A general rehearsal: strategies to contain the AfD

At present, the Alternative for Germany (AfD) is Germany’s second most popular party. In the eastern federal states, it tops the polls with more than 30% of voters’ support, which makes it a ‘catch-all’ or mass party (Volkspartei) which targets all social, professional and age groups with its platform. Its popularity in the east has not waned despite repeated accusations of extremism being levelled at the party and the fact that its members came under counterintelligence surveillance and were accused of acting on behalf of Russia and China.

For the AfD, this year provides a unique test of its popularity. The election to the European Parliament and the three elections to the Landtags of three eastern federal states will serve as a reality check as regards its hopes of jointly ruling these states and increasing its influence on federal-level politics. Strategies and specific campaign solutions are also being put to the test ahead of the federal elections in 2025, in which the party intends to put forward its own candidate for chancellor for the first time.

Should the AfD come to power at the federal state level (this cannot be ruled out), profound changes should be expected, especially as regards migration and energy policies, but also in spheres such as education and history politics. The fear of a victory for the far right is one of the few issues in which the remaining parties stand united. The currently endorsed strategies to contain the AfD are intended to secure the German political system against any attempts to modify it in a profound manner. The Federal Constitutional Court ( BVerfG) and the state media will receive a particular level of protection. All this is happening against the backdrop of the ongoing debate on the possible de-legalisation of the AfD. Another equally important element of the electoral battle against this party involves efforts to by other parties to take on certain particularly popular proposals contained in the AfD’s platform into their own manifestos. These parties are hoping that this could enable them to respond to citizens’ needs and, at the same time, weaken the extremists.

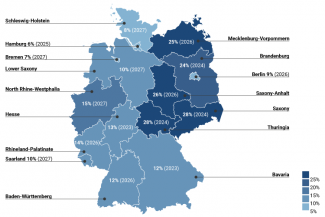

The AfD’s steady rise in popularity is mainly due to German voters’ dissatisfaction with the rule of the present government coalition made up of the SPD, Greens and the FDP. More than 80% of Germans believe that Chancellor Olaf Scholz (SPD) has failed to rise to the challenges facing Germany, including the new phase of the migration crisis, the cost of the climate policy and the scale of the aid provided to Ukraine, which some respondents believe is excessive (especially those in the eastern federal states). In each of these aspects, the AfD has proposed policies which are radically different than those pursued by the government, and this has attracted disillusioned voters. However, the party’s electorate in eastern Germany is not limited to individuals who are disappointed with the post-1989 transformation and the still present differences between the eastern and western parts of the country.[1] Representatives of all social groups from both sides of Germany’s former internal border are increasingly willing to vote for the AfD. In recent elections, the party was successful iin affluent western federal states such as Bavaria and Hesse, where it came second and third respectively, thus becoming the main opposition force there.[2]

Map. Level of support for the AfD in specific federal states (the date of the next election is provided in brackets)

Source: author’s own analysis based on wahlrecht.de.

Voters frequently cite their support for selected issues from the AfD’s platform regarding spheres such as migration policy, security, the economy or social issues as their motivation for voting for this party (see Appendix).[3] Another important motivation involves the conviction shared by 55% of those surveyed that the far right formulates correct diagnoses of Germany’s problems.[4] Many voters view the AfD as an alternative (in terms of the political platform) to the ruling coalition and the main opposition force, that is the Christian Democrats. 45% of respondents believe that if the CDU/CSU came to power, they would not be capable of modifying the manner in which Germany is governed.[5] The AfD is also supported by numerous young voters, topping the polls conducted for this group of the electorate. Moreover, its level of support among young Germans has increased from 9% in 2022 to the present 22%.[6]

The professionalisation of the party’s activities, in particular its skilful use of social media, has significantly boosted the AfD’s popularity. TikTok has become the key tool in the party’s online strategy. As a consequence, in January 2024 the number of followers on its TikTok account reached 3.6 mn. This is more than the total number of followers recorded by the remaining parties taken together, which is 1.2 mn. The most popular video posted on TikTok by Maximilian Krah (the AfD's main candidate in the European Parliament elections) has had more than 1.4 mn views.[7]

