Game over? The future of Russian gas transit through Ukraine

Ukraine’s seizure of a portion of Russian territory containing strategically important gas infrastructure assets has not resulted in a reduction of Russian gas flow to EU consumers. However, the rising security risks along this route in recent weeks have fuelled questions about the future of Russian gas transit through Ukraine after the current transit agreement expires at the end of 2024, as well as the potential impact of the forthcoming changes on the stability of supplies.

In light of the ongoing Russian-Ukrainian war and the divergent interests of the key parties involved (Ukraine, the European Union, and Russia), there is a high degree of uncertainty regarding the future use of Ukraine’s gas pipelines. Given the unpredictability and evolving nature of the conflict, it is conceivable that Russian gas transit could cease entirely even before the end of this year. Any disruption of supplies in the coming weeks, or from January 2025, is likely to trigger at least a short-term spike in prices and raise uncertainty in the EU market. This would also accelerate the EU’s shift away from its dependence on Russian hydrocarbons, thereby reducing the associated political risks.

The Ukrainian offensive and the stability of supplies

Following its military incursion into Russia’s Kursk Oblast on 6 August, Ukraine has gained control of parts of the infrastructure vital for the continued transit of Russian gas. This includes a section of the gas pipeline running into Ukraine, the Sudzha border post (where gas currently passes before transiting through the Ukrainian network to the EU), and a metering station. Although some facilities, including a short overland section of the pipeline, have been damaged, this has not significantly reduced or halted the transport of gas.

There was a brief reduction in gas flow in the initial days following the Ukrainian offensive. The lowest recorded level, 37 million cubic metres per day (approximately 14% below the average of the preceding weeks) was noted on 9 August. However, a few days later, the flow returned to normal levels.

Chart 1. Daily gas flows through the Sudzha metering point

Source: OGTSU.

Since 11 May 2022, when Ukraine stopped receiving Russian gas at Sokhranivka, Sudzha has remained the only operational border point between Ukraine and Russia through which gas continues to flow to Europe, despite the ongoing war. According to the Ukrainian operator OGTSU, prior to Russia’s full-scale invasion, the technical capacity of the country’s infrastructure was 244 million cubic metres per day, with an average of 130.1 million cubic metres of gas transported per day in 2020. The volumes shipped in recent years have been lower than those stipulated in the agreement, which remains in force until the end of 2024 (see Appendix).

The future of transit: the stakeholders’ interest

The ongoing hostilities near strategic gas facilities, the resulting damage, and Ukraine’s seizure of these assets have provided both Ukraine and Russia with a pretext to halt transit earlier than the agreement stipulates. However, the continued flow of gas suggests that neither party currently has an interest in discontinuing supplies via this route. The future of Russian gas shipments through Ukrainian territory and the use of Ukrainian infrastructure depends on the developments on the battlefront and, perhaps to an even greater extent, the interests and actions of the countries involved.

Despite the fighting on its territory near sensitive gas facilities and damage to this infrastructure from shelling, Ukraine has maintained a stable transit of gas from Russia to the EU since the outbreak of the war. At the same time, the Ukrainian government has officially rejected the possibility of extending the current agreement or signing any documents directly with Russian entities. President Volodymyr Zelensky reiterated this in a July interview with Bloomberg, while also stating that other options for using the country’s infrastructure were under consideration, including gas supplies from Azerbaijan,[1] (see Appendix). In an interview on 6 August, the head of Naftohaz, Oleksiy Chernyshov, also admitted that talks on gas shipments were ongoing with the Azerbaijani company SOCAR, although he did not specify the volumes being discussed.[2] He further noted that it could be possible for EU companies to purchase gas from Gazprom at the Ukrainian-Russian border.

Most experts in Ukraine oppose extending the transit of both Russian gas and any other fuel flowing from Russia, including potential gas supplies from Azerbaijan. Serhiy Makogon, the former head of OGTSU and a prominent figure in this field, has highlighted that Russia earns significantly more from the sale of gas transiting Ukraine than Ukraine earns from the transit itself. Reportedly, no more than 20% of this revenue goes to the Ukrainian budget, with the remainder covering the costs of managing the process, such as purchases of technical gas, personnel salaries, and maintenance work.[3]

At the same time, Ukraine has been taking steps to prepare its gas pipeline system for the possibility of a complete halt in Russian transit. The results of the 2023–24 stress tests indicate that Ukrainian infrastructure is capable of operating in reverse mode – handling supplies solely from the western direction. Legal changes adopted in August allow OGTSU to optimise the use of its facilities’ capacity and adjust it to meet domestic consumer demand, which would likely involve shutting down redundant compressor stations to reduce maintenance costs. Currently, only 10% of the system’s design capacity is being utilised.

