Ukraine on the financial front – the problem of Ukraine’s foreign public debt

One of the key challenges that Ukraine is facing is the scale of its foreign debt (both public and private). As of 1st April it stood at US$ 126 billion, which is 109.8% of the country’s GDP. Approximately 45% of these financial obligations are short-term, meaning that they must be paid off within a year. Although the value of the debt has fallen by nearly US$ 10 billion since the end of 2014 (due to the private sector paying a part of the liabilities), the debt to GDP ratio has increased due to the recession and the depreciation of the hryvnia. The value of Ukraine’s foreign public debt is also on the rise (including state guarantees); since the beginning of 2015 it has risen from US$ 37.6 billion to US$ 43.6 billion. Ukraine does not currently have the resources to pay off its debt. In this situation a debt restructuring is necessary and this is one of the top priorities for the Ukrainian government as well as for the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and its assistance programme. Without this it will be much more difficult for Ukraine to overcome the economic crisis.

The Ukrainian government is currently negotiating with a group of private creditors (mainly American investment funds) which holds approximately 40% of the entire value of the bonds. A possible cancellation of part of the debt remains an essential element of the dispute. Kyiv is opting for this solution, whereas the private creditors are opposed to it—they agree only to relax the conditions of debt payment (reduced interest rates and an extension of the debt’s maturity) and a slight haircut. The negotiations began in April and gathered momentum in July. At present it is hard to predict the outcome. However, neither party wishes to see Ukraine defaulting, which leaves open the chance for an agreement to be reached.

The debt that Ukraine owes to Russia will also be an important challenge for Ukraine since in this case chances of debt restructuring are slimmer. This applies above all to the payment of US$ 3 billion borrowed under Viktor Yanukovych’s presidency and which reaches maturity in December 2015. Russia is categorically refusing to discuss debt restructuring, let alone writing any of it off. Kyiv is currently focusing on the negotiations with the private creditors, hoping that success in these talks will strengthen its hand in its relations with Russia.

Ukraine’s foreign debt

In 2014 the value of Ukraine’s foreign debt decreased, however the debt to GDP ratio increased. This was mainly due to a drop in the country’s GDP and the depreciation of the hryvnia. According to data from the National Bank of Ukraine (NBU), at the beginning of January 2015 gross foreign debt totalled US$ 126.3 billion, against US$ 142 billion in 2014. However, at the same time the gross foreign debt to GDP ratio increased from 74.6% to 95.1%. Even though the debt in total fell by over ten billion US dollars, due to a considerable decline in GDP the debt to GDP ratio is higher than it was in 2014. According to the NBU’s recent data, at the end of the first quarter of 2015 gross foreign debt in total fell to US$ 126 billion, which nevertheless represented 109.8% of the country’s GDP. The IMF’s estimates indicate that the debt may reach 158% of GDP this year due to the expected decline in Ukraine’s GDP in 2015.

Ukraine’s gross foreign debt in 2011-2015, the value in US$ billion and the percentage of GDP at the end of the period

Source: the National Bank of Ukraine

The nominal value of the foreign debt fell due to the reduction in private sector debt. However, in 2014 state sector debt grew, above all due to the loans Ukraine had been granted under international assistance programmes, including those offered by the IMF, the EU, the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) or loans granted by particular countries such as the US, Japan and Canada. According to the IMF, in 2014 private sector debt decreased from US$ 110.4 billion to US$ 97.6 billion (from 61.4% of GDP to 76.2% of GDP), whereas public sector debt increased from US$ 30.2 billion to US$ 33.6 billion (from 16.8% to 26.2% of GDP). At the end of 2014 the value of public debt and state guarantees in total stood at US$ 70.8 billion, which accounted for 72.7% of GDP (compared with 40.6% of GDP at the beginning of 2014). Foreign debt made up 55.6% of public debt and reached US$ 39.4 billion in total, including US$ 8 billion in state guarantees. The value of the Eurobonds and government guarantees amounted to US$ 17.3 billion. The remaining public debt comprised the government’s guarantees for loans and bonds issued by state-owned companies, the debts incurred by the local authorities and the NBU’s liabilities to the IMF. The latest statistics from the Ministry of Finance of Ukraine which were published on 31st May 2015 reveal public debt at a level of US$ 33.9 billion and state guarantees amounting to US$ 9.7 billion (including nearly US$ 1 billion in state guarantees for loans granted by the Russian banks VTB, Gazprombank and Sberbank). In the structure of public debt the share of the financial obligations to international financial institutions (including the IMF, EIB and EBRD) was US$ 12.8 billion, bilateral debt was US$ 1.2 billion (including US$ 0.6 billion owed to Russia) and the value of issued bonds amounted to US$ 18.2 billion.

