A disappearing country. Moldova on the verge of a demographic catastrophe

Moldova is one of the fastest depopulating countries in the world. Since it gained independence in 1991, the population of its right-bank region (the territory controlled by Chișinău, excluding the separatist region of Transnistria) has shrunk by approximately 35%. This is primarily due to mass labour migration driven by economic conditions, involving over one million citizens of a country with a current population of 2.4 million. Other significant factors contributing to Moldova’s declining population include a dramatic drop in fertility rates and high mortality associated with low life expectancy, which is ten years below the EU average. Consequently, Moldovan society is ageing rapidly; in 1991, the average age of a resident was 29, compared to 38 at present.

The catastrophic population decline and the resulting difficulty in finding workers pose a serious challenge for the state and its economy, with an ageing society placing increasing strain on the budget. Within the next few years, the number of retirees is likely to match the number of employed individuals, potentially causing the collapse of the already inefficient pension system. Furthermore, there is no indication that Moldova’s demographic situation could improve in the foreseeable future.

The evolution of the demographic situation

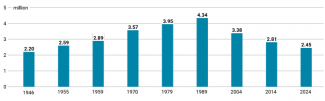

The population of the Moldavian Soviet Socialist Republic (MSSR) grew steadily from the late 1940s, driven by the post-World War II baby boom. While the republic’s population in 1959 was 2.86 million, the 1970 census recorded 3.57 million residents (a 25% increase), rising to 3.95 million by 1979. Ten years later, just before the collapse of the USSR, this figure reached 4.34 million.

The rapid population growth in the MSSR was due to both high birth rates (with 3.3 children per woman in 1960 and an average of 2.5 during the 1970s) and significant migration from other regions of the Soviet Union. This influx, primarily from the Russian, Ukrainian, and Belarusian SSRs, was largely attributed to the intense industrialisation process within the republic.

Chart 1. Moldova’s population from 1946 to 2024

Source: estimates, data from the Russian Higher School of Economics and the censuses conducted in the USSR and the independent Republic of Moldova.

The trend of population growth reversed immediately after the collapse of the USSR. In 1992, following the Transnistrian War and the effective secession of this separatist region, which had a population of approximately 700,000, the newly established Moldovan state had about 3.7 million residents. By 2004, this figure had fallen to 3.38 million, dropping further to just 2.8 million a decade later and approximately 2.4 million by 2024. The sharp depopulation affected virtually the entire country, with the exception of the Chișinău municipal region (essentially the capital’s metropolitan area). According to available data, this region has maintained a population similar to or even slightly higher than its 1989 level of 650,000–700,000 residents.[1]

Causes of the demographic crisis: low fertility…

The dramatic population decline in Moldova is driven by natural factors and mass labour migration, primarily influenced by economic conditions. Over the past 30 years, birth rates have fallen significantly. While the fertility rate was 2.5 in 1989, it had dropped to just 1.24 by 2013. Although it has slightly increased in recent years – reaching around 1.6 in 2023 (compared to the EU average of 1.46 in 2022) – it remains significantly below the replacement level of 2.1–2.2.

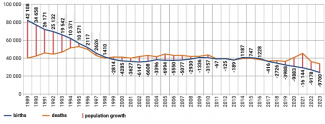

At the dawn of Moldova’s independence, births outnumbered deaths almost two-to-one (72,000 to 45,000). However, in the following years, birth rates began to decline sharply. Since 1999, annual deaths have consistently exceeded births (see chart 2). By 2023, the number of newborns had declined by 70% compared to 1989.

Chart 2. Number of births and deaths from 1989 to 2023

Source: National Bureau of Statistics of the Republic of Moldova.

Life expectancy in Moldova remains relatively low. In 2023, it was just 71.9 years for both sexes, compared to the EU average of 81.5 years and 79.27 years in Poland. Since 1989, when life expectancy stood at 69 years, it has risen by less than three years (see chart 3).

