The shades of German anti-Semitism

The streets of Germany’s biggest cities are increasingly witnessing frequent anti-Semitic incidents. Despite the fact that Germany regards the fight against anti-Semitism as part and parcel of its domestic policy, in recent years Jews living in Germany have reported that they feel under threat, to such an extent that 44% of them are considering migration. Debates on the presence of ‘imported anti-Semitism’ among refugees from Arab states who have come to Germany in recent years have been held for several months. Anti-Semitism among asylum seekers is a new element in the dispute that has been evident in Germany over the attitude of specific parties to anti-Semitism and methods for combating it. Both Alternative for Germany (AfD) and the Left Party are accused by other parties of insufficient efforts to eliminate instances of anti-Semitism in their ranks. The AfD, for its part, accuses Chancellor Angela Merkel of having contributed to an increase in xenophobic tendencies by pursuing a liberal migration policy.

Significant differences between the statistics concerning incidents (which suggest that the perpetrators are most often right-wing extremists) and the accounts given by the victims (who point to individuals of migrant origin as the perpetrators) have triggered doubts regarding the methodology used to compile these statistics. Attempts by the Federal Ministry of the Interior to monitor anti-Semitic incidents, which is a practice recommended by non-governmental organisations, may help to improve the credibility of the statistics by showing the motivation behind such attacks in a broader context. Activities carried out by the federation and by individual German states focus on curbing anti-Semitism on the internet and in schools, which is where incidents involving discrimination and attacks are becoming increasingly common.

The Jewish diaspora in Germany

After World War II, the fight against anti-Semitism became an important element of state doctrine and German-Israeli relations gained a special status. 1965 marked the onset of official diplomatic relations and in June 1973 Willy Brandt paid a visit to Israel as the first German chancellor. Two years later, Israeli prime minister Yitzhak Rabin paid a return visit to Germany. The speech chancellor Angela Merkel delivered in the Knesset on the occasion of the 60th anniversary of the establishment of the state of Israel was one of the break-through moments. In her speech the chancellor presented the main direction of Germany’s foreign policy towards Israel: “Here of all places I want to explicitly stress that every German Government and every German Chancellor before me has shouldered Germany’s special historical responsibility for Israel’s security. This historical responsibility is part of my country’s raison d'être. For me as German Chancellor, therefore, Israel’s security will never be open to negotiation”.

Israel is Germany’s most important partner in the Middle East in the fields of the economy, politics and security policy. This is manifested, for instance, in Germany granting Israel assistance in its purchases of armaments, supporting it in the EU forums, and in assistance offered by the Bundeswehr – such as in 2006 when,

After World War II, the fight against anti-Semitism became an important element of state doctrine and German-Israeli relations attained a special status.

at Israel’s explicit request, German troops were sent to the Middle East region to supervise the embargo on arms supply to Lebanon (the UNIFIL mission).Chancellor Merkel has visited Israel seven times, each time emphasising the special nature of German-Israeli relations. Germany holds regular intergovernmental consultations with Israel (which is one the few countries covered by this cooperation scheme) and decisions worked out during these events delineate the directions of bilateral cooperation. At the same time, Germany’s relations with Israel are not free from tension. For some time now, the government in Berlin has been opposed to Israeli settlement activity on land privately owned by Palestinians in the West Bank, because it sees it as a barrier to a durable resolution of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, based on the principle of co-existence of the two states.