Gasping for breath

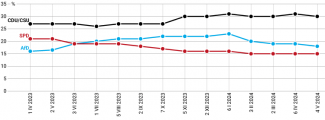

The decline in support for the AfD, which has been evident in the federal-level polls since the beginning of the year, may hamper the party’s success in the state-level elections. This decline is due to two main factors. The most important one involves the emergence of the competing Sahra Wagenknecht Alliance (BSW) in January this year. The former deputy chairperson of the Die Linke party has targeted a similar electorate, that is individuals who are critical of a liberal migration policy and a radical climate policy. Her electoral slogans include anti-American views and opposition to helping Ukraine.[8] The main difference between the AfD and the the BSW involves the absence of allegations of historical revisionism and right-wing extremism against Wagenknecht and her supporters. Moreover, in the eastern federal states, where the BSW’s level of support is relatively high, the fact that voters have a friendly attitude towards the alliance’s leader herself is important. Wagenknecht, who was born in Jena (Thuringia), highlights her East German identity, although she permanently resides in Saarland (near the border with France) and has pursued her political career in Berlin and North Rhine-Westphalia.[9]

Chart 1. Level of support for the CDU/CSU, the AfD and the SPD between April 2023 and May 2024

Source: author’s own analysis based on dawum.de.

Another factor undermining the AfD’s level of support nationwide involves large demonstrations attended by several thousand protestors,. These were held in late January and early February this year. They were attended by Chancellor Scholz, and in a video message Germany’s President Frank-Walter Steinmeier emphasised that the demonstrators were “defending our republic and our constitution against enemies. They are defending our humanity”. There was a wave of public outrage in response to reports published by the investigative journalism organisation Correctiv about a secret meeting of far-right extremists convening various parties in November 2023 in a villa near Potsdam. This was chaired by Martin Sellner, an Austrian national and one of the radical groups’ leaders. He presented a phased plan to carry out the ‘re-migration’ or expulsion of several million individuals from Germany, both refugees/immigrants and German citizens who support a liberal migration policy. The meeting was attended by several AfD politicians including a close aide to the party’s co-leader.

The decline in the AfD’s level of support was also due to further reports regarding the actions carried out by the party’s top politicians and their aides which benefitted Russia or China. These individuals included Krah (and his assistant) and Petr Bystron, the leaders of the list of the AfD’s candidates for the European Parliament elections. This resulted in the exclusion of AfD MEPs from the Identity and Democracy (ID) group at the parliament and the cessation of their cooperation with Marine Le Pen’s party.[10] So far, the lower level of support recorded in nationwide polls has not translated into any major decline in the party’s approval rating in the eastern federal states. Similarly, profound internal disputes over the party’s platform and certain personal issues, which have been put to one side for the duration of the campaign, have not undermined the party’s popularity. Moreover, the number of AfD supporters continues to be high despite repeated leadership crises, chairmanship reshuffles, scandals over improper party funding, as well as differences within the eastern and western party structures (the latter ones are usually more moderate).[11]

A fragile cordon sanitaire

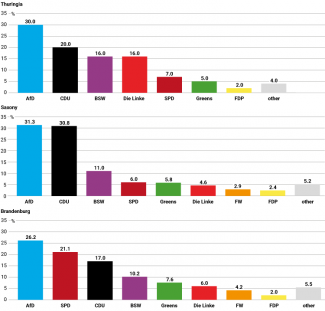

Heated debates have been ongoing in Germany regarding the consequences of bpossible consecutive victories for the AfD. Its successes in Thuringia, Saxony and Brandenburg came as a shock to Germany’s citizens and have become a test for the state’s political system. According to a likely scenario, only three or four parties will make it to the Landtag (especially in Saxony and Thuringia): the AfD, the CDU, Die Linke (in Thuringia) and the BSW. It is likely that the SPD, the Greens and the FDP will fail to cross the electoral threshold (which is 5%). Such a result will make it difficult to build a coalition, and this, in turn, could help the AfD to take power.

