China’s pressure on the Philippines: the risk of an escalating conflict

Despite its formal defence alliance with the United States, the Philippines has been grappling with China’s increasing pressure in the South China Sea. The growing number of maritime incidents risks escalating local tensions into a full-scale confrontation between China and the US. China’s claims exceed merely establishing its own exclusive economic zone (EEZ) in the disputed area; it seeks to assert a form of sovereignty akin to that of territorial waters, which are regarded as integral to a nation’s territory. Thus, the South China Sea issue extends beyond a straightforward dispute over the delimitation of the EEZ and challenges fundamental norms of international relations.

Chinese leaders seem to perceive the Philippines as the weakest link in the US alliance network within the Indo-Pacific region. By intensifying their aggressive actions, to which the US has yet to respond effectively, they aim to undermine US security assurances in the view of regional leaders and the general public. The absence of a counter-response to obstruct China’s moves to gain control over much of the South China Sea has strengthened Beijing’s perception of Washington’s limited resolve.

In this respect, China’s policy resembles Russia’s actions towards post-Soviet states before 2022, particularly Ukraine and Georgia. Despite the clear differences between the situations of Ukraine and the Philippines, the lack of a decisive international response and Washington’s stance towards actions below the threshold of war have similarly emboldened China to continue challenging the sovereign rights of other regional nations in the South China Sea. Given the Philippine-US alliance, however, it would be far more challenging for China to initiate an open conflict with the Philippines than it was for Russia to commence its full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

Chinese territorial claims

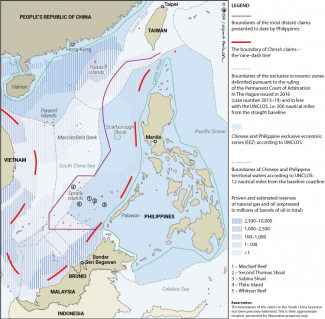

China’s territorial claims,[1] date back to 1947, initially proposed by the government of the Republic of China and later fully upheld by the People’s Republic of China following its establishment in 1949. China essentially seeks to establish territorial waters over approximately 80% of the South China Sea, an area delineated on its initial map of claims by a ‘nine-dash line’. Its claims against the Philippines encompass almost the entirety of the Philippines’ EEZ and, in certain areas, even overlap with its territorial waters (see map).

Since Xi Jinping came to power in 2012, China has intensified its activities in the South China Sea. It has occupied land areas, including reefs, atolls, shoals, and other formations that do not qualify as islands under the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea,[2] and has also constructed artificial islands to host military bases now covering approximately 13 sq km in total. On certain unoccupied atolls, China has installed movable underwater barriers to restrict access to these natural harbours. Around the occupied structures, it has attempted to enforce rights associated with territorial seas and EEZs. The China Coast Guard has prevented other nations’ fishermen and research vessels from accessing the entire disputed area, while units of the so-called Chinese Maritime Militia,[3] have harassed coast guard vessels from other coastal countries. Currently, scarcely a week passes without reports of new incidents, which are growing increasingly severe. Direct encounters, involving tactics such as deploying water cannons and even ramming vessels, are also on the rise. There is genuine concern that it is only a matter of time before these actions lead to casualties.

Securing control over the eastern part of the South China Sea is also vital for China’s efforts to acquire the capability to seize Taiwan by force in the future. The Luzon Strait, which separates the Philippines from Taiwan, could serve as one of the two main supply routes to the island, with the other leading from Japan’s Ishigaki Island. The confluence of political, strategic, and economic factors (such as access to natural resources, see map) indicates that the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) leadership is unlikely to relinquish its territorial claims in the region.

In 1994, China seized Mischief Reef, situated approximately 150 nautical miles from the Philippines, where it constructed an artificial island and declared territorial waters around it. This marked China’s first acquisition at the expense of the Philippines’ EEZ. In 2012, China took control of Scarborough Shoal, located 132 nautical miles from the Philippine Island of Luzon; in September 2024, it seized Sabina Shoal, less than 80 nautical miles from the Philippine coast (see map). The Philippines continues to control the Second Thomas Shoal, where it has grounded an old vessel, the Sierra Madre, though China has consistently sought to obstruct supply and repair operations. The rising frequency and scale of incidents instigated by Chinese vessels suggests that China’s leaders are unwilling to compromise with other coastal nations, instead seeking to intimidate them.

