Regional elites in wartime Russia

The full-scale invasion of Ukraine has complicated the situation for the leadership of Russia’s regions. On the one hand, it has reinforced existing trends, including the Kremlin’s conservative personnel policy, which is characterised by limited reshuffles. On the other hand, it has increased the burden of war-related tasks and subjected regional elites to Western sanctions. Their chances of advancing to the federal level have diminished due to competition from participants in the invasion, who are being co-opted by Putin’s regime. This competition for positions and influence is partly internal. Despite official rhetoric, the expanding group of war veterans promoted to official roles remains dominated by members of the existing elite, for whom participation in the war has served as a career springboard. While this growing conflict is useful to Vladimir Putin as a disciplinary tool, it poses long-term dilemmas. Limited turnover risks the resurgence of local clan-based structures and the strengthening of cross-regional factions. As a result, the Kremlin will need to devise a solution that balances the interests of both the established regional elites and the invasion participants favoured by the system.

Stagnation in personnel turnover and declining opportunities for regional elites

The invasion of Ukraine has not fundamentally altered Putin’s system of regional control. The Kremlin has expanded a mechanism first tested during the COVID-19 pandemic, enabling it to maintain strict oversight of regional elites while shifting political and social responsibility for policy implementation onto them.[1] As the war has progressed, Moscow’s expectations – particularly of regional governors – have increased. Although most are formally elected through popular vote, they effectively serve as viceroys of the central federal leadership.[2]

The Kremlin’s demands on regional leaders are contradictory. On the one hand, they are expected to contribute to the war effort, whether by recruiting soldiers or participating in the reconstruction of occupied territories. They must also respond efficiently to crises. On the other hand, they are required to achieve development goals and minimise the war’s impact on the population. At the same time, Moscow is at least partially reducing its reliance on regional authorities to secure the desired election outcomes. Instead, it is using tools such as online remote voting, which is both the simplest and the hardest – to detect method of electoral fraud.

The criteria guiding the Kremlin’s personnel decisions remain unclear, suggesting an absence of a coherent selection algorithm. Official requirements have been introduced in the form of extensive performance indicators for governors, reflecting the state’s current priorities, such as increasing birth rates in the regions.[3] However, these indicators serve more as political guidelines, pointing to general directions rather than specific targets for regional leaders.[4] Moscow’s staffing decisions are, to some extent, detached from these metrics. While a governor’s performance may be used to justify their promotion or dismissal, it is rarely the decisive factor.

Beyond its discretionary nature, the Kremlin’s personnel policy has also been notably conservative in recent years. Limited turnover[5] and the small number of prestigious central government positions have significantly reduced the prospects for regional leaders, many of whom view their roles as stepping stones to the federal level. Although 2024 saw more changes in the gubernatorial corps than in the previous two years, many of these were linked to the formation of a new government rather than a shift in policy.

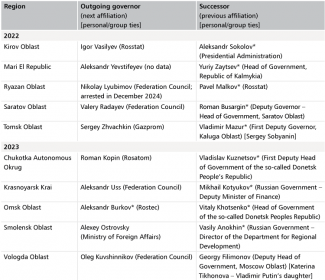

Table 1. Gubernatorial reshuffles from 2022 to 2025

Source: own analysis.

Among the gubernatorial reshuffles between 2022 and 2024, only two cases may be considered genuine demotions. The first is Alexey Smirnov, who was removed as head of Kursk Oblast after just six months, partly due to his failure to communicate effectively with residents during Ukraine’s military operations in the region.[6] The second is Andrey Turchak, a prominent figure within Russia’s elite and Secretary of the ruling United Russia party’s General Council. His reassignment to the geographically remote and underdeveloped Altai Republic suggests he has fallen out of favour with the Kremlin.

Despite political turbulence, the heads of Bashkortostan,[7] and Orenburg Oblast,[8] have retained their positions. This is likely due to the Kremlin’s reluctance to enact personnel changes under public pressure.

