Dangerous liaisons. A quick and coordinate withdrawal from Russian gas is proving hard for the EU

The REPowerEU proposals announced on 18 May confirm the EU’s desire to end its dependence on Russian energy. Nonetheless, it illustrates the problems associated with the process of withdrawing from Russian gas, and above all with the rapid reduction of importing it. The heavy dependence which some EU countries have on Russian gas, the persistence of very high prices and the prospect of crisis and potential shortages in the coming winter make it difficult for the EU to agree internally on a significant, coordinated reduction in supplies this year. As a result, on the one hand, intra-EU discussions about sanctions on Russian gas are very difficult and increasingly rare, while on the other hand, some restraint in the European Commission’s (EC) REPowerEU ambitions regarding the level and pace of reductions in Russian imports is becoming apparent. This weakness of the EU is being exploited by Moscow. Russian counter-sanctions, including the ‘roubles-for-gas’ demand, not only lead to divisions within the EU but also reverse the previous logic of the discussion. The majority of states and companies active on the EU market, instead of thinking about ways to limit imports of Russian gas as quickly as possible, began thinking about ways to guarantee their supplies under new conditions. Therefore, the role of the European Commission in working out common principles for EU gas relations with Russia is diminishing, in favour of the individual actions of member states, which weakens the consistency of EU action. Meanwhile, Moscow appears to be taking control of the process of reducing supplies of Russian gas to the European market. While still maintaining a significant level of exports, Moscow is also maintaining an energy weapon that it could use against the EU in the context of the approaching winter.

The EU versus the issue of Russian gas imports

The EU is heavily dependent on Russian gas and the consequences of this have been exacerbated by soaring gas and energy prices, whose impact on Europeans has been growing worse since last autumn. This is one of the factors hindering a decisive and rapid response to the Russian aggression against Ukraine. After long discussions and with difficulty (illustrated by a number of exemptions being granted), the EU managed to agree sanctions on oil imports from Russia. The topic of sanctions on Russian natural gas – where the level of dependence of both the EU as whole and of individual countries is clearly greater than in the case of oil – is even more difficult and controversial and is therefore continuously being postponed. At present, the discussion on the possibility of imposing an embargo on gas imports from Russia has de facto disappeared from the EU agenda.

There is, though, support for the European Commission’s REPowerEU plan, announced in March 2022, which envisages phasing out Russian gas imports, including a two-thirds reduction in dependence by the end of this year and a complete end to Russian imports by 2027. It is worrying, however, that already in the newest, more detailed package of REPowerEU proposals announced in May one can see a certain reduction in ambition and a lack of the necessary details for the coming months. Although the goal to become independent from Russian gas by the end of this decade is reiterated, it is no longer clear precisely when this should happen. Nor is there any clear determination to achieve the previously assumed reduction of imports from Russia by two-thirds before the end of the year. Nor is it clarified what this would exactly mean – a reduction in supplies in December 2022 compared with December 2021 or, unrealistically,[1] a 66% reduction in imports for the whole of 2022. Finally, there are no specific reduction targets agreed for individual countries, nor is the European Commission role in the process specified.

Moreover, it seems that the interest of most member states has also diminished regarding the development of joint measures, coordinated by the EC, to facilitate preparation for the coming winter and to survive the increasingly possible gas crisis. The issues related to the gas storage legislation are the single exception here – this means the obligation to have full storage capacity before the heating season and other amendments to the regulation on the security of gas supply and the regulation on conditions for access to the EU’s gas pipeline networks.[2] Apart from that there has thus far been no significant interest in the platform for joint gas purchases (Bulgaria and Greece are the only countries which clearly want to use it on a regional scale), or tangible results achieved by using this instrument. What can be seen, however, are individual actions taken by individual countries to reduce their dependence on Russian gas. There are actions by the largest importers of Russian gas in the EU, such as Germany (whose dependence, according to the government’s declaration, is to fall from over 50% to approximately 30% by the end of 2022)[3] and Italy (which has been signing further agreements on importing gas from Africa). There are also smaller states actively looking for alternative sources, such as Lithuania (which completely stopped importing gas from Russia in April), Estonia (which, together with Finland, is launching a floating LNG terminal this winter) and Slovakia (which has just signed an agreement to import gas from Norway from mid-2022 until the end of 2023).

