How the COVID-19 pandemic will develop in Ukraine

According to data compiled by Ukraine’s Ministry of Health, by 27 March more than 200 cases of COVID-19 were confirmed nationwide, with five fatalities. However, there is a risk of the epidemic soon developing on a much larger scale. This is due to the high daily increase in the number of infections diagnosed, the unpreparedness and inefficiency of the healthcare sector, the shortage of medical equipment, the ongoing dispute in the Ministry of Health, and the organisational and financial weakness of the Ukrainian state combined with of the ruling elite’s limited experience of governance. At the present stage, the possible consequences of the pandemic are difficult to forecast. However, it is certain that Ukraine will see a deep recession (the most optimistic forecasts spell a 5% drop in Ukraine’s GDP in 2020).

The characteristics of the epidemic in Ukraine and the reaction of the authorities

At present, in Ukraine there are three hotspots of COVID-19: in the Chernivtsi region bordering Romania (47 individuals diagnosed with the disease), in Kyiv and the Kyiv region (a total of 79 cases) and in the Ternopil and Ivano-Frankivsk regions in western Ukraine (49 cases). In 13 regions isolated cases (1–9) have been recorded and in seven other regions no individuals have as yet been reported as being infected with the virus. The reason behind the low reported incidence rate is the low number of tests performed. Although no consolidated nationwide statistics are available, on 23 March the Population Health Centre announced that a mere 850 tests had been performed. This figure should increase due to the number of tests performed by private and regional laboratories, but this number is insignificant (for comparison, by 26 March Poland had performed more than 26,000 tests). On 23 March, Ukraine received 250,000 rapid tests and 521 laboratory test kits from China. Further batches of tests are expected to arrive at the end of this week.

Regardless of doubts concerning the efficiency of the rapid tests, it should be expected that the next couple of days will see a major acceleration in the speed of the diagnostic procedures performed to spot new cases of the disease. In Ukraine, one factor facilitating the spread of the virus is the belated and poorly thought out response of the authorities to curb the transmission of the virus (e.g. the closure of Kyiv’s metro system which resulted in commuters crowding into buses). In addition, over the last two weeks a portion of Ukrainian economic migrants (no precise statistics are available) returned home, including from Italy and Spain. The available information suggests that not all of them were examined by a healthcare professional upon their arrival, and many failed to comply with obligatory self-isolation.

Surprised by how quickly the virus was spreading in Europe, the Ukrainian authorities launched delayed efforts to improve the current crisis management system. Although Ukraine’s first case of the novel coronavirus infection had been recorded on 3 March, the government adopted a plan involving fighting the spread of the virus as late as 11 March. The announced measures were connected with the need to procure medical equipment and personal protective equipment and to include these in the state’s strategic stockpile. In addition, the first preventive measures were introduced to tighten checks at border crossings. Nationwide coordination of these activities was entrusted to an anti-crisis team modelled on the State Commission for Technogenic and Environmental Safety and Emergency Situations. The commission includes members of government, regional governors and the CEOs of major state-controlled companies. On 14 March, Ukraine’s president signed a decree on the enforcement of a resolution by the National Security and Defence Council of Ukraine (NSDC) regarding the launch of immediate actions to ensure national security in the context of the spread of the virus. Since then, the government’s activities in this field have been supervised by the president. The proposed solutions are being implemented in the form of recommendations issued by the NSDC and are then approved by the president. The Security Service of Ukraine (SBU) has focused its activities on counter-intelligence and cyber security measures. On 25 March, the government declared a state of emergency across Ukraine (not of the highest level). It will remain in place until 24 April and may be extended depending on the assessment of the epidemiological situation. In practice, this is tantamount to stepping up public order protection measures (including surveillance of individuals in quarantine), restrictions on the free movement of citizens (no public transport between cities, a maximum of 20 passengers in a vehicle within cities, and the metro systems in Kyiv, Dnipro and Kharkiv have been shut down), and public health and disease prevention services stepping up their disease control measures. The state of emergency enables the government to introduce further restrictions including a ban on citizens gathering in public places and recommendations for residents to avoid crowding in commercial facilities. The state of emergency does not allow for civil rights and freedoms to be curbed, for limits to be placed on the freedom of engaging in political activity, or for the state to take over private companies.

The crisis in the healthcare sector

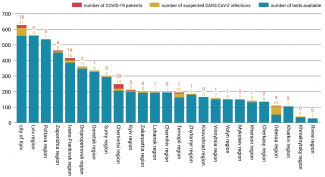

The Ukrainian healthcare sector is largely unprepared to face the pandemic. On 25 March, Ukraine had 6,202 hospital beds suited to the treatment of COVID-19 patients, with major differences in their availability recorded for specific regions (see Appendix). Ukraine’s surgeon general responsible for disease prevention announced that the country has a total of around 3,500 ventilators including 350 in isolation wards (their technical condition is unknown). Although plans have been made to purchase more ventilators, due to tender procedures their delivery time are likely to be extended.