The European Commission and the vast majority of EU member states have supported Ukraine’s decision not to extend its agreement with Russia. This aligns with the EU’s goal of completely phasing out imports of Russian hydrocarbons, a policy reaffirmed by the President of the European Commission, Ursula von der Leyen. However, some individual countries, notably Hungary, remain sceptical of this approach. In addition, several EU member states (Slovakia, Austria, to a lesser extent the Czech Republic, Hungary, Croatia, Slovenia, and Italy) continue to depend to varying degrees on the transit of Russian gas through Ukrainian territory. For some of these nations, maintaining the option of importing gas from Russia via Ukrainian pipelines is economically advantageous; others, such as Slovakia, continue to benefit financially from transit, although the flows and profits are much lower than they were before the war.

At the same time, countries that still rely on Russian gas supplies through Ukraine have been preparing for the expiration of the Ukrainian-Russian agreement and the likely termination of transit. Consequently, they have signed contracts for alternative supplies, such as LNG or gas from Norway, and have been exploring other routes. In recent months, there have been discussions about the possibility of importing gas from Azerbaijan, which could be transported to consumers in Central Europe via Ukrainian pipelines. However, it remains unclear how this would function, including the specific route such shipments would take and whether this would involve physical transit or swap transactions. Nevertheless, the initiative has garnered significant interest within the EU and received support from the European Commission.

For Russia, the loss of control over the Sudzha metering station has provided a pretext to halt its shipments through Ukraine, as it is now impossible to accurately measure how much gas is entering the Ukrainian network. Despite this, Gazprom has chosen not to take this step, and gas transit has continued. This decision is primarily driven by the profitability of the EU market, which has become especially important given Gazprom’s financial difficulties since 2023.[4] Gas sales to the EU via this route generate approximately $2bn, accounting for around a quarter of the company’s export revenue. Additionally, Russia currently lacks the infrastructure to divert all the gas flowing through Ukraine to alternative routes, due to capacity constraints with TurkStream and political limitations affecting the idle Yamal pipeline and one undamaged line of Nord Stream 2.

Therefore, Gazprom has sought to continue, and potentially even increase, its transit through Ukraine, at least until it is able to divert its sales to other markets or find a viable option to bypass Ukraine’s territory. By doing so, the company has also avoided the need to further cut its production.[5] For the Russian government, the transit of gas serves as a means of exerting political pressure on the EU and specific European countries that still rely on Russian gas, such as Austria, Hungary, and Slovakia. These strategic interests are reflected in the recent changes in Gazprom’s delivery patterns: since Q4 2023, the company has reported increases in shipments after a period of significant reductions that began two years earlier.

Chart 2. Quarterly shipments of Russian gas through Ukraine to the EU from 2021 to mid-2024

Source: Bruegel.

As the transit agreement nears expiration, the Kremlin seems interested in exploring any economically and politically viable option to ensure the continued transit of its gas. On a rhetorical level, Russia has accused Ukraine of being unwilling to extend exports, despite what it portrays as goodwill on Moscow’s part.[6] Therefore, we can expect Russia and Gazprom to be open to proposals from EU actors regarding the sale and transport of gas through the Ukrainian network under revised terms. For instance, Gazprom might be willing to sell its gas directly to EU buyers at the Russian-Ukrainian border.

Regardless of the future of transit through Ukraine, Russia may also consider facilitating the supply of Azerbaijani gas to the EU via Russian and Ukrainian pipelines. Although this could introduce competition in the EU market, Russia might perceive both political (as a tool to influence the EU and Azerbaijan) and financial (from transit revenues) advantages to agreeing to transport this gas. However, Russia could also choose to minimise or halt its shipments altogether, avoiding any arrangements that might harm Gazprom’s commercial interests. In this way, the Kremlin could attempt to create divisions within the EU over its sanctions policy and support for Ukraine, while also driving a wedge between Ukraine and the EU by holding the latter responsible for the cessation of transit and the resulting rise in gas prices.

