Facing another Zeitenwende. How Germany could react to a possible victory for Trump

The news that Donald Trump is almost certain to be the Republican Party’s presumptive presidential nominee has sparked a debate in Germany about the country’s future cooperation with the US. At present, concern about sustaining American military engagement in Europe, including the continuation of aid to Ukraine, is the predominant topic in this debate. However, there are more challenges to come: Germany is also worried that the US will start criticising it again for its trade surpluses and underinvestment in the Bundeswehr.

Trump’s success could trigger another ‘turning point’ in German foreign policy. The German government has no clear plan of action in case it ceases to be the US’s most important European partner if Trump wins. Given the importance of the alliance with Washington and the need to focus more on domestic affairs, Germany will proceed with caution before it makes any pronouncements about a deep revision of its relations with the USA. It is more likely to draw upon its experience from 2017–21: Berlin will avoid any open confrontations, attempt to influence Trump’s inner circle informally, maintain the closest possible cooperation, and uphold the image of Germany as a key partner in Europe within American political, business and academic circles. Trump’s return to power could also lead to the expansion of European potential in the areas of economy, high technology and security. However, at the moment nothing seems to suggest that the German government will take any serious or rapid actions to this effect. These actions will primarily depend on who the next inhabitant of the White House will be.

How Germany feels about Trump: a crisis of confidence

Donald Trump’s presidency marked a significant shift in US-German relations. From the German perspective, his decisions and political approach raised doubts about the stability of the alliance, which is a key pillar of German foreign and security policy. The perception of multilateralism was the main disparity between the Trump administration and Angela Merkel’s government: the US rejected multilateralism as a diplomatic strategy, while Germany continued to view engagement within multilateral frameworks as a fundamental and optimal means of pursuing its interests. The US insistence on bilateralism in foreign policy undermined the effectiveness of the German approach. Trump preferred using military and economic leverage to effectively confront competitors, and Berlin rejected this tactic.[1]

This approach by US diplomacy made it challenging for Germany to foster cooperation with China and Russia, with which it shared economic interests, despite the political threats they pose. Furthermore, the German energy sector was also dependent on Russian supplies. Germany criticised Trump’s perception of international relations primarily in terms of business ties: pursuing American interests became the top priority, even at the expense of antagonising allies. For instance, the imposition of 25% tariffs on steel and aluminium imports into the US in 2018 led to retaliatory tariffs from the EU on certain American imports.[2] US criticism of how Merkel handled migration policy and the eurozone crisis in 2008–9 further undermined Berlin’s trust in Washington. This escalated the negative perception of Trump, who was viewed in Germany as an embodiment of populism and short-sighted politics, while Merkel was depicted as a responsible leader and ‘champion of the free world’.[3]

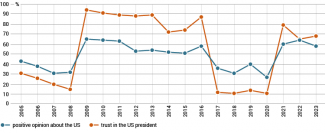

Chart 1. The percentage of Germans who shared a positive opinion about the US and declared trust in the US president between 2005 and 2023

Source: author’s own estimates based on surveys conducted by the Pew Research Center.

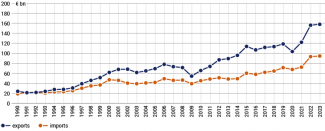

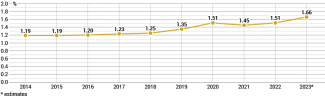

As a result of the changes in the paradigm and style of American foreign policy, expectations and dissatisfaction were expressed more assertively with regard to those countries that, in Trump’s opinion, contributed disproportionately little to their alliance with the US. Germany was criticised most of all; for example, it was accused of maintaining an asymmetry in its trade with the United States. Since 2003 (albeit with some interruptions), Germany’s trade surplus with the US has been growing (see chart 2), reaching a record €63.4 billion in 2023, the highest among all of Germany’s trading partners. One source of this disparity is Germany’s economic policy, which is focused on stimulating exports, while it makes no efforts to strengthen domestic demand. Germany was also criticised for its low defence spending; despite being one of the world’s leading economies, it did not intend to allocate 2% of GDP to defence, as it had committed to during the NATO summit in 2014 (see chart 3). Furthermore, Germany’s heavy reliance on energy imports from Russia, a country which was pursuing an increasingly aggressive policy towards the West, was also seen by Trump as a manifestation of German unfairness.

