The act on the land market – a key step towards the development of Ukrainian agriculture

On 28 April, President Volodymyr Zelensky signed the Act on introducing an agricultural land market in Ukraine. The document envisages that the moratorium on the sale of agricultural land will be partially lifted on 1 July 2021 and entirely lifted from 2024. As a consequence, for the first time in the history of independent Ukraine, the free trade of agricultural land will be allowed. However, foreigners and even Ukrainian companies foreign shareholders will not have the right to buy land until a nation-wide referendum concerning this issue has been held. Regardless of certain reservations as to the wording of the act, the fact that it has been passed is a breakthrough moment for Ukraine. These reservations for example relate to the risk that antitrust provisions may be bypassed and also to the need to enact a number of laws and to implement acts regulating the practical operation of the land market. It should not be expected that major changes in the ownership structure of agricultural land will happen on a large scale by 2024. However, the act will have far-reaching consequences for Ukrainian agriculture in the mid- and long-term perspective. It will enable increased production and facilitate development in those sectors which are currently underinvested. It is also expected to improve the position of small and medium-sized agricultural companies[1] at the cost of big agricultural holdings and to boost the status of Ukraine as one of global leaders in the production of foodstuffs.

Historical background

In the Soviet era, the state was the exclusive owner of land. Agricultural businesses (kolkhozes and sovkhozes) enjoyed the right to use land free of charge and for an indefinite period, whereas the buildings situated on this land, the machines and other movable items were their own property. Small allotment gardens – tiny farms that the kolkhoz employees were allowed to use for personal purposes – were a portion of land used by the specific kolkhoz. Soviet-era Ukraine was dominated by farms performing extensive land management, i.e. kolkhozes (production cooperatives) and sovkhozes (state-owned companies). In 1990, there were around 8,000 kolkhozes in Ukraine and around 3.8 million kolkhoz workers. Small allotment gardens cultivated using intensive farming methods and sometimes using horticultural methods accounted for 29.6% of agricultural production including 48.1% of animal production.[2]

In 1992, a law was enacted to reform the kolkhozes. It did not abolish them but granted the kolkhozniks the right to obtain a portion of their kolkhoz’s land which had been allotted to them (a so-called pai). The law did not envisage delimiting these plots of land in the field and on the maps (they were to be delimited only when the owner of a specific pai intended to leave the kolkhoz and farm their land on their own). Due to the fact that this process solely covered land, the kolkhozniks were expropriated of their shares in most of the kolkhoz property, i.e. buildings, machines and assets belonging to the cooperatives. This considerably facilitated the privatisation of kolkhozes.

The process of determining the size of specific pais (1–8 hectares depending on the region) lasted ten years. It involved determining the area of land allotted to each kolkhoznik and issuing a relevant certificate (the pai certificate) showing its holder’s share in the land used by the kolkhoz. The process of dividing the land into pais covered the entire land owned by cooperatives, and certificates confirming their holder’s right to obtain a pai were issued to 6–8 million individuals, according to various figures. The vast majority of these certificates were leased to executives of agricultural companies or brought as a contribution in kind to the companies they managed; only approximately 6% were transformed into the right to use a specific physically delimited plot of land.

The introduction of the moratorium and its consequences

In 2001, a land code was adopted in Ukraine which introduced property rights to agricultural land. At that time it was decided (not without reason) that the country was not ready to introduce free trade in agricultural land, for example due to there being no land cadastre register. As a consequence, the introduction of free trade in agricultural land was suspended (according to Ukrainian legal nomenclature it was covered by a moratorium) until the necessary conditions are met.

The suspension of the right to buy and sell agricultural land was prolonged annually until 2019 for political and social reasons (see below). In the meantime, two highly important processes happened. The first one involved the concentration of agricultural land and resulted in the creation of the so-called agro-holdings or companies performing their farming activity on tens or even hundreds of thousands of hectares leased from pai owners. Ukraine’s ten biggest agro-holdings lease a total of 2.8 million hectares of land.[3] The owners of these companies have gradually become one of the country’s major groups capable of exerting political pressure, alongside oligarchs operating in heavy industry.

The other process involved the former kolkhozniks dying out, many of them heirless, which resulted in the emergence of pais that have not been inherited and were frequently used by the owners of agricultural companies non-contractually (the area of these pais is estimated at 1.6 million hectares and this figure is rapidly growing). The practice of using these plots of land free of charge was an important motivation to prevent the introduction of the reform to deal with the ownership situation in agriculture.