Chart 2. Support for political parties in Thuringia, Saxony and Brandenburg

Source: author’s own analysis based on dawum.de.

In recent years, political alliances made in the eastern federal states were based on the principle of a ‘cordon sanitaire’ (Brandmauer) intended to prevent the AfD from coming to power. This practice resulted in bizarre and unusual coalitions being formed such as those between the Christian Democrats and the Greens, the FDP or the SPD, and in Thuringia it saw the CDU effectively supporting the minority government formed by Die Linke, the SPD and the Greens. In particular for the Christian Democrats this has provoked a dilemma regarding their potential cooperation with Die Linke and the BSW, which are their biggest political opponents (aside from the AfD). Moreover, since 2018 the CDU has clearly ruled out formal cooperation with both the AfD and Die Linke in its documents. Effectively, however, this rule is increasingly difficult to follow, especially at the local government level, where the Christian Democrats sometimes support the proposals put forward by the AfD and vote for them.[12] Ultimately, it may turn out that the outcome of the election in Thuringia will result in either cooperation between the CDU, Die Linke and the BSW or a coalition between the AfD and the BSW, and in Saxony the possible options will involve cooperation between the AfD and the BSW or between the CDU and the BSW, or an AfD-only government.

An alternative reality

Even without an independent majority, in some federal states the AfD may be able to form a minority government which will seek temporary support from other parties. If this happens, the party could take over control of several highly important ministries, such as the state ministry of internal affairs, which is responsible for the police and counter-intelligence structures, as well as for migration policy, including the support offered to Ukrainian refugees and decisions regarding deportation. It could also acquire a major influence on energy and education policies, as in these two spheres the federal states have autonomy.

The AfD coming to power would most strongly affect Germany’s historical policy because it is this party which has challenged the basic assumptions of this policy, for example by referring to the Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe, which is located in Berlin’s city centre, as a ‘monument of shame’[13] (it should be noted that this ‘shame’ refers to the decision to put the memorial in the centre of the German capital). The AfD’s potential actions could include a revision of the funding of places of remembrance (this former German concentration camp Buchenwald is located in Thuringia) and attempts to put pressure on the education bodies to modify the content of school textbooks. A victory in the federal state election would also enable this party to appoint numerous public officials, such as the president of the Landtag, who manages the practical operation of the parliament, and to staff some public administration posts, supervise the flow of information and the legislative process. The COVID-19 pandemic demonstrated the extent of the competences of the governments of individual federal states. This was when most decisions which greatly limited the civil liberties were formally made at the federal state level.[14]

One of the important competences of each federal state’s minister-president involves the right to terminate various agreements, including those relating to the state media. Germany’s media system relies on a federal structure which is composed of central media organisations such as ARD and ZDF, and nine regional broadcasting companies which are responsible for broadcasting content which is adjusted to the characteristics of each specific region of Germany. These organisations are supervised by the broadcasters’ boards (Rundfunkrat) which include a total of more than 500 individuals representing various social groups. Their task involves approving individual broadcasts and appointing the directors of specific media organisations. If Thuringia terminated its agreements with the remaining federal states (the so called Medienstaatsvertrag agreements), which is what the AfD proposed back in 2022, then one of the results of this would be financial problems for TV and radio stations, layoffs of journalists and reporters, and the need to launch negotiations with the remaining federal states regarding a new cooperation agreement.[15]