Graduating from the so-called Governors’ School remains a significant advantage for those seeking regional leadership positions. This specialised technocratic management programme is run by the Russian Presidential Academy of National Economy and Public Administration (RANEPA).[9] However, experience in administering occupied Ukrainian territories appears to be less advantageous. Vitaly Khotsenko and Vladislav Kuznetsov, both of whom held positions in these regions and completed Governors’ School, were appointed to relatively low-profile regions. Meanwhile, Maria Kostyuk, the current head of her native Jewish Autonomous Oblast, previously worked for the state-run Defenders of the Fatherland Foundation, which provides support to Russian invasion veterans. Her son was killed in Ukraine.

For outgoing governors, a common next step at the federal level is the Federation Council, partly due to the immunity it provides. For example, shortly after Vasily Golubev moved to the Senate, arrests began among his former associates in Rostov Oblast. More recently, law enforcement agencies have also shown interest in securing Federation Council seats. In July 2024, amendments were passed removing the residency requirement (previously five consecutive years or a total of 20), which applied, among others, to senior security officials seeking a mandate.[10]

Limited turnover in regional leadership raises the risk of a resurgence of local clan-based structures,[11] which Moscow has systematically dismantled as part of its centralisation policy. Kremlin-appointed governors may become entrenched within regional political and business elites. Meanwhile, the prospects for these local elites to advance are further diminished by the fact that, in most cases, the governorship has been merged with the role of regional government head and local United Russia branch leader. For now, however, this remains merely a potential problem.

In recent years, supra-regional connections have become more visible. Informal interest groups centred around specific individuals or entities are playing an increasingly prominent role in regional politics. War-related defence spending has benefited figures linked to Sergey Chemezov, head of the state-owned corporation Rostec, who has ‘representatives’ in Kaliningrad and Rostov oblasts, as well as within the Russian government. His influence extends to the circles around Viktor Zolotov, commander of the National Guard of Russia (Rosgvardiya), whose former adviser now governs Kursk Oblast.

Moscow Mayor Sergey Sobyanin’s faction also retains a strong position. His ally, Vladimir Yakushev, who previously served as the presidential envoy to the Ural Federal District, where most governors are affiliated with this camp, has replaced Turchak as Secretary of United Russia’s General Council. In contrast, the faction of former Defence Minister Sergey Shoigu appears to be in retreat. This is reflected in pressure from law enforcement agencies on the entourage of his ally, Moscow Oblast Governor Andrey Vorobyov.[12] Additionally, Ruslan Tsalikov, Shoigu’s former deputy and once considered the frontrunner for a Federation Council seat representing Tuva, was ultimately not appointed.

It remains unclear why Putin is allowing the growing activity of supra-regional interest groups. The Kremlin has shown surprising restraint, for example, in the conflict surrounding Wildberries, Russia’s largest e-commerce platform.[13] The opposing sides in the dispute sought protection from different power brokers – Dagestan’s Federation Council senator, Suleyman Kerimov, and Chechen leader Ramzan Kadyrov, whose faction has also been seizing economic assets in occupied Ukrainian territories. Despite Kadyrov’s intervention – which disrupted a transaction overseen by the Presidential Administration, triggering a shootout in central Moscow, escalated tensions between Chechnya and Ingushetia, and prompted threats against Kerimov and lawmakers from Dagestan and Ingushetia – Putin remained passive. Regardless of the reasons for his inaction, prolonged reluctance to act as an arbiter could undermine the security of regional elites who lack high-level protection. Their ability to defend themselves against supra-regional interest groups and law enforcement agencies would be further weakened.

The invasion has also exacerbated several other challenges for regional elites. Nearly all governors have been placed on international sanctions lists, while officials in many federal entities face domestic restrictions on foreign travel. At the same time, the war has set a precedent for evading criminal liability – with at least several dozen regional officials reportedly sent to the front to avoid prosecution.[14] Meanwhile, towards the end of 2024, the central government resumed efforts to implement a nationwide reform of the local government system, including plans to eliminate its lower tier. Elites, particularly in Tatarstan, succeeded in softening some of the reform’s provisions through resistance.[15] However, this victory may prove short-lived.

