A country of interim governments. The political crisis in Bulgaria and the attempts to solve it

Bulgaria has held five parliamentary elections over the past three years. On 9 June, the citizens of this country will once again elect a new parliament in yet another snap election. A series of interim cabinets appointed by President Rumen Radev, without the parliament being involved, have governed for a significant part of this time as it has been impossible to form a working government based on a parliamentary majority. The experiment of the so-called rotating government, created after the 2023 elections by the two largest parliamentary forces, the centre-right GERB and the centrist-liberal We Continue the Change–Democratic Bulgaria (PP-DB), also proved unsuccessful.

The governments formed by a parliamentary majority have made attempts to repair the state, which was interspersed with efforts to maintain the political and oligarchic status quo, as this benefits a section of the political and bureaucratic-business class. The prolonged political crisis has negatively impacts the country’s international standing, and the inability to reach a lasting compromise between the parties in the National Assembly is hindering the attainment of ambitious political goals, such as adopting the euro or fully joining the Schengen area, as well as addressing domestic issues such as systemic corruption and the highest poverty level in the EU.

The origins of the crisis and the ‘parliamentary interregnum’

Although Bulgaria is a parliamentary republic, due to the permanent inability to form a government with a stable majority, it has in fact come to function as a de facto presidential system over recent years. The president has played an extremely important role during this prolonged crisis as he has remained the main player on the political stage following the collapses of successive governments based on fragile parliamentary majorities, and he has been busy assigning roles to various actors. Normally the government is formed by the 240-member National Assembly, elected for a four-year term based on proportional representation. Under ordinary constitutional conditions, the president primarily performs a representative function.

However, if there are difficulties forming a government or a parliament is dissolved, the president’s role becomes crucial – something Radev has exploited for many years. Alongside the decision to dissolve the National Assembly, he is obligated to appoint an interim cabinet to govern until a new majority forms after elections. Until the constitutional reform implemented in December 2023, the selection of the interim government’s members, including the prime minister, was the exclusive prerogative of the president and did not need to be consulted with any other power centre. Consequently, these interim governments included individuals who were politically close to the head of state. The intention of the constitutional reform enacted last December was to curb the president’s dominance in situations of unstable governments. The president used the interim cabinets to control the executive branch, which in turn implemented the political goals he had set. In addition to this, President Radev, who has been in office since 2017 and is currently in his second term, has used the periods of ‘parliamentary interregnum’ and interim governments as an opportunity for reshuffling personnel in the most important institutions and state-owned companies without the need to consult the National Assembly. For example, in August 2022, a few days after the resignation of Kiril Petkov’s government and the dissolution of parliament, the president fired the top managers and the board of directors of the national gas company Bulgargaz to replace them with his close associates, and dismissed all 28 regional governors who had been appointed by the previous cabinet.

The Bulgarian constitution has no precise provisions that set a maximum deadline by which a new government should be appointed, and this additionally complicates the formation of a stable majority after parliamentary elections. As a result, negotiations between potential coalition partners are prolonged, sometimes lasting for months; such a state of affairs offers the president the opportunity to indirectly exercise full executive power through an interim government. One example of this was the situation following the collapse of Petkov’s cabinet and the dissolution of parliament in August 2022. From that time, two interim governments led by Galab Donev remained in power for 10 months, as the early elections for the National Assembly in October 2022 did not result in the formation of a cabinet based on a parliamentary majority.

What also makes it easier for the president to play a greater role during government crises are the peculiar provisions of the constitution regarding the deadlines for forming new cabinets. The constitution does not specify the time within which a new government must be appointed after elections, but at the same time, it provides an extremely short period of seven days for the prime minister-designate to form a cabinet[1].

Since the constitution fails to define a deadline by which the president must nominate a prime minister, the president can extend the period during which interim governments remain in power. This situation occurred after the snap elections in October 2022. Radev argued that there was no need to rush in forming a new parliamentary majority, as the interim government was managing the key sectors effectively. The president decided relatively quickly to task politicians nominated by the two largest parliamentary groups with forming a government, but he delayed assigning this task to the third candidate (the constitution allows for three attempts to form a government by parliamentary groups) until mid-January 2023. This move was intended to both extend the interim governments’ tenure and delay new elections until early spring 2023.