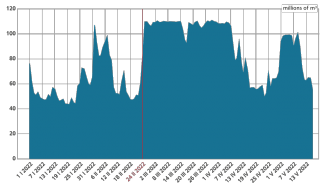

Change in the level of Russian gas supplies to the EU

Meanwhile, in the first weeks after the outbreak of the war, EU gas imports from Russia grew. As the experience of last year has shown, the limitation of gas supplies from Russia and their instability, as well as the low level in EU storage facilities (especially those owned by Gazprom), have had a strong impact on the situation in the EU market, including on prices. The war in Ukraine and the escalation of Russian-EU tensions have only exacerbated market uncertainty. Consequently, since Russia’s aggression and in the face of an increasingly unpredictable future for imports from Russia, EU companies have tried to maximise the volumes imported from Gazprom under long-term contracts and, inter alia, to fill their storage. This has resulted, paradoxically, in an increase in European gas (and oil) payments to Moscow and, with subsequent news of Russian war crimes, increased pressure from EU public opinion to stop imports. Finally, because of the stability – despite the war – of the supply of gas from Russia and its transit through Ukraine, prices on EU exchanges have fallen.

Chart. Gas transmission from Russia via Ukraine in 2022

Source: OGTSU.

In April, shipments of Russian gas to Europe began to fall. Initially, this was mainly linked to the market situation and lower, more stable gas prices (compared to those in late February and March). Later, the decrease in Russian exports also began to be affected by the EU’s increasingly difficult relations with Russia. Firstly, Lithuania announced the termination of Russian gas imports from the beginning of April. Latvia and Estonia also stopped deliveries due to the market situation. On 27 April Russia stopped deliveries to Poland and Bulgaria because Poland’s PGNiG and Bulgaria’s Bulgargaz refused to pay in roubles according to a new Russian scheme (which was contrary to the provisions of the supply contracts). On 21 May a similar situation occurred in the case of Finland, where payment in roubles was refused by Gasum.[4] Then, on 31 May, supplies to the Dutch company GasTerra ceased, and on 1 June to the Danish company Ørsted and Shell Energy Europe Limited, which has been supplying part of the gas needs of the German market. According to media reports[5] Russia also allegedly refused to accept gas payments from Gazprom Marketing & Trading at the end of April.[6] On 11 May, as a counter-sanction, it stopped deliveries to all companies in the Gazprom Germania group. These include a number of companies active on the gas trading market, such as Wingas and WIEH, through which Gazprom sold gas to customers in Germany, the UK, the Netherlands, France and Belgium (and others).[7] According to the estimates of the German Minister for the Economy and Climate Protection, the Russian counter-sanctions resulted in a decrease of Russian gas supplies to Germany by about 10 mcm per day.

Also since 11 May, due to the ongoing hostilities, the temporary loss of control over part of its territory and its gas infrastructure and, finally, incidents of unauthorised gas offtakes in the Luhansk Oblast (which is under Russian control) Ukraine has disabled transit through Sokhranivka, one of the two border points with Russia. Although transit is continuing through the larger Sudzha point, and this point’s capacity is much higher than its current use, Gazprom has refused to divert the volumes that were supposed to flow through Sokhranivka.

As a result of these factors, the total volume of Russian exports to Europe is falling. According to Gazprom, in the first five months of 2022 alone, the volume of gas sales to the so-called ‘further abroad’ countries (Europe excluding the Baltic States but also Turkey and China) fell by 27.6% y/y, with exports to China clearly growing. Since April, as a result of refusals to pay in roubles and/or individual decisions to stop imports of Russian gas, deliveries to EU countries importing a total of around 23 bcm from Russia in 2021 have been stopped.[8] In addition, the level of imports by other EU countries (including Germany) gradually diversifying their sources of supply, is decreasing and will continue to decrease.