The structure of Ukraine’s public debt as of 31st May 2015 in US$ thousand

|

Category |

|

US$ thousand |

|

Total public debt and state guarantees |

|

67,660,179 |

|

Total public debt |

|

56,735,956 |

|

Internal debt |

|

22,868,079 |

|

Foreign debt |

|

33,867,877 |

|

1. Debt owed to international financial institutions: |

|

12,781,551 |

|

|

EU |

1,754,255 |

|

|

European Bank for Reconstruction and Development |

540,156 |

|

|

European Investment Bank |

431,094 |

|

|

World Bank |

4,236,499 |

|

|

International Monetary Funds |

5,819,095 |

|

|

Clean Technology Fund |

450 |

|

2. Debt to other countries |

|

1,174,974 |

|

|

Canada |

320,612 |

|

|

Germany |

7,627 |

|

|

Russia |

605,856 |

|

|

US |

10,447 |

|

|

Japan |

230,432 |

|

3. Debt owed to commercial banks |

Chase Manhattan Bank Luxembourg S.A. |

56 |

|

4. Issuance of securities on foreign markets (Eurobonds) |

|

18,203,760 |

|

5. Other categories of debt |

International Monetary Fund |

1,707,536 |

|

Total state guarantees |

|

10,924,223 |

|

State guarantees for internal debt |

|

1,273,498 |

|

State guarantees for foreign debt |

|

9,650,724 |

|

1. Debt to international financial institutions |

|

4,460,430 |

|

|

European Atomic Energy Community |

23,571 |

|

|

European Bank for Reconstruction and Development |

84,821 |

|

|

World Bank |

368,208 |

|

|

International Monetary Fund |

3,983,828 |

|

2. Debts owed to other countries |

Canada |

219,325 |

|

3. Debts owed to commercial banks |

|

3,049,723 |

|

|

Citibank, N.A. London |

60,993 |

|

|

Credit Suisse International |

126,000 |

|

|

Deutsche Bank AG London |

7,143 |

|

|

UniCredit Bank Austria AG |

50,911 |

|

|

VTB Capital PLC |

73,467 |

|

|

Gazprombank |

500,000 |

|

|

China Development Bank |

78,540 |

|

|

Export-Import Bank of China |

1,552,124

|

|

|

Export-Import Bank of Korea |

179,403 |

|

|

Sberbank |

421,143 |

|

4. State guarantees for securities issued by: |

Fininpro (state-run infrastructure investment agency) |

1,808,000 |

|

5. Other categories of debts |

International Monetary Fund |

113,247 |

Source: Ministry of Finance of Ukraine

The high level of foreign debt and its structure poses one of the greatest threats to the stability of Ukraine’s economy and its chances of overcoming the crisis. On the one hand, there are high risks linked with Kyiv’s limited capacity to service the debt due to its high costs following the depreciation of the hryvnia, a fall in exports, and the low level of foreign-exchange reserves. As of 1st January 2015 the total value of short-term gross foreign liabilities (including the private and public sectors) amounted to US$ 55.1 billion, whereas the total value of the foreign debt reached 184.4% of the value of exports. Foreign-exchange reserves were estimated at US$ 7.5 billion (due to foreign support, the foreign-exchange reserves reached the level of US$ 10.26 billion on 1st July 2015).

Furthermore, Ukraine has very limited access to foreign financial markets and sources of financing. It faces great difficulties in accessing foreign loans and they are very expensive. This is proven, among other factors, by the high value of credit default swaps (CDS) for Ukraine, an indicator which makes it possible to assess the current perception of the credit risk by financial markets. In the case of Ukraine the CDS is estimated at 19.2% (as of 13th April 2015) and comparable to the indicators for Venezuela and Argentina, whereas it is 1.2% for Poland, 0.2% for Germany and 5.1% for Russia.

