An increasingly important partner. Poland’s exports to and investment in Ukraine

The Russian invasion of Ukraine has caused a surge in Polish-Ukrainian trade, mainly due to an increase in Polish exports which grew by more than 80% between 2021 and 2023. Poland’s imports have remained at pre-war levels, with the exception of a spike recorded in 2022 due to an influx of cereals and oilseeds. In 2023, the value of Poland’s exports to Ukraine was almost triple that of its imports from that country. At present, Ukraine ranks sixth among Poland’s export partners. Although the increase in exports was mainly recorded in categories such as weapons, ammunition and fuels, more dynamic export activity also occurred in numerous other sectors, including clothing, footwear and furniture. Despite periodic border blockades, road and rail transport played a key role in trade and no noticeable disruptions in export activity to Ukraine were recorded.

Poland is Ukraine’s 10th largest foreign investor. This is a very good result because several countries higher on this list are involved in a return of Ukrainian capital. Polish investment projects are worth a total of $780 million and mainly involve the manufacturing industry, finance and trade. When the war broke out, few new investment projects were launched in Ukraine and mainly by companies which had operated there before the invasion. Other potential investors, not yet present there, have adopted a wait-and-see attitude, prompted by uncertainty regarding the progress of the war and Ukraine’s political future, as well as the persistently unfavourable conditions for doing business there.

Poland’s trade with Ukraine

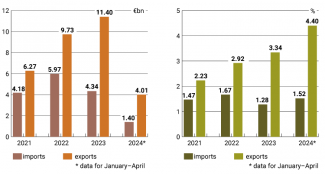

The Russian invasion of Ukraine has triggered a rapid increase in Polish commodity exports there (see Chart 1). These increased by 54% in 2022 and by a further 17.5% in 2023. If the trend recorded in the first four months of 2024 continues, it can be expected that between 2021 and 2024 the value of Polish exports to Ukraine will almost double. Poland’s commodity exports to Ukraine grew much faster than to other markets. As a consequence, Kyiv’s importance as an export partner for Poland increased in value from 2.2% in 2021 to 4.4% in January–April 2024.

As regards commodity imports from Ukraine, the situation is different. In 2022 these increased by 42.9% mainly due to an influx of cereals and oilseeds, which Poland had practically not imported from that country before the war. However, in 2023, as a result of Poland’s decision to impose restrictions on the import of some categories of produce, the imports fell by 28.3% to slightly above the 2021 figures. If the trend recorded in the first four months of 2024 continues, imports will remain the same as last year.

The balance of trade in commodities is thus steadily growing in Poland’s favour. While its trade surplus stood at €2.1 bn in 2021, in 2023 it reached €7.1 billion. This means that in 2023 the value of the goods Poland exported to Ukraine was almost three times the value of its imports from Ukraine.

Chart 1. Value of trade between Poland and Ukraine and Ukraine’s share in Poland’s total commodity trade

Source: Eurostat.

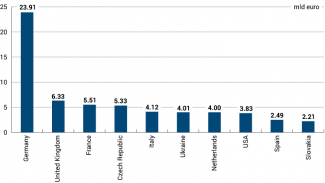

Ukraine’s importance for Polish exports is growing. This is corroborated by figures regarding their geographical structure. In 2021, Ukraine ranked 15th among Poland’s export partners, in 2023 it moved up to seventh place, and after the first four months of 2024 it ranked sixth, slightly behind Italy and ahead of the Netherlands and the US.

Chart 2. Ten biggest recipients of Poland’s exports in the period between January and April 2024

Source: Eurostat.

The characteristics of Poland’s exports

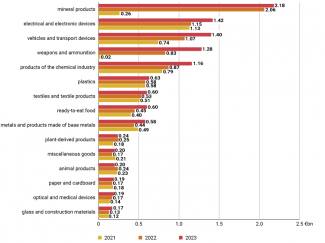

The Russian invasion has also caused a significant shift in the structure of Poland’s commodity exports to Ukraine. The sale of mineral products (mainly fuels) grew severalfold, and that of armaments increased even more. Poland recorded a major increase in its export of vehicles and transportation equipment as well as products of the chemical industry (especially fertilisers and plastics). At the same time, in several other commodity groups the increase was minor or the exports actually fell (for example in categories such as livestock products and plastics).