Russian counter-sanctions a problem for the EU

At the end of May, in part due to the deadlines for the payment for Russian gas, concerns increased about the immediate future of gas supplies to the EU. The implementation of the ‘roubles-for-gas’ payment scheme and the consequences of the chosen payment model have remained unclear. The scheme itself was constructed ambiguously, which allows for different modes of its implementation for different contractors of Gazprom (as indicated by the Prime Minister of Bulgaria, for example) and for Gazprom to grant exemptions for selected companies. The necessity to open two accounts (one in euro or dollars and the other in roubles) in Gazprombank, vagueness as to whether at all, under what conditions and for which recipients a transaction can be considered completed after a payment made in euros – all creates controversy and uncertainty among EU companies. It is also an incentive for at least some European customers to seek ways of continuing to cooperate with Gazprom, as well as a tool leading to a deepening of divisions within the EU.

The problem is exacerbated by the lack of a clear, common position of the member states on the unilateral change by Russia to the conditions of payment for supplies. The European Commission has been opposed to EU companies paying for gas in roubles from the outset, claiming this would breach European sanctions imposed on Russia. In the first weeks, it has also tried to work out a coordinated, joint response to the Kremlin’s new requirements, which were contrary to the conditions of the gas supply contracts of EU consumers. However, most likely due to resistance from a number of member states and companies, the EC’s ambitions have been curtailed. The EC’s guidelines,[9] published in mid-April, were ambiguous enough to allow for mutually contradictory interpretations: some countries saw them as confirmation that they should not pay for Russian gas supplies according to the new demands, while others interpreted them as an indication there was a chance to find a compromise to pay according to the new conditions. As a consequence, on the one hand, companies from Poland, Bulgaria (and later also Finland, the Netherlands and Denmark) not only refused to pay for gas in roubles, but also failed to transfer the amounts owed in euros to Gazprombank, insisting on payment according to the conditions agreed to in the contracts; this resulted in the halting of Russian supplies to these countries. On the other hand, there were reports of other companies opening accounts with Gazprombank. Despite the appeals for unity and solidarity after the suspension of gas supplies from Russia, for example during the extraordinary EU energy council on 2 May, the differing positions of member states and the actions of European companies could not be harmonised.

Further guidelines issued by the EC in May[10] were understood by many as an instruction on how to pay for gas in euros under the Russian scheme, and a de facto green light for continued cooperation with Gazprom under the new rules. According to media reports, more than 20 EU companies intended to open accounts – only in euros or in both euros and roubles – with Gazprombank. This has led to the deepening of the division between member states of those with a more principled approach to the issue of gas cooperation with Russia during the war, including regarding payments according to the new scheme (apart from Poland and Bulgaria, this is also Lithuania, Estonia, Finland, the Netherlands and Denmark) and those who act more pragmatically (such as Austrian, German, Italian, French, Czech, Hungarian, Slovenian and Slovak companies).[11] If gas trade from Russia is not severely disrupted or broken off for other reasons during next months, this will result in growing differences, which will become apparent already in the subsequent months of 2022. Some EU countries will then still be supplied with Russian gas in a relatively stable way and at predictable prices, while others will be frantically looking for what will probably be more expensive alternatives and will have problems to close their annual gas balance and to fill storage facilities before winter. However, maintaining the only slightly reduced gas supplies from Russia to the EU means it is possible for those European countries (such as Poland or Bulgaria) whose supplies have stopped to import the missing volumes from neighbouring EU countries.

Other moves by Moscow are also a problem for the European market. The imposition of sanctions on Europol Gaz resulted in Gazprom permanently halting gas transit to Europe via the Yamal pipeline. This reduces the number of export routes from Russia to the EU, which limits the technical possibilities of increasing imports in the event of sudden surges in demand (in the wintertime, for example), and this causes a decrease in the security of supply in the EU. This is particularly important in the context of ongoing hostilities and the continuing physical threats from Russia to the sustainability of transit via Ukrainian routes. Added to this are the challenges of transit payments. In the second half of May, Ukraine’s Naftogaz reported that Gazprom had stopped paying in full for transit due to the closure of flows via one of the Russian-Ukrainian border points. This could lead to a dispute between Gazprom and Naftogaz and OGTSU which, if it does not actually disrupt transit levels (which remain low anyway), would increase tensions and uncertainty in the market.