At present, the population of Jews living in Germany is around 250,000, of which 100,000 are members of Jewish communities. 108 communities are grouped in 23 regional associations belonging to the Central Council of Jews in Germany. A decidedly smaller portion of the diaspora, which is organised in associations and communities, i.e. around 5%, belongs to around 40 Jewish cultural associations and the Union of Progressive Jews in Germany (Die Union progressiver Juden in Deutschland K.d.ö.R.), which is associated with Reform Judaism. The biggest Jewish communities are found in Berlin (around 11,000 members), Munich (8,000) and Düsseldorf (7,000). Large-scale immigration of Jews from former Soviet Union states to Germany has been of key importance for the expansion of the Jewish diaspora in Germany following the country’s reunification. In 1990–2017, 232,000 Jewish immigrants came to Germany (of the 250,000 Jewish people presently living there), many of whom joined Jewish communities. Several new synagogues were built and a number of new regional Jewish organisations were established. In 2003, an agreement was signed between the German state (represented by the Ministry of the Interior) and the Central Council of Jews, in which Germany committed itself to support the Jewish population in Germany. A subsidy worth 13 million euros annually intended to back the Council’s operations is a concrete demonstration of this support. In addition, federal state police protect designated buildings owned by Jewish communities, including synagogues, kindergartens and schools, cultural centres and selected restaurants.

The growing sense of threat

Recent years have seen a significant increase in the threat of anti-Semitic attacks as perceived by Jews living in Germany, with the recorded ‘anxiety index’ being one the highest in the EU. This is evident from the study by the Institute for Interdisciplinary Research on Conflict and Violence at the University of Bielefeld (IKG), in which 78% of the respondents reported that over the last five years there has been an increase in the degree of anti-Semitic behaviour in Germany. In a survey commissioned by the European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights (FRA), 41% of German Jews surveyed admitted that in 2018 they had fallen victim to some form of anti-Semitic attack (with the EU average being 28%). This indicates a considerable increase in comparison to the former FRA research conducted in 2012, in which 29% of the surveyed individuals admitted to having been the target of attacks. Moreover, over the last five years 52% of the respondents fell victim to an attack (the proportion for 2012 was 36%).

In 1990–2017, 232,000 Jewish immigrants came to Germany (of the 250,000 Jewish people currently), many of whom joined Jewish communities.

Fears associated with anti-Semitic attacks are causing an increasing number of Jews to contemplate leaving Germany. In 2018, 44% of the surveyed individuals considered emigrating (45% did not); in 2012, 25% of the respondents thought about emigrating (63% did not consider leaving Germany); however, no data is available as regards their actual departures. The fears are reflected in the everyday life of Jews in Germany – 75% say they no longer wear religious symbols in public places and 46% avoid visiting districts and places considered potentially dangerous. This line of thinking is reinforced by recommendations issued by representatives of Jewish communities, who call on Jews to avoid wearing a kippah in public places (Josef Schuster, President of the Central Council of Jews in Germany) and visiting specific districts in cities due to their higher than average rate of anti-Semitic crimes (such as Berlin or Frankfurt).

An increase in the number of attacks

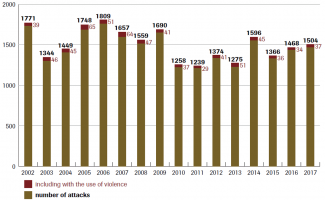

In 2017, anti-Semitic crimes accounted for 4% of all politically-motivated crimes. In 2018, the Federal Ministry of the Interior recorded a 20% increase in the number of anti-Semitic attacks compared with 2017. Out of 1,799 crimes which the Interior Ministry categorised as anti-Semitic in nature, more than 60 were incidents involving the use of violence (representing a 67% rise in such attacks). Since 2001, when the new system of compiling statistics was introduced, the average number of crimes motivated by anti-Semitism has stood at 1,200–1,800 annually, including 28–64 crimes involving the use of violence annually. Until recently, there has been a relationship between the number of crimes and the intensity of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict (an increase to 1,600–1,800 in 2002, 2006, 2009 and 2014). However, the present increase is not directly related to Israeli-Palestinian tension, but is more a continuation of the trend recorded since 2012 (see Appendix: chart 1). The increase in the number of attacks has also been sparked by verbal aggression in social media and in messages sent to institutions (e.g. e-mails), as well as by an increased number of rallies during which anti-Semitic sentiments were expressed. Schools are another forum for increasingly frequent attacks. Teachers point to the absence of suitable instruments for reporting instances of anti-Semitic behaviour, which is particularly frequent in children who come from a different culture, and to the absence of recommended procedures to be followed in such cases.