Alongside this, the party’s influence on federal-level politics would be limited, even in the event it forms a government in one of the federal states. The separation of powers in Germany which has been in place for 75 years and which encompasses numerous forms of consultation and decision-making is based on a compromise between the federation and the federal states, and this safeguards the country against rapid change. Due to the ‘fuses’ which were built into the German political system after the Second World War, any party attempting to gain a fundamental influence on federal-level policy making, would first need to seize power in at least nine of the 16 federal states and to obtain a majority in the Bundestag. Only then could it implement profound modifications to the German legal and media landscape. However, this does not mean that the AfD’s growth potential should be downplayed. Its successful attempts to gain a new foothold in the power structures in the federal states may enable it to block some of the laws which require the Bundesrat’s approval within a few years. To achieve this, it would need 35 votes in the 69-seat Bundesrat (each federal state is represented there in proportion to its population). In addition, the AfD gaining more than a third of the seats in the Bundestag could result in it blocking constitutional amendments or paralysing the election of BVerfG justices.

Adding the finishing touches to the system

The response to the possibility of the AfD coming to power from the remaining parties has been to seek to strengthen the institutions of the state and to close the loopholes which facilitate the circumvention of the rules currently in place. The BVerfG alongside its counterparts in the individual federal states is the key body in this constellation. The rulings which these courts pass ultimately determine the legality of actions taken by politicians, provided that they are respected. The current rules on the election and tenure of BVerfG[16] justices, which are regulated in specific legislative acts rather than in the federal constitution, are the Achilles’ heel of this system. This is why a heated debate has been ongoing in the Bundestag on amending the Basic Law. The purpose of such an amendment would be to enshrine in the constitution a 12-year term of office for justices who would be elected by votes casts by a two-thirds majority of the members of the Bundestag, with no possibility of re-election. Considering the declarations by the ruling coalition and the main opposition parliamentary group, that is the CDU/CSU, it can be assumed that the constitution will be thus amended by the end of the present term.

Individual federal states are considering similar steps.[17] The main proposals regarding the intention to curb the AfD’s activity include modifications to the rules of how the Landtags operate. This could for example result in the implementation of stricter rules for the appointment of candidates for some posts (including the president), in increased transparency of the process of electing the minister-president of each federal state, including, for example, through open voting, and a reduction in the number of so-called political officials (including the head of the local counter-espionage structures, the head of the Landtag chancellery and the chief of the state police, who are subject to a reshuffle following each federal state election). Another very important element is the attempts to rule out the possibility of holding ‘consultation plebiscites’ and using them to put pressure on politicians to initiate a legislative process regarding a specific issue. The AfD views this as one of the most important political tools; this was clear when it proposed to amend the federal constitution to introduce a system of referendums.[18] As regards modifications to the education system, these could be prevented to some degree by amending the legal basis for the operation of state-level civic education centres (LpB).[19] At present, this legal basis often includes (for example in Thuringia) government orders rather than laws, which makes it significantly easier to amend. In addition, raising the official status of the LpB could boost this institution’s independence and its financial basis. This has already been done in Bavaria, where the LpB is now considered a public law institutions (AöR).

There has been an increase in attempts to curb the activity and influence of the AfD in both Berlin and across Germany. These include initiatives endorsed by Federal Interior Minister Nancy Faeser (SPD) to provide financial support to organisations which promote democracy and to organise civic education in schools. The German interior ministry also intends to toughen the legislation regarding the operation of social media, which the extremists, including some AfD activists, use as their mobilisation platform.[20] Finally, steps have been launched to restrict access to classified information for AfD politicians in order to exclude them from committees responsible for the operation of the secret services.[21]

This ostracism towards the AfD is not without precedent. Since 2017, when the party made it to the Bundestag for the first time in history, the remaining parties have consistently denied it the opportunity to chair the parliamentary sessions. In repeated votes for the position of vice president of the Bundestag none of the AfD’s candidates has won sufficient support. Moreover, the Bundestag distributed its funds for political foundations, which receive a total of around €700 mn annually (this sum exceeds the federal budget subsidy for political parties), in such a way that the Desiderius-Erasmus-Stiftung, an organisation linked with the AfD and headed by Erika Steinbach, received no funding. The party challenged this decision and the BVerfG agreed with it, stating that the hitherto applied informal rules for the distribution of funds were unconstitutional. According to new rules, which were adopted last November, political foundations are required to promote democracy and the ministry of the interior decides whether this requirement has been met. This de facto continues to prevent the AfD from obtaining funding.[22]

Should it be banned or not?