With limited opportunities for promotion and shrinking avenues for engagement with federal authorities, regional elites face an additional challenge: increasing competition from participants in Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

The emergence of ‘new’ elites

The Kremlin launched a coordinated effort to co-opt participants in Russia’s invasion of Ukraine into the elite at the start of 2024. On 29 February, in his address to the Federal Assembly, Putin criticised the existing elite – particularly those who rose to prominence in the 1990s – and identified participants in the so-called special military operation (Russian специальная военная операция, SVO) as a group that should hold senior positions in government, public administration, and business. He also announced a dedicated management and leadership programme for them, titled ‘Time of Heroes’, which was launched in March. The programme is run by RANEPA and is unofficially coordinated by the Presidential Administration. Participants must have a higher education and experience in managing people, which favours former (or active) officials. Of the more than 40,000 applicants, 83 were selected: 65 career military personnel or individuals with a background in the Ministry of Defence; 14 volunteers or mobilised soldiers; three Rosgvardiya officers; one Interior Ministry officer; and four military doctors. Some of the participants have been accused or suspected by Ukraine of committing war crimes.[16] An additional recruitment round attracted a further 21,500 applicants.

From the Putin regime’s perspective, integrating invasion participants into the elite is both a logical consequence of the militarisation of public life and a move to ensure future social stability – particularly given the potential return of hundreds of thousands of soldiers who may struggle to reintegrate. It also serves as a tool to discipline the existing establishment. However, despite the authorities’ rhetoric, the main beneficiaries of this process are members of the current elite, who have used their involvement in the war to accelerate their careers. In contrast, the inclusion of actual veterans into the elite continues to face resistance from regional bureaucracies.

Positions granted to participants of the so-called special military operation – whether graduates of Time of Heroes or others – have largely been at the regional or local level. While often prestigious, these roles typically do not come with real power or access to significant resources. This is likely due to both the veterans’ insufficient qualifications and obstruction by existing regional elites, who are reluctant to expand their ranks to include outsiders. This reluctance is particularly evident in the psychological divide between new and old elites, as well as between war participants and civilians. Under pressure to comply with Moscow’s directives to increase veteran representation in public administration, regional elites have sought to meet these requirements at minimal cost by assigning veterans to largely symbolic positions.

Resistance from regional and local elites was particularly evident during the September 2024 elections, in which 35,000 seats at various levels were contested. Despite United Russia granting SVO participants a primary election advantage – an extra quarter of the votes – only 380 candidates with frontline experience were put forward, accounting for less than 1% of the total number (compared with around 100 the previous year). Of these, 34 secured seats in regional parliaments, 46 were elected to municipal councils in regional capitals, and 233 were elected to positions in other local government bodies. The three officially sanctioned opposition parties – the Communist Party of the Russian Federation, the Liberal Democratic Party of Russia, and A Just Russia – For Truth – fielded only 115 candidates with combat experience, 18 of whom were elected. This highlights that the issue is of marginal importance to the political elite.

Veterans running for regional legislatures – strongholds of local business elites – faced significant resistance. They suffered a particularly decisive defeat in Moscow, where none of the 15 SVO-experienced candidates were successful in United Russia’s primaries. In pre-elections for regional parliaments, preference was given to veterans with prior political involvement or those featured prominently in propaganda. In some cases, SVO participants encountered administrative pressure and electoral fraud aimed at their disadvantage.[17]

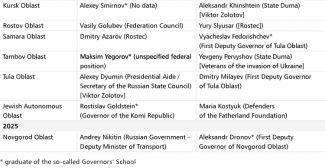

At the same time, since September 2024, the number of veterans in high-profile regional political positions has noticeably increased. However, most of those appointed were already part of the elite prior to the war, holding senior public administration roles (some directly linked to the officials who appointed them).

This trend reflects the emergence of ‘nomenklatura’ veterans – distinct from frontline veterans – who volunteered for the war primarily to accelerate their careers. Over nearly three years, Novaya Gazeta. Europe identified 70 such cases.[18] Most served under preferential conditions in special volunteer units – such as the Kaskad brigade or Novosibirsk’s Vega battalion – without direct combat experience. They kept their mandates and positions, continued political activity, and even travelled abroad while officially deployed. Some, however, were killed in action, including Sergey Yefremov, Deputy Governor of Primorsky Krai. Half of these veterans spent six months or less in the war zone. By October 2024, the governor of Belgorod Oblast even complained about a shortage of officials due to their departure for the ‘front’, as three of his deputies had enlisted in a regional volunteer unit.