Chart 3. Dynamics of life expectancy in Moldova and in Poland from 1989 to 2023

…and mass migration

Moldova’s demographic challenges are further exacerbated due to mass labour migration. This phenomenon intensified in the late 1990s because of a sharp economic downturn. The collapse of the USSR severely impacted Moldova’s economy, which was heavily reliant on the Soviet market and non-competitive beyond it. The secession of the highly industrialised Transnistria region, which had accounted for 40% of the Moldavian Soviet Socialist Republic’s GDP, 33% of its industrial output, and 90% of its energy production, further compounded the crisis. These two factors led to a 35% drop in the GDP of the newly established independent state between 1990 and 1992. Although Moldova’s political situation stabilised in the following years, as it adopted a constitution in 1994 and managed to resolve the Gagauz separatism issue[2]), the economy continued to shrink until the early 2000s. Additional setbacks came from the Russian financial crisis of 1998, which caused Moldova’s GDP to plummet by 15%, reducing it in 1999 to just 33% of its 1990 level.

Since the early 21st century, Moldova’s economy has experienced growth, despite recurring crises such as the 2008 financial collapse and the 2014 embezzlement of approximately $1 billion from three Moldovan banks by corrupt political and business elites.[3] Nevertheless, the country has not yet recovered fully from the economic losses it sustained during the first decade of its independence. As of 2023, Moldova remains one of the poorest nations in Europe, alongside Kosovo and war-torn Ukraine, with a GDP per capita of $6,651.[4]

Significantly lower wages in Moldova compared not only to the EU but also to Russia and Belarus have forced 1–1.2 million citizens – 40–50% of the country’s current population – to leave over the past 30 years in search of work.[5] The majority of this diaspora now resides in the European Union. Precise numbers are difficult to determine, as Chișinău does not maintain detailed statistics, and a significant proportion of Moldovans in the EU hold Romanian passports (discussed further below). Estimates suggest that the largest Moldovan communities are in Italy (approximately 300,000), France (100,000–160,000), and Germany (around 100,000). The United Kingdom is home to approximately 50,000 Moldovan nationals. Additionally, a large number have emigrated to Israel (primarily for short-term work as caregivers and construction workers), the United States, Turkey (mainly residents from the southern region of Gagauzia), and the United Arab Emirates. Until 2014, Russia was the primary destination for Moldovans seeking employment, with around 600,000 living there at the time. However, this trend has sharply declined over the past decade, with the current number falling below 80,000.[6] Moldovan expatriate workers have lost interest in the Russian labour market for several reasons, including the depreciation of the rouble since 2014, stricter Russian migration regulations,[7] and the outbreak of the full-scale Russia-Ukraine conflict, which has disrupted travel between Moldova and Russia due to the absence of transit routes through Ukraine and direct flights. Many of those who previously worked in Russia now opt for short-term migration to countries such as Israel, Turkey, or Central European nations, including Poland.

Labour migration from Moldova has also been facilitated by Romania’s longstanding policy of granting (or, as the Romanian narrative describes it, restoring) citizenship to former Romanian citizens and their descendants who lost it involuntarily. This policy targets residents of territories that belonged to Romania before 1940, including Moldova (excluding Transnistria) as well as northern Bukovina and Budjak, now within Ukraine’s borders. Bucharest initiated this programme to address what it perceives as the ‘historical injustice’ of forcing residents of Bessarabia, which was annexed by the USSR, to renounce Romanian citizenship. As a result of this policy, implemented since the early 1990s, over one million Moldovans held Romanian passports by 2024.[8] Generally, these individuals do not migrate to Romania (according to the Moldovan Ministry of Foreign Affairs, only about 20,000 Moldovans reside there permanently) but instead use their EU citizenship to work or study throughout the European Union.

The socio-economic consequences of migration

Mass migration has a short-term positive impact on the standard of living for residents of Moldova. In 2023, remittances from labour migrants reached $2 billion, equivalent to approximately 12% of the country’s GDP. However, in the long term, this will severely affect Moldovan society, state administration structures, and the economy. Mass migration contributes to an increase in the number of so-called ‘migration orphans’ (children left in the care of extended family while their parents work abroad), weakens family bonds, and frequently leads to family breakdowns. Official data indicates that approximately 6% of all children under 17 are cared for by extended relatives or legal guardians due to parental migration.