It can be assumed that the CCP leadership perceives its recent actions as successful and is increasingly confident that they are prevailing in this undeclared confrontation, especially as they systematically gain control over more areas in the South China Sea. Simultaneously, they have been relatively explicit in conveying their expectation that the Philippines will loosen its ties with the US.[4] Chinese leaders seem to overlook the inherent contradiction between these two objectives and the reality that this strategy is, in fact, driving the Philippines closer to Washington. It is also plausible that they view intimidation, combined with underscoring the lack of effective US measures to counter Beijing, as a means of neutralising the Philippines.

The CCP has made the objective of ‘reclaiming’ purported Chinese territories a cornerstone of its legitimacy. Thus, abandoning these efforts and recognising the Philippines’ rights to an EEZ under the provisions of UNCLOS is untenable for domestic political reasons. Vague offers of economic cooperation in exchange for the acceptance of Chinese claims are unlikely to alter Manila’s position, as the Philippine public would reject such a concession. Consequently, China’s policy toward the Philippines is an erratic blend of intensifying military pressure, driven by the expectations of both the nationalist Chinese public and elements within the party-state apparatus, alongside vague promises of economic benefits for the Philippines should the Philippines recognise China’s territorial claims.

Manila’s response

Successive Philippine presidents – Benigno Aquino III (2010–2016), Rodrigo Duterte (2016–2022), and Ferdinand Marcos Jr. (since 2022) – have each adopted distinct strategies in response to China’s persistent encroachment on the country’s EEZ in the South China Sea.[5] These approaches have also been indirectly influenced by changes in US support over time. Aquino pursued the path of international law and, in 2014, secured the Enhanced Defense Cooperation Agreement (EDCA) with the US, enabling the return of US forces to the Philippines after a 23-year hiatus. Duterte initially sought a compromise with China, focusing on the joint exploitation of natural resources in the South China Sea. In contrast, Marcos has opted to actively oppose Chinese actions and bolster cooperation with Washington.

Beyond the matter of the Philippines’ territorial integrity (given that Chinese claims partially overlap with the country’s territorial waters), China’s attempts to undermine the Philippines’ sovereign rights to the EEZ, which grants exclusive rights to exploit the area’s mineral and biological resources, strike at the heart of this island nation’s existence. This impacts not only fisheries but also access to energy resources, including gas and oil. The Philippines’ strict adherence to international law in asserting its EEZ claims was also intended to serve as an additional assurance of their international recognition.

In response to China’s seizure of Scarborough Shoal, in 2013 the Philippines brought a case against China to the Permanent Court of Arbitration in The Hague. In 2016, the court upheld most of the Philippines’ claims, determining that China’s ‘historic rights’, if they ever existed, had been nullified by the new regulations established by UNCLOS.[6] However, China refused to participate in the arbitration, contending that the court lacked jurisdiction over the case as it pertained to “sovereignty, not exploitation rights”, which fell outside the court’s purview.[7] Consequently, China disregarded the ruling, despite being a formal party to the Hague Convention, under which the court operates, and having signed and ratified UNCLOS, which provided the legal basis for the court’s decision. In the meantime, China intensified its military pressure on the Philippines across virtually the entire disputed area.

This setback in pursuing international legal remedies spurred the subsequent Philippine president, Rodrigo Duterte, to seek compromise with Xi Jinping, with whom he also established a strong personal rapport.[8] This approach was facilitated by Duterte’s feud with the United States over the Philippines’ human rights record and accusations from the US that he harboured authoritarian inclinations. In retrospect, it appears that the early years of his administration provided China with the best opportunity to draw the Philippines into its sphere of influence. Duterte was likely prepared to go so far as to withdraw from the EDCA and declare a political ‘separation’ from the US.[9]

Duterte was the first Philippine president to select Beijing as the destination for his inaugural foreign trip. During his visit in October 2016, China pledged $24 billion in investments to the Philippines, including significant infrastructural projects under the Belt and Road Initiative. The two sides later discussed joint patrols in disputed waters and a programme to protect fisheries from overexploitation. However, the promises of joint exploitation of resources in the contested areas and large-scale Chinese investments were largely unfulfilled. China initiated only two of the promised infrastructural projects: a bridge and an irrigation system at a single location.