The restructuring of Ukraine’s debt - the priority in the reform programme

The restructuring of Ukraine’s internal debt is one of the top priorities for the stabilisation of the economic and financial situation of the country both in the policy pursued by the Ukrainian government and in the policies of foreign assistance programmes, including the key programme of the IMF. The programme is set to relieve the burden of the economy and public finance which has been brought about by debt servicing, and to facilitate the use of funds to reconstruct foreign-exchange reserves and to implement economic reforms. The main objectives of the IMF programme, which is worth US$ 17.5 billion and will be implemented in 2015–2018, are the following: 1) to generate US$ 15.3 billion through debt restructuring (although the IMF does not specify how the restructuring will be conducted and leaves it to be negotiated with Ukraine’s creditors); 2) to reduce public debt to 71% of GDP by 2020; 3) to keep the costs of debt servicing below 10% of GDP a year on average from 2019–2025 (not more than 12% of GDP in any one year). The IMF expects that these measures will enable Ukraine to return to the international financial markets in 2017, which will allow Ukraine to involve private capital in the economic reconstruction of the country and will enable it to gain access to funding from sources other than the IMF, other international financial institutions or countries. The IMF assumes that in 2017-2020 Ukraine will succeed in obtaining approximately US$ 7 billion of capital from the private sector. The reduction of the debt is a significant element in the implementation of the programme of co-financing Ukraine. The programme is aimed at assuring that the country’s financial needs are met and it represents 38% of the value of aid programmes which the IMF estimates at US$ 40 billion (including financial assistance from the IMF and also other sources)..

The debt restructuring under the IMF programme for Ukraine, in US$ billion

|

|

|

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

2018 |

In total |

|

Ukraine’s financial needs |

21.4 |

6.8 |

6.9 |

4.8 |

40.0 |

|

|

|

Increase in currency reserves |

10.8 |

3.9 |

6.3 |

6.7 |

27.7 |

|

|

Deficit in current account balance |

10.6 |

2.9 |

0.7 |

-1.9 |

12.3 |

|

Financing |

21.4 |

6.8 |

6.9 |

4.8 |

40.0 |

|

|

|

Total financial support |

16.3 |

3.5 |

2.5 |

25 |

24.7 |

|

|

Debt restructuring |

5.2 |

3.4 |

4.4 |

2.3 |

15.3 |

|

The share of the debt restructuring in financing Ukraine’s needs, in percentage |

24% |

50% |

64% |

48% |

38% |

Source: International Monetary Fund, Ukraine: Request for Extended Arrangement under the Extended Fund Facility and Cancellation of Stand-by Arrangement, 2015

At present Ukraine does not have the financial resources to pay off all of its foreign liabilities on time. The factors which have contributed to this are as follows: the economic crisis (including the dramatically low level of foreign-exchange reserves, the recession, a decline in exports, the depreciation of the national currency, the deficit in the current account balance, the lack of stability of the banking and financial systems), military operations in the east of the country and the conflict with Russia as well as instability within Ukrainian politics (including the lack of a stable political structure in parliament or in local authorities, rivalry between political parties and the resistance of society and local oligarchic elites to the implementation of radical reforms).

In this situation the restructuring of foreign debt is crucial. The Ukrainian government wishes to restructure bonds and the state-guaranteed bonds of state-run companies by reducing their value, extending their maturity and cutting the coupon. They are worth a total of at least US$ 21.74 billion, although their value should be estimated at US$ 23 billion. In the first place this concerns the debt owed to a group of private bondholders (investment funds, mainly American) and US$ 3 billion in the loan granted by Russia. At present the loans granted by international financial institutions and countries are not included in the negotiations.

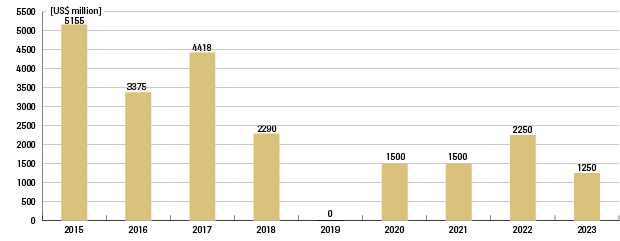

The value and maturity of bonds and state-guaranteed bonds, in US$ million

Source: MSN News, Ukraine-Crisis/Creditors, 20.05.2015, accessed: http://www.msn.com/en-my/news/other/ukraine-crisis-creditors-factbox/ar-BBjZJKY

The standout feature of Ukraine’s debt is its extraordinary concentration, i.e. a handful of creditors hold the bulk of it On the one hand, this state of affairs can be beneficial for Ukraine since reaching agreement with its key bondholders will allow it to restructure a large part of the debt. On the other hand, the key bondholders have a much stronger negotiating position. All Ukraine’s foreign bonds are governed by British law.. This makes it impossible for Kyiv to use its domestic law in order to influence the management of the debt (e.g. to break the opposition of the bondholders).

