On a new track? The Belt and Road Initiative after the forum in Beijing

The third Belt and Road Forum in Beijing was intended to cast a new light on Xi Jinping’s flagship global initiative. As part of its post-pandemic effort to open up to the world, China has declared that regional projects focused on high-tech and sustainable development, rather than the global infrastructure expansion which had prevailed in previous years, would be the initiative’s driving force. China is also seeking to institutionalise the Belt and Road Initiative and to improve its international reputation by devising internal anti-corruption and pro-environmental mechanisms to operate within its structure. However, similar concepts announced in previous years have failed to significantly alter the operation of this initiative. China’s present actions are a reaction to the mounting debt-related problems faced by developing countries, and to the development of competing initiatives such as the EU’s Global Gateway and the G7’s Build Back Better World.

The Belt and Road Forum itself continues to be an important global diplomatic platform for Beijing. However, this year the number of foreign attendees (23 heads of state and government) was smaller than in previous years. This proves that participation in this format has become much more of a political statement. Russia played a special part in the event, and this year’s edition enabled Vladimir Putin to interact diplomatically with world leaders, mainly those from the Global South, albeit in conditions created and controlled by China. This region is important to Beijing from the point of view of China’s continued economic expansion, as well as in the context of its intention to undermine the US-led global order, in concert with Moscow. However, Beijing has paid a certain price for shaping the Belt and Road Initiative in this manner – this price involves the final annulment of the EU’s participation in it.

A decade of the Belt and Road

On 17–18 October 2023, Beijing’s Great Hall of the People hosted the third Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) Forum. It was held on the occasion of the BRI’s tenth anniversary, after its launch in 2013 in Kazakhstan. The summit was intended to give this cooperation format new momentum after a spell of diplomatic isolation during the COVID-19 pandemic, its economic problems resulting from China’s slowdown,[1] and the increasing rivalry between China and the US. The magnitude of Beijing’s diplomatic challenges is evidenced by the fact that only 23 heads of state and government attended the event, whereas 37 attended in 2019 and 30 in 2017). These mainly included leaders from the Global South, including portions of the ASEAN, Africa, South America and Central Asia. The only high-ranking delegates from Europe were Hungary’s Prime Minister Viktor Orbán and Serbia’s President Aleksandar Vučić. The forum was also attended by Vladimir Putin.

For years, both the Belt and Road Initiative and the forum itself have served as a global diplomatic and propaganda platform which allows Beijing to present itself as a peaceful actor that fosters development. Using this platform, China has also increasingly openly shaped an international environment intended to facilitate the effort to undermine the US-led global order and to create an alternative, China-centric, system of initiatives and institutions. Just like the previous forums, the most recent has served to promote dozens of minor global and regional multilateral projects.

Under the BRI, Beijing has created numerous intergovernmental formats involving public administration bodies, businesses and international organisations, targeted mainly at developing countries. The Belt and Road ‘umbrella’ includes the Beijing Initiative for Deepening Cooperation on Connectivity, the Global Alliance for Innovation in Sustainable Transport, the Beijing Initiative for Belt and Road Green Development, the Partnership for Green Investment and Finance, the Initiative for International Cooperation in Digital Economy and the Global AI Governance Initiative. The regional agenda featured a number of projects targeting Central Asia, Africa and the ASEAN countries, such as the initiative on enhancing cooperation in e-commerce, the regional action plan for developing green technology in Central Asia, and the Belt and Road Green Investment Principles for Africa and the ASEAN. China’s intention to further institutionalise these initiatives has been demonstrated by its decision to establish a Belt and Road Forum secretariat. This body will most likely operate under the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs, which is in line with Beijing’s past practice. However, unlike the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund, these Chinese initiatives do not operate as international organisations with specially established structures, staffs or budgets.

