USA – Germany – NATO’s eastern flank. Transformation of the US military presence in Europe

At the end of July, US Defence Secretary Mark Esper announced plans to withdraw approximately 12 000 US troops from Germany. Reactions in Berlin were varied. The main narrative is that of Germany being penalised and transatlantic ties being undermined. In anticipation of the US presidential election, the federal government is being guarded in its statements. The German federal states affected by the cuts have started lobbying to stop the plans. The political parties in Germany are divided in their views on the Trump administration’s decision, which is welcomed by almost half of German society. Regardless of the motives, the Pentagon’s plans show the trend in the restructuring of the US permanent military presence in Europe. US permanent forces in Europe could in future be cut further as the US is less and less engaged in the Middle East and Africa. The units being recalled from Germany will not be moved permanently to allies east of the Oder. For NATO’s eastern flank, the Pentagon is developing the concept of a flexible, scalable presence, allowing rapid reductions, but also rapid reinforcement of US forces. The changes to the US military presence in Europe are challenging for the European allies. A departure from the standard debate on the US’ withdrawal from Europe or on the NATO-Russia Founding Act is needed. The discussion is overdue on how to adapt to the transformation of the US presence with regard to collective defence within NATO, and how Europe, and not only France, should engage in crisis management in the European neighbourhood.

The US military presence in Germany in 2020

Germany currently hosts the largest permanent contingent of US troops in Europe, and the second largest in the world (see Figure 1). The concentration of US military installations in (western) Germany is a legacy of the US occupation and its strong military presence in West Germany during the Cold War. Just before the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, approximately 250 000 US troops were stationed in West Germany. Since the beginning of the 1990s, the permanent presence of US troops in Europe has been successively reduced, and stood at 112 000 in 2004. At the same time, the range of US military activities has been expanded to cover engagements outside of the European theatre.

The recent major reductions in the US military presence in Europe were made by the Obama administration. In 2013, the last US tanks left the continent, and the permanent US military presence was decreased to approximately 60 000 troops. The US Army in Europe has maintained the largest permanent contingent with two light brigade combat teams ( a Stryker brigade in Vilseck, Germany, and an airborne infantry brigade in Vicenza, Italy) and a combat aviation brigade (in Ansbach, Germany). In the US Air Forces in Europe three fighter wings (Spangdahlem, Germany, Aviano in Italy, and Lakenheath in the UK) one airlift wing (Ramstein, Germany), and one air refuelling wing (Mildenhall, UK) were left. US tactical nuclear weapons (significantly reduced after the end of the Cold War) remained in Europe as part of the NATO nuclear sharing programme, with a nuclear facility in Büchel, Germany among others. US Naval Forces Europe-Africa headquarters was placed in Naples, with the US 6th Fleet being stationed in Italy and Spain. Following the cuts made by the Obama administration, approximately 35 000 military and 11 600 civilian personnel (see Figure 2) remained in Germany.

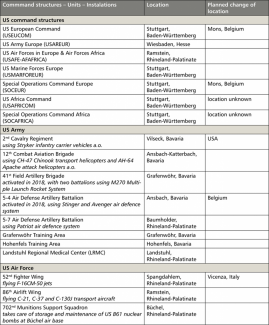

The US military presence has been concentrated in four federal states, Bavaria, Baden-Württemberg, Rhineland-Palatinate, and Hesse (see Map). Over the years, Germany became a hub primarily for the US Army, which after Obama’s cuts, maintained a Stryker brigade and a combat aviation brigade in Bavaria, along with major training infrastructure, with the largest training areas in Europe, in Grafenwöhr and Hohenfels. The training centres in these locations have been used not only by the US military, but by other NATO allies and partners as well. The US Army has also maintained large logistical, medical and intelligence facilities in Germany. In 2018, the permanent US presence in Germany was strengthened further. A field artillery brigade, with two MLRS battalions, and a short-range air defence artillery battalion were activated and deployed in Bavaria. Moreover, Germany hosts the US command structures for Europe and Africa (see Table 1). According to figures from the RAND think tank, directly or indirectly, Berlin covered 33% of the cost of US forces stationed in the country in 2002. Thus Germany was among the countries with the lowest bilateral costsharing percentage, along with Greece, Belgium, and the UK[1].