Chart 2. German–US trade in 1990–2023

Source: author’s own estimates based on data from the Federal Statistical Office.

Germany’s refusal to make any concessions provoked the Trump administration to impose sanctions on the Nord Stream 2 (NS2) gas pipeline in 2019 and to develop a plan to withdraw 12,000 American troops stationed in Germany in 2020, although this plan was halted by the Biden administration. Both these decisions were interpreted in Berlin as ‘punishment’ for failing to conform to US expectations.[4] Germany responded in a similar way to American pressure in the dispute over the involvement of the Chinese companies Huawei and ZTE in the construction of Germany’s 5G network.[5] Despite American warnings that China could use these companies’ infrastructure for espionage and that the US might restrict intelligence cooperation, Berlin refused to change its position for a long time. It was only as a result of cross-party opposition to the Merkel government’s original plans that preparations for excluding Huawei and ZTE from the German telecommunications sector were made in April 2021.[6]

Chart 3. Share of defence spending in Germany’s GDP in 2014–2023

Source: author’s own estimates based on NATO data (as of 14 March 2024).

United in support for Biden and disdain for Trump

Since bilateral relations had become significantly colder, Berlin saw the victory of Joe Biden in 2020 as an opportunity to rebuild its partnership with the US. The new administration expressed willingness to make concessions, as evidenced most strikingly by the decision in July 2021 to refrain from imposing new sanctions on NS2, which made it possible to complete the project.[7] The new coalition government formed by the SPD, the Greens and the FDP planned to expand cooperation with the US covering energy policy, climate, relations with China and other areas.[8] Russia’s subsequent full-scale invasion of Ukraine has not shaken the strategic cooperation between Germany and the United States: despite making mistakes in its policy towards Russia which threatened the stability of the entire EU, Berlin has managed to maintain its role as a key partner for Washington in Europe since 24 February 2022. The US responded positively to the German announcements concerning a thorough revision of its policy, military support for Ukraine and radically increasing its military spending. The Americans appreciated the pace of German efforts to reduce their country’s dependence on gas and oil imports from Russia and replace them with supplies from other sources, including LNG from the United States. As a result, despite all the deficits, Germany remained a priority partner for the Biden administration, which based its policy of supporting Ukraine and deterring Russia on cooperation with its largest European allies. Therefore both the German government coalition and the Christian Democratic opposition believe that Biden’s re-election as president in November would guarantee the continuation of good relations between Berlin and the White House.

The SPD, the Greens, the FDP and the CDU/CSU are all seriously concerned about the highly probable scenario of Trump’s becoming the Republican Party’s presidential nominee and his potential victory. These concerns extend beyond a return to confrontational policies on contentious issues, but also encompass the impact of Trump’s presidency on the American political system. In extreme forecasts, it is feared that he could lean towards authoritarianism and destabilise the cohesion of the West. German commentators and politicians worry that this time around, Trump would rely even more on his own instincts and disregard advice from experts or the party establishment. Instead, he might give more credence to the increasingly influential MAGA (Make America Great Again) movement, which insists among other things on the relocation of a significant portion of American troops from Europe to the Indo-Pacific region and opposes any further expansion of NATO.[9] German politicians’ concerns are echoed by public opinion: according to polls conducted by the Forsa Institute in early January this year, 82% of respondents fear Trump’s return to power, while only 11% are in favour of it.[10]

A tactical plan B: seeking new contacts and cherishing old ones

Over the past few months, politicians from the government coalition have been taking actions to prepare Berlin for Trump’s potential victory. However, these actions do not seem to be part of a coherent strategy. The priority appears to be establishing a network of contacts with the experts and politicians within Trump’s inner circle, and convincing his environment (and his potential voters) of the need to maintain the US’s partnership with Germany. For this reason, German diplomacy is currently seeking good relations with the Republicans: during a visit to the USA in September 2023, foreign minister Annalena Baerbock (of the Greens) met their representatives in the Senate and the governor of Texas among other officials. The interview she gave to Fox News was a gesture towards the Republican electorate. Chancellor Olaf Scholz also made efforts to win the favour of senators on this side of the political spectrum during his recent visit to Washington in February this year.