Simultaneously, both China’s and Duterte’s hopes of fostering anti-American sentiment in the Philippines were thwarted. In fact, China’s actions in the South China Sea contributed to a rise in anti-Chinese attitudes among the Philippine public. It appears that Chinese elites, akin to the Kremlin’s approach to Ukraine before 2022, based their expectations on their own projections, largely drawn from Marxist anti-colonial narratives. CCP leaders were convinced that, due to the Philippines’ colonial history, they could easily exploit anti-American sentiment to weaken the Philippine-US alliance. For instance, China interpreted the withdrawal of US forces from the archipelago in 1991,[10] as a US defeat, rather than a result of the normalisation of relations between Manila and Washington.

In 2019 and early 2020, China encircled Thitu Island, which has been under Philippine control since 1971 but is also claimed by China, Taiwan, and Vietnam, deploying hundreds of vessels from the Chinese Maritime Militia to obstruct efforts to upgrade the island’s runway. Beijing subsequently authorised its coast guard to open fire on foreign vessels if necessary; by March 2021, over 200 militia vessels had anchored at the disputed Whitsun Reef. This escalation prompted Duterte to revert to the Philippines’ traditional pro-US foreign and security policy towards the end of his term.[11]

The Philippine-US alliance was fully normalised, and even strengthened, only after Ferdinand Marcos Jr. assumed office in June 2022. In September of that year, during his visit to the United States, the Biden administration pledged to invest $4 billion in the Philippines. The US president also promised to support the Philippines in achieving energy and food security. In February 2023, the two countries signed an annex to the EDCA, granting US forces access to additional Philippine military bases.

In April 2024, President “Bongbong” Marcos and Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida met with Biden at a trilateral summit in Washington, where the three leaders announced plans to develop an agreement aimed at ensuring security and freedom of navigation in the South China Sea. In August 2024, the White House announced an additional $500 million in military aid to bolster the Philippine navy and coast guard. Under the EDCA, the United States has gained access to a total of nine bases in the Philippines; however, these do not host combat units on a permanent or rotational basis, only logistical personnel. The US has also funded the enhancement of military infrastructure in the Philippines, particularly air bases, and allocated $128 million to modernise the Philippine armed forces.

Recently, the Philippine Coast Guard has adopted a policy of publicly releasing video footage from all incidents involving Chinese vessels, aiming to draw international attention to China’s actual actions in the region. Highlighting these incidents, rather than downplaying them as was the case during Duterte’s presidency, has become a tool to apply pressure not only on Beijing but also on Washington. Meanwhile, the Marcos administration has continued to hold talks with China. So far, a familiar pattern has emerged: negotiators reach a new agreement, both capitals publicly present sharply different interpretations, China engages in another provocation, and the negotiations revert to square one, allowing Beijing to advance by seizing additional areas.

The global context

The Philippines, a former US dependency and de facto colony, has been one of America’s oldest allies since gaining full independence in 1946. The 1951 Mutual Defense Treaty between the United States and the Republic of the Philippines obliges both parties to support each other in the event of an attack by another state against their territory, armed forces, or civilian ships and aircraft in the Pacific region.[12] Other regional countries regard the Philippines as a measure of Washington’s influence in the Indo-Pacific. For China, severing these ties would constitute a major political and strategic success. Nevertheless, China’s policy towards the Philippines remains inextricably linked to the South China Sea issue and its territorial claims based on the ‘nine-dash line’.[13]

China’s offensive operations in the South China Sea are part of a broader pattern of its actions on the international stage, such as those that have heightened tensions with India and Japan – actions which Indo-Pacific countries perceive as attempts to assert regional dominance. In response, these nations have pursued bilateral security cooperation with the US and strengthened regional collaboration, including with the Philippines. In May 2024, the United States, Australia, Japan, and the Philippines officially confirmed the formation of a group known as the ‘Squad’; the four countries have been conducting joint maritime patrols in the Philippines’ EEZ. Before that, two informal alliances were also formed: India, Australia, Japan, and the US launched the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (QUAD) in 2007, while Australia, the United Kingdom, and the US announced the AUKUS partnership in 2021. A group of Pacific nations consisting of Australia, Japan, South Korea, and New Zealand, informally known as AP4, has formed a partnership with NATO.[14]

The United States remains a common and indispensable element in all these initiatives. Despite renewing its network of alliances in the region, the US appears unable to prevent China’s advances that remain below the threshold of war, though it has taken several steps to reinforce its bilateral defence agreements with the Philippines. While recognising the significant differences between operations on land and at sea, as well as the differing state of military alliances in East Asia and Eastern Europe, this situation mirrors the predicament of Ukraine after Russia’s 2014 annexation of Crimea but before its full-scale invasion. Successive US administrations have adhered to the approach towards East Asia established by President Barack Obama (2008–2016),[15] which underscores the inviolability of Philippine sovereignty and commits the US to defend the Philippines in accordance with treaty obligations. Conversely, Washington has been reluctant to mediate between the parties and hesitant to respond directly to China’s provocations as long as these remain short of outright aggression. The Obama administration exhibited considerable naivety towards both Russia (via its reset policy) and China, with President Obama trusting Xi Jinping’s assurances in 2015 that China would refrain from militarising the artificial islands it was constructing in the South China Sea. Nevertheless, by 2022, China had militarised seven of these islands.