US command structures, installations, and forces have not served as a means of defence of Germany against conventional armed attack since the 1990s. The US has been using them to conduct US operations in Africa and the Middle East, including in Afghanistan, Iraq, or Libya. The Ramstein Air Base is the largest transhipment airbase for troops, cargo, and patients to and from theatres of US operations outside of Europe. In turn, the Landstuhl Regional Medical Center, located a short distance away, is the largest US Army hospital outside of the United States, and takes care of wounded soldiers coming from Iraq and Afghanistan among others.

The US forces stationed in Germany were also involved in activities on NATO’s eastern flank – in the Baltic States, Poland, Romania and Bulgaria. Since 2011, the 52nd Fighter Wing in Spangdahlem and the 86th Airlift Wing in Ramstein sends an Aviation Detachment to Łask, Poland. Since 2017, the Vilseck Stryker brigade has been rotationally providing a contingent for the NATO battle group in Poland, and has also taken part in exercises on NATO’s eastern flank, such as the 2015 and 2016 Dragoon Ride.

Berlin on reductions of US troops

At the end of July, US Defense Secretary Mark Esper announced plans to withdraw 11 900 US troops from Germany, thus reducing the US military presence from approximately 36 000 to 24 000 (see Table 1). Some parts of the command structures are to be moved from Germany (to Belgium and elsewhere), the Stryker brigade is to be withdrawn to the US, and most of the fighter wing is to be moved to Italy.

In Germany, the plans announced by the Pentagon are seen as part of the ongoing election campaign and as a move intended to penalise a country that Trump dislikes and criticises for economic expansion and ‘freeriding’ in security policy at the US’ expense. For this reason, the federal government ‘took note of this decision’, and, in anticipation of the result of the US presidential election and possible changes in the plans by Biden’s administration, adopted a cautious stance[2]. According to German commentators the plans could backfire and harm the US power projection in Africa and the Middle East, and on NATO’s eastern flank. Concerns have also been voiced about further harming transatlantic relations. In addition, Germany fears that it will become less prominent in NATO, in favour of the allies to which the withdrawn units will be moved. In Germany, a possible US permanent military presence in Poland is considered a breach of the NATO-Russia Founding Act[3] and at times a much greater challenge to the region’s security and to the cohesion of NATO than modernisation of the Russian Armed Forces, increase of their missile attack capabilities, aggressive exercises and or the military buildup in the Western Military District.

The German federal states see the reduced US military presence primarily in economic terms. The withdrawal of USEUCOM and USAFRICOM commands from Stuttgart, the Stryker brigade from Vilseck in Bavaria, and most of the fighter wing from Spangdahlem (military personnel and their families) will have a significant impact above all on the affected municipalities and counties (see Map). The US military bases meant jobs for German civilians and contracts for local manufacturers and services, as well as strengthened bilateral social and trade contacts. Even before the plans were announced by the Pentagon, the prime ministers of four federal states, from various parties (the CSU in Bavaria, the Greens in Baden-Württemberg, the SPD in Rhineland-Palatinate, the CDU in Hesse), sent a letter to thirteen influential US senators and members of Congress appealing for the plans to reduce the military presence in Germany to be stopped, as they are highly important for bilateral and transatlantic relations, for US interests, and Europe’s security.

Among the German political parties, members of the CDU/CSU and liberals are the most concerned by the US’ decision, and emphasise that the US remains Germany’s most important partner and ally outside of Europe. At the same time, they are aware of the fact that Berlin needs to invest more in its own and allied security, and also strengthen European security and defence policy. On the other hand, the chairman of the SPD parliamentary group, Rolf Mützenich, who supported in May 2020 Germany’s withdrawal from the NATO nuclear sharing programme, sharply criticised the Trump administration, and suggested that it should be called to account by cancelling plans to purchase US military equipment for the Bundeswehr[4]. The Greens did not release any statement. However, the head of the Greens’ parliamentary group tweeted that it would be better for the US to withdraw nuclear weapons from Germany than troops, and the Greens’ spokesperson for security policy stated that if US troops were to be stationed permanently east of the Oder, this would not strengthen Europe’s security and was not in NATO’s interest. The Left, on the other hand, welcomed the Trump administration’s plans, and demanded a complete withdrawal of US troops. Meanwhile, the head of Alternative for Germany (AfD) stated that the US decisions were in line with the party’s manifesto. Both the Left and the AfD pointed out that there was a need to work with Russia on European security policy.