The absence of land ownership rights has contributed to the emergence of a unique model of agriculture in Ukraine, which is oriented towards obtaining the maximum profit in the short term with minimum outlays. Agricultural production is dominated by cereal and oil crops, whereas the sectors that require more significant outlays (such as the cultivation of perennial plants and animal husbandry) and the food processing sector remain much less developed, even though they generate a much higher profit in the long term. This results from a reluctance to carry out long-term investments on leased land. In addition, due to the absence of land ownership, companies using this land rarely care about using it properly, which results in soil productivity becoming degraded.

Despite the unique model of land use, recent years have seen a dynamic development of agriculture in Ukraine. For example, between 2015 and 2019 sunflower crops increased from 11.2 to 15.3 million tons, wheat crops from 26.5 to 28.3 million tons and maize crops from 23.3 to 35.9 million tons. Agriculture has become the driving force of foreign trade, overtaking metallurgy. In 2019, Ukraine’s export of foodstuffs and agricultural produce stood at US$ 22.1 billion and accounted for 44.2% of its total exports, whereas the export of metallurgical products stood at US$ 10.2 billion (20.5% of total exports). As a consequence, Ukraine has become one of the major players on the global agricultural produce market. According to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), Ukraine is the world’s top exporter of sunflower oil and a major exporter of wheat (5th place), maize (4th place), rapeseed (3rd place) and barley (3rd place).[4]

Political games with the moratorium

Almost as soon as the moratorium was introduced in Ukraine, debates were launched about lifting it and on introducing free trade in agricultural land. This solution was mainly supported by liberal free market-oriented groups but their voice was always marginal. In addition, Ukraine’s cooperation programme with the International Monetary Fund signed in 2014 contained a requirement that the moratorium should be lifted. However, until recently it was never viewed as a necessary condition for Ukraine to receive new loan instalments.[5] The IMF never recommended any specific shape the agricultural reform should take, nor did it demand that foreigners should be allowed to buy land in Ukraine.

The main opponents of the plan to lift the moratorium included nationalist groups which view land as a basis for the nation’s existence, alongside populist groups which capitalise on pointing to the threat that national property may be sold off. The latter groups include the Batkivshchyna party led by Yulia Tymoshenko and the Radical Party of Oleh Lyashko. The attitude of the populists resulted from the fact that the plan to lift the moratorium is supported by a minor portion of society. Back in February 2020, a Razumkov Centre poll showed that a mere 19.6% of Ukrainians supported the introduction of free trade in agricultural land and as many as 64.4% were opposed to it. Such a high proportion of respondents who are opposed to this change results from their fear of a repeat of the situation in the 1990s involving the privatisation of state property. Back then, most profitable companies and industrial plants were taken over by a group of oligarchs for a minor portion of their market value. There were also fears that inhabitants of rural areas may be exposed to the social consequences of large agricultural companies acquiring property rights because the income these individuals earn from leasing their pais is an important element of their livelihood. Due to this public mood, none of the political forces which were in power post-2001 viewed the introduction of free trade in agricultural land as a priority.

In addition, this status quo was favourable for powerful agro-holdings which had access to funding from other sources. Prior to the 2009 crisis, one method to obtain funds involved getting the company listed on foreign stock exchanges (five Ukrainian agricultural companies are listed on the Warsaw Stock Exchange). Other methods included: issuing bonds, taking out individual loans for big companies, and (in the case of the biggest agro-holdings) using funding opportunities offered by their own bank. These measures enabled these companies to gain a competitive advantage over smaller companies which were not in a position to use this type of instrument.

The lifting of the moratorium

The prospect of the moratorium being lifted emerged after the presidential victory of Volodymyr Zelensky. During his campaign, he had supported this solution and even included it in his programme as one of its most important elements. According to his team, the introduction of free trade in agricultural land was intended as an important stimulus boosting the development of the Ukrainian economy as a whole. Following parliamentary elections and the forming of a new majority in the Verkhovna Rada (Ukrainian parliament), a bill was submitted to introduce free trade in agricultural land. The first reading took place in November 2019. The bill sparked major controversy mainly due to the proposed very high threshold preventing land concentration (200,000 hectares) and the provision enabling companies with foreign capital to buy land. A portion of the opposition (the Batkivshchyna party and the pro-Russian Opposition Platform – For Life) attempted to block the adoption of the act by submitting more than 4,000 amendments which took four months to consider. Finally, Zelensky agreed to a compromise regarding the most sensitive issues. As a consequence, in the bill submitted for the second reading the concentration threshold was reduced, a ban on the sale of state-owned land was added and a provision was included, according to which a referendum will need to be held on the sale of land to foreign businesses and to Ukrainian companies owned or co-owned by foreign citizens. This sale will be allowed if the referendum result is positive.