Fears associated with anti-Semitic attacks are causing an increasing number of Jews to consider leaving Germany. In 2018, 44% of the surveyed individuals considered emigrating.

Most often, anti-Semitic attacks take the form of incitement to violence, dissemination of propaganda materials and symbols of banned organisations, damage to property (including cemeteries, synagogues and restaurants), physical assaults and arson. Nearly half of the crimes are committed on the Internet. The events that caught the most media attention this year included a physical assault on a group of young people wearing kippahs in April 2018 in Berlin. The event was filmed by the assault’s victims and the video was posted online. The most advanced in-depth research focuses on those attacks occurring in Berlin, which has the highest number of incidents among all German federal states and where the Jewish community is the country’s largest. Most frequently, the attacks take place in the street, on public transport, in schools and universities, at the victim’s workplace and in the vicinity of Holocaust commemoration sites. Institutions and non-governmental organisations are more frequently targeted than private individuals. In 2018, 46 attacks involving the use of violence were recorded in Berlin (the figure for 2017 was 18); the total number of victims was 86, including 13 children and young adults. Men were more frequently targeted than women. In the case of 24 individuals their Jewish origin was emphasised and in the case of 43 others the motivation for the attack was that they were considered political opponents with excessively pro-Israeli views.

The increase in anti-Semitic crimes on the Internet is particularly evident. According to German Jews, online anti-Semitism is the most serious problem associated with anti-Semitism in Germany (87% of the respondents support this view). Social media sites provide considerable impetus to the organisational potential of anti-Semitic groups and individuals by enabling them to disseminate content that was less readily available before. In this way these individuals build their network of contacts, making it easier for them to find information on things such as anti-Semitic rallies. The Internet has also made it possible to engage in hate speech on an unprecedented scale. The increase in the number of anti-Semitic comments is of particular importance, considering the fact that more than half of the crimes motivated by anti-Semitism involve incitement to hatred and dissemination of propaganda materials and symbols of banned organisations. In 2007–2017, there was a surge in the number of anti-Semitic comments on websites run by opinion-forming media outlets (including newspapers “Die Welt”, “Die Zeit” and “FAZ”) from 7% to 30%.

Imported anti-Semitism?

The assessment of the relationship between migration to Germany and the increase in the number of anti-Semitic attacks is hindered by the absence of comprehensive research from all German federal states that takes into account the context of admitting refugees who came to Germany in the 2015 migration wave.

Schools are another forum for increasingly frequent attacks. Teachers point to the absence of suitable means of reporting instances of anti-Semitic behaviour that is particularly frequent among children who come from a different culture.

One of the few studies focused on anti-Semitic attitudes of individuals who came to Germany after 2015 was compiled on the basis of research conducted in Bavaria on a group of Syrians, Iraqis and Afghans. The authors have identified more widespread anti-Semitic tendencies in this group of respondents compared with the rest of society, although no direct correlation of these tendencies to attacks motivated by anti-Semitism was found. Experts from the federal Ministry of the Interior have arrived at similar conclusions – they found out that among refugees, anti-Semitic attitudes were reported by 56% of the respondents (whereas the average proportion for Germans is 16–20%). The interior ministry officials attribute the highest proportion (94% in 2017) of anti-Semitic crimes to right extremists. A mere 2% of the attacks were perpetrated by Muslims. This is also confirmed by research conducted by the Berlin-based Technical University (Technische Universität, TU), in which attention was paid to the absence of any link between anti-Semitic attacks and the alleged involvement of asylum seekers in them. In their 2017 report, the experts appointed by the interior ministry presented significantly different figures. Their research findings compiled on the basis of surveys conducted among Jews indicate that 80% of attacks involving the use of violence are perpetrated by Muslims. Moreover, German Jews most frequently point to Muslims as perpetrators of anti-Semitic attacks (41%) among all Jews surveyed in EU states. Research conducted by the IKG with the participation of Jews living in Germany is also important. It showed that most frequently the respondents pointed to Muslims as perpetrators of harassment and insulting behaviour (62%).