The constitutional amendments enacted during the government of Nikolai Denkov (June 2023 – March 2024), which were supported by GERB, the PP-DB and the Movement for Rights and Freedoms (DPS) representing the Turkish minority, curtailed some of the presidential powers in this regard[2]. The head of state can now only choose an interim prime minister from a narrow group of a few senior state officials, including the president and vice president of the National Bank of Bulgaria, the ombudsman and deputy ombudsman, and the president of the National Audit Office. Furthermore, the amended constitution now states that a dissolved parliament continues to function until the new tenure of the National Assembly is constituted (previously, once a parliament was dissolved the deputies automatically lost their mandates, and the National Assembly could not convene).

This reform thus effectively deprived the president of the instruments that had previously enabled him to take many key decisions during parliamentary interregnums without the executive branch being involved. Nevertheless, amending the constitution – which in many countries is considered an ambitious political goal and proof of the political class’s ability to reach long-term compromises – did not provide a sufficiently strong common ground for the parliamentary majority to survive under Bulgarian conditions. Denkov’s government was expected to be one of the two rotating cabinets formed by GERB and the PP-DB after the 2023 elections, but it did not continue. This proves that limiting the president’s position, which is objectively a very important move for the country’s political system, was not in itself enough to resolve the crisis. Another element that is equally important in overcoming such a crisis should be the political class’s ability to reach consensus, but this is clearly missing from Bulgaria’s political life.

Political sources of instability

Another source of the weakness of Bulgarian parliamentary democracy, in addition to the institutional factors, is the specific nature of the party landscape which has been slowly forming since the beginning of the political transformation. Since the 1990s, it has largely been based on the creation of new political parties as groups serving the interests of oligarchic elites. The emerging civil society has had relatively little involvement in this process, as for a long time it has been a passive observer rather than an active participant in political processes.

During the first decade of parliamentary democracy, there was a relative balance on the Bulgarian political scene between the two strongest political camps: the post-communist left, centred around the Bulgarian Socialist Party (BSP), and the centre-right, represented by the Union of Democratic Forces (SDS). Later, this balance gradually gave way to pluralisation as new political parties emerged, including the National Movement for Stability and Progress (NDSV), led by the last Tsar of Bulgaria, Simeon II. One effect of these processes was the development of a new generational formula for the Bulgarian centre-right, namely the emergence of the GERB party, which has been led since 2006 by Boyko Borisov, a former mayor of Sofia.

Boyko Borisov’s party remained in power for over a decade. Between 2009 and 2021, GERB won five consecutive elections, governing the country for 12 years with few interruptions. This period was marked by the perpetuation of an elite-oligarchic model, pervasive corruption, an ineffective justice system and increasing political instability. Under Borisov’s rule, Bulgaria was affected by recurring social crises related to problems stemming from the global financial crisis that had begun in 2008. The recurring public discontent was driven by the low standard of living for Bulgarians compared to other EU residents, as well as periodic rises in prices and living costs, in particular, energy prices[3].

One element of Borisov and GERB’s strategy during their long tenure was to temporarily overcome political and social crises by dissolving the cabinet several times, making it necessary to schedule snap elections. Temporarily handing over power to presidential cabinets was a price Borisov was willing to pay to return to power after the elections. The GERB leader continued to use this tactic even after Radev, who originated from the BSP and had an openly negative attitude towards GERB and Borisov himself, assumed the presidency. This modus operandi was employed particularly during periods of intense public protests. It was not until 2021 that Borisov’s ‘forward escape’ tactic failed, and GERB lost power for two years as a result of three snap elections.