Despite certain objections, including in the ruling party, on 31 March 2020 the Verkhovna Rada ultimately adopted this act. The act would have been impossible to pass if not for the support from two opposition parties – European Solidarity and Voice (as regards the governing Servant of the People party, only 206 out of its 248 MPs voted in favour of the act). The Batkivshchyna party, the Opposition Platform – For Life, and most non-aligned MPs voted against the act. On 4 May 2020, a portion of these MPs (48 individuals including Yulia Tymoshenko) filed a motion with the Constitutional Court to declare the act illegal due to procedural reasons. Consideration of this motion will likely last for several years. However, it is unlikely that the act could be annulled. In its adjudicating practice to date, the court most frequently took a loyal position towards the government in Kyiv. Despite low public support for the lifting of the moratorium, the voting has not sparked social protests.[6] Nor has the act triggered criticism from the media (including those media outlets which are owned by oligarchs). This may suggest that the adopted model of trade in land does balance out the interests of land owners, agricultural companies and the state.

Although the act’s adoption was among the necessary conditions the IMF had indicated in the context of it resuming its cooperation with Ukraine, it seems that the attitude of President Zelensky was the decisive factor in this case. Without the president’s personal involvement (the vote was held in his presence and he had called on the MPs to vote in favour of the act), the result of the vote would have been uncertain.

The provisions of the act…

The act concerns the 41.5 million hectares of land covered by the moratorium and envisages the liberalised trade in this land from 1 July 2021. A transitional period will apply for 2.5 years. During this period only natural persons will be allowed to buy land, at a maximum of 100 hectares per person. Starting from 1 January 2024, corporate entities will also be allowed to buy land and the limit will be increased to up to 10,000 hectares of land per buyer. Banks will have the right to acquire land ownership rights only if they receive it as a pledge for an unpaid loan and they will be obliged to sell it within two years. Until 2030, the selling price cannot be lower than the regulated price determined by the State Service of Ukraine for Geodesy, Cartography and Cadastre (see Appendix).

The pre-emption right will be vested in those leaseholders who leased the land in 2010 or earlier. They will be offered the opportunity to purchase the land and gradually pay it off over ten years at a price determined in a regulated valuation. This provision will also cover state-owned land (a total of 10.4 million hectares) whose sale is otherwise banned.

The right for foreigners to buy land roused major controversy. The wording of the bill submitted for the first reading included a provision which enabled this. However, due to negative political and social reactions, a requirement was added to this provision of the adopted version of the act, that a referendum must be held on this issue. The public mood in Ukraine suggests that a negative result of the referendum is certain, no matter when it is held. However, should Ukrainians decide otherwise and agree to the sale of land to foreign citizens, the buyers could not include corporate entities owned or co-owned by a foreign country,[7] Russian citizens and the following categories of companies: companies registered in tax havens, companies based in FATF-listed third countries which fail to take effective measures against money laundering, and companies whose owners cannot be identified. Regardless of the referendum result, a ban on foreigners buying land within a 50 kilometre border zone will apply. In addition, a ban on altering the ownership structure of land located in the Autonomous Republic of Crimea and in the so-called Donetsk and Luhansk People’s Republics was introduced.

...and numerous doubts

There are several aspects in which the adopted document is vague and in which it refers to detailed provisions to be enacted in separate legal acts in the future. One such aspect involves the 10,000 hectare land ownership limit. Although the details of this limit were agreed during the second reading, it seems that it will be possible to bypass the limit by registering land as to the property of family members, which would make it possible to concentrate up to around fifty thousands of hectares in the hands of a single owner. For the vast majority of agricultural companies this will be a sufficient area to maintain the current level of their operations – at present a mere ten to twenty agricultural holdings lease areas in excess of 50,000 hectares.