In reality, this figure is likely much higher, potentially reaching 10%.[9] It is estimated that one in five children in Moldova grows up without parents or with only one parent. Although studies by UNICEF suggest that these children often have better access to quality healthcare and education, they are also more susceptible to behavioural problems and may encounter difficulties in social integration or adhering to societal norms due to insufficient attention from their caregivers. Labour migration is also a common cause of divorce, further compounding the difficulties faced by children. According to the National Bureau of Statistics of the Republic of Moldova, half of all marriages in the country have ended in divorce since the early 2000s. In 2022 alone, 18,200 marriages and 9,600 divorces were recorded.[10]

Chart 4. Dynamics of remittances from labour migrants in 1999–2023 and their share in GDP

Source: National Bank of Moldova and the International Monetary Fund.

Mass migration, combined with a worsening demographic crisis, is having a detrimental impact on Moldova’s economy, as it deprives the country of a key pillar of development. Furthermore, those leaving the country are often the best-educated and most experienced professionals, which leads to a significant brain drain. The labour force available on the market is steadily diminishing; by 2023, 20% of local businesses reported labour shortages.[11] The public sector and state administration also find it challenging to recruit young employees. This in turn affects the efficiency of government institutions and hinders the implementation of necessary reforms, including those linked to EU accession. Projections indicate that this situation will deteriorate in the coming years, adversely affecting Moldova’s economic growth indicators, significantly restricting foreign investment (which depends heavily on an affordable and skilled workforce), and potentially paralysing the state apparatus, which will struggle to function effectively without new personnel.

The pension system is becoming an additional challenge due to the rapidly ageing population. Over the past decade, the number of people aged 15 to 34 has decreased by 40%, while the proportion of those over 60 has risen significantly – from 9% in 1991 to 18% in 2019, and 25% in 2024. In 2015, there were 1.8 working individuals per pensioner, but by 2024 this ratio had dropped to just 1.3. There is little doubt that the ageing population will persist, posing an increasingly significant challenge to the state budget, which is already unable to provide adequate pensions. Despite substantial increases introduced by the government in 2024 (in some cases by as much as 100%), the average pension rose to approximately $200. However, this amount remains very low, considering that the subsistence minimum in 2023 was around $160.[12]

Labour migration is accompanied by the concerning phenomenon of brain drain, which affects both the economy and the state apparatus. The large-scale emigration of skilled professionals has diminished the possibilities of development in technological sectors and, more critically, has adversely affected certain public services, particularly healthcare. Over the past 25 years, the number of doctors employed in the healthcare system has decreased by 20%, despite a sharp rise in demand for their services due to the ageing population.[13] This outflow of specialists, combined with chronic underfunding of the healthcare sector and related challenges such as inadequate access to modern equipment and medication, has left Moldova grappling with issues such as low life expectancy and the spread of infectious diseases, including tuberculosis. In 2022, Moldova reported 80 cases of tuberculosis per 100,000 inhabitants, significantly more than other countries in the region (except Ukraine). For comparison, Romania recorded 52 cases, Poland 12, and Russia 39.[14]

The demographic situation in Transnistria

The separatist region of Transnistria, located on the left bank of the Dniester and beyond the de facto jurisdiction of Chișinău, experiences demographic trends and challenges similar to those of the rest of Moldova. According to its ‘official’ data, the region’s population has declined from 740,000 in 1990 (when it declared ‘independence’ from the Moldavian SSR) to approximately 455,000 at the beginning of 2024 – a 38.5% decrease.[15] However, these figures are likely inflated, as the actual population is estimated to be under 300,000, representing an almost 60% drop since 1990.[16] As in Moldova, the average age of Transnistria’s population is high, with pensioners comprising over 30% of its residents (95,500 in 2023).[17]

The population decline in Transnistria is primarily attributed to its challenging political and economic circumstances, which promote temporary or permanent emigration, mainly to Russia. According to partial data from Tiraspol, the average gross monthly salary in Transnistria during the first quarter of 2023 was approximately $360,[18] about 50% lower than in right-bank Moldova. This outmigration is exacerbated by high mortality rates and low fertility; in 2020 and 2021, deaths outnumbered births by a factor of two to three. There is little evidence to suggest that the situation in Transnistria will improve in the near future. Without political stabilisation – specifically reintegration with Moldova – reversing these negative demographic trends seems impossible.