Hopes for change

Following the wave of public protests in 2020 and the April 2021 elections, it seemed that the Bulgarian political sceneas shaped in the 2000s was on the verge of breaking apart. New political formations emerged, such as the party There Is Such a People (ITN), led by the musician and celebrity Slavi Trifonov, which resembled other anti-establishment protest parties popular across Europe, and the movement We Continue the Change (PP), led by Kiril Petkov and comprised of Western-educated people in their forties who aimed for an ambitious reform agenda and a fight against corruption, and came to be seen as a generational and cultural alternative to GERB. Finally, after three consecutive inconclusive elections, at the end of 2021 Petkov managed to form a coalition government consisting of his party, ITN, the BSP and the liberal Democratic Bulgaria (DB) party.

When in December 2021, after many months of crisis, Petkov formed a government which had a stable parliamentary majority and enjoyed President Radev’s support, and promised a series of reforms, a section of Bulgarian public opinion and the country’s EU partners saw this as a chance for overcoming the crisis, raising hopes that reforms to the state could finally be carried out. The government took decisive action against corruption, prepared for entry into the eurozone and made efforts to normalise relations with North Macedonia (under Borisov’s government, , Bulgaria had blocked the start of this country’s EU accession negotiations from 2020 to 2022). The Russian invasion of Ukraine came as a major test for the new government and caused the first cracks in the coalition. The BSP was reluctant to support Petkov’s policy of decisively supporting Kyiv, and President Radev was also (and still is) opposed to providing military assistance to Ukraine[4]. The most serious government crisis occurred in June 2022, when the ITN unexpectedly left Petkov’s cabinet, leading to its collapse[5]. Consequently, the country was governed by two interim cabinets appointed by Radev for nearly a year.

Another ultimately unsuccessful attempt to stabilise the political system was made after the early elections in April 2023. Following two months of negotiations, the two largest and competing parliamentary forces, GERB and the PP-DB, decided to form two rotating governments (June 2023 – March 2024 and March–November 2024)[6]. However, these parties were able to continue cooperation for just half of this period. It is worth noting that when the first ‘rotating’ cabinet was in power, both the GERB and PP-DB politicians emphasised that it was not a classic ‘grand coalition’ like those familiar from Germany or Austria. Instead, they called it a ‘sglobka’ ( сглобка), a term that is difficult to translate precisely, meaning a temporary combination of two completely different elements. This ‘non-coalition coalition’ of GERB and the PP-DB was indeed an attempt to reconcile fire with water in personal terms, as the PP represented a generational antithesis to GERB, since it had been formed in response to the widespread corruption practices during Borisov’s rule. Despite this, the two parties did find something in common: their Euro-Atlantic orientation (a crucial factor in the complex international situation) and their desire to weaken the president’s position. When the Denkov government linked to the PP-DB resigned in March 2024, politicians representing the two parties were unable to reach a compromise on the composition of the second rotating cabinet, which was supposed to have been led by Mariya Gabriel from GERB. Consequently, since April this year, the country has once again been governed by an interim government appointed by President Radev under the new constitutional conditions[7].

Two struggling camps and chances for compromise

Based on the dynamics of the political crisis in Bulgaria, which has been ongoing since 2021, two relatively broad camps can be distinguished. One camp aims to stabilise the executive institutions, which in turn would lead to reforming the malfunctioning areas of the state step by step (especially improving the functioning of the judiciary), while also remaining a predictable and serious ally in Euro-Atlantic institutions. This is particularly important during the ongoing Russian-Ukrainian war. The other political camp derives real benefits from the instability, as this allows it to continuously postpone state institutional reforms and makes it possible to adopt a vague and non-committal stance in the face of major international challenges. This particularly concerns regional security in the Black Sea and the Russian threat, which a significant portion of the political class has long underestimated.

The fluid boundaries between these two camps pose a major difficulty. The clear opponents of changes aimed at stabilising parliamentary governance include President Radev, the nationalist and pro-Russian party Revival (which is currently the fourth largest party in the current, shortened parliament) and the BSP. Such changes are also opposed by the vast bureaucratic-business apparatus, which has strong ties with the influential energy lobby focused around the president and the country’s leading oligarchs. GERB, which for many years was entangled in corruption schemes and pursued a rather ambiguous policy towards Russia until 2022, appears to have made a lasting shift since February 2022. This shift involves a commitment to state modernisation and firmly anchoring Bulgaria within the Euro-Atlantic community. However, GERB is still reluctant to hold people from Borisov’s circle accountable for their involvement in past corruption.