German society is divided over the Trump administration’s plans. In a YouGov poll commissioned by the German Press Agency dpa, 32% of respondents were in favour of US troops staying in Germany (28%) or having a greater presence in Germany (4%), while 47% wished US troops to be withdrawn[5]. The highest number of opponents to the planned reductions (45%) are CDU/CSU supporters. 42% of SPD supporters, 52% of Greens and FDP supporters, 61% of AfD supporters, and 70% of supporters of the Left favoured reducing the US forces in Germany[6].

The most controversy among the public to date, apart from storage of US nuclear weapons, was caused by a satellite relay station for the US drone strikes in Africa and the Middle East located at the Ramstein Air Base. The relay station sends a signal received via fibre optics from the US to US satellites, which forward the signal to US armed drones in the Middle East or Africa. In Germany, targeted killing is considered a violation of international humanitarian law if conducted outside of armed conflicts. In March 2019, a Germany’s Higher Administrative Court found that the federal government had an obligation to ensure that any support provided by a US military base in Germany for US drone strikes complies with international law. To date, Berlin has tried to circumvent this judgment.

The US military presence and NATO’s eastern flank

The US commands and units withdrawn from Germany will not be moved to the eastern flank countries. When announcing the withdrawal of the 2nd Cavalry Regiment (approximately 5 000 troops), Defense Secretary Mark Esper said that permanent rotations of Stryker units would begin from military bases in the US to the Black Sea region. If this happens, further US troops will probably rotate mainly in Rumania and Bulgaria, strengthening the current presence of US Army on the eastern flank. Since 2016, this has been made up of rotations of an armoured brigade combat team, an aviation brigade and logistical units; approximately 6 000 troops in total. Poland became the hub for of US Army activities on the eastern flank, hosting also the US Army Division Forward Headquarters moved from Baumholder in Germany to Poznań (see Table 2). The US presence in Poland will be further strengthened in line with the Joint Declaration on Advancing Defense Cooperation of September 2019 and the Enhanced Defense Cooperation Agreement signed in August 2020.[7] The US rotational presence will be enhanced with approximately 1000 additional soldiers. Military infrastructure in Poland will be expanded with the aim to accommodate up to 20 000 US troops. Poland will host the Combat Training Centre for joint use by the Polish and US Armed Forces, the US Air Force aerial port of debarkation, facilities for the US Air Force remotely piloted aircraft squadron, for a combat aviation brigade, for a combat sustainment support battalion and for special operations forces. In addition, the forward elements of the recently activated US Army’s V Corps Headquarters are to be based in Poland. Aside from the US Army’s activities on the eastern flank, there are regular US Air Force exercises in the region (involving ground-attack aircraft, 4th and 5th generation fighter jets, and strategic bombers) and exercises of the US 6th Fleet on the Baltic Sea and Black Sea.

In addition to the rotations on the eastern flank, the US Army has been investing in prepositioning of military equipment for division-size forces in Germany, the Netherlands, Belgium, and Poland (Army Prepositioned Stock (APS) site for armoured brigade equipment is under construction in Powidz) and in modernisation of military infrastructure in Europe. In recent years, air and naval bases and training areas have been expanded in Poland, the Baltic States, Romania, and Bulgaria, as well as in Western Europe, including Germany[8]. The goal is to be able to transport troops from the US to Europe, to retrieve military equipment and ammunition from APS sites, to move US forces to the eastern flank, and to make the military infrastructure in the region ready to accommodate US forces of division size. The US DEFENDER-Europe 20 was aimed to exercise exactly this; was however limited due to the pandemic.

Regardless of the motives behind the Trump administration’s plans to withdraw some of the US troops from Germany, the transformation of the US military presence in Europe can be expected to continue. Advisors to Joe Biden have criticised the Pentagon’s plans, thus some planned measures could be put on hold if the Democratic candidate is elected. The trend, however, will continue. The US will no longer be engaged in large-scale military operations in Africa and the Middle East, and will leave to Europe crisis and conflict resolution in the European neighbourhood. Syria and Libya are examples of this. This may further impact the transformation of the US permanent military presence in Europe, including in Germany, which to date served as a hub for deploying US forces to Africa and the Middle East. At the same time, the US has been increasing its flexible engagement on NATO’s eastern flank as part of the deterrence policy, parallel to NATO’s activities in the region. The US engagement is however not about permanent military presence, but about rotating a relatively small contingent of forces that could be both quickly reduced and significantly strengthened depending on the security environment.

