The resilience of the European Union and NATO in an era of multiple crises

NATO and the EU, Europe’s two most important security institutions, are currently pursuing their second round of efforts within the past decade to enhance the crisis resilience of states and societies. The first followed Russia’s annexation of Crimea, prompting both organisations to strengthen their situational awareness, cybersecurity, and counter-disinformation efforts. A key milestone was reached in 2016 with NATO’s adoption of seven baseline requirements for civil preparedness. The present series of measures was triggered by the COVID-19 pandemic and Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine. Lessons from this succession of crises relate to strategic reserves, healthcare system capacity, supply security, civilian protection and evacuation, as well as countering sabotage operations.

The European Commission’s (EC) proposals aim to comprehensively enhance the EU’s crisis resilience outside the area of NATO’s collective defence. One reflection of these ambitions is a report on strengthening Europe’s civil-military preparedness, which was drafted under the guidance of former Finnish President Sauli Niinistö and presented by the EC in October 2024. Two months later, NATO announced plans to update its strategy for countering hybrid threats. Both organisations should continue to coordinate their efforts as closely as possible to maximise synergies while avoiding unnecessary duplication of structures and competition.

Comprehensive security according to the EU

For over a decade, the EU has been developing mechanisms to enhance the resilience of its member states across various sectors. Between 2008 and 2022, it implemented the European Programme for Critical Infrastructure Protection (EPCIP), which focused on the energy and transport sectors. With the adoption of the Critical Entities Resilience Directive (CER),[1] in 2022, its scope was expanded to include banking, financial market infrastructure, healthcare, drinking water, wastewater, digital infrastructure, public administration, space, and the production, processing and distribution of food. The directive introduced harmonised minimum standards designed to ensure the continuity of essential services and enhance the resilience of critical entities – those providing services in the specified sectors. Failure to comply with these obligations may result in financial sanctions imposed by the EU’s member states. At the same time, for security reasons, critical entities may receive state support, which will not be considered unlawful state aid. Moreover, since 2001, the Union Civil Protection Mechanism has been in operation and continuously developed, coordinating emergency and humanitarian assistance in response to natural disasters.

Since 2014, the EU has been working to develop its capabilities to counter hybrid threats in areas such as combating weapons of mass destruction, ensuring energy security, maritime security, data protection, border security, space, and foreign direct investments. Enhancing situational awareness, cybersecurity, and countering disinformation have become increasingly important in strengthening the EU’s resilience. In 2019, the EU Council acknowledged “the possibility for the Member States to invoke the Solidarity Clause (Article 222 TFEU) in addressing a severe crisis resulting from hybrid activity”. The 2022 Strategic Compass set a new level of ambition in this area. Under this framework, the EU’s member states have been developing hybrid response tools (the EU Hybrid Toolbox), including the EU Hybrid Rapid Response Teams, established in 2024, which resemble NATO’s counter-hybrid teams.

On 30 October 2024, the EC published a report entitled ‘Safer Together: Strengthening Europe’s Civilian and Military Preparedness and Readiness’[2], drafted under the leadership of former Finnish President Sauli Niinistö. The report was commissioned jointly by the EC’s President Ursula von der Leyen and High Representative of the EU for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, Josep Borrell. With this initiative, the EC and the European External Action Service (EEAS) aim to ‘map out’ the EU’s competencies in the broad area of security policy and external relations. The document includes recommendations in eight critical areas (see Appendix).

The Commission’s primary objective is to utilise existing tools and instruments more effectively while avoiding treaty changes, which would be controversial for some member states. Efforts to enhance the EU’s crisis response capabilities would focus on expanding the Emergency Response Coordination Centre (ERCC), which has operated within the Commission since 2013, and improving the Integrated Political Crisis Response (IPCR) mechanism under the EU Council. The ERCC would act as a central operational hub, a ‘one-stop shop’ for crisis response. Over time, it would also gradually assume a leading role from the EU Council in a shift euphemistically described as ‘strengthening links with crisis management structures within the EEAS’.