The government’s efforts to address demographic challenges

Over the past three decades, successive Moldovan governments have been unable to cope with the deteriorating demographic crisis. Despite recent efforts to boost fertility – such as providing all parents, regardless of financial status, a one-time payment of approximately $1,115 upon the birth of a child and a monthly allowance of around $55 per child until the age of two,[19] – these measures have proven ineffective.

Efforts to reduce labour migration have also failed. Over the past four years, 184,000 people have left Moldova, with 75% of them aged between 18 and 29.[20] Furthermore, a 2024 survey revealed that nearly 25% of respondents aged 15 to 34 expressed an intention to emigrate.[21] The government has attempted to encourage emigrants to return or at least maintain ties with their homeland; to this end, a Diaspora Relations Bureau was established in 2017 to this effect. However, these initiatives have yielded no significant results. For instance, in 2022, the government introduced tax incentives, including exemptions from customs duties on cars, household appliances, and furniture, for citizens returning to settle permanently in Moldova. Nevertheless, this measure also proved ineffective. Emigrants frequently cite low wages offered by Moldovan employers and the low standard of public services as the primary reasons for staying abroad, rather than the costs associated with relocating back to Moldova.[22]

Owing to its very low wages compared to other countries in the region, Moldova is not an attractive destination for labour migrants from other parts of the world and cannot rely on immigration to offset labour shortages caused by emigration and negative population growth. In 2021, only about 22,000 foreigners lived in Moldova, with the vast majority (over 53%) not being labour migrants but citizens of Ukraine and Russia, often with family ties to Moldova.[23]

Efforts to encourage emigrants to return are further hampered by a weak sense of national identity and a lack of attachment to the Moldovan state. While Moldovan citizens share communal ties to their local origins (referred to as their ‘small homeland’), culture, and traditions, most do not feel compelled to make sacrifices for the country’s development. Instead, they prioritise securing their family’s wellbeing, which often leads to labour migration or relocating abroad with their relatives.

This fragile national identity has historical roots. Modern Moldova (excluding Transnistria) was part of Romania before World War II and, between the 14th and 19th centuries, belonged to the Principality of Moldavia – one of the two principalities that formed modern Romania in the mid-19th century. Moreover, Moldova, as an independent state is one of Europe’s youngest nations, having emerged for the first time in 1991. Consequently, roughly half of the population does not view Moldovan statehood as self-evident; at present, 35–40% of Moldovans support unification with Romania. Furthermore, as recently as 2017, 33% expressed support for Moldova joining the Russian Federation.[24]

Prospects

There is no indication that Moldova’s negative demographic trend will significantly slow in the coming years. World Bank estimates, based on UN methodology, predict that the country’s population will fall below 2 million by 2040 and drop to around 1.8 million by 2050. However, the situation may deteriorate further, as past projections have frequently been overly optimistic, with depopulation progressing more rapidly than expected. For example, in 2012, it was projected that Moldova’s population would decline to 2.5 million by 2050, but this level was reached 30 years earlier, in 2020.[25] Similarly, forecasts by the Centre for Demographic Research of the Academy of Sciences of Moldova missed the mark in 2016. According to their pessimistic scenario, Moldova’s current population of approximately 2.4 million was expected to be reached in 2028; however, this milestone was reached four years earlier.

Economic conditions will continue to drive migration and discourage citizens from having children. Although Moldova’s economy is growing, its pace lags behind other countries in the region (except Ukraine). Between 2000 and 2023, GDP per capita, measured in purchasing power parity, increased fifteenfold; however, it remains nearly three times lower than that of Romania and five times lower than that of the Czech Republic. Wages are also significantly below those in EU member states in the region. In the second quarter of 2024, the average gross salary in Moldova was approximately €730, compared to €1,680 in Romania and approximately €2,000 in Poland.

Even in the highly unlikely scenario of halting emigration, Moldova will continue to experience depopulation due to its low generational replacement rate. The disparity between births and deaths alone reduces the population by 5,000–10,000 people annually. Increasing the birth rate seems virtually impossible, as declining fertility is driven by the emigration of many young people of reproductive age and by economic factors. These challenges are further compounded by social and cultural changes in modern societies, which result in delays in motherhood or decisions to forgo having children altogether.

[1] The National Bureau of Statistics of the Republic of Moldova presents varying data on the population of Chișinău depending on the methodology used.