The divergence between the small number of anti-Semitic crimes attributed to Muslims in the interior ministry’s statistics and the opinions reported by Jews who have been targets of such attacks raises certain doubts as regards the methods for compiling these statistics and/or the method for surveying the respondents.

The fragmentary nature of the statistics

The differences in the methods for compiling statistics adopted by the police have resulted in the number of reported attacks being understated. This was the conclusion drawn by the expert group appointed by the interior ministry.

Another problem lies in internal categorisation of anti-Semitic crimes, according to which whenever the crime is thought to have been committed by unknown perpetrators, it is categorised as a manifestation of right extremism.

It has also been confirmed by the Berlin-based Centre for Research and Information on anti-Semitism (RIAS). The Centre is considered by the German government’s plenipotentiary for the fight against anti-Semitism as a model example of how a non-governmental organisation should compile its statistics. The Centre’s statistics indicate that in 2016 470 crimes inspired by anti-Semitism occurred in Berlin, whereas the federal state’s counterintelligence unit (LfV) registered 175 such crimes. Some of the differences in the statistics result from the fact that the RIAS includes both crimes and less serious incidents in its statistics.

The main reasons behind the discrepancies in the statistics include the rule, which is also present in other legal systems, that in the case of crimes involving several punishable offences only the offence that is subject to the most severe penalty is taken into account (for example, in the case of a robbery motivated by anti-Semitism only the crime of robbery is taken into account). The statistics are also affected by the divergent number of events reported during rallies. Commonly, only a portion of offences committed during rallies is registered by the police and included in the statistics. In addition, the police do not always recognise the background of these crimes and categorise them as politically-motivated crimes perpetrated by right extremists, without pointing to anti-Semitism as their motivation. Another problem lies in the internal categorisation of anti-Semitic crimes, according to which whenever the crime is thought to have been committed by unknown perpetrators it is categorised as a manifestation of right extremism (based on the right extremists’ ideological affiliation to national socialism). The majority of such cases are crimes involving dissemination of propaganda materials and symbols of organisations that have been considered unconstitutional. This constitutes the largest share of all such crimes (motivated by anti-Semitism), which results in a partial distortion of the statistics.

The ‘grey area’ of crimes based on anti-Semitism also includes those that remain unreported by the victims. According to research conducted by the FRA in 2012 and by the council of experts on anti-Semitism appointed by the interior ministry in 2016, a mere 28% and 23% of surveyed German Jews, respectively, admitted to having reported crimes they had been the target of to the police. Moreover, law enforcement bodies tend to ignore some of the offenses, i.e. those that do not target specific individuals (for instance, those involving the display of banned symbols). A mere 2% of the surveyed individuals admit that the investigation undertaken to prosecute the crime they had been the subject of was launched on the initiative of the police. The categorisation of crimes motivated by the Israeli-Palestinian conflict is another problem. These offenses are categorised, depending on the officer responsible for registering them, either as crimes motivated by anti-Semitism or as “intrastate conflicts” without any anti-Semitic aspect.

The political fight

The dispute over the attitudes among political parties towards anti-Semitism is a persistent aspect of Germany’s discourse and political conflict. In recent years, it has intensified due to an unprecedented number of anti-Semitic statements by representatives of AfD, which, alongside the Left Party, is most frequently accused by other parties of ignoring anti-Semitism in its own ranks.

The dispute over the political parties’ attitude towards anti-Semitism is a persistent element of Germany’s discourse and political battles. In recent years, it has intensified due to ever more frequent anti-Semitic statements by representatives of the AfD.