Table 2. Profiles of selected invasion veterans holding senior positions in regional politics

Source: own analysis.

The significance of these appointments should not be overstated. Artyom Zhoga – who was used in propaganda to publicly ‘ask’ Putin to run in the 2024 presidential ‘election’ – has been assigned to a district where Sergey Sobyanin’s faction holds significant influence, likely limiting his ability to operate. Meanwhile, Tambov Oblast, now led by Yevgeny Pervyshov, is of little political or economic importance. Its population is smaller than that of Krasnodar, the city he previously governed. Veterans’ appointments as deputy governors or senators can be seen as gestures by the governors who nominated them, aimed at boosting their standing with the Kremlin – particularly in the case of Turchak.

Senate seats are likely to become another battleground between the new ‘wartime’ elites and the old ‘civilian’ establishment. The Federation Council has traditionally been viewed as a source of sinecures for former governors. Competition may intensify further, given the growing interest of law enforcement officials in securing positions in the upper house of parliament. Among the veteran senators, one had already held a seat in the Federation Council, while the others reportedly face social ostracism within the chamber.[19]

The Kremlin is intensifying efforts to co-opt war participants into the elite. The governor performance indicators, updated in November 2024 include veterans’ satisfaction with medical rehabilitation, professional retraining, and employment opportunities. In January, Yakushev announced that veterans – particularly those with experience in regional legislatures, again favouring ‘nomenklatura’ veterans – would be placed on United Russia’s candidate lists for the 2026 State Duma elections. Veterans are also being promoted through the Leaders of Russia management competition.

Some regional leaders, eager to gain favour with Moscow, are actively supporting this policy. In December, Putin called for the creation of regional equivalents of Time of Heroes, a step some regions had already taken. These initiatives have now been launched in nearly all federal subjects.[20] Meanwhile, the governor of Samara Oblast announced that graduates of the local programme would oversee the work of the regional administration and municipal governments – creating yet another potential source of conflict.

The Kremlin’s staffing dilemma

Despite stagnation in personnel turnover, the Kremlin is actively working to co-opt war participants into the elite. Given the limited opportunities for advancement, competition for positions and resources – whether administrative, financial, or otherwise – is likely to intensify. This is likely to increase in direct proportion to Moscow’s pressure to integrate veterans into the power structure, particularly at the regional level. Tensions could peak once military operations end or are frozen, as the mass return of SVO participants from the front will compel the authorities to allocate more positions to them.

However, these tensions are unlikely to become openly confrontational. They will likely manifest through bureaucratic obstruction of the Kremlin’s directives or isolated conflicts, potentially involving interventions by law enforcement agencies. A notable example is the case in Sosnovka, Kirov Oblast, where a veteran was elected mayor with the Governor’s support. He soon clashed with local elites, who attempted to remove him by having the regional military commissioner issue an order for his return to the front.[21]

The Kremlin’s co-optation policy is likely to continue favouring ‘nomenklatura’ veterans. Given their position within the power structure and prior experience, they have a clear advantage over ‘frontline’ veterans – whether career military personnel or mobilised soldiers. The latter group has limited influence and will primarily be assigned to secondary roles in public administration, state-controlled corporations, and similar institutions. At the same time, they will remain easy targets for bureaucratic elites unwilling to share power. Resistance from the current establishment to integrating SVO participants may therefore focus on restricting the advancement of ‘frontline’ veterans.

It remains an open question to what extent the Kremlin is willing to replace the existing elite with veterans. However, the conflict between these factions serves as a useful disciplinary tool for Putin, at least in the short term. While there are frequent declarations about turning SVO participants into a ‘new elite’, numerous obstacles could hinder this process. Beyond bureaucratic resistance, Moscow must also consider public dissatisfaction. Hostility toward veterans could grow due to their privileges and the social destabilisation linked to demobilisation. Concerns also persist regarding their qualifications and suitability for civilian administration. Additionally, their collective ethos and group solidarity may pose a challenge for a system that is inherently wary of horizontal networks and independent power structures.