The most important debate regarding the AfD is linked with the question regarding whether this party’s activity should be de-legalised. Most Germans do not support this plan (51%) and argue that the remaining parties should modify their policies (65%) and solve the problems which the AfD is highlighting. 37% of the respondents are in favour of launching the de-legalisation procedure.[23] They emphasise the price of inactivity and the need for society to react to the anti-democratic statements spread by the AfD leaders. They also argue that the office for counter-intelligence should monitor the party and its youth organisation (Junge Alternative für Deutschland) and that manifestations of anti-Semitism in the party ranks should be condemned. In addition, they emphasise the need to send a warning sign to other parties which could intend to challenge democratic institutions in a similar manner. However, since the criteria which form the basis of how a ban on political activity could be introduced are tough, in the history of contemporary Germany there were only two instances (in the 1950s) in which this procedure was successfully completed.

Critics argue that the de-legalisation procedure is lengthy and will not affect the coming elections, neither the elections in the eastern federal states nor next year’s Bundestag elections. Moreover, they fear that, if this procedure is initiated, this could mobilise those voters who would view the AfD as a victim of collusion by the remaining parties, and this would be counterproductive. The AfD’s potential de-legalisation could also encourage its members to operate outside the public sphere and make it more difficult for counter-intelligence to infiltrate the organisation. German constitutionalists emphasise that, in order to ban a party, it is necessary not only to demonstrate its anti-democratic nature, but also to convince the BVerfG that the organisation has the genuine potential to implement its plans. Recent years have seen two unsuccessful efforts to de-legalise the NPD, which is an openly Nazi party. The first attempt failed due to the presence of secret counter-intelligence collaborators within the party structures. In the second attempt, the BVerfG considered the NPD to be a party of marginal importance and unable to implement its platform. The decision to initiate a de-legalisation procedure can only be made by the Bundestag, the Bundesrat or the Federal Government. However, the politicians are divided across party lines in their approach to the ban.

Restricting a party’s access to public funds is easier than de-legalising it. State funding can be withdrawn even when the party does not meet the criterion regarding its potential for achieving anti-constitutional goals. In January this year, the BVerfG approved a joint request submitted by the Bundestag, the Bundesrat and the Federal Government to exclude the NPD and its possible successor organisations from party funding for a period of six years (the longest possible period envisaged by the law). The party is exempt from tax relief during this period. According to some politicians, the application of this solution to the AfD could help to curb its activity.

AfD politicians could also be stripped of some civil rights in the event of them abusing these to challenge the constitutional order. The Bundestag, the Federal Government and the state government are authorised to submit a relevant request. So far, the BVerfG has rejected four of these requests. Initiators of the most recent campaign entitled ‘Resilient democracy: let’s stop Höcke’, which is intended to strip Björn Höcke, the AfD’s leader in Thuringia, of his passive voting rights, managed to collect almost 2 million signatures, which made it possible to refer the matter to the Bundestag.[24] The ruling coalition’s parliamentary groups will now decide whether to pass it on to the BVerfG. In 2019, a court ruled that Höcke can be called a ‘fascist’. He may be the first AfD politician to become the minister-president of Thuringia as a result of the autumn election.

Outlook

It seems unlikely that a procedure to de-legalise the AfD could be initiated soon. Even if this happens, the problem of the party’s supporters will need to be solved, as they will need a new political group they could join. Some of the AfD’s voters would most likely seek out other extreme groups to express their opposition to government policies. Some could support other initiatives operating outside the political system, which could lead to an increase in social radicalism and prevent the law enforcement bodies from monitoring their activity. In the context of this year's elections in the eastern federal states, the most likely scenario is that legislation will be amended to reduce the potential for bending the law. This is intended to prevent the AfD from implementing profound political change, even in the event of an electoral victory.