In both cases, anti-Semitism is condemned by the party leaders, even though it remains present in statements by politicians from the parties’ radical factions. This is particularly true for the extreme wing of the AfD, known as Der Flügel (or ‘wing’ in German), which is monitored by counterintelligence. The most well-known incidents were those involving Wolfgang Gedeon from the Landtag of Baden-Württemberg, who has referred to The Protocols of the Elders of Zion, for instance, and Björn Höcke, the head of the AfD parliamentary group in the Landtag of Thuringia, who described the Holocaust Memorial in Berlin as “a monument of shame”. In most cases, the party’s executives offer an immediate denunciation of these views, although such a stance is becoming ever more divergent from what ordinary party members think. The latter’s resistance towards the proposal to hold individuals accused of anti-Semitism accountable was evident when they refused to support the motion in the Landtag of Baden-Württemberg to expel Gedeon from the party ranks. In the procedure, which was launched by the present AfD chief, Jörg Meuthen, the required majority was two thirds of the votes cast by AfD parliamentary group members. This attempt to expel the politician has led to a rift in the local party structures.

In the Left Party, anti-Semitic statements are most often interpreted in the context of criticism of Israel and of the USA. It is difficult to attribute anti-Semitic tendencies to any particular party wing, but the most active representatives come from western German federal states. Members of the party’s structures there formerly belonged to Marxist and Maoist groups that fought against “Israel’s imperialism” and its cooperation with the USA. The Left Party was the only party to refuse (in January 2018) to support the Bundestag’s motion to condemn anti-Semitism and to appoint a governmental plenipotentiary for anti-Semitism. Just as for the AfD, the Left Party became excluded by the remaining parliamentary groups from working on the motion. Formerly, the party had been known for instances such as its criticism of the speech that Shimon Peres had given in the Bundestag to commemorate International Holocaust Remembrance Day (on 27 January 2010) and for the participation of several of its deputies (Annette Groth, Norman Paech, Inge Hörger) in the voyage of the so-called Freedom Flotilla organised by pro-Palestinian activists, which came under attack from the Israeli Navy in May 2010. In November 2008, the CDU brought about the exclusion of the Left Party from the group of co-initiators of the Bundestag’s declaration condemning anti-Semitism in Germany. The Left Party has instead adopted the same text in a separate declaration. At present, it is being criticised for its continued support for the Gilets Jaunes, the ‘yellow vests’ movement in France, in spite of reports suggesting that the French protesters were involved in anti-Semitic incidents.

Despite the fact that anti-Semitic rhetoric is present in both parties, both the Left Party and the AfD emphasise that within their ranks there are groups that cooperate with Jews.

The increase in the number of anti-Semitic attacks is a blot on Germany’s image as a state that effectively combats any signs of anti-Semitism. This is particularly important for Germans due to historical reasons and a prevailing opinion within German society that the country has come to terms with its Nazi past in an exemplary manner.

In the case of the Left Party, this involves the Shalom task force (Bundesarbeitskreis Shalom), which has been a component of the party’s youth organisation (Linksjugend) since 2007. It tries to influence the intra-party debate on anti-Semitism, such as by organising conferences and events, as well as by issuing leaflets. A slightly different role is played by the group known as Jews in the AfD (Juden in der AfD), which was established in October 2018 by 24 party members. In its operation it focuses on prosecuting cases of anti-Semitism within the Muslim community and of left anti-Zionism. The AfD is using anti-Semitic attacks perpetrated by Muslims to criticise Angela Merkel’s migration policy by suggesting that the Chancellor is responsible for the increase in anti-Semitism in Germany (this view was expressed by the party’s deputy chief, Georg Pazderski, for example).