For more than two decades following the collapse of the Soviet Union, the Ukrainian healthcare sector remained largely unreformed. A comprehensive reform was launched as late as 2017 with the implementation of a package of reform laws. The first stage of the reform covered primary healthcare and for example envisaged the introduction of the “money follows the patient” rule, the establishment of a special agency known as the Medical Procurement of Ukraine responsible for purchasing medical products at the central level, the appointment of general practitioners, the introduction of online appointment booking systems and electronic prescriptions. To date, secondary and tertiary healthcare has remained unreformed (this stage of the reform was planned to be launched in spring 2020). In addition, since the 2019 change of power in Ukraine, the Ministry of Health has been experiencing ongoing competence disputes, personal conflicts and suspicions of corruption, which – combined with the reform currently being implemented – is exacerbating the chaos in the healthcare sector. Recent days have seen the dismissal of the Minister of Health Ilya Yemets, who was only appointed on 4 March (he remains in office). In addition, information was leaked to the media suggesting a major conflict between Yemets and the director of Medical Procurement Arsen Zhumadilov. Zhumadilov, who was appointed in an open competition, accused the minister of demanding that a candidate indicated by him should be appointed as deputy director. Moreover, according to Zhumadilov, the minister allegedly attempted to bribe him. The conflict resulted in the blocking of the launch of the central-level procedure to purchase medical equipment and supplies, including those that can be used to combat COVID-19. At present, local government bodies and entrepreneurs are involved in purchasing medical equipment, which results in lack of credible statistics regarding its number and availability.

The political factors hampering the effective fight against the pandemic

As a result of the political changes that happened in 2019, key offices in the state administration, excluding the Interior Ministry, were assumed by individuals with no political experience. As he became Ukraine’s top politician, President Volodymyr Zelensky believed that these officials would ensure that corruption within the ruling elite would be eliminated. The government reshuffle performed in March 2020 proved that the president had revised his views to a certain degree. However, the new government headed by Denys Shmyhal can hardly be viewed as a cabinet made up of reliable and experienced professionals. Therefore, it should be assumed that during the period of the pandemic, which in itself is a unique test of the government’s efficiency and the effectiveness of cooperation between ministries and local administration bodies, the Ukrainian authorities will make mistakes and the effectiveness of their activities will be limited.

Frequently, decisions regarding the fight against COVID-19 taken at the central level are being sabotaged and ignored by specific regions. This is due to the fact that the most recent local elections in Ukraine were held back in 2015 and the authorities elected in 2019 have either had too little time to consolidate their power at the regional and county level or have ignored the need to do so. Not all of the regional government heads (the so-called governors) have been appointed by the present president – in some regions they have already been replaced twice. Another problem is posed by the need to appoint officials at the county level, where many posts are vacant and some continue to be filled by individuals appointed by the former president. In addition, the new regional authorities were not always able to find a common language with the local elite – both the business elite and e.g. mayors of major cities. One example is the Kharkiv region in eastern Ukraine, where actions carried out by the regional governor have been openly criticised by strong regional actors including the mayor of Kharkiv Hennadiy Kernes and influential businessman Oleksandr Yaroslavsky. In the conflict which has been ongoing in this region, the president sided with businessmen and threatened to dismiss the governor should the latter fail to reach a compromise with Yaroslavsky. In the regions, real power is held not by politicians associated with President Zelensky’s political camp but by politicians associated with opposition parties (including European Solidarity led by former president Petro Poroshenko and Batkivshchyna led by Yulia Tymoshenko), as well as by businesspeople sceptical of the new authorities. This has already triggered conflicts and rivalry. Moreover, it suggests that Kyiv’s decisions will only be enforced to a small degree.

President Zelensky is attempting to consolidate his power in the regions by launching direct cooperation with big business and oligarchs. On 16 March, he held a meeting in his office with 15 businessmen (including Ihor Kolomoysky and Rinat Akhmetov). The president intended to raise non-public funds for the fight against the pandemic, to arrange for the additional import of medical equipment, tests and face masks, and to transfer a portion of the control of specific regions to the oligarchs. According to the very few press accounts of the meeting, each businessman was granted control of one or more regions depending on the location of his most important business assets. The information available suggests that the cooperation between the president and the businessmen has no official framework, which means that it is unclear whether the state will be expected to compensate them for the costs they will bear and, if so, how. The arrangements made with the oligarchs are proof of the state’s minor effectiveness in coping with the challenges posed by COVID-19. They also confirm the key role this group is playing in the Ukrainian system of power. In the coming years, this cooperation will reduce Ukraine’s prospects of de-oligarchisation. However, in the short term, its effects in the fight against the pandemic are likely to be positive. To date, the president has managed to raise additional funds and managers associated with local business tycoons joined the regional crisis management teams. It has also been reported that Yaroslavsky’s contacts with Jack Ma, the head of Alibaba Group, along with the funds offered by big business, made it possible to purchase medical equipment from China. The first batch of this equipment arrived in Ukraine on 21 March.