The PP has contested GERB’s rule since its establishment, and initially enjoyed President Radev’s tactical support. Radev was one of the initiators of the coalition formed at the end of 2021, which included the PP, the Socialists, ITN and DB (the latter at the time functioned as a separate party until merging with the PP in 2023). However almost immediately after Russia invaded Ukraine, Radev, who was reluctant to provide military aid to Kyiv or to pursue energy and resource independence from Russia, came into conflict with the PP. He supported those factions within Petkov’s cabinet (mainly the Socialists and ITN) that were opposed to Bulgaria’s greater involvement in aiding Ukraine and NATO’s allied policies.

There are still strong personal animosities between Borisov and Petkov, and between the leaders of GERB and the PP-DB, which have also affected the political culture and governance model. Despite this, external circumstances related to the invasion of Ukraine have brought the two parties closer together, as they share the desire to firmly anchor Bulgaria in Western political and economic institutions.

The rivalry between GERB and the PP-DB, which currently marks the main dividing line in Bulgarian politics, is therefore not ideological; nor does it concern any fundamental differences over international policy. Both factions share similar conservative-liberal political roots and have developed in opposition to the policies seen in the first years of Bulgaria’s post-Communist transition. A distinct political role is played by the party representing the Turkish minority. Over the past nine months it has not joined Denkov’s government, though it has supported its reform efforts: the constitutional amendments to limit President Radev’s powers over interim governments; the judicial and secret services reform; the reforms leading to the adoption of the euro, entry into the Schengen Area and joining the OECD; and providing military and humanitarian aid to Ukraine.

In this way, the achievements of Denkov’s rotating government demonstrate that, despite the disputes and animosities, the two political parties which are leading in the polls have the potential to govern together and play a constructive role within Euro-Atlantic structures. However, the personal disputes and the differences in their aspirations to reform may stand in the way. There is still strong antipathy between the key politicians of both parties. GERB is reluctant to support efforts to address corruption scandals from the time when it governed the country on its own, and it used procedural measures to sabotage the work of the parliamentary committees dealing with corruption and organised crime when the rotating government was in power.

Where is Bulgarian democracy heading?

Given the political crisis, it is increasingly difficult for the existing parties to capitalise on public disillusionment with the instability of the political scene. Instead, they form typical interest groups, serving narrow clienteles who maintain their status through participation in politics and the allocation of positions to them in various institutions and companies. In this respect, politics is viewed by the general public as an instrument for implementing individual survival strategies in one of the EU’s poorest countries. Opinion polls published in March show that although 51% of Bulgarians believe that parliamentary democracy is the best possible system, despite its flaws, only 13% are convinced that politicians really serve the interests of society[8].

Government instability and frequent snap elections are not unusual in today’s democracies. However, the governments in Bulgaria, which has faced similar crises in past decades, have been consistently incapable of forming a stable majority since 2021. As a result the country has been in fact governed by the president, even though it is a parliamentary republic. GERB and the PP-DB maintain a roughly constant share of supporters, each garnering around 25% of the vote, with slight fluctuations giving one party a lead over the other in successive elections. The electorates of both of these major parties are quite clearly socially rooted: GERB is mainly supported by older, less-educated voters from smaller towns, while the PP is backed by younger people and residents of large cities[9]. Furthermore, shifts between the electorates of these parties are insignificant.

The other parties, the DPS, the BPS, Revival and Democratic Bulgaria, have relatively stable groups of supporters ranging from 7 to 14% of the total electorate. Before almost every election since April 2021 new forces have emerged in parliament, their profiles mostly being nationalist-conservative or anti-establishment, such as There Is Such a People (ITN) or Arise, Bulgaria! (VB). However, they have quickly lost support and have often failed to pass the threshold in subsequent early elections, as was the case with ITN in October 2022. The political left, which is still centred around the BPS, is facing an increasingly serious crisis, and the number of its supporters, predominantly representing the older generation of Bulgarians, is constantly shrinking. There was a split in the party before the April 2023 elections, but no new party of this profile emerged in parliament as a result of it. In turn the pro-Russian party Revival, which has been boycotted by all other Bulgarian political parties, has nevertheless been gaining in the polls since Russia invaded Ukraine, and is now the third most popular political force in the country[10], partly due to its criticism of the policy of sending military aid to Kyiv [11].