Fear of the AfD is one of the few factors which unite both the internally divided coalition parties, and also the government with the Christian Democratic opposition. Most politicians agree that the most important method for preventing this party from succeeding involves revising their own policies. In the context of the upcoming elections, it should be expected that the individual parties will compete in presenting their platform proposals resembling the AfD’s statements (albeit in a watered-down form). If this strategy proves successful, it will likely be repeated ahead of the elections to the Bundestag planned for autumn 2025.

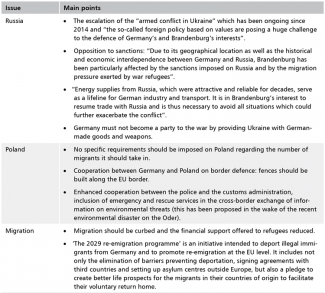

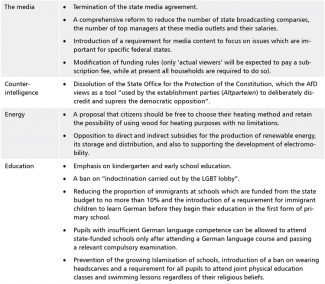

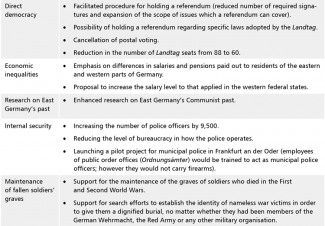

APPENDIX

The AfD’s electoral platform in Brandenburg

So far, a document pertaining to Brandenburg alone has been published. The AfD entitled it a ‘Government platform’ (Regierungsprogramm). Numerous proposals contained in the AfD’s platform compiled for individual federal states make a reference to federal- or EU-level politics and are not subject to regional-level policies. This includes the possible decisions to withdraw from the Paris Agreement on climate change and to toughen the rules for granting German citizenship. AfD politicians have endorsed these two issues

[1] ‘Dlaczego Niemcy coraz częściej popierają radykalną AfD? Alternatywa dla Niemiec rośnie w siłę’, OSW, 4 July 2023, youtube.com.

[2] K. Frymark, ‘Victory for the Christian Democrats and success for the AfD in Hesse and Bavaria’, OSW, 10 October 2023, osw.waw.pl.

[3] For more on the AfD’s platform see K. Frymark, ‘Too green, too fast, too dear. The AfD is gaining popularity in Germany’, OSW Commentary, no. 518, 20 June 2023; ‘AfD – postulaty, geneza, podejście do Polski, szanse na dojście do władzy’, OSW, 14 May 2021, osw.waw.pl.

[4] ‘ARD-DeutschlandTREND Juli 2023’, Infratest dimap, 5 July 2023, infratest-dimap.de.

[5] ‘Mehrheit: Regierung hält – trotz Streit’, ZDF-Politbarometer, 26 April 2024, zdf.de.

[6] S. Schnetzer, ‘Neue Trendstudie „Jugend in Deutschland 2024“: Verantwortung für die Zukunft? Ja, aber’, 23 April 2024, simon-schnetzer.com.

[7] M. Brodkorb, ‘Die AfD spielt Hase und Igel’, Cicero, 26 April 2024, cicero.de.

[8] K. Frymark, ‘Germany: the launch of the pro-Russian Wagenknecht party’, OSW, 29 January 2024, osw.waw.pl.

[9] Idem, ‘Alternatywa dla wschodnich Niemiec. Saksonia i Brandenburgia przed wyborami landowymi’, Komentarze OSW, no. 307, 28 August 2019, osw.waw.pl.

[10] Idem, ‘Chinese and Russian spies in the crosshairs of Germany’s secret services’, OSW, 23 April 2024, osw.waw.pl. Krah has also been accused of relativising German crimes perpetrated during the Second World War.

[11] Idem, ‘Niemcy: walka frakcyjna na zjeździe AfD’, OSW, 3 December 2020; ‘Nowe władze AfD: w kierunku regionalnej partii protestu’, OSW, 27 June 2022, osw.waw.pl.

