Looking for a way out: Latvia’s demographic crisis

Due to its negative natural increase and emigration, Latvia is one of the fastest depopulating countries in the world, losing 18,000–20,000 inhabitants annually – the equivalent of a medium-sized Latvian town. Although the country’s political and intellectual elite recognised the problem following the 2007 economic crisis, Latvia has failed to implement comprehensive measures and devise a political strategy to reverse or at least slow down the negative trends. The gloomy picture of Latvian demography is further blurred by the absence of social consensus on solving these problems, including, to some degree, allowing immigration from outside the EU. Another major issue is the unprecedented magnitude of the Latvian population’s health problems compared to other EU member states.

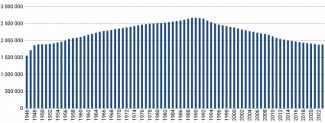

Since 1991, when Latvia regained independence, its population has declined steadily. In the late 1980s and early 1990s, the country had a population of 2.66 million. Over the last three decades, a wave of emigration has occurred, motivated by both political and economic reasons. In the 1990s, the majority of Russian speakers who had settled in Latvia during the Soviet era left the country. This included a portion of workers from large industrial plants and a significant number of military personnel who served in the Latvian SSR.

After Latvia’s accession to the EU in 2004 and in the wake of the economic crisis of 2008–10, the scale of economic migration to other EU member states increased, particularly to the UK and Germany. Alongside a steep decline in fertility rates and high death rates recorded since the 1990s, migration over the past 35 years has resulted in the Latvian population declining by 780,000. Currently, the population numbers 1.872 million , which is almost a third fewer than in the early 1990s.

Chart 1. Latvia’s population from 1946–2023 (recorded at the beginning of each year)

Source: figures compiled by Latvia’s statistical office, stat.gov.lv.

Chart 2. Latvia’s population change from 1946–2023

Source: figures compiled by Latvia’s statistical office, stat.gov.lv.

Latvia: the land of migration

Migration has significantly impacted Latvia’s demography from the second half of the 20th century to the beginning of the 21st century. Immigration and emigration fundamentally changed its population. In the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s, due to the USSR’s colonial policy, large groups of Sovietised individuals were brought to the territory of the Latvian SSR from other parts of the Soviet empire. The largest groups of immigrants came from the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic and the Belarusian SSR.

In the final three decades of the USSR’s existence, the Latvian population increased by 350,000 due to immigration alone. Moscow’s settlement policy was guided by economic and political objectives, expecting the newcomers to join the workforce of large industrial plants and to boost the republic’s political stability by increasing the proportion of people who were loyal to the Soviet authorities. The influx of new residents from other Soviet republics was so intensive that it sometimes exceeded the local rate of natural increase.[1]

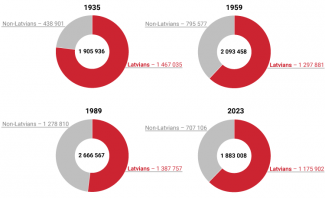

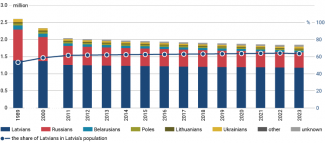

Chart 3. Proportion of Latvians and non-Latvians in Latvia in the 20th and 21st century

Source: figures compiled by Latvia’s statistical office, stat.gov.lv.

A radical reformatting of Latvia’s ethnic and social composition was the long-term consequence of the Soviet settlement policy. According to population censuses taken during Latvia’s independence (1935) and the final one carried out in the Soviet era (1989), the number of ethnic Latvians remained almost unchanged, while that of non-Latvian residents increased threefold. In 1935, minorities accounted for around 25% of the country’s population, while in 1989 they made up as much as 48%.

The Soviet-era politically-controlled immigration trend halted when Latvia regained independence, and then was replaced with a permanent emigration trend. The past three decades have seen four of the most significant waves of emigration from Latvia.

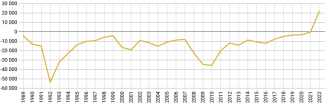

The first, occurring in the 1990s, involved the return of some of the former immigrants to the countries that emerged following the collapse of the USSR. This was due to Latvia’s naturalisation policy, its tough economic situation, and the emigration of families of Soviet officials and military officers. The departures reached their apogee in 1992, when around 60,000 individuals left the country. With each successive year, the net migration rate moved closer to zero, after which it stabilised at -5,000 individuals in the second half of the 1990s.

The second wave of emigration took place before Latvia’s EU accession (from 2000–3), when, despite relatively fast GDP growth, the country faced a surge in the unemployment rate and relatively low wages.[2] This situation was largely due to the financial crisis which occurred in Russia (1998), which also affected the economies of the Baltic states.