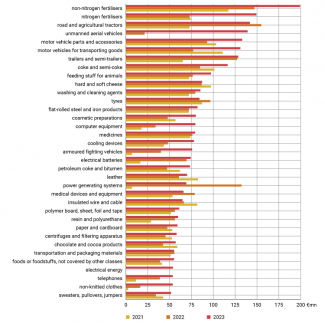

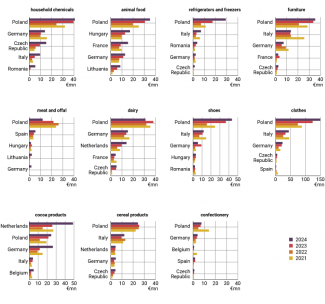

Chart 3. Comparison of export volumes of Poland’s main commodity categories to Ukraine in 2021–3

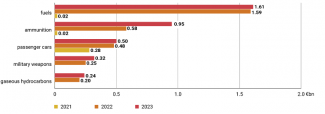

In 2023, almost 60% of Polish exports to Ukraine involved 40 of the most important commodities, and five major categories accounted for 32% of these exports (see Charts 4 and 5). A surge in these exports, which was recorded following the outbreak of the war, was mainly due to goods which are directly or indirectly linked to the war, that is weapons and ammunition, fighting vehicles and UAVs.

Fuels are another key commodity which Poland exports to Ukraine. As a result of Russian shelling of a refinery in Kremenchuk, the local production of fuels has decreased significantly since April 2022. Passenger cars are another important category (a major proportion of them is sent to the front), alongside batteries and power generators (the demand for which has increased due to damage to energy infrastructure occurring since autumn 2022).

Chart 4. Poland’s five most important commodity exports to Ukraine

Source: Eurostat.

The export figures for most of the remaining major commodity categories showed a much less significant increase or fell.

It can be assumed that large exports of war-related goods will only continue as long as the conflict is in its hot phase. As regards fuels, this period may last several years following the end of the conflict until Ukraine rebuilds its own refinery.

Chart 5. Poland’s most important commodity exports to Ukraine – positions 6–40

Source: Eurostat.

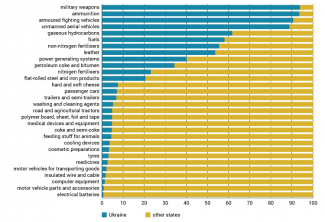

The Ukrainian market is of huge importance for the sale of goods directly linked to military activity (ammunition, weapons and armoured vehicles) because its share in Poland’s total exports in these categories exceeds 90%. For UAVs, the share is also very significant, although most likely it involves Polish companies re-exporting devices imported from other countries (mainly Turkey and China). Alongside this, as regards the majority of other types of goods, exports to Ukraine are minor or even insignificant.

Chart 6. Ukraine’s share in Poland’s total exports in selected categories in 2023

Source: Eurostat.

It should be emphasised that Ukraine’s ability to substitute its imports from Poland is limited. As regards commercial armaments supplies, Poland’s competitors are difficult to assess because it is one of the few EU member states to publish figures on these exports and Ukrainian statistics do not include this category at all. As regards fuels, Poland is the top exporter among all EU member states and is one of the two routes of their transit, alongside Romania. Compared with their competitors, in particular those from other EU member states, Polish exporters’ main advantage includes their geographical proximity (which reduces the cost of logistical operations), the wide array of exported goods alongside their attractive quality-to-price relation, and their knowledge of the Ukrainian market.

Poland’s exports according to means of transport and the border blockade

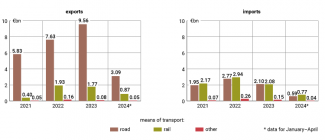

Before the war, road transport played the leading role in the export of Polish goods to Ukraine.[1] Starting from 2022, its importance began to grow rapidly, although the use of rail transport increased significantly alongside it, having previously been almost insignificant.

Chart 7. Value of Poland’s trade with Ukraine according to means of transport

Source: Eurostat.

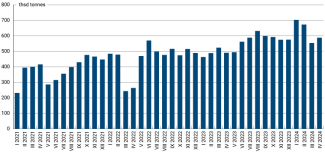

Between November 2023 and January 2024, a blockade of road border crossings occurred. It was organised by representatives of Polish carriers, who protested against the operation of their Ukrainian counterparts and accused them of unfair competition. From January until the end of April 2024, Polish farmers blocked several border crossing points. However, these developments had no measurable impact on the volume of Polish exports to Ukraine. Measured in tonnes, in the first four months of 2024 Poland’s exports to Ukraine in fact grew.

Chart 8. Monthly volumes of Poland’s exports to Ukraine between January 2021 and April 2024 (in tonnes)

Source: Eurostat.