The Kremlin must also maintain its ability to offer regional elites opportunities for advancement. Between 2027 and 2029, the terms of approximately 60 regional leaders will expire under existing regulations, with two-thirds of them serving at least their second consecutive term.[22] This will present Moscow with a staffing dilemma. A decision to carry out appointments on a large scale – potentially involving veterans – would require securing sufficiently prestigious positions for outgoing governors. On the other hand, retaining the current leaders for longer risks a resurgence of local clan-based politics and the strengthening of supra-regional factions, in which governors will seek external patronage.

Balancing the interests of systemically favoured war participants and frustrated regional elites, who face limited prospects for promotion, will therefore be a key challenge for the Kremlin.

[1] A. Tóth-Czifra, ‘On 2025 in Russian politics’, No Yardstick, 15 January 2025, noyardstick.com.

[2] M. Bartosiewicz, ‘A tactical pause. The Kremlin's regional policy in the shadow of the war’, OSW Commentary, no. 543, 6 October 2023, osw.waw.pl.

[3] А. Винокуров, ‘Приказано высчитать’, Коммерсантъ, 28 November 2024, kommersant.ru.

[4] A. Toth-Czifra, ‘How to signal loyalty: the case of Russian governors’, Riddle, 16 December 2024, ridl.io.

[5] While between 2016 and 2018 an average of 17 governors were replaced annually, this figure fell to 10 between 2019 and 2021, and to 8 between 2022 and 2024.

[6] ‘«У нас тут настоящий управленческий кризис»: Хинштейна отправили спасать Курскую область после отставки губернатора Смирнова’, Вёрстка, 6 December 2024, verstka.media.

[7] M. Bartosiewicz, ‘More protests in Bashkortostan’, OSW, 23 January 2024, osw.waw.pl.

[8] Idem, ‘Seria powodzi w Rosji: spóźniona reakcja władz’, OSW, 16 April 2024, osw.waw.pl.

[9] The executive talent development programme was launched in 2017 under the supervision of Sergey Kiriyenko, First Deputy Chief of the Presidential Administration and responsible for domestic policy. By mid-2024, more than 450 individuals had taken part in the programme, nearly 60 of whom had been appointed as governors.

[11] А. Pertsev, ‘Russia's Political Sclerosis Is Creating Regional Fiefdoms’, Carnegie Politika, 2 July 2024, carnegieendowment.org.

[12] Т. Юрасова, ‘Зачистка клана’, Новая газета, 15 January 2025, novayagazeta.ru.

[13] For more information on the conflict, see A. Kazantsev-Vaisman, ‘Rivalry Over Wildberries as an Ethno-Political Conflict Within the Russian Elite’, The Begin-Sadat Center for Strategic Studies, 12 August 2024, besacenter.org.

[14] С. Горяшко, ‘«Сижу в СИЗО, а должен воевать под Курском». Как ФСБ (не) отпускает коррупционеров из тюрьмы на войну’, BBC News Русская служба, 25 February 2025, bbc.com.

[15] K. Веретенникова, А. Прах, ‘Поправляй и властвуй’, Коммерсантъ, 20 January 2025, kommersant.ru.

[16] М. Ливадина, ‘«Люди с правильной жизненной позицией»’, Новая газета. Европа, 21 August 2024, novayagazeta.eu.

[17] ‘«Что-то где-то подкручивали!»: участники войны в Украине пошли на выборы в РФ и провалились’, Вёрстка, 29 May 2024, verstka.media.

[19] ‘«Он дуб-дубом»: как участникам войны в Украине не удаётся устроиться во власти’, Вёрстка, 11 October 2024, verstka.media.

[20] Б. Иванова, ‘Резерв народного главнокомандования’, Коммерсантъ, 10 March 2025, kommersant.ru.

[21] А. Орлов, ‘Фронтовик-мэр стал проклятием для чиновников: его решили отправить обратно "за ленточку"’, Дзен, 23 December 2024, dzen.ru.

[22] А. Kynev, ‘REGIONAL ELITES IN THE ERA OF THE 'SPECIAL MILITARY OPERATION': EVOLUTION, CURRENT STATE AND SCENARIOS’, RE: RUSSIA, 17 December 2024, re-russia.net.