The new US supplemental bill on Ukraine and the threat to confiscate Russian assets

On 23 April, the US Senate adopted a set of bills that had already been passed by the House of Representatives, which includes military and budgetary support for Ukraine; a day later, President Joe Biden signed it into law. The Ukraine-related legislation amounts to about $61 billion, including more than $21.5 billion in direct short- and medium-term military assistance for Kyiv as well as a $7.85 billion loan for budgetary support. This is the first authorisation for more US aid to Ukraine that Congress has passed since December 2022.

The new bill will allow the US to provide significant support to the Ukrainian war effort in the coming months, thanks to which the situation on the battlefield is likely to stabilise. Congress is not expected to approve any more aid for Ukraine before the next Congress and President alike are sworn in next January. The final vote tally on the legislation showed that the Republican Party (GOP) was sharply divided on whether to provide further assistance to Ukraine. This state of affairs will in all probability persist, and may even deepen.

At the same time, Congress passed three other bills: on support for Israel, on enhancing the posture of the US and its allies in the Indo-Pacific region, and on sanctions against Iran and Russia. The lattermost makes it possible to confiscate the Russian financial assets that the US had frozen as part of the Western sanctions and transfer them to Ukraine. However, it does not mean that such a decision will actually be taken; this will depend on whether a number of vaguely defined conditions are met. As such, the bill primarily amounts to a statement of political will and a way of putting pressure on the US’s allies.

A bumpy road for US assistance to Ukraine

It took almost eight months for Congress to pass a legislation securing US aid to Ukraine. Back in August 2023, the White House submitted the first request on that matter to Congress (for more see ‘Another aid package for Ukraine: a test for bipartisan support in the US’), followed by another one in October 2023. The first addressed the needs for emergency funding related to the war in Ukraine that were expected to arise in the first quarter of fiscal year 2024 (FY24, which started on 1 October 2023), while the other one covered the entire fiscal year and was paired with measures to protect the US border with Mexico (see ‘A bleak future for Ukraine aid in Washington?’), which was a priority for the Republicans. Based on the latter proposal, the Senate drafted a bill that combined support for Ukraine with aid to Israel and measures to strengthen deterrence in the Indo-Pacific region, which the upper chamber passed in February. However, neither proposal was considered by the House of Representatives.

The bill to support Ukraine stalled in the House mainly due to resistance from the GOP’s right wing, clustered around a conservative faction of more than 40 lawmakers (the so-called Freedom Caucus), which blocked the first draft in the autumn when the Republicans had a fragile majority of 222 seats in the 435-member House. Another contributing factor was the ouster of then House Speaker Kevin McCarthy and the subsequent election of Mike Johnson as his successor in October 2023. With the GOP’s backing, Johnson insisted that he would only agree to hold a vote on the bill to support Ukraine if lawmakers passed several pieces of legislation that would benefit the Republicans, including bills on protecting the US-Mexico border protection and immigration reform, as well as the federal budget for FY24. However, when a bipartisan group of Senate members submitted a compromise proposal on the border and immigration in February, the House Republicans rejected it as unsatisfactory.

As a way out of the impasse, in April Johnson introduced four bills: on support for Ukraine, on aid to Israel, on measures to strengthen deterrence in the Indo-Pacific and on sanctions targeting countries such as Iran and Russia. The House of Representatives approved all of these on 20 April. Johnson finally put the bills to a vote in the House for a number of reasons; he had been biding his time until he could take this step with the minimum risk of losing his position.

Moreover, if Russia breaks through the Ukrainian defences, the failure to approve US assistance to Ukraine could prove costly for Donald Trump and the Republicans ahead of the November elections; Trump himself had expressed his tacit approval for advancing the bill. Johnson himself was also coming under mounting pressure, both internally from ‘traditional’ Republicans and externally from the European allies. In addition, he may well have been influenced by US intelligence reports that the Ukrainian armed forces were in dire straits.

More than half of the House Republicans voted against the bill to support Ukraine (112 against, 101 in favour), although the Democrats supported it unanimously. The 40-plus group of far-right Republicans was joined by more than 70 more moderate ones. In the Senate, 48 Democrats and 31 Republicans voted in favour of the bill, while three Democrats and 15 Republicans opposed it. GOP lawmakers, particularly in the House, have increasingly taken into consideration the extreme positions of the Freedom Caucus members and their heavy presence in the conservative media, as well as the views of the party’s electorate, which is increasingly opposed to any interventionist foreign policy and expects the government to focus on domestic issues.

Another important factor is that Donald Trump, who is effectively the leader of the Republican Party, has been lukewarm towards Ukraine and has failed to express his unequivocal support for this country. The prospects for adopting another package of assistance to Ukraine remain uncertain, and it is unlikely to happen before the next president is sworn in January 2025. Since it is currently impossible to predict what political configuration will emerge after the elections, the chances for US aid in the next year are difficult to assess at this point.