After Latvia’s entry to the EU in 2004, the pre-accession wave of emigration transitioned into a post-accession wave, with emigrants choosing different destinations. Before 2004, the number of departures to EU member states and to the former USSR was balanced. However, post-2004, emigration to post-Soviet countries (mainly Russia) halted and effectively vanished over time, while the ‘EU-bound’ trend gained momentum.

Between 2000 and 2007, the number of Latvian residents leaving the country remained high, at around 15,000–20,000 individuals annually, with the net migration rate continuing to be negative (around -10,000 individuals annually). The highest intensity of departures to the West occurred after 2007, during the global financial crisis. At its peak (2008–11), around 130,000 people left Latvia, with the net migration rate reaching around -35,000 individuals annually in the most difficult years of 2009 and 2010.

The 2007–10 global economic crisis and its consequences provided a long-term impetus for emigration. Although the Latvian economy began to recover in the 2010s, Latvian residents continued to leave the country in large numbers, due to the slower distribution of economic growth to some regions. Latvia only managed to return to the pre-crisis rates in 2017, after ten years of increased emigration. At this point, the migration figures stabilised at around 11,000–15,000 departures annually. However, the negative emigration trend gradually decreased due to immigration and re-emigration, which began in 2013, resulting in the net migration rate gradually moving closer to zero between 2018 and 2021. In the record year 2021, it stood at just -286 individuals.

Chart 4. Net migration rate

Source: figures compiled by Latvia’s statistical office, stat.gov.lv.

The outbreak of a full-scale war in Ukraine triggered a temporary change in migration trends. According to Latvia’s statistical office, in 2022, 38,000 individuals arrived in the country, the highest number ever recorded. Most of them were Ukrainians seeking refuge. At that time, for the first time since regaining independence, Latvia’s net migration rate was positive, and stood at +22,000 individuals. A year later, the number of people seeking protection in Latvia was 4,400, and some of the former asylum seekers left Latvia in search of another country to live. According to figures for January 2024, the number of war refugees Latvia hosted was just 25,700.

Negative rate of natural increase

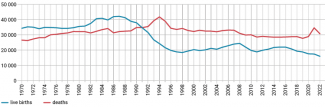

The permanently negative net migration rate, which continued until 2022, is just one of the problems regarding Latvia’s demography. The declining birth rate is of far greater significance, combined with a relatively stable death rate, which since the mid-1990s has stood at around 30,000 to 35,000 deaths annually, significantly exceeding the number of births.

1992 was the first year that saw a negative rate of natural increase, which has continued to decline steadily since then. In the 2010s, it stood at –8,000 – -10,000 and declined further between 2020 and 2023. This decline was due to excess deaths caused by COVID-19 and a significant drop in the number of births. Consequently, due to these two factors, Latvia’s current rate of natural increase is the lowest in its history. In 2022, it was -17,200, and in 2023, it was -15,800.

Chart 5. Number of live births and deaths from 1970–2023

Source: figures compiled by Latvia’s statistical office, stat.gov.lv.

There is little indication that the trend of declining birth rates with unstable death rates will reverse in the near future. Since 2022, Latvia has recorded highly negative statistics in this regard. The lowest birth rate in the last 100 years was recorded in 2023, when only 14,000 children were born. Compared with figures from the previous decade, Latvia has on average 6,000–7,000 fewer live births each year. Compared with the statistics of the early 1990s, the scale of decline is 20,000 fewer live births annually.

This situation is largely attributed to the cultural transition typical of all developed countries. Additionally, a steady decline in living standards in Latvia’s rural regions is not conducive to having children. This has resulted in a significant drop in the number of births outside the capital region, which is wealthier than the rest of the country.[3]

The reasons for the persistently high number of deaths also include public health problems. Statistics indicate that cardiovascular diseases account for as much as half of these deaths. According to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), these diseases are significantly correlated with the lifestyle of the country’s population, which includes an unhealthy diet, smoking, high alcohol consumption, and insufficient physical activity.[4]

OECD statistics indicate that almost 25% of all deaths in Latvia are closely linked to dietary habits (the EU average is 17%). In addition, Latvia has the EU’s highest consumption of pure alcohol per capita (12.2 litres, followed by Lithuania with 12.1 litres and the Czech Republic with 11.6 litres[5]). Latvian men are also among the biggest tobacco consumers. According to figures compiled by the OECD in 2020, as much as 35% of Latvian men smoked daily (the average proportion recorded for the EU as a whole was just 20%).[6]