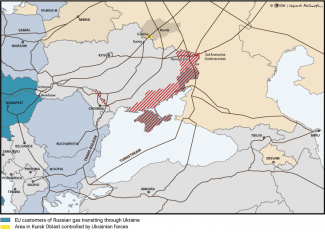

Map. Ukraine’s role on the map of gas export pipelines to the EU

Source: the authors’ own compilation based on entsog.eu and deepstatemap.live.

The future of transit: the scenarios

Given the differing interests of the parties regarding the future of gas transit through Ukrainian territory amidst ongoing hostilities, it is currently difficult to predict with certainty how Ukraine’s gas pipelines will be utilised in the future. However, at least three scenarios are possible.

The first and most likely option is that transit will be completely halted from 1 January 2025, driven by the political determination of both Ukraine and the EU. If this occurs, Russian gas would cease to flow through Ukrainian pipelines, though these could still be repurposed to transport non-Russian gas to Central European markets. A more realistic option in this case would be to use the infrastructure for transporting gas (most likely smaller volumes from Azerbaijan or LNG) supplied via the Trans-Balkan pipeline in reverse, from south to north, from Turkey or Greece. This scenario, however, could increase the risk of Russia launching more frequent and destructive attacks on Ukrainian gas facilities, including those used for domestic supply and gas storage. The likelihood of shipping gas from third countries, such as Azerbaijan, via Russian pipelines to Ukraine and beyond is much lower. This would not only require Moscow’s consent but would also necessitate technical agreements between Russian and Ukrainian operators – an improbable outcome given the ongoing war. The cost risks associated with such an undertaking are also unknown.

Under the second scenario, gas transit would be completely halted this year. Even though shipments of Russian gas through Ukrainian pipelines returned to normal following Ukraine’s occupation of parts of the Kursk Oblast, it is conceivable that Russia could cease transit before the current agreement expires. This scenario is plausible given the unpredictability and intensity of the ongoing military operations around Sudzha, which could result in damage making it impossible to continue gas shipments in the near future. Additionally, Russia might decide to stop transit earlier for political reasons, with Gazprom potentially invoking force majeure.

The third, and most opportunistic, scenario involves finding a new solution for supplying Russian gas through Ukraine to the EU. In the absence of a long-term transit agreement, the simplest approach would be for Russia to sell its gas at the Russian-Ukrainian border. This arrangement would undoubtedly appeal to Russia, and it could also serve as an attractive solution for Austrian and Slovak companies, which still rely on Russian gas.

The consequences for the EU

A complete halt of transit through Ukraine, whether before the end of 2024 or from 1 January 2025, would heighten uncertainty in the EU gas market and likely result in a short-term reduction of available gas volumes, particularly in certain Central European countries. This could prove challenging as winter approaches, when demand peaks, potentially leading to price spikes and increased volatility on commodity exchanges. In addition, it would complicate efforts to supply Ukraine with gas.

However, such price spikes and uncertainties would likely be less severe than those experienced during the first winter after the war began, as countries and market participants have had sufficient time to prepare for the cessation of transit through Ukrainian gas pipelines and to develop strategies for mitigating the worst effects of the resulting crisis. In particular, countries still heavily reliant on Russian supplies would be motivated to accelerate diversification of their energy sources. Phasing out Russian imports would also undoubtedly bring the EU closer to its stated goal of achieving independence from Russian hydrocarbons. Finally, such a move would reduce the risk of Russia using its energy resources as a tool for political leverage in the future.

On the other hand, if Russian gas transit continues (under any terms), the risk of price spikes and uncertainty during the coming winter would diminish. In theory, this scenario could also lower the likelihood of attacks on Ukrainian gas infrastructure, although it is important to note that Russia targeted this infrastructure after the outbreak of full-scale war, despite the ongoing transit of its own gas.

At the same time, continued transit would prolong the EU’s energy dependence on Russia, even as Russia remains engaged in economic conflict with the West. While this might lead to a short-term reduction in gas import costs for the EU, particularly in Central Europe, it would also force member states to continue bearing the long-term political costs of their partial dependence on Russia, including their vulnerability to energy blackmail. Such a situation would weaken the incentive for countries still dependent on Russian resources to phase out these imports and could deepen divisions within the EU. This, in turn, might reduce the chances of reaching consensus on further sanctions, including a potential embargo on Russian gas imports.