A blow to Germany’s image

The public debate on anti-Semitic attacks has contributed to an acceleration of the Bundestag’s work and of the German government’s actions to prevent anti-Semitism. On the initiative of the CDU, the CSU, the SPD, the FDP and the Greens, with the support of the AfD, in January 2018 the Bundestag passed a resolution condemning anti-Israeli demonstrations, the burning of Israel’s flag and anti-Semitic attacks (including those perpetrated by asylum seekers). The parliamentary debate resulted in the appointment in May 2018, for the first time in Germany’s history, of a government plenipotentiary for the fight against anti-Semitism. Diplomat Felix Klein, who in the foreign ministry was responsible for contacts with Jewish organisations and the fight against anti-Semitism, was appointed to this function. One of his priority projects is to compile an atlas of German anti-Semitism in which both anti-Semitic crimes and other incidents will be mapped. The atlas is intended to help to verify the statistics compiled by the police and to fill the gap between understated official data and the figures presented by non-governmental organisations. In one of her speeches, on 9 November 2018, Chancellor Angela Merkel also pointed to the increase in anti-Semitism and the emergence in new guises (for example, she mentioned anti-Semitism among Muslims living in Germany) and announced a plan to implement a stricter policy to combat it. In a bid to improve its image, in 2018 the German government launched a debate on anti-Semitic attacks for the first time in the history of German-Israeli intergovernmental consultations. Furthermore, at the EU level Germany will attempt to emphasise its own initiatives focused on combatting anti-Semitism. This will be one of the priorities of Germany’s EU presidency in the second half of 2020.

The increase in the number of anti-Semitic attacks is a blot on Germany’s image as a state that effectively combats any signs of anti-Semitism. This is particularly important for Germans due to historical reasons and a widespread opinion within German society that the country has come to terms with its Nazi past in an exemplary manner. Some politicians, such as the interior minister, Thomas de Maizière, treat the fight against anti-Semitism as Germany’s raison d'être and a litmus paper for German society. Similar views were expressed by Germany’s President, Frank-Walter Steinmeier. The problem is all the more serious because 40% of young Germans aged 18–34 have either never heard of the Holocaust or know “little to nothing” about it. Young people are also more prone to be critical of Israel. The new generation of pupils, who increasingly have a migrant background, is much more detached from Germany’s Nazi past, and school text books from which they learn frequently discuss the issues related to anti-Semitism in a superficial or incomplete manner. This poses new challenges for Germany, including the need to combine the country’s asylum policy and the intention to take in new migrants with the need to maintain the present special status of its relations with Israel.

Appendix 1: Actions carried out by the state to curb anti-Semitism

The increase in the number of anti-Semitic attacks has inspired the German state to launch preventive measures. This mainly concerns three areas: genuine prevention (including training sessions for teachers, police officers, judges and representatives of other professions), the system for monitoring how attacks are reported (including the proposed creation in all federal states of special units monitoring the attacks, modelled on the Berlin-based RIAS) and increased coordination of actions both in specific federal states and at the level of cooperation between the central government and individual federal states (attempts to appoint plenipotentiaries for combatting anti-Semitism in all federal states).

Due to the federal structure of the German state, mainly bodies operating at the federal state level are involved in preventing anti-Semitic attacks. These bodies include the great majority of institutions responsible for these tasks, i.e. the federal state police (protection of places of worship, schools and selected restaurants), federal state counterintelligence structures (LfV), educational institutions (including workshops organised under decentralised subsidy programmes focusing on both prevention and response to anti-Semitic attacks in schools) and federal state centres for political education (Landeszentrale für politische Bildung supervised by the ministry of the interior).

At the federation level, institutions responsible for the fight against anti-Semitism include ministries (the interior ministry in particular, as well as the ministry for family, senior citizens, women and youth) and central-level offices such as the counterintelligence office (BfV). The government’s plenipotentiary for the fight against anti-Semitism and a joint committee made up of representatives appointed by federal states and by the central government are responsible for coordination of actions carried out jointly by specific federal states and at the federation level. In addition, eight federal states have appointed their regional plenipotentiaries for the fight against anti-Semitism.