The Niinistö report calls for the ‘further operationalisation’ of Article 42(7) of the Treaty on European Union (TEU) (the mutual defence clause) and Article 222 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU) (the solidarity clause). The former establishes an ‘obligation of aid and assistance by all means in their power’ on member states that fall victim to armed aggression. However, there is no consensus among EU member states on interpreting it in a manner akin to Article 5 of the Washington Treaty. As a result, the report’s recommendations regarding this provision remain broad, focusing on developing activation scenarios and defining the EU’s role in providing assistance in the event of aggression. Regarding Article 222 TFEU, the report suggests lowering the ‘threshold’ for its activation (currently, a member state must demonstrate that its own resources are insufficient to handle a crisis) and broadening its scope to cover hybrid actions, sabotage, cyberattacks, and pandemics.

The report recommends establishing the Defending Europe Facility and the Securing Europe Facility as separate budgetary instruments to consolidate all EU investments in support for the defence industry and civil protection/crisis response, respectively. This recommendation aligns with the EC’s proposal to centralise all dedicated funding in these two areas. Ahead of the forthcoming negotiations on the Multiannual Financial Framework (MFF) for 2028–34, the report calls for integrating the ‘crisis preparedness’ factor into the design of the EU budget, along with greater flexibility in both the MFF and annual budgets. This aims to enable the Commission to manage resources more freely and strengthen its role as a provider of financial support.

NATO’s role in countering hybrid threats

NATO adopted its first strategy for countering hybrid threats in 2015 in response to Russia’s annexation of Crimea. Although the document remains classified, the Alliance has stated that its core pillars include enhancing preparedness to counter hybrid threats (primarily from Russia and China) as well as deterrence and defence against such threats.[3] The organisation’s key priorities in this area include collecting, analysing and sharing information, supporting member states in identifying vulnerabilities and strengthening resilience; and providing expertise on civil preparedness, countering weapons of mass destruction, crisis response, critical infrastructure protection, strategic communications, civil protection, energy security, and counterterrorism. Since the 2016 Warsaw Summit, NATO has also recognised that a hybrid attack, like a cyberattack, could trigger Article 5. In 2017, a Hybrid Analysis Branch was established at NATO Headquarters within the newly created Joint Intelligence and Security Division (JISD). Since 2018, the Alliance has maintained counter-hybrid support teams, which provide advisory assistance to member states upon request. In 2019, Montenegro activated this mechanism to help secure its parliamentary elections; in 2021, Lithuania utilised it following the outbreak of the migrant crisis at its border with Belarus. Amid escalating hostile irregular activities, NATO countries announced at a meeting of their foreign ministers in December 2024 they had begun work on updating the Alliance’s existing strategy for countering hybrid threats. However, no details of the proposed revisions have yet been disclosed.

In recent years, the protection of critical undersea infrastructure has become a key focus of NATO’s efforts to counter hybrid threats. This follows the damage to the Nord Stream 1 and 2 gas pipelines (2022), the Balticconnector pipeline (2023), the Estlink2 power cable (2024), and several telecommunications cables. In response, in 2024, NATO established its Maritime Centre for the Security of Critical Undersea Infrastructure within the Allied Maritime Command (MARCOM) and Critical Undersea Infrastructure Network. In January 2025, the Supreme Allied Commander Europe (SACEUR) ordered an increase in allied air, surface, and underwater vigilance activities in the Baltic Sea, to protect critical undersea infrastructure and deter further incidents.[4] These measures demonstrate NATO’s ability to respond swiftly to emerging threats.

NATO’s approach to hybrid threats partially overlaps with its broader efforts to strengthen the overall resilience of states and societies against aggression. This pertains to the seven baseline requirements for NATO’s civil preparedness, adopted at the 2016 Warsaw Summit. These include: the continuity of government and critical government services, resilient energy supplies, the ability to manage uncontrolled population movements; resilient food and water resources; the capacity to handle mass casualties; and resilient civil communications and transportation systems. In 2017, NATO adopted assessment criteria for implementing these requirements, followed by the issuance of relevant guidelines for member states in 2018. In 2021, the member states committed to further strengthening their resilience against conventional, irregular, hybrid, terrorist, cyber, and information threats (Strengthened Resilience Commitment). In 2023, NATO approved resilience objectives to guide the development of civilian capabilities. The declaration of the 2024 NATO Summit in Washington went a step further, explicitly stating that civilian planning would be integrated into national and collective defence planning in times of peace, crisis, and conflict. In practice, NATO’s efforts in this domain have long been relatively limited. However, training and exercises, including the incorporation of hybrid scenarios and collaboration with the private sector in NATO’s live exercises, play a significant role.

