Problematic diversification. Turkey’s gas agreement with Turkmenistan

On 11 February, Turkey’s Minister of Energy and Natural Resources, Alparslan Bayraktar, announced the signing of an agreement between the state-controlled energy company BOTAŞ and Turkmenistan’s Türkmengaz. Under this swap contract, Türkmengaz will deliver up to 2 bcm of natural gas annually to Turkey. The supplies will be transported to northern Iran, and Turkey will receive an equivalent amount via the Iran-Turkey pipeline. Deliveries are set to commence on 1 March, with a planned volume of 1.3 bcm to be supplied by the end of this year. Details regarding the contract’s duration, the price of gas, and the specific terms of the deal with Iran were not disclosed.

Although the agreement covers a relatively small volume of gas, it aligns with the strategic interests of both parties. For Ankara, it represents another step towards diversifying its energy imports. For Ashgabat, it expands export routes for its key resource, particularly in light of the non-renewal of its gas sales contract with Russia and increasing competition from Moscow as a pipeline gas supplier to China. In 2024, Turkmenistan supplied China with approximately 32.5–33.5 bcm of gas, while Russia delivered 31 bcm. However, recurring disruptions in Iran’s energy deliveries and the potential impact of US sanctions on Iran’s energy sector may jeopardise the successful implementation of the deal. These challenges, combined with the lack of additional infrastructure, will hinder Turkmenistan’s ability to become a major gas supplier to the Turkish market and, in the longer term, the transit of Turkmen gas to Europe.

Commentary

- The contract holds major political significance as a pilot initiative for broader gas cooperation between the two countries. While it does not grant Turkmen gas with access to the European market – since Turkey will use the fuel for its own needs – it underscores Ankara’s key role in Ashgabat’s strategic plans. Turkmenistan, a major gas producer with reserves accounting for 8% of global supplies, has sought to export its resources to the West. The agreement with Turkey aims to strengthen Ashgabat’s efforts, revived after the Kremlin’s decision to halt gas supplies to the EU, to signal its readiness to supply Turkmen gas to the EU market. Additionally, the deal could help secure Azerbaijan’s approval for trilateral energy projects.

- The agreement aligns with Ankara’s ambition to serve as a key transit hub for regional gas exporters. Although the initial volume of gas sourced from Turkmenistan will be negligible in the short term compared to Turkey’s total imports (which in 2023 exceeded 50 bcm), a potential increase to 15 bcm annually within two decades, as suggested by Turkish officials, would be a significant development. However, achieving this goal would require new infrastructure, such as the launch of a Trans-Caspian pipeline across the Caspian Sea between Turkmenistan and Azerbaijan. This project has been obstructed by Russia and Azerbaijan, with the latter viewing Turkmen gas as direct competition.

- The signing of the agreement represents another step in Turkey’s efforts to diversify its gas supply sources ahead of forthcoming negotiations on extending its energy cooperation with Russia (see ‘Strength in LNG? The gas market in Turkey’). This pertains to two contracts for gas transit via the Blue Stream (16 bcm annually) and TurkStream (5.75 bcm annually) pipelines, both of which are set to expire at the end of 2025. Ankara’s ability to reach an agreement with Ashgabat – as well as the potential for expanding cooperation in the future – could serve as leverage in its negotiations with Moscow to secure more favourable gas supply terms. The agreement with Turkmenistan may also influence Turkey’s talks with Iran. The gas contract with Iran is among the most costly for Turkey, covering annual deliveries of 9.6 bcm and due to expire in July 2026.

- Transit through Iran will present a major challenge to Turkmen-Turkish gas cooperation. This is due to both technical limitations of Iran’s gas infrastructure and the risk of US sanctions. Iran’s pipelines are outdated and prone to failures, while periodic drops in domestic gas production – especially during increased local demand – frequently result in interruptions to gas supplies to Turkey. This renders the swap agreement between Ankara, Ashgabat, and Tehran susceptible to similar disruptions. Additionally, the Trump administration could impose further sanctions on Iranian energy exports. Should this occur, gas deliveries from Turkmenistan to Turkey via Iran would also be subject to restrictions. While both countries would likely seek exemptions, the process could be protracted and fraught with uncertainty.

- For Turkmenistan, the importance of the agreement lies in the diversification of its gas exports, which constitute the backbone of the country’s economy. Turkmenistan remains heavily reliant on revenues from gas sales to China, which accounted for 75–80% of its total gas exports in 2024. Ashgabat’s push for more active gas diplomacy has been driven by Russia’s growing presence in the Chinese gas market, a trend that has accelerated since February 2022. The agreement with Turkey offers only modest compensation for the loss of Turkmenistan’s previous gas contract with Russia, which was not renewed in 2024. Under that agreement, signed in 2019, Turkmenistan had supplied approximately 5 bcm of gas annually to Russia.

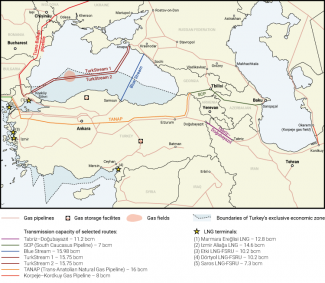

Map. Turkey’s gas pipeline network and terminals

Source: Republic of Türkiye – Ministry of Energy and Natural Resources, enerji.gov.tr; Energy Community, energy-community.org.; BOTAŞ, botas.gov.tr.