The ‘Western front’

The Ukrainian government has started off negotiations on restructuring its debt with private Western creditors. These are Western investment funds, mainly American ones. Franklin Templeton is the largest holder of Ukrainian bonds, with an estimated value of US$ 6.5–7 billion (depending on the source). In March 2015 the fund launched an initiative to establish an ad hoc committee of holders of Ukrainian bonds. It was composed of American funds TCW and T. Rowe Price and a Brazilian fund BTG Pactual Europe. The businesses grouped together in the ‘committee of creditors’ in total hold Ukrainian bonds worth approximately US$ 8.9 billion, which represents approximately 40% of the bonds issued. Furthermore, according to the press, Ukrainian bonds are also held by American funds such as PIMCO (owned by Germany’s Allianz), Blackrock, Fidelity and Stone Harbor as well as Germany’s Deutsche Bank.

Negotiations between the Ministry of Finance of Ukraine and the committee of bondholders – with the participation of IMF representatives – are of key importance for private creditors. As part of debt restructuring the Ukrainian government is pushing for the write off of 40% of the debt’s value, a ten-year extension of its maturity and a reduction in interest rates. The creditors are however opposed to debt relief and this remains the major bone of contention. Nevertheless, they are rather favourable to an extension of its maturity and the cutting of the coupon. In the negotiation game currently underway, Ukraine is trying to exercise pressure by threatening to default on particular financial obligations to private creditors (this, however, does not automatically mean the entire country’s default). On 19th May 2015 the Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine adopted a law which enables the government to withhold payments to holders of foreign bonds. The Ukrainian government has declared that it is prepared for a possible default on certain financial obligations and that this will not affect the banking system or the national currency. The fact that the IMF announced in June 2015 that it would continue its assistance programme even if agreement with private bondholders is not reached is significantly helpful for Ukraine. On 2nd July the IMF agreed to the payment of another tranche of the financial aid to Ukraine, worth US$ 1.7 billion. It will be transferred to Ukraine once the country meets the conditions of the current IMF programme.

Kyiv in negotiations with its Western creditors has justified its position saying that it does not have financial resources and does not want to use its foreign-exchange reserves in order to pay off its debt. The Ukrainian government has also emphasised that the creditors lent to the former president, Yanukovych, who was ousted in February 2014, and this helped his regime function. In June 2015 finance minister Natalie Jaresko presented a new proposal which make it possible for part of the costs incurred by the creditors to be compensated to those who agreed to write off Ukraine’s debt, but only if the country’s economic recovery is more rapid than projected.

The private creditors have replied that defaulting on the debt will prevent Ukraine from having access to the international financial markets. This will also infringe one of the conditions of the IMF programme which assumes that Ukraine will return to the international financial markets in 2017. Furthermore, it will tarnish the country’s reputation in the eyes of prospective investors. In consequence, Ukraine will find it very difficult to apply for external funding. Foreign private creditors do not want to be the only ones to bear the costs of Ukraine’s debt restructuring since debt relief is supposed to be limited to private bondholders, and not to extend to all creditors (it will not extend to countries or internal creditors). Private creditors claim that Ukraine’s problem is solvency, not the volume of its debt. The proposal they have put forward allows for the debt to be substituted by securities which will be repaid should Ukraine’s GDP increase to a specified level. This, in fact, makes it possible to extend the debt’s maturity and cut the coupon. According to the private creditors this will bring approximately US$ 16 billion to Ukraine in savings and will allow the country to meet the IMF programme’s terms and conditions without debt cancellation. So far the ongoing negotiations have not led to a definite agreement. In April 2015 it was possible to delay the payment of US$ 750 to Ukreximbank, and in August there was a delay in the purchase of bonds worth US$ 1.3 billion issued by the state-run Oschadbank. The negotiations gathered speed in July when during talks with the participation of IMF representatives both parties made certain tactical concessions. These included creditors allowing the possibility of up to 5% of the debt being written off, and the Ukrainian government presented a new proposal. It did not, though, make its details public.