At the same time, the importance of cyber defence within NATO continues to grow. The Alliance encourages member states to increase investment in cybersecurity, facilitates information sharing and training, protects its own networks, and supports national security efforts. In 2023, it adopted a new framework for enhancing the role of cyber defence in NATO's overall deterrence and defence posture. The Alliance has now launched a process of consolidating its dispersed cyber capabilities. As part of this effort, NATO announced the establishment of the Integrated Cyber Defence Centre.[5]

In October 2024, NATO member states also formulated a common approach to countering information threats. This initiative aims to facilitate early warning of hostile information operations, enhance response mechanisms (including through proactive strategic communications), and strengthen efforts to deter and mitigate such threats through joint statements, corrections and measures to counter hostile narratives, and publicly attribute responsibility. NATO’s Committee on Public Diplomacy will play a leading role in coordinating these efforts.

Strengthening the EU’s resilience: opportunities, challenges, and prospects

The Niinistö report builds on previous key documents, including the Strategic Compass, the Versailles Declaration, the European Defence Industrial Strategy (EDIS) and the European Commission President’s political guidelines for 2024–29. Therefore, it can be seen as part of a broader ‘roadmap’ for developing a European Defence Union’, understood as a synergy between the European Commission’s security initiatives and the Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP), coordinated by the EU Council. At the same time, the report is intended to guide work on future documents, such as the EU Strategy for a Preparedness Union and the White Paper on the Future of European Defence.[6] It also reflects the EU institutions’ broader political strategy, which seeks to secure new competences and additional funding from member states to enhance (in their view) the organisation’s ability to conduct security policy and manage relations with external partners and competitors.

The report could also drive further legislative and regulatory initiatives to set minimum EU-wide compliance standards for preparedness in areas such as education, stockpiling reserves, construction (including shelter design), energy security, and public procurement. Implementing recommendations to introduce EU-wide regulations on standards and requirements in the field of crisis preparedness, including binding obligations on member states, would represent a breakthrough. Similarly, expanding the framework for protecting critical infrastructure to include the defence industry would impose new responsibilities and costs on businesses.

The EU’s legislative efforts to enhance preparedness for threats across its member states would spark internal debate and align with Poland’s plans to invest in civil protection and civil defence systems. At the same time, the Niinistö report highlights the importance of military mobility, a key issue for the security of NATO’s eastern flank. It also outlines prospects for allocating additional funds to costly initiatives, such as replenishing strategic reserves. For Poland’s presidency of the EU Council, the report offers further justification for advocating policies aligned with national interests.

Even partial implementation of the report presents an opportunity to secure additional EU support for external border protection. A shift in the European Commission’s stance on this issue is reflected in its statement of 11 December,[7] which acknowledged the member states’ right to invoke Treaty provisions to restrict asylum rights in cases of deliberately induced migration. The statement also announced further assistance in securing the EU’s external borders.

Implementing the report’s recommendations could encounter significant resistance. Some capitals may question the necessity for further expanding crisis response structures within the European External Action Service and the European Commission. This could also complicate ongoing cooperation between the EU and NATO. Even if the concept of a ‘fully-fledged EU intelligence cooperation service’ remains a long-term ambition for Brussels, some member states may oppose deeper collaboration in this area within the EU, primarily due to the risks associated with sharing sensitive information in an environment vulnerable to infiltration by hostile intelligence services, both within EU institutions and among certain member states.

Regarding threat assessment, the European Commission largely confines itself to agreeing on a comprehensive list of threats, but the real challenge lies in reaching a common understanding of their urgency and prioritisation. Some countries may argue that attributing hybrid attacks (or, even more so, taking retaliatory action) should not take place at the EU level. Additionally, any recommendations from the report that entail additional costs could face resistance from the so-called ‘frugal’ member states. The proposal to link the distribution of certain EU funds to the fulfilment of crisis preparedness tasks may also be perceived as another means of expanding the European Commission’s discretionary decision-making power.

The risks associated with implementing the report reflect broader concerns about transferring additional competences to EU institutions and encouraging measures that centralise security policy at the expense of member states and the responsibilities of other organisations, particularly NATO. There is also a risk that EU-imposed security standards could be enforced without taking into account the specific security concerns of individual countries. Another potential issue is that the European Commission could define the scope of future regulations too ambitiously, without a clear guarantee of securing funding for their implementation.