It is unclear how the ban on land concentration will be enforced in practice. According to the act, detailed rules of supervision in this field will be defined in a separate government order. In line with the act, the notary public who draws up a specific contract will be required to check in the relevant register whether the given individual or entity is allowed to buy land. In Ukrainian conditions, this poses a major risk of corruption. It cannot be ruled out that giant agricultural holdings will make attempts to illegally purchase land through a network of their subsidiaries or bribed natural persons (so-called frontmen). However, this practice will offer no guarantee of land ownership in the long term – if it is revealed that an area of more than 10,000 hectares was purchased or that the purchased land is de facto owned by a non-eligible individual (e.g. it is inherited), the owner will be required to sell the land within a year. Otherwise, the land will be confiscated from them pursuant to a court decision and sold by tender. The money earned from this sale minus the court costs will be transferred to the land’s former owner. The ban on non-Ukrainian companies buying land will affect local companies listed on foreign stock exchanges and companies owned and co-owned by foreign entities. It remains to be seen whether these companies will find a way to circumvent this provision.

At present, it is difficult to assess the practical aspect of the process of changing the land ownership structure. There is a risk that there may be numerous cases of the illegal excessive concentration of land. The situation will depend on whether the register of corporate entities, the land cadastre register and the property register are effectively combined. Although the act does contain a provision on increasing the exchange of information between these registers and the technical aspect of their full synchronisation seems relatively easy, it remains to be seen whether the Ukrainian leadership will be willing to guarantee full transparency of land ownership.[8]

Another question with no easy answer regards whether companies have sufficient funds to buy vast areas of land. Should a mere 10% of Ukraine’s total amount of agricultural land be sold at a regulated price (in Ukraine this is US$ 1,000 per one hectare of land on average), this would be tantamount to an expense of more than US$ 4 billion, which is an extremely high amount by local standards. In addition, sociological research shows that a mere 7% of land owners will be willing to sell their property.[9] The act envisages the preparation of a plan to provide financial support to natural persons and farms intending to buy land, however, it is uncertain whether the programme could enable a large-scale lending activity.[10] Although in theory giant agricultural holdings have more opportunities to take out a loan, a major portion of them are in debt and are unlikely to be able to find funds to buy vast areas of land in a short time. Therefore, it should be expected that the process of land ownership change will be spread over many years.

The final wording of the act has failed to impose a restriction on the concentration of land in one territorial entity to 33%. With the 10,000 hectare limit already in place, imposing such a restriction at the regional level would be pointless. However, this change means that in the case of smaller territorial entities (hromadas, or communes), a single buyer will be able to buy all the agricultural land located in this area.

Finally, there are serious doubts regarding the provision granting the pre-emption right to the leaseholder of a specific plot of land. This is limited to lease agreements signed in 2010 or earlier. Private owners will be required to sell land to the leaseholder only when no other potential buyer offers a higher price. The issue of buying state-owned land, which would otherwise be banned, remains unclear. In line with the current regulations, the leaseholder will have the right to buy it without a tender at a relatively low regulated price. There is no information concerning the area of state-owned land that would be available for this type of purchase, but it seems that this may be loophole enabling long-term leaseholders to obtain property rights at a relatively low price. While it is difficult to expect private owners to offer their land for sale below the market value, in the case of state-owned land there is a risk that this may occur. At present, it is difficult to predict how this type of transaction will be carried out in practice; detailed rules are expected to be defined in a separate act.

Outlook

The shifting of the deadline for lifting the moratorium from October 2020 (which was envisaged in the bill’s first reading) to July 2021 gives the Verkhovna Rada and the government more time to adopt additional laws, to amend the current laws and to prepare several necessary implementing acts, for example defining the rules of land auction and of keeping a land register.[11] The transitional period will enable the biggest agricultural market players to adjust to the new reality. The decision to lift the moratorium entirely as late as 2024 is justified in the context of the looming economic crisis in Ukraine caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. A rapid opening of the land market would pose a significant risk that a major portion of the land bought on loans would be taken over by banks should the buyers prove unable to repay their loans.

It is currently difficult to assess how the 10,000 hectare land ownership limit will affect the operation of the giant agricultural holdings in Ukraine. Nine of them currently lease areas in excess of 100,000 hectares, and there are dozens of others whose areas exceed 10,000 hectares. While smaller companies will likely be able to bypass the ban by registering their land as belonging to the company owner’s family members, the remaining ones will be forced to continue to lease most of their land. It is unlikely that starting from 2024 a large-scale process of buying up land will happen. However, this will depend on financial liquidity of the purchasing entities and on the market price per one hectare, which at present is impossible to predict.