The Belt and Road Initiative is China’s first-ever global project to have forced the West to devise a direct response to it and come up with a counter-proposal. More than a decade of China’s expansion in the finance and construction sectors has brought a new quality to international development funding, including by boosting the importance of hard infrastructure and offering extensive industrial cooperation. However, many of the loans granted under the BRI proved to be economically unviable, some of their terms were confidential, and China was reluctant to co-operate with other lenders in the debt restructuring projects. In some instances, corruption-prone infrastructure and investment projects implemented according to poor standards sparked protests by local residents and exposed China to criticism from the West. This in turn has ‘politicised’ the presence of international partners in this cooperation format. In addition, the G7 states have begun to develop their own competing initiatives such as the EU’s Global Gateway (whose summit was held in Brussels a week after the BRI summit in Beijing) and the US’s Build Back Better World. These cooperation initiatives offer more attractive and sustainable development projects. This has put additional pressure on China to reform its present approach to the Belt and Road Initiative.

Green and sustainable infrastructure

Xi Jinping is the political initiator of this, the first Chinese foreign venture of this scale, and during the forum it was he who presented the new agenda for the BRI. In his eight-point speech, he sought to promote the ideological concepts of “building a common future for humanity” and a “mutually beneficial cooperation” targeted at the Global South. These concepts are intended to highlight the difference between China’s proposals and those offered by the West. However, most importantly, his speech has sent an important signal to Chinese public administration bodies & state-controlled companies; it was intended to give the initiative new impetus, and also to set it on a new track. The infrastructure and investment cooperation which has been promoted over the past decade will continue to play an important part, but its environmental and legal standards will be improved. In fact, Beijing had already announced its initial aspirations in this field at the previous forum back in 2019.

Projects linked with the priorities of China’s domestic development agenda – such as programmes supporting technological innovation, the digitisation of the economy, green energy and transport, as well as the responsible application of artificial intelligence – are expected to act as catalysts for the future development of the BRI. As part of these projects, in its cooperation with the Global South Beijing is presenting itself as an actor which can help others to increase their role in international supply chains, and can support the stance of developing countries in international forums in matters in which they so far have been marginalised. For example, the Initiative for International Cooperation in Digital Economy is expected to foster cooperation between China and Global South countries in developing telecommunications networks and satellite navigation, increasing access to broadband internet, developing e-commerce and advancing the digitisation of the manufacturing industry. China’s Global AI Governance Initiative is intended to boost the role of developing countries in devising the global legal framework regarding AI development.

Beijing is also seeking to give the new version of the Belt and Road Initiative an environmentally friendly aspect. To this end, it has announced that more restrictive environmental standards will apply to the BRI projects, and investments in renewable energy will be carried out on an unprecedented scale. In addition, China intends to include this initiative in the system of anti-corruption mechanisms. During the forum, it also announced its intention to devise international ‘integrity-building’ principles for the BRI, to establish a system to evaluate the transparency of the companies involved in it, and to offer training programmes in cooperation with international organisations. Beijing’s efforts in this regard are a response to the numerous corruption scandals linked with the BRI projects. Back in 2017, it announced its Clean Silk Road initiative, which envisages a plan for its member states to sign bilateral extradition treaties, step up judicial cooperation in criminal investigations, and sign cooperation agreements to combat corruption. Although some of these development proposals regarding the BRI were unveiled at the 2019 forum, ultimately they failed to significantly alter the operation of this cooperation format. The tools for implementing the proposed changes are limited, and mainly depend on the local legislative environment which applies in the country hosting a specific project; corruption in China itself, of course, is also systemic in nature.