It is clear that Polish exporters have very quickly adapted to the new conditions for doing business in terms of the means of transport. Starting from November 2023, when the road blockades began, a major proportion of exports switched to rail transport. This enabled Polish exporters to maintain the volume of their exports, especially bulk goods (such as fuels) which are relatively easily transported by rail.

At the same time, numerous companies (including Polish businesses operating in Ukraine) were unable to modify their operations in this manner, which exposed them to losses resulting from their failure to meet delivery deadlines and from (an up to three-fold) increase in the cost of logistical operations linked with re-routing their exports to other EU member states bordering Ukraine. According to Polish businesses operating in Ukraine, Warsaw should make every effort to avoid similar blockades of border crossing points in the future.

Chart 9. Monthly volumes of Poland’s exports to Ukraine between January 2021 and April 2024 (in tonnes) according to means of transport

Source: Eurostat.

In September 2023, when Poland unilaterally decided to extend the ban on importing cereals and oilseeds, the government in Kyiv threatened to introduce an embargo on Polish-grown fruit and vegetables, although finally it did not do this. In 2024, in response to the Polish border blockade, it also considered banning the import of selected agri-food categories from Poland, such as dairy products and fruit, but again ultimately did not decide to do so. Representatives of Polish businesses operating in Ukraine complained that their competitors attempted to take over their clients by emphasising that these should not cooperate with companies with Polish capital. However, these attempts proved unsuccessful and ceased when the blockades ended.

Although users of Ukrainian social networks occasionally call for a consumer boycott of Polish-made goods, an analysis of Poland’s exports to Ukraine indicates that these calls are not successful. However, in the first four months of 2024 the sale of some products, which (unlike, for example, fuels) can relatively easily be identified as having been made in Poland, did fall (see Chart 10). This mainly involves meat and dairy products, although dairy fell less significantly. Most likely, this decrease was not caused by reluctance on the part of Ukrainian consumers but was due to extended delivery times resulting from the border blockade (which is highly important for perishable foodstuffs) and the fact that the exporters’ competitors benefited from this situation. Moreover, for the majority of commodity exports an increase was recorded, for example in 2024 the sale of Polish-made clothes and shoes to Ukraine is much bigger than before the war. Given that around 6 mn individuals have left Ukraine since February 2022, the Ukrainian market’s demand for Polish-made goods should be assessed as high.

Chart 10. Comparison of selected commodity exports from EU member states to Ukraine in the period between January and April of the given year

Foreign direct investment (FDI) in Ukraine

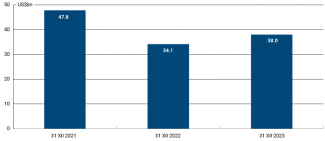

According to statistics compiled by the National Bank of Ukraine (NBU), in 2023 accumulated FDI (excluding debt instruments) amounted to $38 bn, which indicated that they grew by 11.4% year-on-year. In 2022, compared with 2021, they fell by $13.7 bn (down 28.6%) and stood at $34.1 bn.

Chart 11. Accumulated FDI in Ukraine

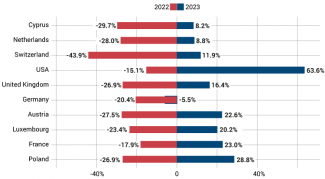

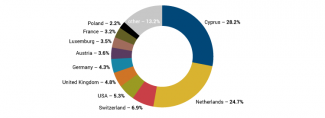

As in previous years, Cyprus is the largest investor accounting for 32.5% of the FDIs. These investment projects mostly involve returning Ukrainian capital. This practice has also been recorded for investment carried out by other states, including Luxembourg and the United Kingdom, where Ukraine’s biggest oligarchs have formally incorporated some of their businesses. Other important investors include the Netherlands (28.3%) and Switzerland (8.2%).

Due to the Russian invasion, 2022 saw a drop in FDI carried out by all of the largest investors in the Ukrainian economy. For Cyprus it fell by 29.7%, for the Netherlands by 28%, and for Switzerland by 43.9%. A less significant decrease was recorded for Germany (20.4%), the US (15.1%) and France (17.9%).

Chart 12. Change in accumulated FDI carried out by main investors in 2022 and 2023 (y/y)

Source: National Bank of Ukraine.

2022 saw a significant decrease in FDI in the most important sectors of the economy including the manufacturing industry (32.9%), the mining industry (28.5%) and the finance and insurance sector (41.9%). Only a minor drop was recorded in the IT sector (5.2%).