The ‘Eastern front’

For Ukraine the debt it owes to Russia is equally important to its debt to private bondholders. This applies above all to a loan of US$ 3 billion which reaches maturity on 24th December 2015. From Russia’s point of view this loan granted in December 2013 was a political instrument intended to provide support for Viktor Yanukovych after he rejected the EU association agreement. The terms and conditions of the loan seemed to be quite advantageous for Ukraine – a large sum, rapidly transferred, with a 5% interest rate, which was half the rate offered on the financial markets at that time.

However, the loan has proven to be an effective tool which has given Russia considerable leverage in Ukraine. Despite the fact that it is an official, government-to-government loan and both parties – the creditor and the debtor – are state institutions, it is formally a private loan. Russians have deliberately designed it in this manner in order to be able to treat it as they see fit– either as official or a private loan – and to reap the benefits resulting from both forms.

This means that if Ukraine fails to repay this debt, the implications may be the following:

- if the loan is treated as official debt –the IMF aid programme will be halted;

- if it is regarded as private debt –the possibility to take out loans on the private financial markets will be blocked.

Although the statements which representatives of Moscow have made thus far treat this loan as bilateral debt, Russia has not reported it to the Paris Club (an informal group of national creditors which deals with states’ debts). Formally, in the transaction the Russian National Wealth Fund bought Ukrainian bonds which are governed by British law and listed on the Irish stock exchange. This limits Ukraine’s possibilities to use its domestic law in order to defend its interests. Another provision which gives Russia considerable leverage is the possibility to call in the loan if Ukraine’s public debt exceeds 60% of GDP. This occurred in spring 2015. So far, though, Moscow has not used this option.

The manner in which the loan agreement was designed substantially limits Ukraine’s possibility to restructure it and is very beneficial to Russia. The government in Kyiv officially treats this loan as private debt and thus subject to restructuring. However, this is being controversial from a legal point of view. This is important since according to IMF rules it is impossible to grant financial aid to countries which have defaulted on financial obligations to other countries. The IMF has not yet taken a clear stance on this issue. However, when complicated Ukrainian-Russian relations are taken into account, with the conflict occurring on many different levels (political, military, economic, energy), the Ukrainian government are focusing above all on peace talks (the Minsk and Normandy formats) and gas negotiations. It has not yet taken any steps in order to deal with its debt apart from calling for talks about it. Russia, however, has rejected this proposal. Up to now Kyiv has been fulfilling the commitments of the agreement with Russia. On 20th June Ukraine paid US$ 75 million in interest rates on time.

Unlike Western creditors, who are motivated solely by business interests and possible profits, Russia sees financial instruments above all as a tool to achieve its political goals. In the conflict with Ukraine the Kremlin has not yet decided to use the financial instrument and completely destabilise the Ukrainian financial system, for example by demanding that the loan be repaid. The reason for this is that the Kremlin is interested in avoiding Ukraine’s total economic collapse since this would have grave economic implications for Russia due economic ties that bind the two countries and the interests of Russian businesses (for example, Russia is the fifth largest investor in Ukraine). Despite this Ukrainian debt remains an effective tool which can be employed at any time in order to apply pressure on Kyiv. One of the options which would allow Kyiv to neutralise this instrument of coercion would be to pay off the debt on time. Ukraine, however, does not have the financial resources to repay it (the debt accounts for 30% of its foreign-exchange reserves which are far below the safe level anyway). Another problem is that this move would deprive Ukraine of arguments in its negotiations with private bondholders, in which it is demanding the cancellation of 40% of the debt.

The spectre of a Ukrainian default?

In a situation in which Ukraine does not have the financial resources to pay off the entirety of its of debt, the game is focused on who will bear the costs of helping Ukraine out of its financial crisis and to what extent: Kyiv or the countries and international institutions which provide aid to Ukraine or private and state creditors, including Russia. It seems nobody wants to see Ukraine default – not the creditors since they would lose any chance of getting their money back, not Ukraine because this would prevent it from having access to international financial markets, not the Western countries (mainly Germany) and the IMF because this would lead to increased economic assistance provided to Ukraine (the IMF wants Ukraine to seek funding on private capital markets, not to borrow from the IMF). As for Russia, on the one hand it is interested in further weakening Ukraine. On the other hand, were Ukraine to default, the financial collapse would affect the business interests of Russian companies.

At present the course and results of the negotiations with private creditors will be of crucial importance. On 24th July Ukraine paid US$ 120 million in coupon on time. On 23rd September sovereign bonds worth US$ 500 million will reach maturity. Should no agreement be found with private creditors, Ukraine has declared it is ready to default on these obligations.

This paper was completed on 4th August 2015.