[2] In 1990, Gagauzia – a region in southern Moldova inhabited by the Gagauz minority – also declared independence from Moldova (then part of the USSR as a Soviet republic). However, in 1994, its self-proclaimed government reached an agreement with Chișinău, recognising its authority in exchange for the establishment of the Autonomous Territorial Unit of Gagauzia within the Moldovan state.

[3] For more details on the evolution of the Moldovan economy during the first 25 years of independence, see: K. Całus, The unfinished state. 25 years of independent Moldova, OSW, Warsaw 2016, osw.waw.pl.

[4] For comparison, GDP per capita in 2023 stood at $8,368 in Albania, $11,361 in Serbia, and $22,113 in Poland.

[5] N. Paholinițchii, ‘Câți cetățeni ai Moldovei sunt în străinătate? Diaspora moldovenească în UE, Rusia și în lumea întreagă’, NewsMaker, 7 July 2021, newsmaker.md.

[6] ‘Moldovenii au părăsit în masă Federația Rusă. În ultimii doi ani numărul lor a scăzut de 3,5 ori’, Moldstreet, 15 August 2022, mold-street.com.

[7] K. Chawryło, ‘Russia tightens up residence regulations for CIS citizens’, OSW, 15 January 2014, osw.waw.pl.

[8] ‘Maia Sandu: Un milion de cetățeni din R. Moldova au pașaport românesc. Acest lucru trebuie să scurteze calea noastră spre UE’, Digi24.ro, 7 May 2024.

[9] Many parents fail to report leaving their children in the care of family or friends, leading to distorted statistics. For more details see: E. Apostu, ‘Zeci de mii de copii din R. Moldova au părinții plecați în străinătate’, Europa Liberă, 27 July 2024, moldova.europalibera.org.

[10] M.E. Hîncu, ‘Numărul căsătoriilor și al divorțurilor, în scădere în Republica Moldova: Câte persoane și-au oficializat relația în 2022’, TV8.md, 4 July 2023.

[11] Prognoza Pieței Muncii Pentru Anul 2023 din Perspectiva Angajatorilor, National Agency for Employment of the Republic of Moldova, anofm.md.

[12] Data from the National Bureau of Statistics of the Republic of Moldova.

[13] I. Papuc, ‘Republica Moldova riscă să ajungă un deșert medical’, Veridica, 5 September 2024, veridica.md.

[14] ‘Incidence of tuberculosis (per 100,000 people) – Moldova, World, Albania, Poland, Russian Federation, Ukraine, Serbia, Romania’, World Bank, data.worldbank.org.

[15] Data from Transnistria’s ‘Ministry of Health.’

[16] See M. Necșuțu, ‘The war in Ukraine and the Republic of Moldova: all eyes on Transnistria’, Veridica, 28 February 2022, veridica.ro.

[17] ‘В Приднестровье пенсии получают почти 95,5 тысяч человек’, Новости Приднестровья, 31 March 2024, novostipmr.com.

[18] И. Шлаева, ‘Средние зарплаты в Приднестровье в первом квартале 2023 года’, LikTV - Рыбницкое интернет-телевидение, 24 June 2023, liktv.org.

[19] ‘Ce reprezintă programul „Familia”?’, Ministry of Labour and Social Protection of the Republic of Moldova, January 2024, social.gov.md.

[20] ‘Tot mai mulți tineri pleacă din Republica Moldova’, TVR, 14 August 2024, tvr.ro.

[21] A. Popescu, ‘Republica Moldova rămâne fără tineri: Unul din patru și-a anunțat intenția de emigra’, Stiripesurse, 17 September 2024, stiripesurse.md.

[22] ‘Scutiri de taxe pentru bunurile aduse de moldovenii din diaspora care revin definitiv acasă’, Europa Liberă, 19 July 2022, moldova.europalibera.org.

[23] ‘Profilul migrațional extins al Republicii Moldova 2017–2021’, General Inspectorate for Migration, igm.gov.md.

[24] ‘Majoritatea moldovenilor ar vota la un referendum pentru unirea țării cu România sau Federația Rusă’, Europa Liberă, 14 December 2017, moldova.europalibera.org.

[25] ‘Elderly persons will represent one third of Moldova’s population towards 2050’, IPN Press Agency, 26 January 2012, ipn.md.