The agricultural sector performed relatively well (15.9%), although in this case it is difficult to assess the situation in a reliable manner. FDI in the agricultural sector is relatively insignificant ($1.5 bn according to figures as at the end of 2022, which accounted for 4.5% of investment carried out in Ukraine). Cyprus accounted for 26.6% of these investment initiatives and Luxembourg for 22.4%, which indicates that their end beneficiaries were mainly Ukrainian citizens. Additionally, investment projects carried out by some states (such as Saudi Arabia) have been classified and excluded from publicly available statistics. Furthermore, in the Ukrainian register of legal persons the majority of big businesses with foreign capital operating on the agricultural market, such as Cargill, LDC, Corteva and Viterra, indicated trade in cereals as their principal business activity. They are thus included in the statistics for FDI carried out in the wholesale and retail trade sector and the publicly available NBU statistics do not present them as a separate category.

In 2023, when the economic situation stabilised, the scale of investment in Ukraine increased. However, for all of the most important investor states except for the US and France, it was still smaller than at the end of 2021.

Chart 13. Comparison of accumulated FDI carried out by ten most important investors in 2021–3

Source: National Bank of Ukraine.

In Q1 2024, the geographical structure of foreign investment carried out in Ukraine did not change significantly compared with the end of 2023. Their increase in value was also insignificant: from $38.0 bn to $38.7 bn.

Chart 14. Share of specific states in FDI carried out in Ukraine at the end of Q1 2024

Source: National Bank of Ukraine.

Foreign direct investment is unevenly distributed in terms of the geographical location. As at the end of 2023, as much as 40.6% of these projects, worth $15.4 bn, were located in the city of Kyiv. Aside from the capital city, other important areas in which they are concentrated include the following regions: Dnipropetrovsk – 16.4%, Lviv – 5%, Kyiv – 4.8% and Poltava – 4.7%. The NBU does not publish information on foreign investment in Donetsk, Luhansk and Kherson regions, as Russia occupies large swathes of the territory there. The remaining 16 regions account for 18.8% of FDI.

The characteristics of Polish investments

At the end of 2023, Poland’s accumulated investments in Ukraine were worth $780 mn. They accounted for 2.6% of FDI there, which made Poland Ukraine’s 10th largest foreign investor. More than 600 companies with Polish capital operate in Ukraine. Kyiv is interested in attracting Polish investments. Despite the tensions in bilateral relations triggered by trade restrictions imposed by Warsaw and temporary border blockades, over the last two years there have been no reports suggesting that Ukrainian tax bodies and fiscal services interfered in the activity of Polish companies operating in Ukraine.

Although the total value of Polish investment may seem insignificant, their importance exceeds their nominal value. This is due to the return of Ukrainian capital from tax havens such as the British Virgin Islands and Belize, as well as from selected EU member states which have a major share in Ukraine’s FDI.

Polish investments in Ukraine are mainly concentrated in three sectors. The manufacturing industry is the most important one: Cersanit operates a manufacturing plant of ceramic sanitary ware in Zviahel, Barlinek owns a production plant of floorboards in Vinnytsia, and window manufacturer Fakro has a production plant in Lviv region. At the end of 2022, Polish investment in the Ukrainian manufacturing sector accounted for 4.1% of FDI (more recent data is unavailable).

The finance and banking sector is another important area of investment activity: KredoBank, controlled by PKO BP, is Ukraine’s 14th largest bank, and in the insurance sector companies worth noting include PZU Ukraina (in 2023 it ranked sixth in this sector in terms of assets) and PZU Strakhuvannya Zhyttya (Ukraine’s third largest life insurance company). At the end of 2022, Polish investments accounted for 5.4% of FDI in the finance sector.

In the retail trade sector, the company LPP is an important investor (it owns brands such as Reserved, Cropp, House and Sinsay). In 2023, it controlled around 10% of the sale of apparel in Ukraine. At the end of 2022, the total share of investments with Polish capital in the wholesale and retail trade sector was 2%.

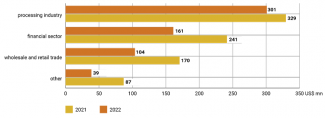

Chart 15. Change in the value of Polish FDI in specific sectors

Source: National Bank of Ukraine.

Foreign investment in Ukraine following the outbreak of the war

Although FDI fell after the launch of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, it did not become entirely absent there. Starting from 2022, investment projects have mainly been carried out by businesses which had operated in Ukraine in the preceding years. This primarily involves companies from EU member states, the US and Canada. Turkey is another highly active investor.