Current challenges and the prospect of a gas crisis

There are many indications that the EU has largely lost the initiative and Russia has taken control of the process of reducing gas supplies to the European market. This refers to Moscow’s actions of recent weeks that have determined the volume of exports (including the rate of their decline) and routes. Reducing supplies will translate into smaller volumes of gas on the EU market, which will make it more difficult to fill up storage facilities and will test the solidarity of member States. The abandonment of the Yamal gas pipeline use, in the context of the permanent risk to the stability of supplies through Ukraine, increases the significance of the Russian routes Nord Stream 1 and TurkStream, and creates the opportunity for Russia to push for the launch of Nord Stream 2. In addition, by skilfully fuelling uncertainty in the market and the opacity related, for example, with the rules of supply (gas-for-roubles), the Kremlin is contributing to price rises and deepening divisions within the EU. In effect, the debate about the form of payment and other Russian actions, and uncertainty about who will continue to receive gas supplies (and on what terms), seem to have overshadowed earlier EU discussions about the options for stopping Russian gas imports altogether and reducing them rapidly already this year. Many actors in the European gas market are now more concerned with how – despite the change in payment rules – to be guaranteed supplies from Russia, rather than how to reduce these supplies.

Furthermore, while controlling the process of Europe reducing its imports of its gas, Russia has the opportunity, perhaps for the last time, to use the supply of gas instrumentally to achieve its political goals. Halting imports to Poland and Bulgaria has not inflicted a great loss on Gazprom. Neither of the two countries are among the EU’s largest consumers, nor did they wish to extend their supply contracts, which expire at the end of this year. The situation with Finland, Denmark or the Netherlands is similar. At the same time, due to this move, Gazprom has influenced the situation on the market (supporting high gas prices will result in smaller volumes being sold for more money) and – by proving its readiness to suspend supplies – the actions of other companies and EU states. Furthermore, it has so far maintained significant supplies to Europe, but these are increasingly being proceeding on Russian terms. As a result, Moscow still has the opportunity to leverage the dependence of most EU states against them. It can use gas as a weapon (e.g. in response to the recent decision on EU sanctions on Russian oil) in autumn and winter, when demand for gas will be highest, as will the vulnerability of societies and economies (and therefore politicians) to more serious supply disruptions.

It is currently difficult to forecast whether the EU will agree on measures which could significantly increase its influence on the shape of gas relations with Russia and its resilience to possible blackmail before the approaching heating season. For an increasing number of member states, the current priority challenge is not so much dependence on Russia as record high energy prices. Few of the measures taken and planned under the REPowerEU package are likely to lead to tangible results in the coming months. In the short term, the key is the new, unusually quickly agreed storage rules, which are to come into force before the heating season to help to build up sufficient gas reserves before winter.

Less clear is the future and, above all, the scale of the use of the platform for joint purchases of gas. One problem is the uncertainty about whether the largest gas importers in the EU will be interested in this, which would enable the import of larger quantities of gas at attractive prices. There is no information as to how large the reductions in gas consumption in individual EU member states might be this year, particularly in the winter period, or how to effectively encourage these savings. Despite amending the regulation on the security of supply, it is not fully clear how and by which specific measures to coordinate gas supplies and flows or how to manage them at an interstate level in the event of a possible crisis or the rationing of gas supplies (which would be different from one country to another). Among other things, there is no evidence of advanced works on unblocking the key bottlenecks in the EU gas pipeline network which could enable the smoother distribution of possible alternative supplies and the redirection of gas flows from the West to the East (the European Commission is among those to have called for this).