According to announcements by the so-called authorities of the Donetsk and Luhansk People’s Republics (DPR and LPR), by the end of March no instances of the SARS-CoV-2 infection have been recorded there. However, no information on the tests performed is available (it was announced on 18 March that a mere four tests had been performed). The delayed introduction of quarantine for residents of these self-proclaimed republics and the introduced restrictions (reduced or banned traffic at crossing points on the so-called demarcation line with Ukraine and the border with Russia) indicate that the threat is being downplayed. This results in the residents’ reduced discipline in complying with quarantine (bars and restaurants, shopping malls and open-air markets are operating) and the absence of sufficient checks and protection of individuals crossing the demarcation line between Ukraine and the DPR/LPR. The increased incidence rate of swine flu and acute upper respiratory tract infection recorded in recent weeks raises doubts regarding the actual number of individuals infected with the novel coronavirus. It should be assumed that in the territory of the two breakaway republics there have been SARS-CoV-2 infections, however, they have not been confirmed to date due to the irresponsible policy of the so-called authorities and the insufficient number of tests performed. The demographic structure of the occupied areas, which includes a large number of senior residents, increases the risk of an epidemic developing there.

Outlook

It is difficult to clearly forecast the possible development of the epidemic in Ukraine. However, it seems that it is likely to develop on a scale comparable to that recorded in Western Europe. The example of big EU countries demonstrates that, once the number of infections exceeds 100, the increase in the number of new cases diagnosed accelerates significantly. In Germany, the number of infections reported two weeks after this threshold had been crossed was 4,600, three weeks on it was more than 22,000. The corresponding figures for Spain are 7,800 and 28,800, and for Italy – 5,900 and 22,000. Ukrainian hospitals are not prepared to take in such large numbers of infected patients and the expected qualitative and quantitative change in their equipment base will not happen over the next two or three weeks. Other epidemics, e.g. of tuberculosis and measles, are another factor increasing the burden shouldered by the healthcare sector. This, in turn, may trigger an increased mortality rate among COVID-19 patients.

Yet another challenge is posed by the spread of fake news, which may provoke social unrest. Representatives of the SBU point to Russia as a state which is engaging major resources to carry out disinformation activities targeting Ukrainian society. The effectiveness of the government in Kyiv will depend on its capability to enforce the solutions it has introduced. The actions carried out to date have demonstrated that the state administration is unable to carry out all of its tasks. Another challenge is posed by the need to enforce discipline and discourage residents from ignoring the recommendations, e.g. the laws restricting freedom of movement.

It should be expected that the Ukrainian economy will suffer very serious consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic. In recent months, Ukraine has seen a gradual economic decline caused for example by stepped up protectionist measures on the part of the US, the EU and the Middle Eastern states. These measures are affecting the Ukrainian metallurgical sector. In February the country’s GDP declined by 0.5%, the volume of industrial production has been shrinking since October 2019 (including by 5.1% in January and by 1.5% in February 2020). At present, optimistic forecasts for 2020 spell a 5% decline in Ukraine’s GDP. Should the global pandemic last longer, it cannot be ruled out that Ukraine will be hit by a recession similar to the one that happened in 2009, when the country’s economy shrank by 14.7%.

One method to mitigate the consequences of the crisis is to immediately adopt a new programme of cooperation with the International Monetary Fund. Although a preliminary agreement was reached in December 2019, Ukraine has failed to meet its two main conditions to be able to receive the first loan instalment. These conditions required Ukraine’s Verkhovna Rada to enact a law enabling the sale of farmland and a law to prevent the situation in which banks formerly been owned by oligarchs and nationalised in 2014–2016 could be returned to their former owners or that compensation could be paid by the state to these former owners. This particularly concerns PrivatBank, formerly owned by oligarchs Ihor Kolomoysky and Hennady Boholyubov. Kolomoysky, who controls both one faction in the Verkhovna Rada and a group of MPs who are members of the ruling Servant of the People party, has successfully blocked the adoption of this law. The vote is planned to take place during an extraordinary parliamentary meeting. However, it is not known when this meeting will be held or whether the number of votes cast will be sufficient to enable the adoption of the law. Previously, Prime Minister Shmyhal spoke clearly in favour of resuming cooperation with the IMF as soon as possible. On 26 March, Kristalina Georgieva, the IMF’s Managing Director, announced that if it meets the requirements, Ukraine can hope to receive support exceeding the US$ 5.5 billion agreed in December.

Declining economic migration will be another problem for Ukraine. It is certain that this will happen, although at this point it is difficult to estimate on what scale. In 2019, Ukrainian economic migrants sent around US$ 12 billion in remittances alone to Ukraine, which accounts for around 9% of the country’s GDP. Any decline in these remittances will not only affect millions of Ukrainian families, but will also pose a major problem for the state’s balance of payments and form another factor contributing to the weakening of the hryvnia.

APPENDIX

Chart 1. The situation in hospitals in specific regions (as on 25 March)

Source: Department of Regional Policy and Decentralisation at the Office of the President of Ukraine.

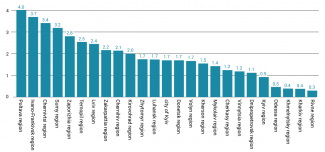

Chart 2. Number of dedicated hospital beds in specific regions per 10,000 inhabitants (as on 25 March)

Source: Department of Regional Policy and Decentralisation at the Office of the President of Ukraine.