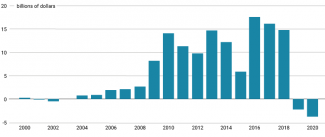

During the October meeting, China announced that it had signed a series of bilateral agreements (mainly letters of intent and initial agreements confirming the intention to sign more specific contracts in the future) with the countries involved in the initiative, worth a total of $97.2 bn. These focus on technology cooperation, the digitisation of the economy and green development. An increase in funding for the China Exim Bank and the China Development Bank of 700 bn yuan (around $96 bn) was announced, and an additional 80 bn yuan (around $11 bn) will be injected into the Silk Road investment fund. The sums pledged, which are smaller than in previous years, reflect the declining scale of China’s financial expansion in developing countries. 2019 saw a drop in Chinese companies’ lending to these countries; this may have been due to a reduction in China’s financial resources as a result of a fall in its trade surplus (regarding goods and services), the exhaustion of some partners’ ability to incur new debt, and to the fact that the income from these loans was smaller than expected. Global economic recession during the COVID-19 pandemic and the rise in US interest rates (Chinese loans were denominated in US dollars) only exacerbated this trend. This have also translated into repayment problems for key recipients of Chinese loans, and consequently, in the need to restructure and roll over the debt owed to China. The share of this type of funding in China’s portfolio has increased from 5% in 2010 to 60% in 2022.[2] It should be expected that Beijing will attempt to significantly increase the quality of the projects implemented, and will use this opportunity to promote yuan-denominated loans while reducing its expenses.

Chart. Net flows (new loans minus repayments) of China’s funding provided to developing countries

Source: C. Reinhart, C. Trebesch, S. Horn, ‘China’s overseas lending and the war in Ukraine’, CEPR, cepr.org.

Rail connections and cooperation in Eurasia

In its present shape the BRI is global in nature, as it engages African, South American, Asian and other countries. The new Silk Road was initiated a decade ago in Kazakhstan, and its first tangible result involved the development of China-EU rail freight. However, over the following years Beijing has expanded it significantly, so that the initiative came to encompass the entire developing world, and its agenda began to include issues other than transport, such as industrial cooperation, digitisation, health and culture. In his speech, Xi Jinping made a reference to the roots of this initiative. In the first part, he announced the creation of a separate China-Europe Railway Forum, and declared that China would join the Middle Corridor which runs from China to Europe via Central Asia and the South Caucasus. On the sidelines of the summit, China signed a letter of intent on this matter (which will be followed by a separate international agreement) with Kazakhstan, and a similar agreement with Iran, which is intended to facilitate the construction of another route running further southwards.[3]

These decisions by representatives of the top echelons of the Chinese Communist Party will likely prompt numerous Chinese cargo carriers to geographically diversify their supply routes. The so-called northern route, which runs via Russia and has been weakened by the destabilisation caused by the Russian invasion of Ukraine,[4] will increasingly be used to handle the dynamically expanding rail freight between China and Russia. In this aspect, the Belt and Road Initiative is becoming an important platform for transforming Russia into China’s raw material base. Beijing has also stepped up its activity in the post-Soviet area as it intends to clear through alternative routes to Europe and Turkey. For example, therefore, it may decide to subsidise the transport operations carried out via the Middle Corridor, which is considerably more costly than the routes which run via Russia, and has recently been affected by insufficient infrastructure capacity.

The new order, Putin and the Global South

The Belt and Road Forum, which is one of China’s most prestigious international events of this type, will continue to serve as a global diplomatic platform for Beijing. Russia plays a special part in it. Putin was the only foreign delegate to address the attendees; he also accompanied Xi Jinping during the opening ceremony and held bilateral talks with representatives of other states.[5] It seems that in this way China intends to signal that Russia will be its main partner in the new global order which Beijing has been shaping through the BRI. The Chinese leadership has also manifested its refusal to isolate Russia in the international arena due to its invasion of Ukraine, and at the same time it has enabled Putin to interact with the world in conditions created and controlled by Beijing. During the summit Xi reiterated his opposition to “ideological confrontation, geopolitical rivalry […] and unilateral sanctions”, thus indirectly offering diplomatic support to Moscow. It is worth noting that in its reports from the summit, the Russian propaganda apparatus emphasised that Putin was not isolated by the international community.[6] However, in the bilateral aspect, Russia has failed to obtain any binding declarations from China as regards the energy sector, which is of key importance to Moscow. This included Russia’s request that China should confirm the launch of work on the Power of Siberia-2 gas pipeline, as this could enable Gazprom to make up for some of the losses it had incurred due to its ban on operating on the European market as a result of the Russian invasion of Ukraine.[7] A major contract for the delivery of 70 mn tonnes of Russian grain to China was also signed during the summit.[8]