Germany is also still working to maintain good relations with the Democratic camp, so as to avoid giving the impression that it has accepted Biden’s defeat. This will also allow it to maintain contacts with those congressmen who have influence on US foreign policy, in case the incumbent president loses the election. At the same time, Berlin has launched an informational campaign in the USA targeted at local politicians, representatives of the business and academic communities, and residents of individual states. The narrative it employs is focused on the fact that Germany no longer engages in ‘free-riding’ in the defence sector, as it has taken concrete steps to strengthen its own security, and therefore that of NATO as a whole, by taking steps including the allocation of 2% of its GDP to defence in 2024. Furthermore, Berlin is aiming to be a key European donor of aid to Ukraine, involving itself in stabilising other regional conflicts, and has increased its military presence in the Indo-Pacific region and revised its policy towards China. These actions all demonstrate (according to this narrative) that Germany sees its security interests in the global context, and is ready to support the US in other parts of the world.

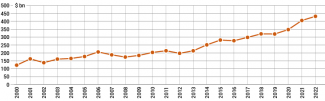

As in 2017–21, Berlin is working to persuade American politicians and entrepreneurs that maintaining good relations with Germany is in their best interests. Hard data supports this claim: in 2022, Germany was the fifth largest investor in the USA ($431.4 billion), and the volume of German investments has been steadily rising in recent years (see chart 4).[11]Both senior government representatives (such as Chancellor Scholz) and lower-ranking officials, including the Coordinator of Transatlantic Cooperation at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Michael Link (FDP), have been involved in promoting this message (see Appendix). The meetings they have been holding provide opportunities to informally promote German interests and expand contact networks within the Republican community at the state level, and to strengthen those which have already been established with the Democrats.

Chart 4. Cumulative German direct investments in the USA in 2000–2022

Source: de.statista.com.

To protect its interests across the Atlantic, Germany has been utilising a network of German diplomatic, trade and cultural agencies, as well as non-governmental organisations co-funded from the federal budget. Currently, this network includes – alongside the embassy, eight consulates general and 39 honorary consuls – over 180 municipal partnerships, five offices of the German Chambers of Commerce Abroad (AHK), two offices of the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD) and six branches of the Goethe Institute. Additionally, branches of the German political parties’ foundations are operating in Washington, D.C. Germany is also leveraging the potential of a broad array of American and German non-governmental organisations which promote transatlantic cooperation (see Appendix).

The volatile strategic responses

Berlin believes that the lack of a strategic plan for potential crises in transatlantic relations is a problem that could be resolved by strengthening the role of the European Union. However, the Scholz government has not presented a clear-cut concept for transforming the EU into an entity which could be capable of shaping global policy on a par with China or the US. Faced with domestic political crises and challenges within the EU, such as in security or agricultural policy, Berlin is more focused on selected issues that could lead to strengthening the EU’s position. Thus far, the most frequently discussed issue has been the reform of EU institutions. On one hand, this focus on reform serves as a way to move forward and respond to criticism that Germany has no vision for the future of the EU. On the other hand, prioritising reforms allows the process of EU enlargement to be decelerated, as it is believed that its institutions need to be prepared for a community with over 30 members.[12]

At the same time, none of the parties which form the government coalition (the SPD, Greens and the FDP) has included a proposal to build autonomous security structures in their respective political agendas for the European Parliament elections. They do anticipate enhancing the integration of military command structures, cooperation within the Permanent Structured Cooperation (PESCO) mechanism, and the expansion and integration of the European defence industry market; but these moves are intended to allow Europeans to respond more independently to threats and thereby strengthen NATO, rather than create an alternative to it. The fact that the Chancellor’s office has firmly rejected any plans to build a European nuclear umbrella as a safeguard in case Trump fails to comply with the US’s commitments as an ally is a clear sign of how strongly European security is linked to the US. At the same time, if a new US president questions the point of the Alliance’s existence or the US’s membership of it, Germany, like the other European NATO members, will face the dilemma of whether and how to develop defence and deterrence in Europe – either within NATO or within the EU’s structures.