Withdrawal of the Stryker brigade and the fighter wing from Germany is not beneficial to the NATO eastern flank countries. This is because these would be forces that would be dislocated most quickly to enhance the rotating NATO and US troops in the region in the event of a conflict. The US military presence in Europe will however be transformed according to the interests, threats and challenges as perceived in Washington. Both the eastern flank countries and Germany need to make use of this transformation to maintain the strongest possible US-European ties and the US’ role in ensuring security in Europe. This will require an approach other than the usual discussions about US withdrawal from Europe or about the NATO-Russia Founding Act, which do not reflect the current reality and strategy. A discussion needs to be held on how, within NATO, the European allies should adapt to the transformation of the US military presence so as to maintain a credible defence and deterrence policy on the eastern flank, and whether and how Europe – and not only France – should be involved in crises management in the European neighbourhood.

ANNEX

Figure 1. Countries with the highest US permanent military presence* (June 2020)

* Does not include the National Guard.

Source: Military and Civilian Personnel by Service/Agency by State/Country

(updated: 30.07.2020), Defense Manpower Data Center, www.dmdc.osd.mil.

Figure 2. US military and civilian personnel permanently assigned to Germany (June 2020)

Source: Military and Civilian Personnel by Service/Agency by State/Country

(updated: 30.07.2020), Defense Manpower Data Center, www.dmdc.osd.mil.

Map. US Army Garrisons and US Air Bases in Germany

Source: U.S. Army Garrisons in Europe, U.S Army Europe, www.eur.army.mil; Units, U.S. Air Forces in Europe and Air Forces Africa, www.usafe.af.mil.

Table 1. US permanent military presence in Germany (June 2020)

Source: websites: U.S. Army Europe, www.eur.army.mil, U.S. Air Forces in Europe and Air Forces Africa, www.usafe.af.mil, U.S. European Command, www.eucom.mil.

Table 2. Rotational presence of US Army in NATO eastern flank countries

Source: Atlantic Resolve, U.S. Army Europe, www.eur.army.mil.

[1] M.J. Lostumbo et al., Overseas Basing of U.S. Military Forces. An Assessment of Relative Costs and Strategic Benefits, RAND National Defense Research Institute, 2013, pp. 138, www.rand.org.

[2] US announcement of changes tot he US troop presence in Germany, Joint Press Statement by the Federal Foreign Office and the Federal Ministry of Defence, 29.07.2020, www.auswaertiges-amt.de.

[3] The NATO-Russia Founding Act of 1997 regards limits on significant permanent NATO forces stationed in the new eastern member countries. The document is not legally binding, and Russia has breached nearly all of the terms of the document.

[4] Germany plans to purchase 45 F/A-18 jets and 44–60 heavy-lift cargo CH-53K helicopters (Sikorsky) or Chinook H-47 (Boeing).

[5] 25% of respondents were in favour of complete withdrawal of US troops; 10% supported the decision to withdraw, but think that 12 000 troops is too many; 9% considered the plans to be correct; for 3%, withdrawal of 12 000 troops was not enough. A large group (21%) was unable to say.

[6] A.-K. Sonnenberg, Ein Drittel der Deutschen ist gegen den US-Truppenabzug aus Deutschland, YouGov, 4.08.2020, www.yougov.de.

[7] Joint Declaration on Advancing Defense Cooperation, National Security Bureau, 23.09.2019, www.bbn.gov.pl. New U.S.-Poland Enhanced Defense Cooperation Agreement signed, Poland’s Ministry of National Defence, 15.08.2020, www.gov.pl.

[8] In addition to the US rotational presence on the eastern flank, due to the 2009 decision of the Obama administration, Poland and Romania host SM-3 interceptor and radar sites that are part of the US Aegis Ballistic Missile Defense System. At the same time, the system is the centrepiece of NATO’s missile defence.