Finally, and probably most importantly, there is no clear common strategy for reducing the dependence on Russian gas. According to information appearing in the media,[12] the EU’s dependence on Russian gas imports was supposed to fall from last year’s 40% to 26%, but no details were given as to how this is to be achieved. It is known that a few countries have independently decided to stop importing Russian gas (such as Lithuania) or to risk the possibility of Russia stopping their gas supplies (Poland, Bulgaria, Finland, Estonia and Denmark). Some countries – such as Germany – have been making intensive efforts to gradually reduce their dependence, but here too no transparent information has been provided about the size of the decrease in demand for Russian gas in the individual countries. Nor are there any uniform rules of cooperation with Russia in this area.

In addition, the role of the EC in managing this problematic dependency has recently been clearly diminishing and shifting away from it in favour of largely independent, and sometimes even inconsistent, individual actions by individual states. The best illustration of this are the divergent reactions to the “gas-for-roubles” demand, which may significantly hinder solidarity and cooperation in the event of a possible major crisis this winter by deepening the divisions between states and the differences in their competitive situation under conditions of serious gas market challenges and economic problems. Meanwhile, as analyses by research institutions show,[13] despite the high costs of such a scenario, the EU could cope with a total interruption of gas supplies from Russia if there is unity, a large and multi-level coordination of activities (related to obtaining alternative resources, their distribution and burden-sharing), practical solidarity and preparation. In addition to filling up storage facilities and working out contingency plans and the principles of cooperation according to EU guidelines, this could also be manifested in making gas relations with Moscow more coherent. The implementation of joint purchases of Russian gas within the framework of the energy platform could help here, as could the coordination of decisions concerning the pace of transition from Russian imports and the development of specific objectives and incentives.

[1] To reduce gas imports from Russia by two-thirds in the whole of 2022 compared to 2021, the EU would have to give up all Russian gas imports already by the end of May.

[2] For more details, see A. Łoskot-Strachota, ‘Komisja Europejska za wspólnymi zakupami gazu’, OSW, 24 March 2022, osw.waw.pl.

[3] For more details, see M. Kędzierski, ‘An abundance of gas ports. The emergency diversification of gas supplies in Germany’, OSW Commentary, no. 447, 20 May 2022, osw.waw.pl.

[4] For more details, see A. Łoskot-Strachota (cooperation J. Hyndle-Hussein), ‘Wstrzymanie dostaw rosyjskiego gazu do Finlandii’, OSW, 23 May 2022, osw.waw.pl.

[5] L. Lergenmüller, ‘Russland lehnt erstmals Zahlungen aus Deutschland ab’, Der Tagesspiegel, 28 April 2022, tagesspiegel.de.

[6] Gazprom Marketing & Trading is a company from Gazprom Germania Group, which has been under fiduciary management by the German regulator since the beginning of April.

[7] For more details, see S. Kardaś, M. Kędzierski, A. Łoskot-Strachota, ‘Gazowa zimna wojna? Przejęcie przez Niemcy kontroli nad Gazprom Germania GmbH’, OSW, 7 April 2022, osw.waw.pl.

[8] Estimated gas imports from Russia in 2021 by Poland, Bulgaria, Finland, Lithuania, Estonia, the Netherlands and Denmark.

[9] ‘Gas imports. Frequently asked questions – as of 21 April 2022’, European Commission, ec.europa.eu.

[10] ‘EU clarifies how companies can legally pay for Russian gas, ENI and RWE open bank accounts’, Euractiv, 17 May 2022, euractiv.com.

[11] According to Politico, the following have paid or planned to pay under the new scheme: Germany’s Uniper, VNG and RWE, Italy’s ENI, French Engie, Austria’s OMV, Slovakia’s SPP, the Czech Republic’s CEZ, Slovenia’s Geoplin and Hungary’s MVM – see A. Hernandez, ‘Rubles for gas: Who’s paid so far?’, Politico, 25 May 2022, politico.eu.

[12] A. Bounds, S. Fleming, ‘Europe plans for risk that Russia cuts gas supply this year’, Financial Times, 27 May 2022, ft.com.

[13] See e.g. B. McWilliams, G. Sgaravatti, S. Tagliapietra, G. Zachmann, ‘Preparing for the first winter without Russian gas’, Bruegel, 28 February 2022, bruegel.org.