It is also unclear how the German government would react to a potential tightening of US protectionist economic policy. Trump has announced that he would put higher tariffs on imports from countries with higher duties than those imposed by the United States. It is possible that EU products would initially be subject to a 10-percent tariff. Some form of retaliation for the European digital tax on tech giants such as Microsoft and Apple may also be expected.[13] Resolving the dilemma of cooperation with China, which is the largest trading partner and a key recipient of German investments, may prove an even greater challenge for Berlin. Trump’s priority is to completely sever economic ties (decoupling) with China, which is seen as the main global rival of the US. A clash between the world’s two largest economies could pose a serious threat to the stability of foreign trade, which in turn would have a major impact on Germany’s economic growth. According to a report by the German Economic Institute (IW), a trade war between Washington and Beijing would lead to a 4.5% decline in German exports, potentially resulting in reduced private investment, or even the relocation of German factories to the US.[14]

Prospects

Germany’s response following a victory for Trump will be contingent on what moves the new American administration takes. A defeat for Biden will not lead to a sudden change in course or even (in an extreme scenario) an open confrontation with Washington. Given the lack of a clear-cut vision for the future of the EU, the weakening of Germany’s role as a European leader after February 2022 and concerns about the escalation of the war in Ukraine, the tactic of ‘waiting out’ Trump which Germany employed during his first term may not work this time. Consequently, in the short and medium term Germany will likely be susceptible to US pressure and ready to yield to some of Washington’s expectations. However, this will foster the escalation of anti-American sentiments, and will be skilfully exploited by such extremist groups as Alternative for Germany (AfD) and the Sahra Wagenknecht-led Movement for Reason and Justice (BSW) to boost their own popularity.

In the long run, the rise of isolationist tendencies in American society may prompt Berlin to ‘Europeanise’ NATO and/or place greater emphasis on strengthening the EU as the only reliable pillar of German foreign and security policy. In this scenario the traditional partnership with France, primarily in the security realm, would become particularly significant, determined by France’s status as Germany’s key ally in Europe, the only EU state with nuclear weapons, and a permanent member of the UN Security Council. The new circumstances could compel Germany to increase defence spending more rapidly, especially since closer cooperation with Paris does not preclude competition with it for leadership in European security, examples of which have already been seen in recent months. Effective strengthening of the EU would also require a more ambitious German policy towards Central Europe, going beyond simply positioning itself as a ‘bridge-builder’ between eastern and western member states. Berlin could be motivated to keep France interested in enhancing relations with the region; this could take the form of Paris seeking allies in central & eastern Europe when dealing with contentious issues with Germany.

APPPENDIX

Support for German and American third-sector organisations and research centres

In 2017–22, the German government offered over €32 million in support for the operation of American and German third-sector organisations & research centres and their projects. These entities can be divided into two groups. The first consists of institutions whose role is to strengthen political, economic and scientific cooperation.[15] In their case, the majority of senior officials, including the Chancellor, almost all ministers and secretaries of state, have participated at least once a year in open debates or closed discussions arranged by them. Events hosted by the Atlantic Bridge (Atlantik-Brücke, AB) based in Berlin and the American Council on Germany (ACG) in New York enjoy particularly high attendance. Both organisations, which have existed since 1952 and are tasked with developing relations between the US and Germany, bring together German and American representatives from politics, media, academic and culture circles. The people who serve as their leaders prove the significance of these organisations.[16] The current chairman of AB is the former SPD leader and Vice-Chancellor Sigmar Gabriel; his predecessor was the current CDU leader Friedrich Merz. Today, its board of directors includes Bundestag deputies, representatives from companies like Google or Ernst & Young, the current German ambassador to Moscow Alexander Graf Lambsdorff, and the former US European Command General Ben Hodges. The ACG is headed by the former US ambassador to Berlin John B. Emerson, who previously served in the administrations of Presidents Bill Clinton and Barack Obama. Representatives of companies such as Warner Bros. Discovery, Pfizer, AT&T and Citibank are among the directors of the ACG.

Germany also utilises American research centres such as the Atlantic Council, the Aspen Institute, the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, the German Marshall Fund of the United States, the Center for Strategic and International Studies, and the Stimson Center to consolidate transatlantic cooperation. Its government has financed these institutions’ projects, which focus on areas such as climate policy, the situation in the Western Balkans and the Indo-Pacific region. German politicians often participate in events organised by American think-tanks and accept invitations from universities in the USA. Some of these entities have branches in Germany, which also facilitates exchanges between German and American politicians and experts. From Berlin’s perspective, continuing cooperation at this level is important, considering the flow of personnel between research centres and the presidential administration. However, these institutions are largely associated with the Democrats. If Trump wins the presidential election, this would help maintain a positive image of Germany within these circles, but would not necessarily facilitate contacts with the new administration. So in the future organisations aligned with the Republicans, such as the Heritage Foundation, may become potential recipients of funds for research programmes.