Chart 1. Anti-Semitic attacks in Germany in 2002–2017

Source: Statista.de, based on data compiled by the Federal Ministry of the Interior

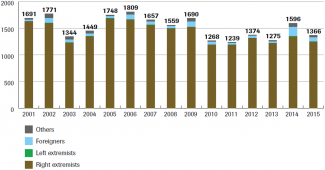

Chart 2. Attacks on synagogues in 2008-2014

Source: Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution

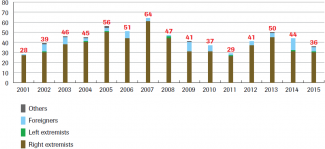

Chart 3. Politically-motivated crimes with an anti-Semitic aspect in 2001–2015

Anti-Semitic crimes involving the use of violence committed by:

Source: Federal Ministry of the Interior

[1] A speech by Federal Chancellor Dr Angela Merkel in the Knesset in Jerusalem on 18 March 2008, https://www.bundesregierung.de/breg-de/service/bulletin/rede-von-bundeskanzlerin-dr-angela-merkel-796170 (German version)

https://knesset.gov.il/description/eng/doc/speech_merkel_2008_eng.pdf (English version)

[2] K. Frymark, Napięcia pomiędzy Niemcami i Izraelem, “Analizy OSW”, 10 May 2017, https://www.osw.waw.pl/pl/publikacje/analizy/2017-05-10/napiecia-pomiedzy-niemcami-i-izraelem

[3] Der Zentralrat der Juden in Deutschland, http://www.bpb.de/politik/hintergrund-aktuell/209813/zentralrat-der-juden

[4] Jüdische Kontingentflüchtlinge und Russlanddeutsche, http://www.bpb.de/gesellschaft/migration/kurzdossiers/252561/juedische-kontingentfluechtlinge-und-russlanddeutsche?p=all

[5] Experiences and perceptions of antisemitism - Second survey on discrimination and hate crime against Jews in the EU, December 2018, https://fra.europa.eu/en/publication/2018/2nd-survey-discrimination-hate-crime-against-jews

[6] Experiences and perceptions, op.cit., Diskriminierung und Hasskriminalität gegenüber Juden in den EU-Mitgliedstaaten, November 2013, https://fra.europa.eu/sites/default/files/fra-2013-discrimination-hate-crime-against-jews-eu-member-states_de.pdf

[7] “No-Go-Areas“ in der Stadt: Wo Kippa tragen als gefährlich gilt, “Frankfurter Neue Presse“, 14 August 2018, https://www.fnp.de/frankfurt/no-go-areas-stadt-kippa-tragen-gefaehrlich-gilt-10368715.html and F. Hackenbruch, Für Juden ist jede Ecke Berlins potenziell gefährlich, “Der Tagesspiegel“, 13 December 2018, https://www.tagesspiegel.de/politik/antisemitismus-fuer-juden-ist-jede-ecke-berlins-potenziell-gefaehrlich/23743012.html

[8] Since 2017, the interior ministry has divided its statistics of crimes into new categories, among other reasons due to anti-Muslim motivation of crimes Cf. Politisch Motivierte Kriminalität im Jahr 2017, Ministry of the Interior, Construction and Heimat, https://www.bmi.bund.de/SharedDocs/downloads/DE/veroeffentlichungen/2018/pmk-2017.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=4

Politisch Motivierte Kriminalität im Jahr 2018, Federal Ministry of the Interior, Berlin, 14 May 2019, https://www.bmi.bund.de/SharedDocs/pressemitteilungen/DE/2019/05/pmk-2018.html

[10] In 2001, the interior ministry changed the definition of politically-motivated crimes, which has made it possible to include a bigger number of anti-Semitic attacks in the statistics.