Notably, the report emphasises the need for closer EU-NATO cooperation and avoids divisive debates on European strategic autonomy. It also adopts a measured approach to defining EU-US cooperation. It identifies Russia as the primary threat, aligning with NATO’s threat assessment. Some of its proposals mirror NATO’s existing solutions, such as the adoption of Preparedness Baseline Requirements, modelled on NATO’s seven baseline requirements for civil preparedness.[8] Enhancing non-military crisis resilience in states and societies offers a promising avenue for EU-NATO cooperation, particularly in relation to strategic reserves. Strengthening the European Commission’s role could improve communication between the two organisations on key security issues.

The report’s sections on broadly defined logistical support from the EU are relevant to collective defence and NATO’s regional defence plans. This support includes enhancing military mobility, protecting critical infrastructure, fostering partnerships with the private sector, and strengthening strategic reserves. Implementing the report’s recommendations on investment in the defence industry and support for employment in the security sector would help build the forces required to fulfil these plans.

Enhancing NATO’s resilience and its correlation with the EU

The adoption of NATO’s 2022 Strategic Concept did not represent a breakthrough in the Alliance’s approach to resilience, as it was not recognised as a fourth core task alongside deterrence and defence, crisis prevention and management, and cooperative security. Extensive discussions also failed to expand the seven baseline resilience requirements (for instance, by adding payment systems, psychological defence or software security) or to transform NATO’s Euro-Atlantic Disaster Response Coordination Centre into an allied material reserves agency, a concept that gained traction during pandemic response efforts. In principle, NATO’s Resilience Committee aims to encourage member states to plan, implement, and report on their civilian capabilities. However, capitals have been granted considerable discretion in this regard. There is no advanced mechanism comparable to the NATO Defence Planning Process (NDPP), nor is there a control mechanism. Several factors hinder cooperation on baseline resilience requirements: the governments’ reluctance to share information regarding sensitive aspects of national security systems; significant disparities in how countries manage strategic reserves and civil defence; and budgetary constraints, as spending on broadly defined resilience is ‘parked’ across a number of ministries. Rebuilding non-military resilience against aggression in Europe will be a laborious process, as post-Cold War cutbacks and privatisation have deprived many NATO members of the previously available tools.

Within NATO, the primary responsibility for responding to hybrid attacks lies with individual member states, and the effectiveness of such responses depends largely on their own capabilities. The Alliance plays a supporting role. In addition, activating certain response measures requires approval from the North Atlantic Council, which may delay assistance. For instance, the deployment of a NATO counter-hybrid team to Lithuania in 2021 required such authorisation. At the same time, in recent years, SACEUR has been granted greater freedom to increase the activity of allied forces, such as Baltic Sentry, and to deploy the Allied Reaction Force. These changes have enhanced deterrence against large-scale hybrid aggression.

Hybrid and terrorist threats, along with resilience, became the primary areas of closer EU-NATO cooperation as early as 2016–2017. Regular information exchanges take place between various EU and NATO bodies, in addition to collaboration through the European Centre of Excellence for Countering Hybrid Threats in Helsinki. Since 2022, the two sides have engaged in structured dialogue on resilience, which was expanded to include cybersecurity in 2024; both initiatives aim to better align their efforts. In January 2023, a Joint Task Force on the Resilience of Critical Infrastructure was established, providing recommendations on protecting energy, transport, digital, and space infrastructure. The structures of both organisations have cooperated in this area with relative ease. Unlike NATO, the EU has the authority to impose sanctions on states and entities engaging in harmful hybrid activities. However, as a military alliance, NATO can decide to launch preventive military operations, for example, in response to threats to maritime infrastructure or at the border between an allied state and a hostile country; it can also deploy advisory teams.