The second group of entities that can count on government support consists of regional associations and foundations, which are particularly prevalent in the western federal states of Germany; these focus on promoting transatlantic cooperation and disseminating knowledge about the US. The initiatives undertaken by these organisations are primarily aimed at the German public. In the coming years their role may increase, due to the need to curb the potential wave of anti-American sentiment which can be expected if Trump wins.

[1] J. Gotkowska, ‘US-German clash over international order and security. The consequences for NATO’s Eastern flank’, OSW Commentary, no. 294, 22 February 2019, osw.waw.pl.

[2] A. Dimitrova, ‘The State of the Transatlantic Relationship in the Trump Era’, Foundation Robert Schuman, 3 February 2020, robert-schuman.eu.

[3] P. Buras, J. Puglierin, Beyond Merkelism: What Europeans expect of post-election Germany, European Council on Foreign Relations, 14 September 2021, ecfr.eu.

[4] J. Gotkowska, ‘USA – Germany – NATO’s eastern flank. Transformation of the US military presence in Europe’, OSW Commentary, no. 348, 14 August 2020, osw.waw.pl; M. Kędzierski, ‘Niemcy: ostre reakcje na sankcje wobec Nord Streamu 2’, OSW, 23 December 2019, osw.waw.pl.

[5] K. Popławski, ‘Germany is open to Huawei’s participation in 5G’, OSW, 23 October 2019, osw.waw.pl.

[6] L. Gibadło, ‘A dangerous resemblance. Moves to revise Germany’s China policy’, OSW Commentary, no. 473, 19 October 2022, osw.waw.pl.

[7] R. Formuszewicz, A. Łoskot-Strachota, ‘Deal between Germany and the US on Nord Stream 2’, OSW, 22 July 2021, osw.waw.pl.

[8] Mehr Fortschritt wagen – Bündnis für Freiheit, Gerechtigkeit und Nachhaltigkeit. Koalitionsvertrag 2021–2025 zwischen SPD, Bündnis 90/Die Grünen und FDP, 7 December 2021, spd.de, p. 121.

[9] See, for example, C. Stelzenmüller, ‘Flirt mit der Diktatur’, Internationale Politik, 2 January 2024, internationalepolitik.de; R. Pfister, ‘Diktator Trump – ein Szenario’, Der Spiegel, 20 January 2024, spiegel.de.

[10] L. Wolf-Doettinchem, ‘Zweite Amtszeit für Donald Trump? Das denken die Deutschen’, Stern, 9 January 2024, stern.de.

[11] Direct Investment by Country and Industry, 2022, Bureau of Economic Analysis, U.S. Department of Commerce, 20 July 2023, bea.gov.

[12] ‘The EU debate on qualified majority voting in the Common Foreign and Security Policy. Reform and enlargement’, OSW Commentary, no. 545, 12 October 2023, osw.waw.pl.

[13] N. Cook, J. Leonard, ‘Trump Team Targets European Union for Punishing Trade Steps’, Bloomberg, 7 February 2024, bloomberg.com.

[14] J. Matthes, T. Obst, S. Sultan, What if Trump is re-elected? Trade policy implications, IW-Report 14/2024, Institut der deutschen Wirtschaft, Köln, 4 March 2024, iwkoeln.de.

[15] ‘Antwort der Bundesregierung auf die Kleine Anfrage der Abgeordneten Petr Bystron, Tino Chrupalla, Matthias Moosdorf, weiterer Abgeordneter und der Fraktion der AfD. US-amerikanische Stiftungen und Nichtregierungsorganisationen in Deutschland – Teil I.’, Deutscher Bundestag, 26 January 2024, bundestag.de; ‘Antwort der Bundesregierung auf die Kleine Anfrage der Abgeordneten Petr Bystron, Tino Chrupalla, Dr. Alexander Gauland, weiterer Abgeordneter und der Fraktion der AfD. US-amerikanische Stiftungen und Nichtregierungsorganisationen in Deutschland’, Deutscher Bundestag, 10 August 2022, bundestag.de.

[16] M. Klöckner, ‘Atlantik-Brücke: Nicht-legitimierte Privatpersonen nehmen Einfluss auf die Politik Deutschlands und den USA’, NachDenkSeiten, 7 December 2017, nachdenkseiten.de.