Regardless of these doubts, the adoption of the act should be viewed as a breakthrough decision resolving a problem that should have been eliminated many years ago (Ukraine continues to be Europe’s single remaining country to ban the trade in land). At present, it is difficult to assess how the agricultural land market will operate following the de facto lifting of the moratorium. The situation will depend on the quality of the new laws and the implementation of acts. It will also depend on the transparency of registers and on how the new legislation will be enforced in practice. However, it seems that in the long term the adopted model is likely to become an important source of economic growth.[12] Increased access to loans will likely trigger a more dynamic development of small and medium-sized agricultural companies. This means that the process of boosting the significance of agriculture (which has been evident in the Ukrainian economy in recent years) is likely to accelerate.

In addition, the introduction of land ownership is expected to give an impetus to the development of those sectors of the economy which require more intensive investments but nevertheless generate major profits. These include fruit farming and animal husbandry, in which land ownership rather than lease is of major importance. Due to the limited capital resources of Ukrainian companies, it should not be expected that this process will be quick. The development of agriculture is likely to trigger the development of other related sectors of the economy such as food processing and the production of fertilisers. However, in this case one factor curbing this development is the unfavourable mood for investment evident in Ukraine, mainly resulting from corruption and the lack of the reform of the judiciary. In the coming years, no significant improvement of this situation should be expected.

The economic growth impetus would be much greater if foreign entities were allowed to buy land. However, this would pose the risk that they would buy a major portion of Ukrainian land. Considering the public mood, it seems unlikely that the Verkhovna Rada would support this solution. In the coming years, the adopted act will not trigger radical changes. Instead, it will provide a legal framework enabling breakthrough structural and ownership changes in Ukrainian agriculture. It should be expected that in the mid-term perspective, regardless of economic problems caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, the agricultural reform and the related investments enabling the development of agriculture will significantly boost the importance of Ukraine as one of the world’s leading producers of foodstuffs.[13]

APPENDIX

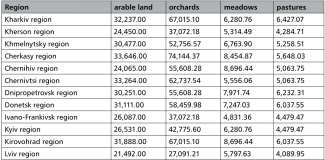

Regulated price (in hryvnias) of one hectare of land depending on its agricultural purpose in Ukraine (as on 1 January 2020)[14]

[1] Smaller companies – up to 100 ha, medium-sized companies – 100–1000 ha.

[2] T. Olszański, A quarter-century of independent Ukraine. Dimensions of transformation, OSW, Warsaw, 2017, p. 46, www.osw.waw.pl.

[3] Э. Редих, ‘Аграрные итоги маркетингового года 2018/2019’, Бизнес Цензор, 7 October 2019, www.censor.net.ua.

[5] It was not until April 2020 that representatives of the IMF directly mentioned the adoption of the act on the land market as a necessary condition for signing the new cooperation programme.

[6] Several demonstrations were held between the first and the second reading of the bill. However, they were not large-scale spontaneous demonstrations; they were most likely staged by Ihor Kolomoysky in an attempt to put pressure on the government.

[7] This is mainly intended as protection against investment funds owned by China and the Arab countries.

[8] One example showing that transparency is possible is the requirement to present the de facto owners of radio and TV stations. If this is not met the media outlets in question may be stripped of their licence.

[9] ‘Лише 7% землевласників збираються продавати пай у разі відкриття ринку’, Українські Національні Новини, 10 September 2019, www.unn.com.ua.

[10] A bill was submitted to the Verkhovna Rada envisaging the creation of a special purpose fund which is to be co-funded by international donors.

[11] The Verkhovna Rada has by now adopted some of these legal acts – for example the act on the national infrastructure of geospatial data. A portion of them was adopted at the first reading. However, due to significant amendments to the act on the land market, they will also need to be amended.

[12] Tymofiy Mylovanov, Minister of Economic Development, argued that the introduction of the land market in 2021 will contribute to a 1% increase in Ukraine’s GDP. ‘Рынок земли: Милованов рассказал, какой прирост ВВП ожидают в этом году’, Экономическая правда, 6 February 2020, www.epravda.com.ua.

[13] This mainly involves unprocessed and semi-processed products such as grain and cooking oil, rather than ready-made foodstuffs.

[14] Quoted after: ‘Оприлюднена нормативна грошова оцінка сільськогосподарських земель станом на 01.01.2020’, Ліга Закон, 16 January 2020, buh.ligazakon.net/ua.