the UK. In the current situation, the Commission should first of all work to boost production and facilitate access to defence products; the promotion of cooperation and ‘Buy European’ should be a secondary priority. Another missed opportunity is the fact that the EDIS does not include the target of raising defence spending to at least 2% of GDP, and that the EDIP fails to provide for appropriate bonuses for those countries that do so.

APPENDIX

Table. Mechanisms contained in the draft regulation on the European Defence Industry Programme (EDIP)

Source: the author’s own compilation.