The Global South continues to be the main target for the BRI. However, Beijing failed to fill the gap resulting from the absence of European leaders, or to invite more leaders from developing countries. China has been highlighting its historical affiliation with the countries of the Global South and its non-colonial past. This has enabled China to boost its importance in the Global South, together with its infrastructural expansion, and its ability to offer options for funding development which are faster and easier than those offered by the West. The Belt and Road Initiative also fosters cooperation on the reform of global institutions. Despite this, the recent edition of the forum was attended by the smallest number of high-ranking officials in the forum’s history; this was a clear signal to Beijing that participation in the Belt and Road Initiative is not a political priority for many countries. Only five top representatives from Africa came to the event, and half of the ASEAN member states also downgraded their representations. The Middle East was only represented by the United Arab Emirates, although in this region Israel and Jordan are the only countries which have not signed declarations of cooperation with China under the BRI.[9] In addition, despite the fact the 13 Central American and Caribbean countries are formal members of the initiative, none of them was represented by heads of state or government at the forum.

Due to the West’s criticism of the BRI, participation in the summit has become a political statement. This is why some actors have refrained from disclosing their intention to increase their involvement in this cooperation format, out of fear of antagonising the United States. This is because most countries of the Global South do not intend to take sides in the Chinese-American rivalry. These decisions may also have been due to the forum coinciding with the political unrest in the Middle East,[10] the tense domestic situation in some countries, and the 19th Asian Games in Hangzhou (which meant that many Asian leaders had already paid a visit to China at the beginning of October).

The third Belt and Road Forum in Beijing also proved that the initiative no longer serves to enhance cooperation between China and Europe. Apart from Orbán, no EU leaders attended this event, although in previous years they had accounted for around a third of the delegates (10 European leaders attended the forum in 2017, and 11 in 2019). Their absence was due to Putin’s attendance, which had been announced well in advance (delegates from Europe, including from France, left the room in protest after he began his speech). The EU’s top diplomat Josep Borrell ended his visit to Beijing on 14 October to avoid attending the event alongside the Russian president. In addition, a week after the Chinese forum, the European Commission organised a Global Gateway summit in Brussels which was targeted at developing countries. Moreover, during the BRI forum China offered veiled criticism of the West’s actions. On the preceding day, China’s State Council Information Office published its White Paper on the Belt and Road Initiative, in which it indirectly criticised the EU’s policy towards Beijing. It stated its opposition to the concept of de-risking, i.e. the gradual reduction in economic dependency on China, which is being widely promoted in the EU and the US.[11]

Conclusions and outlook

The latest forum, held a decade after the inauguration of the BRI, has demonstrated that the initiative is transforming. At present it is digital issues and green development, rather than rail connections and seaports, which are to play the main part in its activities. This shift has resulted from the fact that a major portion of the project’s planned infrastructure has already been built. Moreover, due to China’s rapid technological development and mounting Western pressure on its high-tech sector, Chinese companies such as Huawei and ZTE have fewer and fewer opportunities to expand onto Western markets. China will continue to use the ‘Digital Belt and Road’ as the main platform for promoting its technology exports, through which Chinese companies will reach the markets in the Global South under the aegis of the BRI.[12] As part of this initiative, Beijing will seek to shape international technology standards, for example by funding the construction of 5G networks in the participant countries and by promoting Chinese technical standards in sectors such as transport and energy. Alongside this, fossil fuels, which have thus far dominated the BRI (in 2013–22 they accounted for two-thirds of Chinese investments in the energy sector in the participant countries), are now to give way to renewable energy. This will create new opportunities for globally competitive Chinese companies operating in the solar & photovoltaic panel, wind technology and electric car sectors.