The pessimistic picture of Latvia’s public health is further darkened by a demanding situation in the healthcare sector which persistently grapples with challenges such as limited availability of medical services, staff shortages, and insufficient funding. Access to healthcare varies depending on geographical factors: while in Riga there are 6.6 physicians per 1,000 residents, in other regions the proportion is between 1.9 and 2.2 (the EU average is around 4.3). Most healthcare facilities are located in bigger cities, resulting in residents of rural regions having difficulties accessing a major portion of medical services.[7]

The demographic crisis is affecting minorities

Negative demographic phenomena, such as migration, low birth rates and public health problems, affect Latvia’s Russian-speaking residents more frequently than ethnic Latvians. Moreover, it is primarily national minorities who bear the consequences of the demographic crisis. Between 1989 and 2023, the number of ethnic Latvians fell by around 211,000, accounting for just about a third of the total population loss. There are significant differences between these individuals and the Russian-speaking population regarding all the indicators mentioned earlier, including the rate of natural increase, migration patterns, and health-related challenges.

Chart 6. Latvia’s population according to ethnic background (at the beginning of each year)

Source: figures compiled by Latvia’s statistical office, stat.gov.lv.

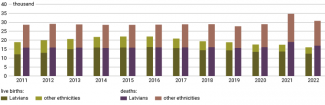

Significant disparities are evident, for example, in birth and death statistics. Over the last decade, the number of children born to Latvians was three to four times higher than the corresponding figure for other nationalities. In terms of the number of deaths, no such significant differences have been recorded. This indicates that the non-Latvian population will shrink at an increasingly rapid rate in the future. This difference is also evident in the rate of natural increase. Over the last decade, for Latvians it was sometimes close to zero (e.g. in 2014–7), with extreme values standing around -3,000 (except in 2021, when the statistics were distorted by excess deaths due to COVID-19). In contrast, the number of deaths in the non-Latvian part of the population is on average three to four times higher than the number of births. For example, in 2020, there were only 4,100 births and 12,800 deaths among non-Latvian ethnic groups.

Chart 7. Live births and deaths according to ethnic background

Source: figures compiled by Latvia’s statistical office, stat.gov.lv.

Migration patterns also differ. In the 1990s and 2000s, Russian speakers were overrepresented among those who left the country. This trend continued until the end of the 2010s and then slowly subsided. In the past decades, the emigration of Latvia’s Russian-speaking residents was strongly motivated by their inferior status in the labour market, resulting, among other things, from their insufficient knowledge of the Latvian language and their feeling of internal alienation[8].

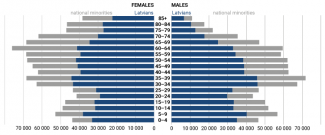

The public health challenges are more complex in nature. Aside from ethnic background, gender plays a significant role. This is particularly evident in the life expectancy statistics. Men have a life expectancy of around 69 years, which is 10 years shorter than that of women. An unhealthy lifestyle is also slightly more common among Russian-speaking men than among ethnic Latvian men.[9] Ethnic Latvian women have the longest life expectancy measured in years of good health, while Russian-speaking men have the shortest life expectancy.

Chart 8. Population pyramid according to ethnic Latvians and national minorities

Source: figures compiled by Latvia’s statistical office, stat.gov.lv.

Outlook: the vicious cycle of demography

Assuming that in the long term the net migration rate stabilises at around zero, Latvia’s population will continue to decline, mainly due to the persistently high number of deaths. According to projections prepared by Eurostat, over the next few decades the country may become less populous than neighbouring Estonia. By 2045, Latvia’s population is projected to be 1.5 million, and by around 2060, it is expected to be smaller than Estonia’s, which is estimated to have a population of 1.27 million at that time. By 2100, Latvia’s population is expected to shrink to just 1.16 million.[10]

The declines forecast by Eurostat will continue to affect the Russian-speaking population to a greater degree, as its rate of natural increase is significantly lower than that of ethnic Latvians. This indicates that, in the long term, the country’s population will shrink rapidly and at the same time become more Lettonised. This will result in an end to the social polarisation regarding the role and situation of the Russian-speaking population that has been present over the last 35 years.