As a result of the frequent elections, the Bulgarian public has become noticeably disenchanted with voting and has been continuously losing confidence in the entire political class, and the prestige of the profession of politician has been declining. Between the election in April 2021 and that in October 2022, voter turnout fell by over 10 percentage points, reaching its lowest level since 1990 (39%). The turnout was slightly higher (40%) in the elections on 2 April 2023.

The paradox of the current situation is that, despite a range of formal difficulties and their undoubtedly reduced authority on the international stage, both the interim governments and the short-lived parliamentary cabinets have managed to take significant steps to ensure energy security under challenging external conditions (including gas diversification); to increase state control over the fuel sector by assuming supervision of the Lukoil-owned Neftohim refinery in Burgas; to maintain military assistance to Ukraine; and to continue the modernisation of the armed forces (2023 was the first year when the country reached the 2% of GDP defence spending threshold).

The most important achievements of the GERB–PP-DB rotating government include the constitutional reform and the continuation of allied policy within NATO, both through military assistance to Kyiv and the ongoing modernisation of the technologically outdated armed forces. However, all these reforms require consistent daily implementation, which cannot be accomplished without a stable executive power. This especially concerns the fights against corruption and organised crime, which must be supported by an effective and predictable state.

Despite these achievements over the past three years, ongoing political instability hampers the systemic resolution of many of Bulgaria’s problems. Seventeen years after joining the European Union, the country still faces challenges related to economic and institutional reforms. The fragile democratic culture and the lack of stability in the executive will continue to hinder effective policy-making, especially given the current international situation.

APPENDIX

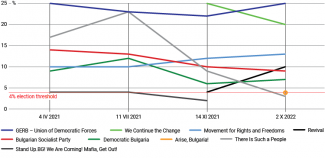

Chart 1. Bulgarian parliamentary election results in 2021–2022

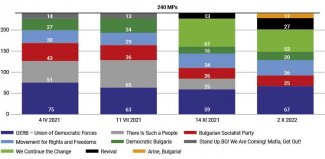

Chart 2. Distribution of seats in Bulgarian parliament after the elections in 2021–2022

Source: Bulgarian Central Electoral Commission (CIK), cik.bg.

[1] See Konstytucja Republiki Bułgarii, Article 99, translated by H. Karpińska, Wydawnictwo Sejmowe, Warsaw 2012, libr.sejm.gov.pl.

[2] For more details see Ł. Kobeszko, ‘Amendments to the Bulgarian constitution: a way to overcome the political crisis’, OSW, 5 January 2024, osw.waw.pl.

[3] See M. Spirova, Bulgaria: Political Developments and Data in 2019, European Consortium of Political Research, 10 November 2020, ejpr.onlinelibrary.wiley.com.

[4] For more details, see Ł. Kobeszko, ‘Bułgaria wobec agresji na Ukrainę’, OSW, 15 April 2022, osw.waw.pl.

[5] Idem, ‘Kryzys rządowy w Bułgarii’, OSW, 17 June 2022, osw.waw.pl.

[6] Idem, ‘Temporary stabilisation? Bulgaria's new government’, OSW, 7 June 2023, osw.waw.pl.

[7] Idem, ‘Bulgaria: a failed government reshuffle and another early election’, OSW, 11 April 2024, osw.waw.pl.

[8] See Моментна картина на масовите нагласи към политиката, Gallup International, 15 March 2024, gallup-international.bg.

[9] See March 2017 poll results, 28 March 2017, news.bg.

[10] See August 2023 poll results, Агенция Стандарт, 31 August 2023, standardnews.com.

[11] See Обобщени данни от избор на народни представители, Централната избирателна комисия, 3 October 2022, cik.bg.