The Belt and Road Initiative will continue to be a useful political tool in Beijing’s hands, especially in China’s relations with the countries of the Global South. At present its main task is to consolidate the developing countries around China, which is viewed as the final step in China’s efforts to offer them extensive cooperation opportunities (alongside the Global Security Initiative, the Global Development Initiative and the Global Civilisation Initiative). Stepping up cooperation with the Global South, with which Beijing identifies itself historically, is intended to create international legitimacy allowing China to alter the US-centric global order. It also helps China to secure itself access to the emerging markets and critical commodities. On the other hand, the BRI also serves as a platform to foster Russia’s interaction with the world and enables it to reduce its international isolation – on China’s terms. Beijing offers diplomatic support to Moscow, although the latter pays a price for doing so. This involves the ultimate withdrawal of Europe’s involvement in the initiative, as evidenced by the fact that most European leaders have ignored the recent forum.

One new challenge to the Belt and Road Initiative involves emerging global competition posed by projects such as the EU’s Global Gateway and the G7’s Build Back Better World. The West intends these to be attractive alternatives to the BRI; it has launched infrastructure investments in developing countries on their basis, and has maintained strict environmental and labour standards in these projects. Although the scope of these two initiatives is limited, as are the funding opportunities they offer, China’s expansion under the Belt and Road Initiative has provided a genuine impetus to Western development institutions to re-organise according to a new political paradigm. Apart from serving as a tool to develop its relations with the Global South, the European Union’s Global Gateway is intended to diversify the EU economy to make it less dependent on China (the above-mentioned concept of de-risking) by creating alternative supply chains for commodities and components. Although the Chinese Foreign Ministry has called for identifying synergies between the Global Gateway and the BRI, the prospects for cooperation at the global level seem insignificant. However, both projects may develop certain regional synergies.

[1] See M. Kalwasiński, ‘Disappointing post-COVID-19 recovery. China on the path of a protracted slowdown’, OSW Commentary, no. 522, 7 July 2023, osw.waw.pl.

[2] R. Savage, ‘China spent $240 billion bailing out ‘Belt and Road’ countries – study’, Reuters, 28 March 2023, reuters.com.

[3] See J. Jakóbowski, K. Popławski, M. Kaczmarski, The Silk Railroad. The EU-China rail connections: background, actors, interests, OSW, Warsaw 2018, osw.waw.pl.

[4] See J. Jakóbowski, ‘Kolejowy Jedwabny Szlak w cieniu wojny na Ukrainie’, Komentarze OSW, no. 477, 15 December 2022, osw.waw.pl.

[5] See A. Sadecki, F. Rudnik, ‘The Orbán–Putin meeting in Beijing: Hungary drifting away from the West’, OSW, 19 October 2023, osw.waw.pl.

[6] It is unclear why Alyaksandr Lukashenka did not attend the summit. In an attempt to fake reports to prove that he did take part in the Beijing meeting, Belarusian state propaganda used footage from the 2019 BRI Forum which he had attended. This suggests that the absence of the Belarusian leader may have been Moscow’s decision, as Russia is reluctant to demonstrate Lukashenka’s independence in the international arena.

[7] See F. Rudnik, M. Bogusz, ‘The Power of Siberia-2 gas pipeline remains in the design stage’, OSW, 6 April 2023, osw.waw.pl.

[8] See I. Wiśniewska, M. Kalwasiński, ‘Russia seeks access to China’s agricultural market’, OSW, 25 October 2023, osw.waw.pl.

[9] Although the Taliban’s rule of Afghanistan is not internationally recognised, the forum was attended by the Taliban government’s acting minister of commerce and industry Haji Nooruddin Azizi.

[10] See M. Matusiak, ‘Israel attacked’, OSW, 9 October 2023, osw.waw.pl.

[11] See P. Uznańska, M. Kalwasiński, ‘Technologiczny de-risking. Europejska lista technologii krytycznych’, OSW, 9 October 2023, osw.waw.pl.

[12] J. Gunter, ‘Don’t Count on China’s Belt and Road Initiative to Disappear’, The Diplomat, 20 October 2023, thediplomat.com.