The steps taken by the US to increase its military presence in the Philippines and promote regional military cooperation have thus far failed to halt China’s advances in the region. Beijing has found ample scope for a range of actions below the threshold of war that continue to undermine Philippine sovereignty and gradually expand China’s de facto territorial waters and EEZ at the expense of other countries. This largely stems from Washington’s reluctance to inflame the situation and its desire to quickly defuse any emerging flashpoints. The US is wary of being seen as the party escalating the tensions – both by the ASEAN countries and its allies, both within and beyond the region. Another important factor is the American public’s reluctance to see the US engaged in another armed conflict, especially after those in Iraq and Afghanistan. As a result, China has gained more room to expand its presence across the South China Sea, a situation that the CCP leadership interprets as a sign of Washington’s weakness and lack of resolve.

Conclusions

Amid intensifying competition with China, the loss of the Philippines as an ally would represent the most severe setback to the United States’ dominant role in the region since World War II. Given that China’s territorial claims in the South China Sea have become a significant factor in US-China rivalry are of critical importance to both the Philippines and China, a peaceful resolution of the dispute appears unlikely in the foreseeable future. Thus, tensions in the region are likely to escalate further.

While both sides currently appear committed to keeping tensions below the threshold of war, there is a genuine risk that events could spiral out of control. The Philippines remains a treaty ally of the United States and continues to host US forces on its territory.[16] Consequently, it would be significantly more challenging for China to initiate open conflict against the Philippines than it was for Russia to launch its full-scale invasion of Ukraine. Such a move would likely trigger conflict with the US and its allies, as Washington has successfully revitalised its alliance network in the region.

This raises questions about whether past experiences, particularly the lack of serious consequences following China’s blatant violations of international law and its disregard for the Hague-based Permanent Court of Arbitration’s ruling, could lead to a further escalation of the dispute. The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) leaders’ decisions are increasingly driven by an ideology blending Marxism and nationalism, which asserts that a clash with the West is inevitable and that its decline is certain. Similar to the Kremlin’s actions in recent decades, this could reinforce China’s belief that, in the long run, the United States will be unable to uphold the security status quo in Asia. Consequently, Beijing may feel emboldened to take more far-reaching steps than those it has pursued recently.

The future developments and eventual outcome of the Russia-Ukraine war are also significant factors. It can be assumed that Ukraine’s example serves as a deterrent to Xi Jinping and his circle. However, the fact that the armed conflict is now in its third year, yet Russia has not faced a full mobilisation of Western countries, has reinforced Beijing’s deeply rooted belief that the West may lack the resolve for a prolonged struggle. From China’s perspective, the absence of robust resistance to its actions in the South China Sea further validates this notion.

China’s advances in expanding its control over the South China Sea have clearly bolstered its confidence, while also encouraging it to deepen the de facto Chinese-Russian alliance.[17] These ties are evolving strategically from a purely defensive relationship – where authoritarian regimes feel threatened by Western democracies and believe that they seek to overthrow them – into a revisionist alliance that aims to actively reshape the global order. It appears that the Chinese leadership’s calculations are partly based on the belief that, in the long run, after China secures new territorial gains in the South China Sea, the credibility of US security guarantees will erode – not only in the Indo-Pacific but also globally. This is likely to embolden other revisionist states in the region, such as Iran and North Korea, to take more assertive actions. For China, spreading US forces thin is a key objective, as this would further weaken Washington’s resolve to defend both the Philippines and Taiwan.

Map. Chinese and Philippine claims in the eastern regions of the South China Sea

Sources: Marine Regions, 21 October 2024, marineregions.org; M. Hossain, M. Hashim, ‘Earth observatory data for Maritime Silk Road development in South East Asia’, Jurnal Teknologi, no. 79 (6), August 2017; Zou Keyuan, ‘Scarborough Reef: A new flashpoint in Sino-Philippine relations?’, IBRU Boundary and Security Bulletin, summer 1999; ‘China has militarised the South China Sea and got away with it’, The Economist, 21 June 2018, economist.com; ‘See U in court’, The Economist, 18 July 2015, economist.com; Contested areas of South China Sea likely have few conventional oil and gas resources, U.S. Energy Information Administration, 3 March 2013, eia.gov.