[11] E. Kagermeier, Antisemitismus an Schulen: "Schon wieder Holocaust?", “Die Zeit“, 12 September 2018, https://www.zeit.de/gesellschaft/schule/2018-09/diskriminierung-antisemitismus-rechtsextremismus-juden-schulen-mobbing

[12] Ein Bericht der Recherche- und Informationsstelle Antisemitismus Berlin (RIAS), Berlin 2019.

[13] Ibidem.

[14] Ibidem.

[15] A. Zick, A. Hövermann, S. Jensen, J. Bernstein, Jüdische Perspektiven auf Antisemitismus in Deutschland, April 2017, https://uni-bielefeld.de/ikg/daten/JuPe_Bericht_April2017.pdf

[16] Germany is trying to curb hate speech on the Internet. Cf. K. Frymark, K. Popławski, ‘Germany: Combating disinformation and hate speech on the Internet’, “OSW Analyses”, 12 April 2017, https://www.osw.waw.pl/en/publikacje/analyses/2017-04-12/germany-combating-disinformation-and-hate-speech-internet

[17] M. Schwarz-Friesel, Langzeitstudie „Antisemitismus 2.0 und die Netzkultur des Hasses, Technische Universität Berlin, July 2018, https://www.linguistik.tu-berlin.de/menue/antisemitismus_2_0/

[18] D. Poensgen, A. Rasumny, B. Steinitz, D. Streibl, Problembeschreibung: Antisemitismus in Bayern, Recherche- und Informationsstelle Antisemitismus, August 2018.

[19] M. C. Schulte von Drach, Wie verbreitet ist Antisemitismus und von wem geht er aus?, 14 April 2018, https://www.sueddeutsche.de/politik/juden-in-deutschland-wie-verbreitet-ist-antisemitismus-und-von-wem-geht-er-aus-1.3921657

[20] D. Feldman, Antisemitism and Immigration in Western Europe Today. Is there a connection? Berlin, April 2018.

[21] Antisemitismus in Deutschland – aktuelle Entwicklungen, Federal Ministry of the Interior, April 2017, https://www.bmi.bund.de/DE/themen/heimat-integration/gesellschaftlicher-zusammenhalt/expertenkreis-antisemitismus/expertenkreis-antisemitismus-node.html

[22] Experiences and perceptions of antisemitism, op. cit.

[23] Jüdische Perspektiven, op. cit.

[24] Antisemitismus in Deutschland, op. cit.

[25] S. Unsleber, Verletzt in Berlin, “Die Tageszeitung“, 15 February 2018, https://taz.de/Antisemitismus-in-Deutschland/!5482392/

[26] Antisemitismus in Deutschland, op. cit.

[27] The interior ministry’s experts have also categorised as the most explicit anti-Semitic statements expressed by AfD members those made by: Peter Ziemann, Jan-Ulrich Weiß, Gunnar Baumgart. Cf. Antisemitismus in Deutschland, op. cit.

[28] Grundsatzerklärung der Bundesvereinigung Juden in der Alternative für Deutschland, https://www.j-afd.org/grundsatzerklaerung

[29] G. Pazderski, Muslime dürfen ihren Antisemitismus nicht in unserer Gesellschaft verbreiten, 23 March 2018, https://www.afd.de/georg-pazderski-muslime-duerfen-ihren-antisemitismus-nicht-in-unserer-gesellschaft-verbreiten/

[30] The word Jew was not a common insult when I went to school... it is now, CNN, 28 November 2018, https://edition.cnn.com/2018/11/28/europe/germany-anti-semitism-education-intl/index.html?utm_content=2018-11-28T07%3A30%3A12&utm_term=link&utm_source=fbCNN&utm_medium=social&fbclid=IwAR2rkY1wAzmXdaZjxLqtYnmgZhCr3oB8UaS4JfbtiyAAzWqRE43toO9620

[31] S. Salzborn, A. Kurth, Antisemitismus in der Schule, Erkenntnisstand und Handlungsperspektiven. Wissenschaftliches Gutachten, January 2019.