NATO’s updated hybrid strategy should address emerging threats, with particular focus on protecting critical undersea infrastructure. This includes developing response protocols for incidents occurring beyond territorial waters, including maritime areas without full jurisdiction of coastal states. Another key issue is countering Russian GPS jamming, for example, through investments in inertial navigation systems. The new strategy could also encourage member states to invest in their internal security agencies and incorporate AI-driven threat detection tools, alongside increased spending on surveillance of the North Atlantic Treaty area, such as satellite and unmanned systems. At the same time, NATO’s stated ambitions to play a greater role in countering disinformation are likely to face significant obstacles. The Alliance should instead focus on its own strategic communications. The updated strategy could also be complemented by the Layered Resilience Concept, which is currently being developed by NATO’s Allied Command Transformation (ACT). This framework envisions the mutual integration and reinforcement of civil and military preparedness.[9]

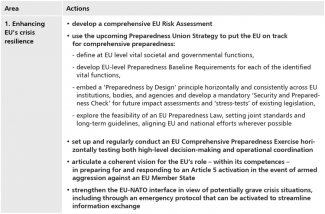

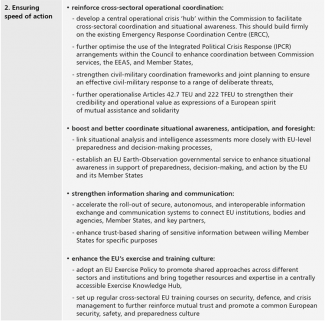

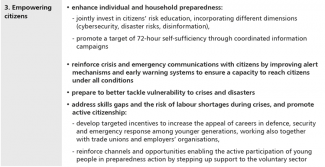

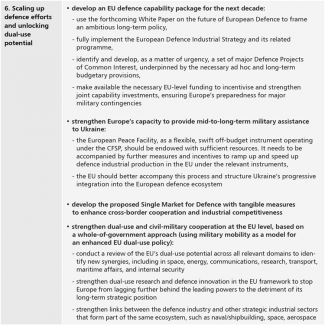

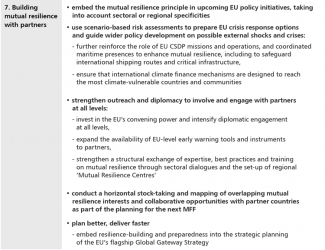

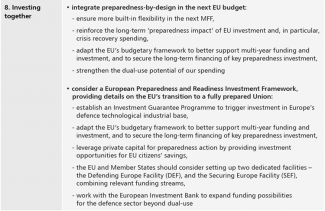

Appendix. Selected proposals from the Niinistö report

[1] Directive (EU) 2022/2557 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 14 December 2022 on the resilience of critical entities and repealing Council Directive 2008/114/EC (Text with EEA relevance), eur-lex.europa.eu.

[2] S. Niinistö, Safer Together – Strengthening Europe’s Civilian and Military Preparedness and Readiness, The European Commission, 30 October 2024, commission.europa.eu.

[3] E.H. Christie, K. Berzina, ‘NATO and Societal Resilience: All Hands on Deck in an Age of War’, German Marshall Fund, 20 July 2022, gmfus.org; A. Dowd, C. Cook, ‘Bolstering Collective Resilience in Europe’, Center for Strategic & International Studies, 9 December 2022, csis.org; ‘Countering hybrid threats’, NATO, 7 May 2024, nato.int.

[4] P. Szymański, ‘Baltic Sentry: NATO’s enhanced activity in the Baltic Sea’, OSW, 15 January 2025, osw.waw.pl.

[5] NATO’s Cyber Security Centre is responsible for protecting the Alliance’s networks and can also deploy rapid response teams to assist a member state under cyberattack. In 2018, the Cyber Operations Centre was established at SHAPE, tasked with building shared situational awareness, coordinating allied activities, and securing NATO operations. Cyber response capabilities were further strengthened in 2022, when the Allies decided to establish the Virtual Cyber Incident Support Capability. This initiative provides voluntary cyber assistance, enabling member states to support one another upon request.

[6] ‘White paper on the future of European defence’, The European Parliament, 5 November 2024, europarl.europa.eu.

[7] ‘Communication on countering hybrid threats from the weaponisation of migration and strengthening security at the EU’s external borders’, The European Commission, 11 December 2024, eur-lex.europa.eu.

[8] W.-D. Roepke, H. Thankey, ‘Resilience: the first line of defence’, NATO Review, 27 February 2019, nato.int.

[9] NATO Warfighting Capstone Concept, Allied Command Transformation, 2021, act.nato.int; ‘The Layered Resilience Concept’, CIMIC Handbook, 20 August 2024, handbook.cimic-coe.org.