APPENDIX

The 2019 Russian-Ukrainian gas agreement

The agreement on the transit of Russian gas through Ukrainian territory was signed on 30 December 2019 for a five-year period. Under this agreement, Gazprom was required to send 65 bcm of gas in the first year and 40 bcm annually in the subsequent years, under a ship-or-pay formula.[7] While Gazprom shipped 41.7 bcm of gas in 2021, after the war broke out and the Ukrainian operator OGTSU ceased accepting gas at the Sokhranivka point (following Ukraine’s loss of control of this border point due to hostilities), Gazprom declined to increase shipments through the Sudzha border point, despite its available capacity. As a result, the transit of Russian gas through Ukraine totalled just 20.5 bcm in 2022 and 14.7 bcm in 2023. Furthermore, Gazprom refused to pay for the transit of the contracted gas in full, leading Ukraine to file a claim with the Paris-based International Court of Arbitration in September 2022; with a ruling expected in 2026.

This reduction in supplies was part of Russia’s policy of curtailing its gas exports to Europe with the aim of exerting political pressure on Brussels, a policy that Moscow started pursing in 2021 and intensified after launching its full-scale invasion of Ukraine. As the strategy failed, there has been an increase in gas sales via Ukraine since late Q4 2023, although the volumes shipped remain below the contracted levels.

The prospects for the transit of Azerbaijani gas through Ukraine

Since June 2024, there have been discussions on the possibility of transporting gas from Azerbaijan through Ukrainian pipelines after the expiration of the Ukrainian-Russian transit agreement. The EU, Ukraine, and Azerbaijan have all expressed non-binding interest in this option. Azerbaijan is interested in both strengthening its energy cooperation with the EU, particularly in the gas sector, and expanding its share in the EU gas market, especially in South-Eastern and Central Europe. The initiative follows a series of EU-Azerbaijani declarations of intent and preliminary agreements, including a 2022 memorandum of understanding with the European Commission, in which Azerbaijan pledged to increase its gas supplies to 20 bcm per year.[8]

At the same time, the concept of Azerbaijani gas transiting through Ukraine to the EU remains rather vague for the time being. Several challenges hinder its implementation in the near future. Azerbaijan currently has limited capacity to significantly increase its production and exports, particularly over the next few years. Additionally, there is uncertainty over the exact route the gas would take to enter the Ukrainian system and reach the EU. Potential options include transit through Turkey and the Trans-Balkan pipeline, through Russia, or via swap deliveries. The costs associated with such an operation are also unclear

[1] D. Krasnolutska, ‘Zelenskiy Says Ukraine Discussing Transit of Azeri Gas to EU’, Bloomberg, 3 July 2024, bloomberg.com.

[2] О. Некращук, Д. Бобрицький, ‘«Ми хочемо експортувати газ». СEO Нафтогазу Олексій Чернишов про справжню ціну палива, переговори із Socar і політичні впливи — інтерв'ю’, NV Бізнес, 6 August 2024, biz.nv.ua.

[3] According to Makogon, Ukraine generates approximately $800 million a year in gas transit fees, yet only $100–200 million is allocated to the state budget – see Н. Топалов, ‘Украина до сих пор качает российский газ и финансирует войну против себя. Продолжится ли это в 2025 году?’, Економічна правда, 15 August 2024, epravda.com.ua.

[4] F. Rudnik, ‘Gazprom in 2023: financial losses hit a record high’, OSW, 14 June 2024, osw.waw.pl.

[5] In 2023, production dropped to a record low of 359 bcm. In contrast to 2021 when Gazprom produced nearly 515 bcm of gas.

[6] ‘Новак: РФ готова поставлять газ по территории Украины и после 2024 года’, ТАСС, 3 July 2024, tass.ru.

[7] See in more detail: S. Kardaś, W. Konończuk, ‘Temporary stabilisation: Russia-Ukraine gas transit deal’, OSW Commentary, no. 317, 31 December 2019, osw.waw.pl.

[8] See: ‘Gaz dla Unii spoza Rosji’, The European Commission – The Representative Office in Poland, 19 July 2022, poland.representation.ec.europa.eu.