Avoiding depopulation seems impossible. Riga has neither a short-term nor a long-term policy that could halt the trends forecast by Eurostat. Although an influx of non-EU immigrants could delay Latvia’s demographic problems for at least several years, neither the country’s political elite nor its public are ready for such a scenario due to negative attitudes towards immigration[11], even a controlled one. The current legislation is also not conducive to it, on the contrary, it actively prevents it[12] and the state is determined to limit the number of newcomers from non-EU countries as much as possible.[13]

The trauma of Soviet-era controlled immigration is a significant part of the identity of the Latvian portion of society, pushing the debate about accepting foreigners into the taboo sphere. In this context, a possible change in stance is also hampered by the fact that the post-Soviet states form a potential reservoir of foreign workers, and that Russian would frequently be the first language of communication for these immigrants upon their arrival in Latvia. This, in turn, could magnify Latvians’ concerns about the increasing spread of the Russian language in public spaces.

Reforming the public health sector could be a relatively easy method for halting the rapidly occurring negative phenomena affecting the Latvian population. Policies aimed at promoting healthy lifestyle choices among Latvia’s residents, with special emphasis on reducing alcohol and tobacco consumption, could lower the number of deaths. At the same time, the effectiveness of these measures could be increased by solving the institutional problems of the healthcare system, which should include efforts to increase the availability of medical services outside Riga.

Another method for mitigating the demographic ills, at least to some degree, could involve the re-emigration of the 370,000 Latvians who live abroad. To achieve this, the state would need to devise a comprehensive re-emigration policy, which is currently almost non-existent. This policy should include not only incentives for these individuals to return to Latvia, but also solutions to relocation-related problems faced by potential re-emigrants. The number of returns could also be significantly increased, if Latvia boosted its economic potential, especially in regions outside the capital city.

Achieving a rapid increase in the fertility rate of the Latvian population seems to be the most difficult challenge and is almost impossible to tackle. The steadily declining birth rate is linked to social and cultural changes, as well as Latvia’s worsening economic situation.[14] Latvia’s depopulation is accelerated by inequalities, as the quality of life in the regions is much lower than in the Riga metropolitan area. Thus, Latvia is trapped in a demographic vicious cycle with fewer children being born in rural regions due to their poorer economic standing and less developed infrastructure, while the low fertility rate contributes to further degradation.

[1] J. Riekstiņš, Colonization and Russification of Latvia 1940–1989 [in:] The Hidden and forbidden history of Latvia under Soviet and Nazi occupations 1940–1991, Institute of the History of Latvia, Rīga 2005, p. 234–238.

[2] M. Hazans, Emigration from Latvia: Recent trends and economic impact [in:] Coping with Emigration in Baltic and East European Countries, OECD, 2013, p. 76, after: academia.edu.

[3] B. Chmielewski, ‘Far behind Riga. Latvia’s problems with uneven development’, OSW Commentary, no. 498, 15 March 2023, p. 4–5, osw.waw.pl.

[4] State of Health in the EU: Latvia – Country Health Profile 2021, OECD/European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, Paris/Brussels 2021, p. 5, health.ec.europa.eu.

[5] ‘Alcohol consumption’, OECD, data.oecd.org.

[6] E. Zicāns, ‘Why do Latvian men die young?’, Latvijas Sabiedriskie Mediji, 22 November 2023, eng.lsm.lv.

[7] State of Health in the EU: Latvia – Country Health Profile 2021, op. cit., p.7.

[8] M. Krumina, K. Fredheim, Z. Varpina, ‘Who is More Eager to Leave? Differences in Emigration Intentions Among Latvian and Russian Speaking School Graduates in Latvia’, Society. Integration. Education 2021, no. 6, after: journals.ru.lv.

[9] D. Grīnberga et al., Latvijas iedzīvotāju veselību ietekmējošo paradumu pētījums, 2022, Slimību profilakses un kontroles centrs, Rīga 2023, p. 70–160, spkc.gov.lv.

[10] ‘Latvia's population could fall to 1 million by century's end’, Latvijas Sabiedriskie Mediji, 30 March 2023, eng.lsm.lv.

[11] ‘Survey: Latvian public unenthusiastic about Ukrainians staying on after war's end’, Latvijas Sabiedriskie Mediji, 24 January 2024, eng.lsm.lv.

[12] Immigrants from non-EU countries have more difficult access to the job market due to language skill requirements. See S. Ambote, ‘Under half of Ukrainians in Latvia are employed’, Latvijas Sabiedriskie Mediji, 24 January 2024, eng.lsm.lv.

[13] ‘Par to bijušās PSRS pilsoņu statusu, kuriem nav Latvijas vai citas valsts pilsonības’, Likumi.lv.

[14] An outdated system of family support, which fails to meet the needs of Latvian society, is one of the reasons why Latvian citizens are not willing to expand their families by having (more) children. An allowance for the first child is 25 euros; it is increased to 100 euros per child, when a family has at least four children. ‘Ģimenes valsts pabalsts’, Labklājības ministrija, 25 March 2023, lm.gov.lv.