The breakdown of the new support bill

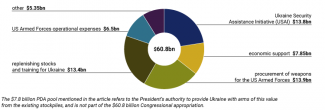

The bill includes both military and budgetary support for Ukraine, among other things; the total value of the legislation is $61 billion. The military support primarily includes the Presidential Drawdown Authority (PDA) to provide Ukraine with $7.8 billion worth of weapons and military equipment from the Department of Defense (DoD) stockpiles in the short term, and with weapons worth about $13.8 billion to be procured from the industry under the Ukraine Security Assistance Initiative (USAI) in the medium to long term.

In addition, the bill allocates about $13.9 billion to purchasing weapons for the US Armed Forces; about $13.4 billion to various other purposes (mainly replenishing the DoD’s stockpiles and training Ukrainian troops); and more than $6.5 billion to cover the operational costs of the US Armed Forces in Europe which have been incurred as a result of their response to the Russian invasion of Ukraine (see Chart).

One of the bill’s sections obliges the president to transfer ATACMS ballistic missiles to Ukraine as soon as practicable, without specifying their version. At the same time, it gives him the right to withhold such a transfer should he determine that doing so would be detrimental to the national security interests of the US. Ukraine had already received an older version of ATACMS (M39) with a shorter range of 165 km, while the newer ones can strike targets up to 300 km away.

Ukraine is expected to receive the first shipment of arms very soon; according to media reports, some of the ammunition has already been stored in various European countries, including Poland. Another of the bill’s provisions requires the administration to submit a multi-year strategy to Congress regarding US support for Ukraine that should establish specific and achievable objectives as well as define and prioritise US national security interests, on the assumption that it should be aimed at hastening Ukraine’s victory against Russia’s invasion forces.

In addition to the military assistance, Ukraine will receive economic support in the form of a loan of around $7.85 billion. The US President will enter into an arrangement with the government of Ukraine relating to the repayment of its economic assistance. He has the right to first cancel 50% of the loan and then the remaining part within specified periods. This form of support is a nod to those Republicans who have demanded greater fiscal responsibility and have been averse to any steps that would increase the US national debt.

Congress’s long-awaited passage of this legislation has been greeted with enthusiasm in Ukraine. President Volodymyr Zelensky has expressed his gratitude to President Biden, his administration and Speaker Johnson. He has specifically mentioned the transfer of ATACMS ballistic missiles, suggesting that Ukraine will receive the longer-range version.

The US threat to confiscate Russian assets

The adopted set of bills also includes legislation containing provisions on the confiscation of Russian assets (the REPO for Ukrainians Act). This will require the US President to work towards creating an international mechanism with US participation to confiscate the Central Bank of the Russian Federation’s reserves (c. $300 billion) that have been frozen as part of the Western sanctions, and to transfer them to Ukraine. It will not be possible to unlock the US-frozen funds (c. $4–5 billion) until the Russian-Ukrainian conflict comes to an end and Ukraine receives compensation for the damage caused.

The president has been granted the power (but is not obliged to use it) to announce the confiscation of some or all of the assets (both capital and interest) which are under US jurisdiction. These will be redirected to the Ukraine Support Fund that has been established specifically for this purpose; and will then be used to aid the country’s reconstruction and provide humanitarian & economic assistance. The bill also envisages the possibility of establishing the Ukraine Compensation Fund, an international body which could be supplied by both the funds confiscated in the US and the Russian assets seized in other countries. The fund is designed to serve as a pool for compensation payments to Ukraine under an international compensation mechanism established through cooperation between the US, the G7 countries, the EU, Australia and other partners.

The bill contains a number of ambiguities, but it will likely prevent Russia from recovering its US-controlled assets. The clauses that provide for transparency in this process suggest that the funds confiscated may be used to benefit Ukraine over an unspecified time horizon, due to the need to develop a procedural framework.

The bill stipulates that prior to the confiscation, the US will undertake to coordinate its actions with the leaders of the G7 countries, although the degree of this cooperation is not specified. The provisions on the need to cooperate with foreign partners show that the US wants this process to include those Western countries that have so far been stalling on confiscation. Indeed, the document’s wording confirms this: it stresses that other Western countries are holding the majority of Russian assets and explicitly mentions Belgium, where Russia has deposited some $190 billion. In this way, the US is trying to portray the bill as a mechanism that can be implemented by the West as a whole; this would increase its effectiveness without undermining the competitiveness of the G7 countries’ markets vis-à-vis one another.

Chart. Allocation of funds under the Ukraine supplemental bill passed by Congress in April 2024

Source: The United States Congress.