[12] S. Hummel, A. Taschke, ‘Hält die Brandmauer? Studie zu Kooperationen mit der extremen Rechten in ostdeutschen Kommunen’, Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung, December 2023, rosalux.de; ‘Beispiele kommunaler Zusammenarbeit zwischen CDU und AfD’, Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung, September 2023, kommunalwiki.boell.de.

[13] B. Rudawski, ‘Alternatywa dla Niemiec a niemiecka historia. Nowy początek w polityce historycznej?’, Biuletyn Instytutu Zachodniego, no. 349/2018, iz.poznan.pl; M. Linden, ‘Des Teufels Generäle – Der Geschichtsrevisionismus der AfD liegt offen auf dem Tisch’, Neue Zürcher Zeitung, 25 November 2019, nzz.ch.

[14] A. Kwiatkowska, ‘Federalizm na cenzurowanym. Współpraca i konkurencja między landami w dobie pandemii’, Komentarze OSW, no. 343, 10 July 2020, osw.waw.pl.

[15] In November 2022 the AfD submitted a request to the Landtag of Thuringia to terminate the agreement. See Antrag der Fraktion der AfD: ‘Grundlegende Reformen des öffentlich-rechtlichen Rundfunks ermöglichen, Staatsverträge kündigen, Rundfunkbeitrag abschaffen’, Thüringer Landtag, Drucksache 7/6697, 15 November 2022, parldok.thueringer-landtag.de.

[16] Articles 93 and 94 of the German Basic Law mainly regulate the competence of the BVerfG’s jurisdiction and the body’s line-up; they define the method for appointing BVerfG justices: half the members are elected by the Bundestag and half by the Bundesrat. BVerfG justices may not be members of the Bundestag, the Bundesrat, the Federal Government or any of the corresponding bodies of a federal state.

[17] H. Beck, J. Jaschinski, K. Kordt, M. Müller-Elmau, J. Talg, Rechtsstaatliche Resilienz in Thüringen stärken. Handlungsempfehlungen aus der Szenarioanalyse des Thüringen-Projekts, Verfassungsblog, Berlin, April 2024, verfassungsblog.de.

[18] ‘Entwurf eines Gesetzes zur Einfügung von Elementen direkter Demokratie in das Grundgesetz’, Deutscher Bundestag, Drucksache 20/6274, 31 March 2023, dserver.bundestag.de.

[19] The Federal Agency for Civic Education (Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung, BpB) was established in Bonn in 1952. It was rooted in the re-education policy carried out by the Allies in West Germany post-1945. It purpose was to re-educate Germans to embrace democracy, political pluralism and human rights. The BpB is supervised by the interior ministry and its operation is subject to an assessment carried out by a special body composed of 22 members of the Bundestag. Its annual budget is around €74 mn; in addition, regional branches of the BpB, known as LpB, are operating in individual federal states. The organisation is involved in organising conferences, seminars, study visits etc. It also publishes materials linked with important political and social issues.

[20] ‘Rechtsextremismus entschlossen bekämpfen. Instrumente der wehrhaften Demokratie nutzen’, Bundesministerium des Innern und für Heimat, February 2024, bmi.bund.de.

[21] O. Maksan, ‘Deutsche Geheimdienste: AfD und Linkspartei fliegen aus Kontrollgremium’, Neue Zürcher Zeitung, 25 March 2022, nzz.ch.

[22] K. Frymark, ‘Germany: Law on the financing of party foundations’, OSW, 15 November 2023, osw.waw.pl.

[23] E. Ehni, ‘Knappe Mehrheit gegen AfD-Verbotsverfahren’, Westdeutschen Rundfunk, 1 February 2024, tagesschau.de.

[24] S. Locke, ‘Mehr als 1,6 Millionen Menschen wollen Björn Höcke die Grundrechte entziehen’, Frankfurter Allgemeine, 1 February 2024, faz.net.