Several specific examples are worth mentioning: in June 2023 the US company Philip Morris International launched construction of a new cigarette production plant, which opened in May 2024. Worth $30 mn, the facility was located in Lviv region. However, another of the company’s plants situated in Kharkiv ceased to operate due to safety concerns. In March 2024, Britain’s Unilever began to develop a cosmetic manufacturing plant in Bila Tserkva. The €20 mn investment is intended to enhance the company’s business development in Ukraine. In March 2023, Germany’s Bayer announced a €60 mn investment to expand its corn seed production facility in Pochuiky in Zhytomyr region. The project includes the construction of a new seed drying facility, installation of state-of-the-art agricultural equipment and the expansion of storage facilities. The initial phase of this investment project (worth €35 mn) was completed in March 2024. In 2023, Continental Farmers Group, a Saudi agroholding, invested €60 mn primarily in the expansion of storage facilities for agricultural produce. Planned or completed investments also include projects carried out by companies from Ireland (Kingspan – construction materials), Turkey (Onur Group – mining and renewable energy), Germany (Fixit – construction materials) and Switzerland (Nestlé – foodstuffs).

It is likely that in the coming months, Xavier Niel, a French billionaire and owner of numerous businesses including the Play mobile network operating in Poland, will buy Lifecell, Ukraine’s third largest mobile operator in terms of the number of users, which is currently owned by Turkey’s Turkcell. The estimated value of this transaction is $525 mn. If this happens, it will be the largest acquisition in a decade.

Polish companies continued their investment activity in Ukraine after the outbreak of the war. In 2023, Cersanit completed the construction of a new production line worth €20 mn, which is expected to boost the plant’s production capacity by 20%. This was the company’s biggest investment in Ukraine since the facility’s inauguration in 2007. As at the end of 2023, LPP operated more than 100 stores there and announced its plan to double its presence by the end of 2024, mainly by launching the Sinsay brand on the Ukrainian market. Despite a suicide drone attack on Fakro’s manufacturing plant located in Lviv in September 2023, as a result of which fire destroyed a production hall and a warehouse (losses were estimated at PLN30 mn), the company does not intend to withdraw from Ukraine. Moreover, it plans to develop new production lines. However, it is difficult to cite examples of major investments carried out by companies that did not operate in Ukraine before the outbreak of the war. Similarly, there are no reports which could confirm that a single Polish company has used the insurance assistance provided by the Export Credit Insurance Corporation (KUKE). This programme is guaranteed by the state treasury and is aimed at companies doing business in Ukraine.

Due to the ongoing war, Kyiv has made continuous attempts to attract foreign investors operating in the armaments industry, in particular from the United States, Germany, France and the United Kingdom. Over the last two years, representatives of various companies from these countries, and also from Turkey, have announced several projects which envisaged locating at least a portion of their production activity in Ukraine. However, the vast majority of these projects have not evolved further than the relevant memorandums, and the implementation of already signed agreements is being delayed. As a consequence, only isolated investments are actually implemented. The biggest investment project revealed so far involves the ‘armoured weapons repair and production’ hall, which was launched in June 2024 by Germany’s Rheinmetall and the company Ukrainian Defence Industry. This facility is where the lighter military vehicles Germany has donated to the Ukrainian army (up to and including the Marder infantry fighting vehicle category) will be maintained and repaired.

The future of foreign direct investment in Ukraine

In the second half of 2022, when the prospect of an end to the war did not seem very distant and many observers pinned their hopes on Ukraine’s reconstruction (the value of this venture was estimated at hundreds of billions of dollars), a temporary increase in investors’ interest in entering the Ukrainian market was noted. Although Ukraine is consistently trying to attract FDI, including from Poland, 2023 saw a drop in investor interest, which resulted from the diminishing likelihood of a quick end to the hostilities. Moreover, Ukraine’s investment climate has not improved significantly. As in the years preceding the Russian invasion, the state is grappling with corruption, an inefficient judiciary and pressure from the law enforcement bodies.

Thus, the vast majority of potential new investors have decided to adopt a wait-and-see attitude and to temporarily halt their investment plans. Projects are being postponed until after the end of the hostilities, when the situation in the region stabilises permanently. There are many indications that Polish companies have adopted a similar strategy. When the war ends, investment in housing and road infrastructure will be among the most important fields of cooperation. Other promising sectors include energy, especially renewable energy sources, and agriculture and the food industry.

[1] This also involves trade in self-propulsion machines, which includes various types of vehicles.