[1] For more on China’s claims and the legal aspects of disputes in the South China Sea, see M. Bogusz, Nine dashes. Beijing’s territorial claims in the South China Sea, OSW, Warsaw 2020, osw.waw.pl.

[2] The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) defines an island as “a naturally formed area of land, surrounded by water, which is above water at high tide”. However, rocks and other formations that “cannot sustain human habitation or economic life of their own shall have no exclusive economic zone or continental shelf”. See United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, United Nations, un.org.

[3] The term ‘Chinese Maritime Militia’ is commonly used to describe Chinese fishing vessels that have been reinforced with steel hull plating and equipped with other ‘non-standard’ equipment, such as anti-boarding barbed wire. These boats are mobilised in large numbers and, with the assistance of the Chinese coast guard, used for aggressive actions. Vessels of the ‘Chinese Maritime Militia’ have repeatedly blocked or even rammed ships from other countries attempting to patrol disputed waters claimed by China.

[4] See Zhang Han, ‘Wang Yi warns of ‘small cliques’ amid US-orchestrated South China Sea tension’, Global Times, 18 April 2024, globaltimes.cn; ‘Chinese FM warns Philippines over U.S. intermediate missile system deployment’, Xinhua, 27 July 2024, english.news.cn; ‘Wang Yi Has a Phone Call with Philippine Secretary of the Department of Foreign Affairs Enrique A. Manalo’, Embassy of the People’s Republic of China in Eritrea, 20 December 2023, er.china-embassy.gov.cn; ‘Wang Yi Meets with Philippine Foreign Secretary Luis Enrique Manalo’, Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China, 6 July 2023, mfa.gov.cn.

[5] The Philippines established its 200-nautical-mile Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) as early as 1978. A 2012 declaration further defined its claims to the continental shelf beyond the EEZ boundary. In June 2024, the Philippines submitted a claim for an extended continental shelf reaching up to 350 nautical miles west of Palawan Island.

[6] ‘The South China Sea Arbitration (The Republic of the Philippines v. the People’s Republic of China)’, The Permanent Court of Arbitration, 12 July 2016, at: web.archive.org.

[7] See M. Bogusz, Nine dashes…, op. cit., p. 13.

[8] See R. Cruz de Castro, ‘The Duterte Administration’s appeasement policy on China and the crisis in the Philippine–US alliance’, Philippine Political Science Journal, Vol. 38, 2017, Issue 3, pp. 159–181, at: tandfonline.com.

[9] B. Blanchard, ‘Duterte aligns Philippines with China, says U.S. has lost’, Reuters, 20 October 2016, reuters.com.

[10] Except for the period of Japanese occupation during World War II, US forces have been stationed continuously in the Philippines since the 1898 Spanish-American War.

[11] See D. Grossman, ‘Duterte’s Dalliance with China Is Over’, RAND, 2 November 2021, rand.org.

[12] See ‘Mutual Defense Treaty Between the United States and the Republic of the Philippines’, U.S. Department of State, 2 August 1951, history.state.gov.

[13] E. Wong, ‘China Hedges Over Whether South China Sea Is a ‘Core Interest’ Worth War’, The New York Times, 30 March 2011, nytimes.com.

[14] ‘Relations with partners in the Indo-Pacific region’, NATO, 16 July 2024, nato.int.

[15] See M. Landler, ‘Obama Expresses Support for Philippines in China Rift’, The New York Times, 8 June 2012, nytimes.com; E. Rauhala, ‘Obama in the Philippines: ‘Our Goal Is Not to Contain China’’, Time, 28 April 2014, time.com; M. Spetalnick, R. Francisco, ‘Obama puts South China Sea dispute on agenda as summitry begins’, Reuters, 17 November 2015, reuters.com.

[16] Under the Philippine Constitution, foreign troops may only be stationed in the archipelago on a rotational basis. As a result, the number of US personnel varies significantly depending on ongoing activities, ranging from a few hundred to several thousand.

[17] See M. Bogusz, J. Jakóbowski, W. Rodkiewicz, The Beijing-Moscow axis. The foundations of an asymmetric alliance, OSW, Warsaw 2021, osw.waw.pl.